Mapping Innovation for Rural Development in Umzinyathi District

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Kwazulu-Natal Province Facility, Sub-District and District

KWAZULU-NATAL PROVINCE FACILITY, SUB-DISTRICT AND DISTRICT Facility Posts Period Field of Study Province District Sub-District Facility 2017 Audiologist kz KwaZulu-Natal Province kz Amajuba District Municipality kz Dannhauser Local Municipality kz Dannhauser CHC 1 kz Dannhauser Local Municipality Total 1 kz Newcastle Local Municipality kz Madadeni Hospital 1 kz Newcastle Local Municipality Total 1 kz Amajuba District Municipality Total 2 kz eThekwini Metropolitan Municipality kz eThekwini Metropolitan Municipality Sub kz Hlengisizwe CHC 1 kz Tongaat CHC 1 kz eThekwini Metropolitan Municipality Sub Total 2 kz eThekwini Metropolitan Municipality Total 2 kz Harry Gwala District Municipality kz Greater Kokstad Local Municipality kz East Griqualand and Usher Memorial Hospital 1 kz Greater Kokstad Local Municipality Total 1 kz Ubuhlebezwe Local Municipality kz Christ the King Hospital 1 kz Ubuhlebezwe Local Municipality Total 1 kz Umzimkhulu Local Municipality kz Rietvlei Hospital 1 kz St Margaret's TB MDR Hospital 1 kz Umzimkhulu Local Municipality Total 2 kz Harry Gwala District Municipality Total 4 kz iLembe District Municipality kz Mandeni Local Municipality kz Sundumbili CHC 1 kz Mandeni Local Municipality Total 1 kz Ndwedwe Local Municipality kz Montebello Hospital 1 kz Ndwedwe Local Municipality Total 1 kz iLembe District Municipality Total 2 kz Ugu District Municipality kz Hibiscus Coast Local Municipality kz Gamalakhe CHC 1 kz Hibiscus Coast Local Municipality Total 1 kz Ugu District Municipality Total 1 kz uMgungundlovu District Municipality -

Kwa-Zulu Natal No Fee Schools 2017

KWA-ZULU NATAL NO FEE SCHOOLS 2017 NATIONAL EMIS NAME OF SCHOOL SCHOOL PHASE ADDRESS OF SCHOOL EDUCATION DISTRICT QUINTILE LEARNER NUMBER 2017 NUMBERS 2017 500101195 A.M. MOOLLA SECONDARY SCHOOL S KWASHANGASE TRIBAL AUTHORITY ILEMBE 1 169 500100270 ABAQULUSI HIGH SCHOOL S Bhadeni Area ZULULAND 1 583 500100307 ABATHWA PRIMARY SCHOOL P Ogazini Area UMZINYATHI 1 253 500101010 ALPHA PRIMARY SCHOOL P KROMMELENBOOG FARM ZULULAND 1 14 500101121 ALVA PRIMARY SCHOOL C FREIBERG FARM UMZINYATHI 1 207 500101528 AMAHOBE PRIMARY SCHOOL P AMAJUBA FOREST AMAJUBA 1 134 500493654 AMAKHUZE SECONDARY SCHOOL S Makhongwana Location HARRY GWALA 1 399 500101713 AMAKHWATHA PRIMARY SCHOOL C 55I STRETCH CRESCENT ROAD ZULULAND 1 886 500101861 AMANDLAKAPHELI PRIMARY SCHOOL P Kwalembe Tribal Authority UGU 1 128 500342509 AMANDLAKHE PRIMARY SCHOOL P Care of kwa-Qumbu UMGUNGUNDLOVU 1 150 500308062 AMANDLALATHI PRIMARY SCHOOL P VULAMEHLO MUNICIPALITY UGU 1 261 500102416 AMAPHUPHESIZWE HIGH SCHOOL S Umphumulo Mission ILEMBE 1 553 500102453 AMAPHUTHU HIGH SCHOOL S Thulani area KING CETSHWAYO 1 243 500102527 AMAQHAWE PRIMARY SCHOOL P MAKWAKWA AREA UMKHANYAKUDE 1 819 500102786 AMATIMOFU PRIMARY SCHOOL P EMPAPHALA RESERVE KING CETSHWAYO 1 110 500102897 AMAYESE PRIMARY SCHOOL P Ngono Tribal Authority, Mfongosi Area, Amayese road KING CETSHWAYO 1 87 500308876 AMAZONDI SECONDARY SCHOOL S Mpotholo Area Kwazondi tribal authority KING CETSHWAYO 1 384 500423613 ANTIOCH JUNIOR SECONDARY SCHOOL P ANTIOCH LOCATION HARRY GWALA 1 265 500103489 ARDEN PRIMARY SCHOOL P D 158 UMGUNGUNDLOVU -

Draft 2019/20 IDP Prepared by Umzinyathi District Municipality 1 29 March 2019

Table of Contents SECTION A: EXECUTIVE SUMMARY ................................................................................................................ 11 1 WHO ARE WE ............................................................................................................................................... 11 1.1 SPATIAL LOCATION WITHIN KZN PROVINCE .......................................................................................................... 11 1.1.1 Demographics Trends and Characteristics .......................................................................................... 15 1.2 INFRASTRUCTGURE ANALYSIS ............................................................................................................................. 16 1.2.1 Water .................................................................................................................................................. 16 1.2.2 Sanitation ............................................................................................................................................ 17 1.3 LONG TERM VISION ......................................................................................................................................... 18 1.3.1 IDP Development Process, Phases And Key Timeframes .................................................................... 18 1.4 KEY DEVELOPMENTAL CHALLENGES FACING THE MUNICIPALITY AND PROPOSED INTERVENTIONS ................................... 25 1.5 HIGH LEVEL MUNICIPAL PROGRAMMES AND MONITORING -

Msinga Municipal Idp 2017 2022

P a g e | KZ2 44 MSINGA MUNICIPALITY’S 4TH GENERATION INTEGRATED DEVELOPMENT PLAN 2017/2022 Developed in house PRIVATE BAG X530 TUGELLA FERRY 3010 033 4930762/3/4 Email: [email protected] [email protected] 1 Msinga Municipality’s 4th Generation IDP 2017 - 2022 MSINGA MUNICIPALITY 2017-2022 IDP Table of Contents SECTION A .............................................................................................................................................................................. 1 A: EXECUTIVE SUMMARY .................................................................................................................................................. 1 1. EXECUTIVE SUMMARY ............................................................................................................................................... 1 1.1 INTRODUCTION ................................................................................................................................................. 1 1.2 MSINGA MUNICIPALITY ................................................................................................................................. 1 1.2.2 “HOW WAS THIS INTEGRATED DEVELOPMENT PLAN DEVELOPED?” 2 a) The UMzinyathi Framework Plan ............................................................................................................................. 2 TABLE 1. Compliance with Process Plan ......................................................................................................................... 3 b) Community -

Nqutu Municipal Housing Sector Plan

TABLE OF CONTENTS DESCRIPTION PAGE NO. Part i Executive Summary 6 Acknowledgements 8 1 Introduction 9 2 Terms of Reference 10 3 Purpose of this Strategic Housing Plan 13 4 Methodology 13 4.1 Data Collection and literature Research 13 4.2 Feasibility Study: Stakeholders Interviews 13 4.3 Proposed Study; Socio Economic 13 4.5.1 Objectives 14 4.6 Social Survey 14 Part ii 5 Housing Legislative Instruments 15 5.0 Contextual Outline 15 5.1.1 Selected Provincial & National Policies 15 5.1.1.1 The Constitution of South Africa 15 5.1.1.2 The National Environmental Management Act 16 5.1.1.3 The housing Act 17 Additional Rural Guidelines (KZN) 31/07/2003 17 5.1.1.4 The Local Government Transition Act 18 5.1.1.5 The Environmental Conservation Act 18 The National Guidelines for Housing in Rural Areas 01/03 18 Part iii 6.0 Local Context 19 6.1 Spatial Context 19 6.2 Demographic Context 20 7.0 Biophysical Context 26 7.1 Climate 26 7.2 Rainfall 26 7.3 Temperatures 27 7.4 Winds 27 7.5 Topography 28 7.6 Geology 29 7.7 Hydrology 30 7.7.1 Surface Water Resources 30 7.7.2 Ground Water 31 7.8 Vegetation 33 7.9 Grassland 34 7.10 Crops 35 7.11 Vegetation Status 37 8.0 Bulk Infrastructure 38 8.1 Electricity 38 8.2 Roads 38 8.3 Roads & Economic Benefit 39 8.4 Storm water 40 8.5 Water Supply 40 8.6 Sewerage 40 9.0 The Economic Context 41 9.1 Objectives 41 9.2 Pilot Project 41 9.3 Accessibility 41 9.4 Community Support 41 2 9.4 Diary Farming & Other Agric Projects 42 9.5 Eqhudeni Gravel Road Upgrade 47 Part IV 10.1 Housing Development Legislative Guidelines 51 10.2 -

Umzinyathi District Profile

2 PROFILE: UMZINYATHI DISTRICT PROFILE PROFILE: UMZINYATHI DISTRICT PROFILE 3 CONTENT 1. Executive Summary ....................................................................................................... 6 2. Brief overview ................................................................................................................ 7 2.1. Location .................................................................................................................. 7 3. Social Development ....................................................................................................... 9 3.1. Key Demographics .................................................................................................. 9 3.1.1. Population and Household Profile ........................................................................ 9 3.1.2. Age and Gender Profile ...................................................................................... 10 3.2. Health .................................................................................................................... 10 3.3. Covid-19 ................................................................................................................ 12 3.4. Poverty and Inequality ........................................................................................... 12 3.6. Education .............................................................................................................. 13 4. Economic Drivers ........................................................................................................ -

Export This Category As A

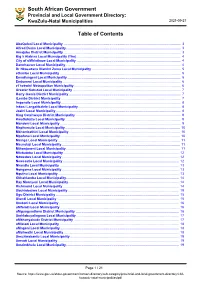

South African Government Provincial and Local Government Directory: KwaZulu-Natal Municipalities 2021-09-27 Table of Contents AbaQulusi Local Municipality .............................................................................................................................. 3 Alfred Duma Local Municipality ........................................................................................................................... 3 Amajuba District Municipality .............................................................................................................................. 3 Big 5 Hlabisa Local Municipality (The) ................................................................................................................ 4 City of uMhlathuze Local Municipality ................................................................................................................ 4 Dannhauser Local Municipality ............................................................................................................................ 4 Dr Nkosazana Dlamini Zuma Local Municipality ................................................................................................ 5 eDumbe Local Municipality .................................................................................................................................. 5 Emadlangeni Local Municipality .......................................................................................................................... 6 Endumeni Local Municipality .............................................................................................................................. -

Msinga Municipality Spatial Development Framework 2020

MSINGA MUNICIPALITY SPATIAL DEVELOPMENT FRAMEWORK DRAFT STATUS QUO REPORT JUNE 2020 MSINGA MUNICIPALITY SPATIAL DEVELOPMENT FRAMEWORK 2020 Contents CHAPTER 1: BACKGROUND AND PURPOSE 1 1.1 INTRODUCTION 1 1.2 PURPOSE OF THE REPORT 1 1.3 WHAT IS A SPATIAL DEVELOPMENT FRAMEWORK 2 1.4 LEGAL AND POLICY IMPERATIVES 3 1.5 RELATIONSHIP WITH OTHER PLANS 4 1.6 DEFINING THE STUDY AREA 5 1.7 STRUCTURE OF THIS DOCUMENT 9 1.8 STUDY OBJECTIVES/ISSUES TO BE ADDRESSED 9 1.9 MUNICIPAL SPATIAL STRUCTURE AND DEVELOPMENT INFORMANTS 11 CHAPTER 2: STATUS QUO OF MSINGA MUNICIPALITY 12 2.1 LEGISLATIVE ENVIRONMENT 12 2.1.1 SOUTH AFRICAN CONSTITUTION AND PRINCIPLES OF SUSTAINABLE DEVELOPMENT (NO. 108 OF 1196) ..................................................................................................................................... 12 2.1.2 MUNICIPAL SYSTEMS ACT (NO. 32 OF 2000) ........................................................................... 12 2.1.3 NATIONAL ENVIRONMENTAL MANAGEMENT ACT (NO. 107 OF 1998) ................................... 14 2.1.4 SOCIAL HOUSING ACT (NO.16 OF 2008) .................................................................................. 14 2.1.5 THE KWAZULU-NATAL HERITAGE ACT (NO 4 OF 2008) ........................................................... 16 2.1.6 SPLUMA (NO 16 OF 2013) ........................................................................................................ 17 2.2 POLICY ENVIRONMENT 21 2.2.1 PROVINCIAL GROWTH AND DEVELOPMENT STRATEGY ......................................................... -

Umzinyathi District Municipality: Biodiversity Sector Plan

uMzinyathi District Municipality: Biodiversity Sector Plan EZEMVELO KZN WILDLIF E Version: Version 1.0 BIODIVERSITY SECTOR PLA N Date: February 2014 i Biodiversity Sector Plan - uMzinyathi District Municipality 2014 Document Details Authored by: Ntando Ninela & Felicity Elliott Ezemvelo KZN Wildlife P.O. Box 13053 Cascades, 3202 Document is available from: Ezemvelo KZN Wildlife website, www.kznwildlife.com This guideline should be cited as: Ezemvelo KZN Wildlife (2014), uMzinyathi Biodiversity Sector Plan,V1.0, Unpublished Report of Ezemvelo KZN Wildlife, Biodiversity Conservation Planning Division, Ezemvelo KZN Wildlife, P. O. Box 13053, Cascades, Pietermaritzburg. RECOMMENDED Title Name Signature Date Chairperson: EKZNW , SOCC Chairperson: EKZNW , Operations Committee Chief Executive Officer EKZNW APPROVED Chairperson: KZN Nature Conservation Board F E B R UA R Y 2 0 1 4 - Ve rs i o n 1 .0 II Biodiversity Sector Plan - uMzinyathi District Municipality 2014 Acknowledgements Specialists involved in the development, consulting or review during production of the uMzinyathi District Biodiversity Sector Plan include the following key persons. Name Position Affiliation Dr Boyd Escott Manager: Biodiversity Spatial Planning & Information & Acting GIS Analysis Terrestrial Debbie Jewitt Biodiverty Research & Assessment Ezemvelo KZN Wildlife (Ecosystem ecologist) Felicity Elliott Biodiversity Spatial Planning& Information (Bioregional Planning) Heidi Snyman Biodiversity Spatial Planning& Information (Cartography) Bimal Naidoo Biodiversity Spatial -

Umzimyathi District Municipality, Kzn District Development Model Profile and Analysis

District Profile Report 2019 UMZIMYATHI DISTRICT MUNICIPALITY, KZN DISTRICT DEVELOPMENT MODEL PROFILE AND ANALYSIS Draft Version 04 06 February 2020 P a g e 1 | 110 District Profile Report 2019 SOURCE DOCUMENTS REFERENCED Name of Document Date of version Author/owner District Growth and Development Plan Adopted: August 2018 UDM and LMs District Municipal Spatial Development Framework Draft: March 2019 UDM District Integrated Development Plan Adopted: May 2019 UDM Umvoti Integrated Development Plan Adopted: June 2019 Umvoti LM Endumeni Integrated Development Plan Adopted: May 2019 Endumeni LM Msinga Integrated Development Plan Adopted: May 2019 Msinga LM Nquthu Integrated Development Plan Adopted: May 2019 Nquthu LM District Service Delivery Budget Implementation Plan 2019/20-2020/21 UDM Umzinyathi District Rural Development Plan March 2019 Department of Rural Development and Land Reform, UDM, LMs Umzinyathi District Profile: Spatial analysis Department of Rural Development and Land Reform Umzinyathi District Municipality: Draft Final Report Local Economic January 2018 UDM Development Strategy Provincial Local Economic Development Plan with Project Book per May 2018 COGTA District Super Cross Data 2016 Stats SA The South African MPI: Poverty Index 2014 Stats SA National Spatial Development Framework Draft: April 2019 Department of Rural Development and Land Reform State of Local Government Report June 2019 COGTA, Provincial Treasury Umzinyathi Family of Municipalities KZN Provincial overview: assessment of Municipalities July 2019 COGTA, -

Kwazulu-Natal

KwaZulu-Natal Municipality Ward Voting District Voting Station Name Latitude Longitude Address KZN435 - Umzimkhulu 54305001 11830014 INDAWANA PRIMARY SCHOOL -29.99047 29.45013 NEXT NDAWANA SENIOR SECONDARY ELUSUTHU VILLAGE, NDAWANA A/A UMZIMKULU KZN435 - Umzimkhulu 54305001 11830025 MANGENI JUNIOR SECONDARY SCHOOL -30.06311 29.53322 MANGENI VILLAGE UMZIMKULU KZN435 - Umzimkhulu 54305001 11830081 DELAMZI JUNIOR SECONDARY SCHOOL -30.09754 29.58091 DELAMUZI UMZIMKULU KZN435 - Umzimkhulu 54305001 11830799 LUKHASINI PRIMARY SCHOOL -30.07072 29.60652 ELUKHASINI LUKHASINI A/A UMZIMKULU KZN435 - Umzimkhulu 54305001 11830878 TSAWULE JUNIOR SECONDARY SCHOOL -30.05437 29.47796 TSAWULE TSAWULE UMZIMKHULU RURAL KZN435 - Umzimkhulu 54305001 11830889 ST PATRIC JUNIOR SECONDARY SCHOOL -30.07164 29.56811 KHAYEKA KHAYEKA UMZIMKULU KZN435 - Umzimkhulu 54305001 11830890 MGANU JUNIOR SECONDARY SCHOOL -29.98561 29.47094 NGWAGWANE VILLAGE NGWAGWANE UMZIMKULU KZN435 - Umzimkhulu 54305001 11831497 NDAWANA PRIMARY SCHOOL -29.98091 29.435 NEXT TO WESSEL CHURCH MPOPHOMENI LOCATION ,NDAWANA A/A UMZIMKHULU KZN435 - Umzimkhulu 54305002 11830058 CORINTH JUNIOR SECONDARY SCHOOL -30.09861 29.72274 CORINTH LOC UMZIMKULU KZN435 - Umzimkhulu 54305002 11830069 ENGWAQA JUNIOR SECONDARY SCHOOL -30.13608 29.65713 ENGWAQA LOC ENGWAQA UMZIMKULU KZN435 - Umzimkhulu 54305002 11830867 NYANISWENI JUNIOR SECONDARY SCHOOL -30.11541 29.67829 ENYANISWENI VILLAGE NYANISWENI UMZIMKULU KZN435 - Umzimkhulu 54305002 11830913 EDGERTON PRIMARY SCHOOL -30.10827 29.6547 EDGERTON EDGETON UMZIMKHULU -

Ethembeni Cultural Heritage

eThembeni Cultural Heritage Box 20057 Ashburton 3213 Pietermaritzburg Telephone 033 326 1136 / 082 655 9077 / 082 529 3656 Facsimile 086 672 8557 [email protected] Company registration number CK 94/022770/23 VAT registration number 4690238268 eThembeni provides advice and guidance concerning heritage landscapes, places and activities, particularly in the context of development May 2012 eThembeni Specialises in the Following Activities: Heritage Impact Assessments (HIAs) as required by the National Environmental Management Act 107 of 1998 as amended (NEMA), in compliance with Section 38 of the National Heritage Resources Act 25 of 1999 as amended (NHRA). Staff members are accredited to work throughout South Africa and will undertake work elsewhere in Africa. We identify heritage resources and recommend appropriate mitigation measures before development occurs. Although we do not undertake Palaeontological Impact Assessments we do refer clients to specialists in this field. Ancestral grave exhumation and reburial, including negotiation with families. Heritage resource management components of Strategic Development Plans and Environmental Management Frameworks. Excavation and management of archaeological sites. Preparation of nomination proposals to heritage authorities for the declaration of heritage resources as National and Provincial Heritage Landmarks, including the compilation of Integrated Site Management Plans. We conduct all our activities within appropriate legal frameworks, to ensure that places and landscapes are managed