Urban Migrants and Hometown-Based Associations in Japan’S Urbanization

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Trip to Japan

Trip to Japan Contact us | turipo.com | [email protected] Trip to Japan Our trip to Japan from Tokyo to Kyoto Contact us | turipo.com | [email protected] Day 1 - Arrival to Tokyo Contact us | turipo.com | [email protected] Day 1 - Arrival to Tokyo 1. Tokyo Contact us | turipo.com | [email protected] Day 2 - Tokyo Contact us | turipo.com | [email protected] Day 2 - Tokyo 1. Tokyo Tokyo, Japan WIKIPEDIA Tokyo, officially Tokyo Metropolis, one of the 47 prefectures of Japan, has served as the Japanese capital since 1869. As of 2014 the Greater Tokyo Area ranked as the most populous metropolitan area in the world. The urban area houses the seat of the Emperor of Japan, of the Japanese government and more.. Contact us | turipo.com | [email protected] Day 3 - Tokyo Contact us | turipo.com | [email protected] Day 4 - Nikko Contact us | turipo.com | [email protected] Day 4 - Nikko 1. Nikko Nikko, Tochigi, Japan WIKIPEDIA Nikko may refer to: Contact us | turipo.com | [email protected] Day 5 - Nikko Contact us | turipo.com | [email protected] Day 5 - Nikko 1. Nikko Nikko, Tochigi, Japan WIKIPEDIA Nikko may refer to: 2. Nikko National Park Yumoto, Nikko, Tochigi Prefecture 321-1662, Japan Rating: 4 WIKIPEDIA Nikkō Naonal Park is a naonal park in the Kantō region, on the main island of Honshū in Japan. The park spreads over four prefectures: Tochigi, Gunma, Fukushima, and Niigata, and was established in 1934. Contact us | turipo.com | [email protected] Day 6 - Nikko to Tokyo Contact us | turipo.com | [email protected] Day 6 - Nikko to Tokyo 1. -

Hankyu Hanshin Holdings Securities Code: 9042 ANNUAL REPORT

Hankyu Hanshin Holdings Securities code: 9042 ANNUAL REPORT Hankyu Hanshin Holdings, Inc. ANNUAL REPORT 2016 Hankyu Inc. ANNUAL Hanshin Holdings, 2016 Growingthe Ground from Up ANNUAL REPORT 2016 Contents Key Facts Financial Section and Corporate Data 1 Group Management Philosophy 73 Consolidated Six-Year Summary 3 Corporate Social Responsibility (CSR) 74 Consolidated Financial Review 4 At a Glance 77 Business Risks 6 Location of Our Business Base 78 Consolidated Balance Sheets 8 Business Environment 80 Consolidated Statements of Income / 10 Performance Highlights (Consolidated) Consolidated Statements of Comprehensive Income 14 ESG Highlights 81 Consolidated Statements of Changes in Net Assets 83 Consolidated Statements of Cash Flows 84 Notes to the Consolidated Financial Statements Business Policies and Strategies 108 Major Rental Properties / Major Sales Properties 16 To Our Stakeholders 109 Major Group Companies 24 Special Feature: Anticipating Change, 110 Group History Pursuing Growth Opportunities 111 Investor Information 29 Providing Services that Add Value to Areas 32 Capitalising on Opportunities through Overseas Businesses 36 CSR and Value Enhancement in Line-Side Areas Search Index Group Overview 1–15, 38–39, 108–111 Core Businesses: Overview and Outlook 2016 Financial and Business Performances 38 Core Business Highlights 10–13, 17–19, 73–76 40 Urban Transportation Forecasts for Fiscal 2017 Onward 44 Real Estate Group: 22 Urban Transportation: 41 48 Entertainment and Communications Real Estate: 45 50 Travel Entertainment and -

Durham E-Theses

Durham E-Theses Transience and durability in Japanese urban space ROBINSON, WILFRED,IAIN,THOMAS How to cite: ROBINSON, WILFRED,IAIN,THOMAS (2010) Transience and durability in Japanese urban space, Durham theses, Durham University. Available at Durham E-Theses Online: http://etheses.dur.ac.uk/405/ Use policy The full-text may be used and/or reproduced, and given to third parties in any format or medium, without prior permission or charge, for personal research or study, educational, or not-for-prot purposes provided that: • a full bibliographic reference is made to the original source • a link is made to the metadata record in Durham E-Theses • the full-text is not changed in any way The full-text must not be sold in any format or medium without the formal permission of the copyright holders. Please consult the full Durham E-Theses policy for further details. Academic Support Oce, Durham University, University Oce, Old Elvet, Durham DH1 3HP e-mail: [email protected] Tel: +44 0191 334 6107 http://etheses.dur.ac.uk Iain Robinson Transience and durability in Japanese urban space ABSTRACT The thesis addresses the research question “What is transient and what endures within Japanese urban space” by taking the material constructed form of one Japanese city as a primary text and object of analysis. Chiba-shi is a port and administrative centre in southern Kanto, the largest city in the eastern part of the Tokyo Metropolitan Region and located about forty kilometres from downtown Tokyo. The study privileges the role of process as a theoretical basis for exploring the dynamics of the production and transformation of urban space. -

The Keihanshin Consortium for Fostering the Next

The Keihanshin Consortium for Fostering the Next Generation of Global Leaders in Research (K-CONNEX) Non-Tenure Program-Specific Assistant Professor Department of Electronic Science and Engineering, Graduate School of Engineering, Kyoto University November 20, 2015 In October 2014, Kyoto University, Osaka University and Kobe University decided to establish partnerships under a MEXT program, building a consortium for developing human resources in science and technology. The consortium, named as The Keihanshin Consortium for Fostering the Next Generation of Global Leaders in Research (K-CONNEX), promotes development and securement of excellent young researchers who will lead the future global academic community. We encourage such highly motivated young researchers to join the consortium through the following applications. 1. Target Research Areas Code No. 014KY1510 Job Type Program-Specific Assistant Professor with an annual salary No. Of 1 Positions Department of Electronic Science and Engineering, Graduate School of Engineering, Kyoto University Affiliation (Address: Kyoto University Katsura campus Nishigyo-ku, Kyoto 615-8530, Japan) Research Optical Engineering, Quantum Optoelectronics Fields We are recruiting top-class researchers who can develop artificial Research structural materials that can freely control light down to the Fields nanometer level. Applicants should be outstanding young (Details) researchers who aspire to “challenge the frontiers of physics” and “create new functions,” which the Department of Electronic Science and Engineering and the Photonics and Electronics Science and Engineering Center espouse, possess the advanced skills to do so, have already produced influential results in terms of benefiting society, and be recognized as having the talent to be a future PI. Term From the day of arrival at post to March 31, 2021 Discretionary labor system: Working hours are at the discretion of the worker with the standard working hours from 8:30 (starting Employment time) to 17:15 (ending time). -

The Keihanshin Consortium for Fostering the Next

The Keihanshin Consortium for Fostering the Next Generation of Global Leaders in Research (K-CONNEX) Non-Tenure Program-Specific Assistant Professor Research Center for Environmental Quality Management, Graduate School of Engineering, Kyoto University November 20, 2015 In October 2014, Kyoto University, Osaka University and Kobe University decided to establish partnerships under a MEXT program, building a consortium for developing human resources in science and technology. The consortium, named as The Keihanshin Consortium for Fostering the Next Generation of Global Leaders in Research (K-CONNEX), promotes development and securement of excellent young researchers who will lead the future global academic community. We encourage such highly motivated young researchers to join the consortium through the following applications. 1. Target Research Areas Code No. 015KY1510 Job Type Program-Specific Assistant Professor with an annual salary No. Of 1 Positions Research Center for Environmental Quality Management, Affiliation Graduate School of Engineering, Kyoto University (Address: 1-2 Yumihama, Otsu, 520-0811, Japan) Research Environmental Toxicology and Environmental Microbiology Fields We are recruiting a person who possesses the ability to evaluate the water environment risks due to trace contaminates and Research waterborne pathogens and to verify the benefits of controlling Fields them through water treatment. Applicants should be able to (Details) comprehensively evaluate the toxicity of endocrine disrupters, pharmaceuticals, agricultural chemicals, etc., using bioassay and conduct research that will lead to the setting of reduction goals. As for pathogens, applicants should be able to conduct independent research regarding not only indicator organisms but also viruses and antibiotic-resistant bacteria. Both trace contaminates and pathogens are important in terms of water environment risk management, and applicants should possess knowledge of environmental engineering and be able to conduct research related to both. -

Urban Agglomerations 2014 Wall Chart

United Nations • Department of Economic and Social Affairs • Population Division • www.unpopulation.org Urban Agglomerations 2014 Average annual 2014 population residing Average annual 2014 population residing Average annual 2014 population residing Population rate of change in agglomeration, Population rate of change in agglomeration, Population rate of change in agglomeration, (millions) Rank* (percentage) as percentage of (millions) Rank* (percentage) as percentage of (millions) Rank* (percentage) as percentage of Total Urban Total Urban Total Urban Urban agglomeration Country 1990 2014 2030 1990 2014 2030 2010–2015 2025–2030 population population Urban agglomeration Country 1990 2014 2030 1990 2014 2030 2010–2015 2025–2030 population population Urban agglomeration Country 1990 2014 2030 1990 2014 2030 2010–2015 2025–2030 population population A Hims (Homs)66 Syrian Arab Republic 0.6 1.6 2.5 404 291 245 4.0 2.1 7.3 12.7 Port-au-Prince109 Haiti 1.1 2.4 3.5 213 185 165 2.6 1.9 22.7 39.5 Abidjan Côte d'Ivoire 2.1 4.7 7.8 106 77 62 3.2 2.9 22.6 42.3 Hiroshima Japan 2.0 2.2 2.2 120 207 280 0.5 -0.1 1.7 1.8 Portland United States of America 1.2 2.0 2.3 204 229 261 1.5 0.9 0.6 0.8 Abu Zaby (Abu Dhabi) United Arab Emirates 0.3 1.1 1.6 459 424 385 5.3 1.8 11.8 13.8 Hohhot67 China 0.6 1.7 2.4 381 269 252 3.8 1.2 0.1 0.2 Porto110 Portugal 1.2 1.3 1.4 209 358 426 0.2 0.7 12.2 19.4 Abuja1 Nigeria 0.3 2.3 4.9 460 191 108 5.9 3.9 1.3 2.7 Hong Kong68 China, Hong Kong SAR 5.8 7.3 7.9 29 44 61 0.7 0.4 100.0 100.0 Pôrto Alegre Brazil 2.7 3.6 4.0 77 107 -

Estimation of Day-Long Population Dynamics of Workers Using Nation-Wide Statistical Data and Its Application to the Keihanshin Metropolitan Area, Japan

Estimation of Day-long Population Dynamics of Workers Using Nation-wide Statistical Data and its Application to the Keihanshin Metropolitan Area, Japan Keisuke Himoto 1, Junpei Kimata 2, Tomoaki Nishino 3 and Takeyoshi Tanaka 4 1 Disaster Prevention Research Institute, Kyoto University , Kyoto , Japan 2 Construction Division, Aichi Prefectural Government, Nagoya, Japan 3 Department of Architecture, Kobe University, Kobe, Hyogo, Japan 4 Research Center for Disaster Mitigation of Cultural Heritage, Ritsumeikan University, Kyoto, Kyoto, Japan email corresponding author: [email protected] Abstract Extent of fatality due to natural disaster depends largely on spatial distribu- tion of population at the moment the disaster occurs. In this study, a com- putational model for estimating day-long spatio-temporal distribution of workers was developed by using a number of nation-wide statistical data such as "Population Census", "Survey on Time Use and Leisure Activi- ties", and “Economic Census”. The model estimates behavior of individual workers by considering their attributes including gender, occupation, place of work and residence, and whether he/she works at home or not. As a case study, the proposed model was applied to the Keihanshin (Kyoto-Osaka- Kobe) Metropolitan Area, one of the largest metropolitan areas in Japan. Estimated instantaneous number of workers unable to return home be- comes the maximum of about 1.4 million between 10:00 and 16:00, around which the utmost disorder in association with traffic disruption is expected if an earthquake strikes. 2 CUPUM conference papers 1. Introduction Appearance of disaster considerably changes due to the time of its occur- rence. -

TOD Practice in Japan Tokyo, a Global City Created by Railways

TOD Practice in Japan Tokyo, A Global City Created by Railways This is a partial English translation of a book titled as “TOD Practice in Japan; Tokyo, A Global City Created by Railways”. (Edited and written by Takashi Yajima and Hitoshi Ieda. Published by The Institute of Behavioral Sciences) The copyright for the original text is held by the authors noted above, the publisher, and the sources noted in the diagrams and figures in the book. The copyright for the translation is held by JICA (Chapter 1), and the Ministry of Land, Infrastructure, Transport and Tourism (Chapters 2 - 4). The book was proofread by Takashi Yajima, Takashi Yamazaki, Masafumi Ota and Mizuo Kishita. (1st Edition, published in Mar. 2019) Edited and written by Takashi Yajima and Hitoshi Ieda [Study Group on TOD] Takashi Yajima, Hitoshi Ieda, Takayuki Kishii, Tsuneaki Nakano, Takashi Yamazaki, Masafumi Ota, Hisao Okuma, Hiroyuki Suzuki, Shinichi Hirata and Hajime Daimon Table of contents The contents of the original are as below. The sections considered necessary in order for persons from overseas to gain an understanding of Japan’s practice on TOD were selected for translation. Specifically, those are the sections that give an overview of Japan’s urban development and transportation, and sections relating to the former Japanese National Railways/current East Japan Railway Company as well as Tokyu Corporation as typical examples clearly illustrating TOD practice in Japan. Translated sections are indicated in the contents with an asterisk (*). Introduction Tokyo: The -

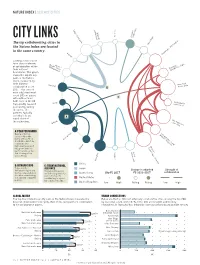

CITY LINKS Metro Area E Top Collaborating Cities in Cambridge the Nature Index Are Located in the Same Country

NATURE INDEX | SCIENCE CITIES Tsukuba Tokyo metro area metro area Nagoya London CITY LINKS metro area e top collaborating cities in Cambridge the Nature Index are located in the same country. Sendai Baltimore - Washington Leading science cities form dense networks Osaka -Kyoto Kobe - of collaboration within (Keihanshin) Chicago - their national Naperville - Elgin boundaries. This graph shows the top 25 city pairs in the Nature Index, measured by their bilateral Nanjing New York collaboration score B metro area (CS) — the sum of each city’s fractional count (FC) on papers with authors from C both cities in the 82 Philadelphia high-quality research Hefei metro area journals tracked by the index. The partners typically contribute to an A equal share of San Francisco the authorship. - San Jose Beijing A: PEAK PERFORMER Los Angeles - Long Beijing is the top Beach - Anaheim science city in the index, with an FC of Changchun 2,142.53 in 2017. Its contribution to high-quality research Boston - Cambridge - Newton has grown over the Wuhan past six years, as has Seoul Daejeon metro area that of many cities across China. Shanghai China B: DYNAMIC DUO C: TRANSNATIONAL Tokyo and the ALLIANCE Japan Keihanshin region are Change in adjusted Strength of Beijing and New York collaboration the top collaborators in are the only global city South Korea City FC 2017 FC 2012–2017 the index, contributing pair in the top 25, to a joint CS of 442.88 contributing to a joint United States in 2017. CS of 125.73 in 2017. United Kingdom Low High Falling Rising Low High GLOBAL MATCH URBAN CONNECTIONS The top ve international city pairs in the Nature Index, measured by Below are the top 10 most externally collaborative cities among the top 200 bilateral collaboration score (CS). -

Northern and Western Kinki Region Shuichi Takashima

Railwa Railway Operators Railway Operators in Japan 11 Northern and Western Kinki Region Shuichi Takashima Keihanshin economic zone based on a from cities in the south. As a result, the Region Overview contraction of the Chinese characters population density in these northern forming parts of each city name. areas is low, despite the proximity to This article discusses railway lines in parts However, to some extent, each city is still Keihanshin. Shiga Prefecture borders the of four prefectures in the Kinki region: an economic entity in its own right, eastern side of Kyoto Prefecture and has Shiga, Kyoto, Osaka and Hyogo. The making the region somewhat different long played a major role as a three largest cities in these four prefectures from the huge conurbation of transportation route to eastern Japan and are Kyoto, Osaka and Kobe. Osaka was Metropolitan Tokyo. the Hokuriku region. y Japan’s most important commercial centre Topography is the main reason for this until it was surpassed by Tokyo in the late difference. Metropolitan Tokyo spreads 19th century. Kyoto is the ancient capital across the wide Kanto Plain, while Kyoto, Outline of Rail Network (where the Emperors resided from the 8th Osaka and Kobe are separated by Operators to 19th centuries), and is rich in historical highlands that (coupled with the nearby The region’s topography has determined sites and relics. Kobe had long been a sea and rivers) have prevented Keihanshin the configuration of the rail network. In major domestic port and became the most from expanding to the same extent as the Metropolitan Tokyo, lines radiate like important international port serving Metropolitan Tokyo. -

Urbanization and Development in Japan

Supported by the Japan Shipbuilding Industry Foundation (Chairman, Ryoichi Sasakawa) "Population and Development" Series No.3 Urbanization and Development in Japan Overview and Introduction by Toshio Ku roda Urbanization of the Population and Development -New Tasks- by Toshio Kuroda Demographic Urbanization and Economic _ _____ =.D-=.e..:...ve::..:l-=.opment by Yoichi Okazaki Changes in Geographical Distribution of Japanese Population by Atsushi Otomo Fluctuation of Migration Pattern and Human Development by Sumiko Uchino A Components Analysis of Urbanization in Postwar Japan by Tatsuya Itoh Overpopulation and Depopulation: Problem of Development by Hiroaki Shimizu MARCH 1986 The Asian Population and Development Association (foundation) ERRATUM In Table 1 on page 8~ Migration rate column on right should be replaced hy the column given below. Table 1 Fluctuations in Total Migration and Intra and Inter- Prefectural Migration (1954 - 1984) Year Total />ligra Migration within Nigration migrants! ) talon prefectures Interprefectural rate2 ) No. of Migra No. of Migra migrants tion migrants tion rate rate % % 1954 5,498,318 6,27% 3,145,504 3.59 2,352,814 2.68 1955* 5,140,569 5.80 2,913,517 3.29 2,227,052 2.51 1956 4,859,625 5.43 2,737,844 3.06 2,121,781 2.37 1957 5,268,248 5.83 2,887,932 3.20 2,380,316 2.ti~ 1958 5,294,291 5.81 2,913,665 3.20 2,380,626 2.li1 1959 5,357,658 5,82 2,915,025 3.17 2,442,633 2.6;J 1960* 5,652,659 6.09 2,972,940 3.20 2,679,719 2.i:l9 1961 6,012,494 6.42 3,060,105 3.27 2,952,389 :3. -

A New Pass for Overseas Visitors to Japan:Osaka-Tokyo Hokuriku Arch

November 4, 2015 East Japan Railway Company West Japan Railway Company A new pass for overseas visitors to Japan: Osaka-Tokyo Hokuriku Arch Pass ~This new pass enables economical travel from Osaka and Tokyo to the Hokuriku area!~ JR-East and JR-West have up to now served many passengers through the sales of economical unlimited-travel passes for foreign visitors to Japan. So that foreign visitors to Japan can enjoy touring across a wide area, we are now introducing the Osaka-Tokyo Hokuriku Arch Pass for economical travel from Osaka and Tokyo to the Hokuriku area. With this pass, visitors can travel from the Kansai, Narita, and Haneda international airports to the Hokuriku area by Hokuriku Shinkansen, limited express trains, and other services. In conjunction with this, we are preparing discount and gift benefits that can be used for Hokuriku area leisure-facilities, buses, trains, etc. So that as many foreign visitors as possible can get more enjoyment out of their travel, together with the people of the region, we will be working even harder to publicize sightseeing routes extending across a wide area. ◇ Name Osaka-Tokyo Hokuriku Arch Pass ◇ Usage period Can be used throughout the year, beginning on April 1, 2016 (Friday) ◇ Valid period For 7 continuous days ◇ Sales locations For exchange ticket sales locations (overseas) and sales/exchange locations (in Japan) please see the attachment. ◇ Price Purchased abroad: Adults (age 12 and up) ¥24,000, children (age 6 to 11) ¥12,000 Purchased in Japan: Adults (age 12 and up) ¥25,000, children (age 6 to 11) ¥12,500 ◇ Main validity Unlimited travel for ordinary car reserved seats on the limited express trains (Shinkansen included), express trains, and local trains of Kansai-airport, the Kansai area, the Hokuriku area, Tokyo Metropolitan District and Narita and Haneda Airports (in the case of the Haruka limited express, ordinary car non-reserved seats).