The Writing on the Wall

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

ELECTION PREVIEW 2006 1 Introduction/ Executive Summary 55783 Tabs 10/10/06 8:52 PM Page 1 Page PM 8:52 10/10/06 55783 Tabs 55783 Textx2 10/19/06 11:00 PM Page 3

55783_Covers 10/10/06 9:22 PM Page 2 ElectionElection previewpreview What’sWhat’s Changed,Changed, 20062006WhatWhat Hasn’tHasn’t andand WhyWhy 55783_Covers 10/10/06 9:22 PM Page 3 55783_TextX 10/19/06 5:56 AM Page 1 TABLE OF CONTENTS contents of Table Director’s Message . 3 Executive Summary . 5 TableStates to Watch. of. 7 Voting Systems: Widespread Changes, Problems . 12 Voting System Usage by State . 15 contentsVoter ID: Activity in the States and on the Hill . 19 Voter Verification Requirements by State . 22 Voter Registration Databases: A New Election Stumbling Block?. 23 Status of Statewide Voter Registration Databases. 28 Absentee Voting, Pre-election Voting and Provisional Voting Rules in the States. 30 State by State. 33 Methodology/Endnotes . 63 ELECTION PREVIEW 2006 1 Introduction/ Executive Summary 55783_Tabs 10/10/06 8:52 PM Page 1 55783_TextX2 10/19/06 11:00 PM Page 3 his was the year that election reform was finally supposed The election process changed more in 2006 than in any year message from the director Tto come together. since the disputed 2000 Presidential election. Consequently, on the eve of a national election in which control of Congress This was the year that the various deadlines embodied in the is in play — and two years from an open seat election for Help America Vote Act of 2002 (HAVA) took effect: the White House — it is vitally important to understand What’s computerized statewide voter lists, new voting technology, Changed, What Hasn’t and Why. improved accessibility for voters with disabilities and a host Messageof other procedural and legal requirements mandated as part As always, we have enjoyed preparing this report. -

5315 Annualreport2007.Pdf

~~ ?/(J Dillon Swenson Kabree Briggs Abigail Roberts Cecelia Roden Ahearn Rianne Rylie Cerino Tara Dailey Cole Woodley Andrew Fellows Tao Henning Matthew Guess Emily Corral Valencia Audrey Coffey Payton Sauer Jeremy Rowe Markie Montes Brent Russell Olivia Swank Marisa Carreno Matthew Crockett Baby Black Kylynn Fitzgerald Gavin Bailey Caylor Bird Ian Pearson Michael "Travis" Ewell PJoah Wyman , Baby Newman ~ustin Morgan r;, CU4 ~~ cT ~~ 1Ic~ ~o/~ ?~~ My family and I recently had an opportunity to share a little bit of the burden of these families with very prepare and serve dinner to the families staying at sick children so that they can focus their time, attention the Ronald McDonald House here in Salt Lake City. and energy on helping their children get well. It's important It was a Sunday evening, and after the initial scurrying work, and it's work the Ronald McDonald House of the about to get organized and set the food out, we Intermountain Area does very well. had a chance to interact with some of the families. There was the woman from Montana with her two In 2007, our Ronald McDonald House provided a "home daughters, ages two and four. The two-year-old is away from home" for approximately 1,728 families, who receiving treatment for a congenital heart defect, came to us from Montana, Idaho, Wyoming, Nevada, and the four-year-old was concerned that her sister and Utah. These families stayed with us for an average might not be drinking enough milk. There was the of seven days and, thanks to our board and hundreds of single mother from Nevada, whose premature baby volunteers, meals were waiting for them each evening. -

Research Report Report Number 704, November 2011 Nominating Candidates the Politics and Process of Utah’S Unique Convention and Primary System

Research Report Report Number 704, November 2011 Nominating Candidates The Politics and Process of Utah’s Unique Convention and Primary System HIGHLIGHTS For most of its history, Utah has used a convention- g Utah is one of only seven states that still uses a primary system to nominate candidates for elected office. convention, and the only one that allows political parties to preclude a primary election for major In the spring of election years, citizens in small caucus offices if candidates receive enough delegate votes. g Utah adopted a direct primary in 1937, a system meetings held throughout the state elect delegates to which lasted 10 years. represent them at county and state conventions. County g In 1947, the Legislature re-established a caucus- convention system. If a candidate obtained 70% or conventions nominate candidates for races solely within more of the delegates’ votes in the convention, he or she was declared the nominee without a primary. the county boundaries, while the state convention is used g In the 1990s, the Legislature granted more power to the parties to manage their conventions. In 1996, to nominate candidates for statewide offices or those the 70% threshold to avoid a primary was lowered to 60% by the Democratic Party. The Republican that serve districts that span multiple counties. At these Party made the same change in 1999. conventions, delegates nominate candidates to compete g Utah’s historically high voter turnout rates have consistently declined in recent decades. In 1960, for their party’s nomination in the primary election, or, 78.3% of the voting age population voted in the general election. -

Utah State University Commencement, 1960 – Main Campus

Utah State University DigitalCommons@USU Commencement Programs Students 6-3-1960 Utah State University Commencement, 1960 – Main Campus Utah State University Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.usu.edu/commencement Recommended Citation Utah State University, "Utah State University Commencement, 1960 – Main Campus" (1960). Commencement Programs. 2. https://digitalcommons.usu.edu/commencement/2 This Commencement Program - Main Campus is brought to you for free and open access by the Students at DigitalCommons@USU. It has been accepted for inclusion in Commencement Programs by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@USU. For more information, please contact [email protected]. /3. 2) 1'1 &o 6 17U7'-i4'-L<...--nut-,..::1 ..___ fro 9 r(L.,.-y.._ Annual Commencement Logan GEORGE NELSON FIELDHOUSE FRIDAY, J.UNE THIRD SATURDAY, JuNE FouRTH NINETEEN HUNDRED SIXTY THE ACADEMIC PROCESSION President and Board of Trustees 0 fficial Guests University Administrative Officers Faculties of the Various Colleges Candidates for Graduate Degrees Candidates for Baccalaureate Degrees DRESS The wearing of academic costume by faculty arc of a circle near the bottom. The arm extends and student participants at the time of Commence through the slit, giving the appearance of short ment Exercises has become traditional among sleeves. The hood consists of material similar universities. The color and pageantry of these to the gown and lined with the official academic occasions are designed to indicate the degree of color of the institution conferring the degree. I£ academic achievement of those who actively par the institution has more than one color, the chev ticipate in such exercises. In order for the ron is used to display the second color. -

Participation

PARTICIPATION A LOOK BACK AT 2007 Hinckley Institute Holds 2000th Hinckley Forum “OUR YOUNG, BEST MINDS MUST BE ENCOURAGED TO ENTER POLITICS.” Robert H. Hinckley 2 In This Issue Dr. J.D. Williams Page 3 Hinckley News Page 4 Internship Programs Page 8 Outstanding Interns Page 16 Scholarships Page 18 PARTICIPATION Hinckley Forums Page 20 Alumni Spotlights Page 25 Hinckley Staff Page 26 Donors Page 28 Hinckley Institute Holds 2000th Hinckley Forum Since 1965, the Hinckley Institute has held more than 2,000 Hinckley Forums (previously known as “Coffee & Politics”) featuring local, national, and international political leaders. Hinckley Forums provide University of Utah students and the surrounding community intimate access to and interaction with our nation’s leaders. Under the direction of Hinck- ley Institute assistant director Jayne Nelson, the Hinckley Institute hosts 65-75 forums each year in the newly renovated Hinckley Caucus Room. Partnerships with supporting Univer- sity of Utah colleges and departments, local radio and news stations, our generous donors, and the Sam Rich Program in International Politics ensure the continued success of the Hinckley Forums program. University of Utah students can now receive credit for attend- ing Hinckley Forums by enrolling in the Political Forum Series course (Political Science 3910). All Hinckley Forums are free and open to the public. For a detailed listing of 2007 Hinckley Forums, refer to pages 20 – 24. Past Hinckley Forum Guests Prince Turki Al-Faisal Archibald Cox Edward Kennedy Frank Moss Karl Rove Al Saud Russ Feingold William Lawrence Ralph Nader Larry Sabato Norman Bangerter Gerald Ford Michael Leavitt Richard Neustadt Brian Schweitzer Robert Bennett Jake Garn Richard Lugar Dallin H. -

3-18-14 Transcript Bulletin

FRONT PAGE A1 Dr. Rich is here to help your child grow up Pediatrician Dr. Steven Rich strong and healthy. Yay! will help you feel comfortable and confident every step of the way.Same-day appointments are usually available. Call 435-882-9035.TOOELE RANSCRIPT 196 E. 2000 North, SuiteTooele 100 T SERVING TOOELE COUNTY BULLETIN SINCE 1894 Steven Rich, D.O. TUESDAY March 18, 2014 www.TooeleOnline.com Vol. 120 No. 83 $1.00 2/6/14 12:45 PM 75208_MOUN_Yay_4x3c.indd 1 Roadside walk ends man’s life by Lisa Christensen STAFF WRITER A Tooele man was killed Monday morning when he was struck by a car while walking on an area roadway. James Wilson, 41, was struck and killed by a car near the intersection of Lodestone Way and Utah Avenue by Ninigret Industrial Depot at about 7 a.m. Chief Ron Kirby of the Tooele City Police Department said Wilson was wearing dark clothing and was difficult to see in the early, pre-dawn hour. The driver, also a local man, was report- edly on his way to Grantsville. Utah Avenue, between state Route 112 and the depot turn- off, was closed for more than two hours while officers attended to the scene and investi- SEE ROADSIDE PAGE A9 ➤ FRANCIE AUFDEMORTE/TTB PHOTO County’s Lory Crofts and Carol LaForge give a reader’s theater performance with the LaForge Encore Group as part of the festivities at the Luck of the Library community celebration held Monday. The celebration marked the extended library hours, which now includes Monday as well as the new self-checkout kiosks available for use by patrons. -

05357 HIP Newsltr Press.Indd

PARTICIPATION WINTER 2005 40th Anniversary for Hinckley Institute of Politics The Hinckley Institute of Politics will celebrate IN THIS ISSUE its 40th anniversary and announce the new director of the Hinckley Institute at an event in September. Institute History Page 2 The gathering will feature a prominent guest Scholarships Page 3 speaker and a program about the history of the Outstanding Interns Page 4 Institute. All former interns and students, commu- Congressional Interns Page 5 nity members, friends of the Institute, and elected Former Interns Page 5 officials are invited to attend. Further details will Featured Internships Page 6 be released in the coming months. We hope to see Hinckley News Page 6 you there! Semester Abroad Page 8 Hinckley Staff Page 9 Hinckley Forums Page 10 From top to bottom: Hinckley interns with newly elected 2003-2004 Interns Page 12 Utah Governor Jon Huntsman, Jr.; 1966 Hinckley Summer interns; intern Lieu Tran with Sen. Arlen Specter and Gov. Donors Page 15 Arnold Schwarzenegger; Pres. Ronald Reagan greeting Capital Encounter Page 16 interns; and Hinckley interns campaign for Scott Matheson, Jr. 1 HINCKLEY INSTITUTE OF POLITICS PARTICIPATION History of Hinckley Institute of Politics Scholarship Award Winners Anne Bergstedt Receives John Micah Elggren Receives Robert H. Hinckley founded the Hinckley Institute of Politics in 1965 with the vision to “teach students and Anne Hinckley Scholarship Robert H. Hinckley respect for practical politics and the principle of citizen involvement in government.” Forty years later, Mr. Hinckley’s dream is a reality. Countless students, schoolteachers, and the general public have participated in Graduate Scholarship programs he made possible through the Hinckley Institute. -

Lehi Historic Archive File Categories

Lehi Historic Archive File Categories Achievements of Lehi Citizens Adobe-Lehi Plant Advertisement-Baby Food Advertisement-Bells Advertisement-Bicycles Advertisement-Cameras Advertisement-Childrens Books Advertisement-China/Dishes/Table Settings Advertisement-Cook Ware Advertisement-Dolls Advertisement-Farm Equipment Advertisement-Flags Advertisement-Gardens/Tools/Equipment Advertisement-Groceries/Food Advertisement-Harps Advertisement-Horse and Buggies Advertisement-Kitchen Appliances Advertisement-Meats Advertisement-Medical Conditions Advertisement-Medical Hygiene Products Advertisement-Mens Clothing/Style Advertisement-Musical Instruments Advertisement-Pest Control Advertisement-Pianos Advertisement-Poems about Children Advertisement-Poultry-Chickens/Turkeys Advertisement-Railroads Advertisement-Rugs/Flooring Advertisement-Sewing Machines Advertisement-Silverware Advertisement-Socks/Hose Advertisement-Shoes Advertisement-Tiffanys Advertisement-Tires/Car Parts Advertisement-Travel Advertisement-Women’s Clothing/Style Airplane Flights in Lehi Airplanes-D4s Alex Christofferson-Champion Wrestler Alcohol All About Food and Fuel/Sinclair All Hallows College-Salt Lake Allred Park Alma Peterson Construction/Kent Peterson Alpine Draper Tunnel Alpine Fireplaces Alpine School Board-Andrew Fjeld Alpine School Board-Donna Barnes Alpine School Board-Kenneth Whimpey Alpine School Board-Thomas Powers Alpine School Board-William Samuel Evans Alpine School District Alpine Soil/Water Conservation District Alpine Stake Alpine Stake Tabernacle Alpine, -

Mar Apr 2019 FINAL.Pdf

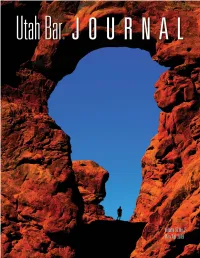

WONDERING WHAT ALL THE EXCITEMENT IS ABOUT? See our big announcement on page 33 801.366.9100 eckolaw.com The Utah Bar Journal Published by the Utah State Bar | 645 South 200 East, Salt Lake City, Utah 84111 | 801-531-9077 | www.utahbar.org BAR JOURNAL EDITORIAL BOARD Editor Utah Law Developments Editor Young Lawyer Representative William D. Holyoak LaShel Shaw Grace S. Pusavat Managing Editor Judicial Advisor Paralegal Representative Alisha Giles Judge Gregory K. Orme Greg Wayment Articles Editors Copy Editors Bar Staff Liaison Nicole G. Farrell Hal Armstrong Christine Critchley Lee Killian Paul Justensen Andrea Valenti Arthur Advertising/Design Manager Victoria Luman Editor at Large Laniece Roberts Todd Zagorec Departments Editor Judge Catherine E. Roberts (Ret.) MISSION & VISION OF THE BAR: The lawyers of the Utah State Bar serve the public and legal profession with excellence, civility, and integrity. We envision a just legal system that is understood, valued, and accessible to all. Cover Photo Turret Arch, by Utah State Bar member Lane Erickson. LANE ERICKSON is a partner at Racine Olson PLLP. Asked about his photo, Lane said, “I captured this image of the Turret Arch in Arches National Park a few years ago while on Spring Break with my family in Moab, Utah. The contrast of warm and cool colors between the red rock and the blue sky were striking, but what really caught my eye was the silhouette of the boy standing in the shadow of the Arch, because it provided scale showing how massive this incredible rock formation really is.” SUBMIT A COVER PHOTO Members of the Utah State Bar or Paralegal Division of the Bar who are interested in having photographs they have taken of Utah scenes published on the cover of the Utah Bar Journal should send their photographs (compact disk or print), along with a description of where the photographs were taken, to Utah Bar Journal, 645 South 200 East, Salt Lake City, Utah 84111, or by e-mail .jpg attachment to [email protected]. -

The Future of Higher Education

ANNUAL NEWSLETTER CONCEPTUAL RENDERING THE FUTURE OF HIGHER EDUCATION THE HINCKLEY INSTITUTE’S FUTURE HOME PLANNING FOR THE PRICE INTERNATIONAL PAVILION LAUNCH OF THE SAM RICH LECTURE SERIES MALCOLM GLADWELL’S VISION FOR COMPETITIVE STUDENTS OFFICE FOR GLOBAL ENGAGEMENT PARTNERSHIP THE U’S GLOBAL INTERNSHIPS POISED FOR MASSIVE GROWTH 2013 SICILIANO FORUM EDUCATION EXPERTS CONVERGE FOR FULL WEEK table of contents NEW & NOTEWORTHY: 4 HINCKLEY FELLOWS 5 DIGNITARIES 44 HINCKLEY HAPPENINGS: 8 HINCKLEY PRESENCE 10 HINCKLEY FORUMS 8 THE FUTURE OF HIGHER ED: 12 OUR VISION 14 PRICE INTERNATIONAL BUILDING 15 OUR NEW PARTNERSHIP 16 16 SICILIANO FORUM 18 SAM RICH LECTURE SERIES 1414 HINCKLEY TEAM: 20 OUR INTERNS 30 OUR STAFF 31 31 PORTRAIT UNVEILING Contributing Editors: Ellesse S. Balli Rochelle M. Parker Lisa Hawkins Kendahl Melvin Leo Masic Art Director: Ellesse S. Balli MESSAGE FROM THE DIRECTOR Malcolm Gladwell. Dubbed by the seven short years since we KIRK L. JOWERS Time magazine as “one of the 100 launched our global internship most influential people” in the program, we have placed more world and by Foreign Policy as than 400 students in almost 60 a leading “top global thinker,” countries across the globe. It is Gladwell discussed the advantages now celebrated as the best political of disadvantages in a sold-out and humanitarian internship pro- event at Abravanel Hall. gram in the U.S. Culminating this Gladwell’s findings confirmed achievement, this year the Hinck- my belief that it is far better for ley Institute was charged with undergraduates to be a “big fish” overseeing all University of Utah within the University of Utah and campus global internships in part- Hinckley Institute than a “little nership with the new Office for fish” at an Ivy League school. -

Qualitygrowthstrategy.Pdf

ENVISION UTAH QUALITY GROWTH STRATEGY AND TECHNICAL REVIEW January 2000 E NVISION U TAH •••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••• A Partnership for Quality Growth Keeping Utah Beautiful, Prosperous, and Neighborly for Future Generations Envision Utah • P.O. Box 30901 Salt Lake City, UT 84130 801-973-3307 www.envisionutah.org Sponsored by Coalition for Utah’s Future ENVISION UTAH Keeping Utah Beautiful, Prosperous, and Neighborly for Future Generations INTRODUCTION The urbanized area of Northern Utah is about state and local spending priorities. experiencing tremendous growth. The Greater Preparing for this growth also presents some Wasatch Area (GWA), which stretches from unique opportunities. For example, if we were Nephi to Brigham City, and from Kamas to able to reduce the size of average residential Grantsville, consists of 88 cities and towns, 10 lot from 0.35 acre to 0.29 acre, the total land counties, and numerous special service districts. area consumed by the next million people The GWA is currently home to 1.7 million would drop from 325 square miles of new land residents, who constitute 80% of the state’s to 154 square miles, and the amount of population, making Utah the sixth most urban agricultural land consumed by this growth state in the nation. The area’s developable private could drop from 143 square miles to just 27 land, which may total as little as 1000 square square miles. Thus, intensifying land uses miles, is surrounded by mountains, lakes, deserts, through infill in urbanized areas will ease the and public lands that form a natural growth pressure to develop new lands. boundary, within which nearly 370 square miles of A cost benefit analysis shows that if we adhere land is currently developed. -

Supreme Court of the United States ———— UTAH REPUBLICAN PARTY, Petitioner, V

No. 18-450 IN THE Supreme Court of the United States ———— UTAH REPUBLICAN PARTY, Petitioner, v. SPENCER J. COX, et al., Respondents. ———— On Petition for a Writ of Certiorari to the United States Court of Appeals for the Tenth Circuit ———— BRIEF OF AMICI CURIAE UTAH LEGISLATORS, CURRENT AND FORMER IN SUPPORT OF PETITIONER ———— LAURA EBERTING WILLIAM C. DUNCAN 2154 North 900 West Counsel of Record Pleasant Grove, UT 84062 1868 N 800 E (801) 592-5926 Lehi, UT 84043 [email protected] (801) 367-4570 [email protected] Counsel for Amici Curiae November 13, 2018 WILSON-EPES PRINTING CO., INC. – (202) 789-0096 – WASHINGTON, D. C. 20002 i QUESTION PRESENTED This brief will address the first question presented in the Petition, as follows: Does the First Amendment permit a government to compel a political party to use a state-preferred process for selecting a party’s standard-bearers for a general election, not to prevent discrimination or unfairness, but to alter the predicted viewpoints of those standard-bearers? ii TABLE OF CONTENTS QUESTION PRESENTED ......................................... i TABLE OF AUTHORITIES ..................................... iv INTEREST OF AMICI CURIAE ............................... 1 INTRODUCTION ...................................................... 1 STATEMENT ............................................................. 3 REASONS FOR GRANTING THE PETITION ........ 5 I. The Majority’s Holding Empowers Monied Special Interests and Invites Fraud. ................... 5 A. The group pushing to change the Party’s nominating process was built by local monied interests concerned that the process gave them too little power. .......... 5 B. The Party’s nominating system is a hurdle to buying influence. ............................. 9 1. The Party’s nominating system gives the average citizen an opportunity to play a larger role in politics.