Himalayan Blackberry (Rubus Discolor)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Relatives of Temperate Fruits) of the Book Series, "Wild Crop Relatives: Genetic, Genomic and Breeding Resources Ed C

Volume 6 (Relatives of Temperate Fruits) of the book series, "Wild Crop Relatives: Genetic, Genomic and Breeding Resources ed C. Kole 2011 p179-197 9 Rubus J. Graham* and M. Woodhead Scottish Crop Research Institute, Dundee, DD2 5DA, UK *Corresponding author: [email protected] Abstract The Rosaceae family consists of around 3, 000 species of which 500 belong to the genus Rubus. Ploidy levels range from diploid to dodecaploid with a genomic number of 7, and members can be difficult to classify into distinct species due to hybridization and apomixes. Species are distributed widely across Asia, Europe, North and South America with the center of diversity now considered to be in China, where there are 250-700 species of Rubus depending on the taxonomists. Rubus species are an important horticultural source of income and labor being produced for the fresh and processing markets for their health benefits. Blackberries and raspberries have a relatively short history of less than a century as cultivated crops that have been enhanced through plant breeding and they are only a few generations removed from their wild progenitor species. Rubus sp. are typically found as early colonizers of disturbed sites such as pastures, along forest edges, in forest clearings and along roadsides. Blackberries are typically much more tolerant of drought, flooding and high temperatures, while red raspberries are more tolerant of cold winters. Additionally, they exhibit vigorous vegetative reproduction by either tip layering or root suckering, permitting Rubus genotypes to cover large areas. The attractiveness of the fruits to frugivores, especially birds, means that seed dispersal can be widespread with the result that Rubus genotypes can very easily be spread to new sites and are very effective, high-speed invaders. -

Analysis of Flavonoids in Rubus Erythrocladus and Morus Nigra Leaves Extracts by Liquid Chromatography and Capillary Electrophor

Revista Brasileira de Farmacognosia 25 (2015) 219–227 www.sbfgnosia.org.br/revista Original Article Analysis of flavonoids in Rubus erythrocladus and Morus nigra leaves extracts by liquid chromatography and capillary electrophoresis a a b c Luciana R. Tallini , Graziele P.R. Pedrazza , Sérgio A. de L. Bordignon , Ana C.O. Costa , d e a,∗ Martin Steppe , Alexandre Fuentefria , José A.S. Zuanazzi a Departamento de Produc¸ ão de Matéria Prima, Faculdade de Farmácia, Universidade Federal do Rio Grande do Sul, Porto Alegre, RS, Brazil b Centro Universitário La Salle, Canoas, RS, Brazil c Departamento de Ciência e Tecnologia de Alimentos, Universidade Federal de Santa Catarina, Florianópolis, SC, Brazil d Departamento de Produc¸ ão e Controle de Medicamentos, Faculdade de Farmácia, Universidade Federal do Rio Grande do Sul, Porto Alegre, RS, Brazil e Departamento de Análises, Faculdade de Farmácia, Universidade Federal do Rio Grande do Sul, Porto Alegre, RS, Brazil a a b s t r a c t r t i c l e i n f o Article history: This study uses high performance liquid chromatography and capillary electrophoresis as analytical tools Received 15 January 2015 to evaluate flavonoids in hydrolyzed leaves extracts of Rubus erythrocladus Mart., Rosaceae, and Morus Accepted 30 April 2015 nigra L., Moraceae. For phytochemical analysis, the extracts were prepared by acid hydrolysis and ultra- Available online 17 June 2015 sonic bath and analyzed by high performance liquid chromatography using an ultraviolet detector and by capillary electrophoresis equipped with a diode-array detector. Quercetin and kaempferol were iden- Keywords: tified in these extracts. The analytical methods developed were validated and applied. -

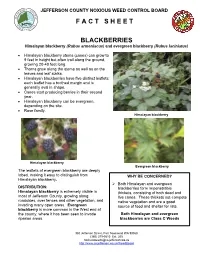

F a C T S H E E T Blackberries

JEFFERSON COUNTY NOXIOUS WEED CONTROL BOARD F A C T S H E E T BLACKBERRIES Himalayan blackberry (Rubus armeniacus) and evergreen blackberry (Rubus laciniatus) Himalayan blackberry stems (canes) can grow to 9 feet in height but often trail along the ground, growing 20-40 feet long. Thorns grow along the stems as well as on the leaves and leaf stalks. Himalayan blackberries have five distinct leaflets; each leaflet has a toothed margin and is generally oval in shape. Canes start producing berries in their second year. Himalayan blackberry can be evergreen, depending on the site. Rose family. Himalayan blackberry Himalayan blackberry Evergreen blackberry The leaflets of evergreen blackberry are deeply lobed, making it easy to distinguish from WHY BE CONCERNED? Himalayan blackberry. Both Himalayan and evergreen DISTRIBUTION: blackberries form impenetrable Himalayan blackberry is extremely visible in thickets, consisting of both dead and most of Jefferson County, growing along live canes. These thickets out-compete roadsides, over fences and other vegetation, and native vegetation and are a good invading many open areas. Evergreen source of food and shelter for rats. blackberry is more common in the West end of the county, where it has been seen to invade Both Himalayan and evergreen riparian areas. blackberries are Class C Weeds 380 Jefferson Street, Port Townsend WA 98368 (360) 379-5610 Ext. 205 [email protected] http://www.co.jefferson.wa.us/WeedBoard ECOLOGY: . Seeds can be spread by birds, humans and other mammals. The canes often cascade outwards, forming mounds, and can root at the tip when they hit the ground, expanding the infestation . -

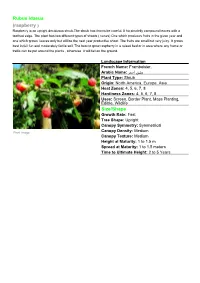

Rubus Idaeus (Raspberry ) Size/Shape

Rubus idaeus (raspberry ) Raspberry is an upright deciduous shrub.The shrub has thorns be careful. It ha pinatelly compound leaves with a toothed edge. The plant has two different types of shoots ( canes) One which produces fruits in the given year and one which grows leaves only but will be the next year productive shoot. The fruits are small but very juicy. It grows best in full fun and moderately fertile soil. The best to grow raspberry in a raised bed or in area where any frame or trellis can be put around the plants , otherwise it will fall on the ground. Landscape Information French Name: Framboisier, ﻋﻠﻴﻖ ﺃﺣﻤﺮ :Arabic Name Plant Type: Shrub Origin: North America, Europe, Asia Heat Zones: 4, 5, 6, 7, 8 Hardiness Zones: 4, 5, 6, 7, 8 Uses: Screen, Border Plant, Mass Planting, Edible, Wildlife Size/Shape Growth Rate: Fast Tree Shape: Upright Canopy Symmetry: Symmetrical Plant Image Canopy Density: Medium Canopy Texture: Medium Height at Maturity: 1 to 1.5 m Spread at Maturity: 1 to 1.5 meters Time to Ultimate Height: 2 to 5 Years Rubus idaeus (raspberry ) Botanical Description Foliage Leaf Arrangement: Alternate Leaf Venation: Pinnate Leaf Persistance: Deciduous Leaf Type: Odd Pinnately compund Leaf Blade: 5 - 10 cm Leaf Shape: Ovate Leaf Margins: Double Serrate Leaf Textures: Rough Leaf Scent: No Fragance Color(growing season): Green Flower Image Color(changing season): Brown Flower Flower Showiness: True Flower Size Range: 1.5 - 3 Flower Type: Raceme Flower Sexuality: Monoecious (Bisexual) Flower Scent: No Fragance Flower Color: -

2013 BGSS Abstract Book UPDATED

th 26 Annual Biology Graduate Student Symposium Program and Abstracts Oregon State University Mark O. Hatfield Marine Science Center Newport, Oregon March 2nd, 2013 Table of Contents Page Message from 2013 Organizing Committee 1 Acknowledgements 2 General Information 2 Schedule of Talks 3 Keynote Speaker 4 Oral Presentation Abstracts 4 Poster Presentation Abstracts 10 Map of the Hatfield Marine Science Center (HMSC) 13 Directions to the Rental House from HMSC 14 Message from the 2013 Organizing Committee th Welcome to the 26 Annual Biology Graduate Student Symposium! This conference, organized by and for graduate students, brings together students from all the life science departments at Oregon State University. It is a forum to share research with our peers and to facilitate a better appreciation of the breadth of biological investigation that occurs at our university. This gathering is an opportunity to broaden our outlook on the study of biology; to discuss graduate life and current events; and encourage interactions between future researchers in the various life sciences. We hope you have a productive conference and that you will bring away a positive experience to share with other students. 2013 Organizing Committee Casey Benkwitt Elizabeth Cerny-Chipman Cammie Crowder Emily Hartfield Tye Kindinger Sheila Kitchen Dani Long Trang Nguyen Jessie Reimer Chenchen Shen Hannah Tavalire 1 Acknowledgements We gratefully acknowledge the support of the following sponsors: OSU Departments: Department of Fisheries and Wildlife Department of Zoology College of Earth, Ocean, and Atmospheric Sciences College of Education College of Science Graduate School Venue: Hatfield Marine Science Center of Oregon State University Refreshments and Food: First Alternative Co-Op Fred Meyer Rogue Brewery Safeway General Information Presentations: The symposium will take place in the Auditorium at the Hatfield Marine Science Center (HMSC) (map – p. -

Here Are Over 2,100 Native Rare Plant Finds at 11 Bear Run Nature Plant Species in Pennsylvania, and About Reserve 800 Species Are of Conservation Concern

Pennsylvania Natural Heritage Program informationinformation forfor thethe conservationconservation ofof biodiversitybiodiversity WILD HERITAGE NEWS Summer 2018 Tough Nuts to Crack Inside This Issue Zeroing in on Some of Our Most Mysterious Plant Species by Tough Nuts to Crack 1 Jessica McPherson Emerging Invasive 6 Scientific understanding of our native Cleveland Museum of Natural History. Plant Threats biodiversity is a constant work in progress. The stories of some of these species EYE Con Summer 8 We continue to uncover the intricacies of illustrate the interesting complexities of Camp our native plant species habitat our native diversity, some trends in Spotted Turtle 8 requirements, biological needs, and conservation, and some of the data gaps Conservation ecological interrelationships such as animal that often challenge our ability to assess State Park Vernal Pool 9 pollinators and seed dispersers. To the conservation needs of plant species. Surveys determine the conservation needs of our native species, the Natural Heritage Netted Chain Fern New Cooperative Weed 9 Program synthesizes the best available The netted chain fern (Woodwardia Management Area science on what we know a species needs areolata) was previously known almost Tick Borne Disease 10 to survive with population data and information exclusively from the coastal plain in Collaboration on any threats it faces. For plants, the Pennsylvania, but new field work suggests Indian Creek Caverns 11 sheer numbers of species pose a significant challenge; there are over 2,100 native Rare Plant Finds at 11 Bear Run Nature plant species in Pennsylvania, and about Reserve 800 species are of conservation concern. Mudpuppy Project 12 The Plant Status Update Project Spring Insect Survey 13 completed in 2016, was a focused Photo Highlights investigation of 56 plant species that DCNR determined lacked sufficient data to evaluate the appropriate conservation Photo Banner: status. -

Identification of Bioactive Phytochemicals in Mulberries

H OH metabolites OH Article Identification of Bioactive Phytochemicals in Mulberries Gilda D’Urso 1 , Jurriaan J. Mes 2, Paola Montoro 1 , Robert D. Hall 3,4 and Ric C.H. de Vos 3,* 1 Department of Pharmacy, University of Salerno, 84084 Fisciano SA, Italy; [email protected] (G.D.); [email protected] (P.M.) 2 Business Unit Fresh Food and Chains, Wageningen Food & Biobased Research, Wageningen University and Research, 6708 WG Wageningen, The Netherlands; [email protected] 3 Business Unit Bioscience, Wageningen Plant Research, Wageningen University and Research, 6708 PB Wageningen, The Netherlands; [email protected] 4 Laboratory of Plant Physiology, Wageningen University and Research, 6708 PB Wageningen, The Netherlands * Correspondence: [email protected]; Tel.: +31-317480841 Received: 29 November 2019; Accepted: 18 December 2019; Published: 20 December 2019 Abstract: Mulberries are consumed either freshly or as processed fruits and are traditionally used to tackle several diseases, especially type II diabetes. Here, we investigated the metabolite compositions of ripe fruits of both white (Morus alba) and black (Morus nigra) mulberries, using reversed-phase HPLC coupled to high resolution mass spectrometry (LC-MS), and related these to their in vitro antioxidant and α-glucosidase inhibitory activities. Based on accurate masses, fragmentation data, UV/Vis light absorbance spectra and retention times, 35 metabolites, mainly comprising phenolic compounds and amino sugar acids, were identified. While the antioxidant activity was highest in M. nigra, the α-glucosidase inhibitory activities were similar between species. Both bioactivities were mostly resistant to in vitro gastrointestinal digestion. To identify the bioactive compounds, we combined LC-MS with 96-well-format fractionation followed by testing the individual fractions for α-glucosidase inhibition, while compounds responsible for the antioxidant activity were identified using HPLC with an online antioxidant detection system. -

Plant Collecting Expedition for Berry Crop Species Through Southeastern

Plant Collecting Expedition for Berry Crop Species through Southeastern and Midwestern United States June and July 2007 Glassy Mountain, South Carolina Participants: Kim E. Hummer, Research Leader, Curator, USDA ARS NCGR 33447 Peoria Road, Corvallis, Oregon 97333-2521 phone 541.738.4201 [email protected] Chad E. Finn, Research Geneticist, USDA ARS HCRL, 3420 NW Orchard Ave., Corvallis, Oregon 97330 phone 541.738.4037 [email protected] Michael Dossett Graduate Student, Oregon State University, Department of Horticulture, Corvallis, OR 97330 phone 541.738.4038 [email protected] Plant Collecting Expedition for Berry Crops through the Southeastern and Midwestern United States, June and July 2007 Table of Contents Table of Contents.................................................................................................................... 2 Acknowledgements:................................................................................................................ 3 Executive Summary................................................................................................................ 4 Part I – Southeastern United States ...................................................................................... 5 Summary.............................................................................................................................. 5 Travelog May-June 2007.................................................................................................... 6 Conclusions for part 1 ..................................................................................................... -

Growing Cane Berries in the Sacramento Region

Cooperative Extension-Sacramento County 4145 Branch Center Road, Sacramento, CA 95827-3823 (916) 875-6913 Office • (916) 875-6233 Fax Website: sacmg.ucanr.edu Environmental Horticulture Notes EHN 86 GROWING CANE BERRIES IN THE SACRAMENTO REGION With good preparation and proper care, most cane berries (blackberries and raspberries) can be grown in the Sacramento area. Cane berries are very manageable if they are trellised and pruned correctly, and if their roots are contained when necessary, such as with red raspberries. This paper focuses on cane berries in the garden, but most of the topics are relevant to commercial production as well. See EHN 88 for information on blueberries. SPECIES AND VARIETIES BLACKBERRIES, BOYSENBERRIES AND RELATED BERRIES Several berry types, both thorny and thornless, are often classified as blackberries and are sometimes called dewberries. The main types are western trailing types (Rubus ursinus), which are discussed below, and erect and semi-erect cultivars (no trellis required), which are being developed mainly for cold climates. Most trailing varieties root at the tips of shoots if they come in contact with the soil. BLACKBERRIES: One of the oldest and most popular varieties is ‘Ollalie’, which is actually a cross between blackberry, loganberry, and youngberry. It is large and glossy black at maturity and is slightly longer and more slender than the boysenberry. ‘Thornless Black Satin’ has a heavy crop of large, elongated dark berries that are good for fresh eating or cooking. Another good variety is ‘Black Butte’. ‘Marion’ berry is widely grown in the Pacific Northwest; the plant is very spiny and the berry is used mostly for canning, freezing, pies, and jam. -

Rubus Arcticus Ssp. Acaulis Is Also Appreciated

Rubus arcticus L. ssp. acaulis (Michaux) Focke (dwarf raspberry): A Technical Conservation Assessment Prepared for the USDA Forest Service, Rocky Mountain Region, Species Conservation Project October 18, 2006 Juanita A. R. Ladyman, Ph.D. JnJ Associates LLC 6760 S. Kit Carson Cir E. Centennial, CO 80122 Peer Review Administered by Society for Conservation Biology Ladyman, J.A.R. (2006, October 18). Rubus arcticus L. ssp. acaulis (Michaux) Focke (dwarf raspberry): a technical conservation assessment. [Online]. USDA Forest Service, Rocky Mountain Region. Available: http:// www.fs.fed.us/r2/projects/scp/assessments/rubusarcticussspacaulis.pdf [date of access]. ACKNOWLEDGMENTS The time spent and help given by all the people and institutions mentioned in the reference section are gratefully acknowledged. I would also like to thank the Wyoming Natural Diversity Database, in particular Bonnie Heidel, and the Colorado Natural Heritage Program, in particular David Anderson, for their generosity in making their records available. The data provided by Lynn Black of the DAO Herbarium and National Vascular Plant Identification Service in Ontario, Marta Donovan and Jenifer Penny of the British Columbia Conservation Data Center, Jane Bowles of University of Western Ontario Herbarium, Dr. Kadri Karp of the Aianduse Instituut in Tartu, Greg Karow of the Bighorn National Forest, Cathy Seibert of the University of Montana Herbarium, Dr. Anita Cholewa of the University of Minnesota Herbarium, Dr. Debra Trock of the Michigan State University Herbarium, John Rintoul of the Alberta Natural Heritage Information Centre, and Prof. Ron Hartman and Joy Handley of the Rocky Mountain Herbarium at Laramie, were all very valuable in producing this assessment. -

DICOTS Aceraceae Maple Family Anacardiaceae Sumac Family

FLOWERINGPLANTS Lamiaceae Mint family (ANGIOSPERMS) Brassicaceae Mustard family Prunella vulgaris - Self Heal Cardamine nutallii - Spring Beauty Satureja douglasii – Yerba Buena Rubiaceae Madder family DICOTS Galium aparine- Cleavers Boraginaceae Borage family Malvaceae Mallow family Galium trifidum – Small Bedstraw Aceraceae Maple family Cynoglossum grande – Houndstongue Sidalcea virgata – Rose Checker Mallow Acer macrophyllum – Big leaf Maple Oleaceae Olive family MONOCOTS Anacardiaceae Sumac family Fraxinus latifolia - Oregon Ash Toxicodendron diversilobum – Poison Oak Cyperaceae Sedge family Plantaginaceae Plantain family Carex densa Apiaceae Carrot family Plantago lanceolata – Plantain Anthriscus caucalis- Bur Chervil Iridaceae Iris family Daucus carota – Wild Carrot Portulacaceae Purslane family Iris tenax – Oregon Iris Ligusticum apiifolium – Parsley-leaved Claytonia siberica – Candy Flower Lovage Claytonia perforliata – Miner’s Lettuce Juncaceae Rush family Osmorhiza berteroi–Sweet Cicely Juncus tenuis – Slender Rush Sanicula graveolens – Sierra Sanicle Cynoglossum Photo by C.Gautier Ranunculaceae Buttercup family Delphinium menziesii – Larkspur Liliaceae Lily family Asteraceae Sunflower family Caryophyllaceae Pink family Ranunculus occidentalis – Western Buttercup Allium acuminatum – Hooker’s Onion Achillea millefolium – Yarrow Stellaria media- Chickweed Ranunculus uncinatus – Small-flowered Calochortus tolmiei – Tolmie’s Mariposa Lily Adendocaulon bicolor – Pathfinder Buttercup Camassia quamash - Camas Bellis perennis – English -

Yosemite National Park U.S

National Park Service Yosemite National Park U.S. Department of the Interior Invasive Plant Management Plan Update Environmental Assessment In 2008, Yosemite National Park created the Invasive Plant Management Plan (2008 IPMP) to provide a comprehensive, prioritized program of invasive plant prevention, early detection, control, systematic monitoring, and research. The 2009 Big Meadow Fire, and issues related to managing Himalayan blackberry (Rubus armeniacus) and other plants, highlighted the need for a more adaptive, programmatic plan that offers additional tools necessary to address the threat that invasive plants pose to park resources. Yosemite National Park is updating the 2008 IPMP to provide additional methods that can increase the effectiveness of the park’s invasive plant management efforts. Invasive The spread of invasive species is recognized as one of the major factors contributing to ecosystem change and instability throughout the world. An invasive species is “a non-native Species….. species whose introduction does, or is likely to cause, economic or environmental harm or What are they harm to human, animal, or plant health” (Executive Order 13112, 1999). These species have and why are the ability to displace or eradicate native species, alter fire regimes, damage infrastructure, and threaten human livelihoods. they a problem? Invasive species are changing the iconic landscapes of our national parks. In areas dominated by non-native plant species, native plant populations can be reduced to small, isolated populations, or even driven to local extinction. As native plants decline in numbers, so may the wildlife that depend on them for food. Invasive plants can harm the visitor’s experience by replacing the park’s spectacular and diverse displays of showy wildflowers with large, unattractive monocultures.