Interview with Mira Schor

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Close Listening Mira Schor and Charles Bernstein August 23, 2009

COVER FEATURE Close Listening MIRA SCHOR AND CHARLES BERNSTEIN august 23, 2009 N PROVINCETOWN LAST SUMMER, poet Charles Bernstein interviewed Mira Schor for his Art Interna- tional Radio program, Close Listening. In the first of two half-hour programs, Schor read brief excerpts from several of her essays: “Figure/Ground” from Wet, and “Email to a Young Woman Artist,” “Recipe Art,” and “Modest Painting” from A Decade of Nega- tive Thinking. The original programs can be accessed at ARTonAIR.org and at PennSound (writing.upenn. Iedu/pennsound). ABOVE: MIRA SCHOR, 2009 PHOTO BY JULIA DAULT OPPOSITE: PROVINCETOWN STUDIO WALL, 2007 40 PROVINCETOWNARTS 2010 CHARLES BERNSTEIN: You started with a reading from the axiomatic, this critical oligarchy, to use your term, doesn’t exist your essay “Figure/Ground” from Wet and you brought anymore, nobody subscribes to that. Anybody who says that shouldn’t be listened to. We’ll have no part of them! We must exclude them! They up again this image of wet. You mentioned Duchamp as a are ignorant!” So exactly exemplifying the continuation by the denial, counterexample, but I don’t think Duchamp is really the dry which I think was quite funny. artist that is your target there. Could you revisit that for a Exactly. Whereas, in fact, they are incredibly well-trained clones of the second, coming back twenty years later? original. It’s like the Invasion of the Body Snatchers—they are clones. “We are not clones. We are independent thinkers.” [Here and MIRA SCHOR: I’m not sure that Duchamp requires defend- just below, Charles is speaking in the voice of a robot, or a person ing. -

Schor Moma Moma

12/12/2016 M/E/A/N/I/N/G: The Final Issue on A Year of Positive Thinking3 H O M E A B O U T L I N K S Browse: Home / 2016 / December / 09 / M/E/A/N/I/N/G: The Final Issue on A Year of Positive Thinking CONNE CT 3 Mira's Facebook Page DE CE MBE R 9 , 2 0 1 6 Subscribe in a Reader Subscribe by email M/E/A/N/I/N/G: The Final Issue on A Year of Positive Thinking3 miraschor.com The first issue of M/E/A/N/I/N/G: A Journal of Contemporary Art Issues, was published in December 1986. M/E/A/N/I/N/G is a collaboration between two artists, TAGS Susan Bee and Mira Schor, both painters with expanded interests in writing and 2016 election Abstract politics, and an extended community of artists, art critics, historians, theorists, and Expressionism ACTUAW poets, whom we sought to engage in discourse and to give a voice to. Activism Ana Mendieta Andrea For our 30th anniversary and final issue, we have asked some longtime contributors Geyer Andrea Mantegna Anselm and some new friends to create images and write about where they place meaning Kiefer Barack Obama CalArts craft today. As ever, we have encouraged artists and writers to feel free to speak to the Cubism DAvid Salle documentary concerns that have the most meaning to them right now. film drawing Edwin Denby Facebook feminism Every other day from December 5 until we are done, a grouping of contributions will Feminist art appear on A Year of Positive Thinking. -

Barbara-Zucker-CV-1.Pdf

Barbara Zucker Born, Philadelphia, PA. Lives and works in Burlington,Vermont, and New York, New York. Studio: 444 S. Union St. Burlington, Vermont 05401 802 863 8513 Fax: 802 864 5841 email: [email protected] Education University of Michigan, BS in Design Hunter College, MA Cranbrook Academy of Art Selected One Person Exhibitions Barbara Zucker: Time Signatures, The Gershman Y, Phila., Pa. 2007 Time Signatures: Tufts University, Mass., 2005 Universal Lines: Homage to Lilian Baker Carlisle and Other Women of Distinction”; Amy Tarrant Gallery, The Flynn Center for the Performing Arts, Burlington, Vt., 2001 Robert Hull Fleming Museum, Burlington, VT, 1998, 1980 One Great Jones Gallery, NYC, 1997 Paley Gallery, Moore College of Art, Phila., PA, 1996 (catalog) “For Beauty’s Sake,” Artists’ Space, NYC, 1994 Haeneh Kent Gallery, NYC, 1990 Webb and Parsons, Burlington, VT, 1989, 1991 Benjamin Mangel Gallery, Phila., PA, 1989 The Sculpture Center, NYC, April, 1989 Pam Adler Gallery, NYC, 1983, 1885 Swarthmore College, PA, 1983 Fine Arts Center, University of Massachusetts, Amherst, 1982 Joselyn Art Museum, Omaha, Nebraska, 1981 Robert Hull Fleming Museum, Burlington, VT, 1981 Robert Miller Gallery, NYC, 1978, 1980 Pennsylvania Academy of Fine Art, 1980 Marion Deson Gallery, Chicago, 1979, 1985 112 Greene Street Gallery, NYC, 1976 A.I.R. Gallery, NYC, 1972, 1974 Rutgers University, Douglass College, New Brunswick, NJ, 1973 Selected Group Exhibitions ‘Radical Lace and Subversive Knitting”, The Museum of Arts and Design, New York, 2007 “From the Inside Out: Feminist Art Then and Now”, New York, 2007 Winter Salon , Lesley Heller Gallery, December, New York, 2006 “Selfish“, curated by Lori Waxman, 128 Rivington, New York, 2004 Reading Between the Lines”, curated by Joyce Kozloff; Wooster Arts Space, New York, 2003 “Drawing Conclusions: Work by Artists Critics”, curated by Judith Collishan, New York Arts, New York, 2003 “The Art of Aging”, Hebrew Union College Museum, New York, 2003-2004; traveling exhibition, through 2006. -

13 Feminist Art Shows to See in Honor of Women's History Month

Exhibitions 13 Feminist Art Shows to See In Honor of Women’s History Month See these shows in New York and around the country, featuring women artists and feminist icons. Sarbani Ghosh, March 6, 2017 Susan Bee, Pow! (2014). Courtesy of A.I.R. Politics got you down? Grab back! March is Women’s History Month, and what better way to pay homage to all the pioneering women who have advanced the cause for women’s equality than to go see these 12 shows and exhibitions? Currently on view in New York and around the country, these shows feature the work of pioneering feminist artists, old and new: Vadis Turner, Black Nest , 2016. Photo Courtesy Equity Gallery and © Vadis Turner 1. “FemiNest” at Equity Gallery “FemiNest” brings together the works of Natalie Frank, Karen Lee Williams, Michele Oka Doner, Barbara Segal, Page Turner, and Vadis Turner around the idea of a “nest,” in both its literal and metaphorical meanings. The show explores new spaces for women, considering spirituality, materiality, societal behaviors in the domestic and non-domestic spheres, protection, and gender-specific production, via works in sculpture, textiles, painting, and many other media. Location: Equity Gallery, 245 Broome Street, New York Price: Free Date and time: Through March 25. Wednesday to Saturday, 12 p.m.–6 p.m., and by appointment. Yayoi Kusama’s Aftermath of Obliteration of Eternity. 2. “Yayoi Kusama: Infinity Mirrors” at the Hirshhorn Yayoi Kusama has been making headlines recently with her polka dots and pumpkins at the Hirshhorn Museum. Her “Happenings” in New York in the 1960s, where she explored the naked body as a stage for performance, were just the start of her rebellion against patriarchal systems of power. -

Mira Schor and Jason Andrew with PHONG BUI

ii BROOKLYNRAIL CRI ICA L PE:RSP CTIVES O N A RTS, PO LITICS, AN D CU LTU RE Art October 5th, 2009 INCONVERSATION Mira Schor and Jason Andrew WITH PHONG BUI On the occasion of the painter Jack Tworkov’s retrospective Against Extremes: Five Decades of Painting, which will be on view at The UBS Art Gallery until October 27, 2009, and the publication of The Extreme of the Middle: Writings of Jack Tworkov, published by Yale University Press, both curator, Jason Andrew, and editor, Mira Schor, paid a visit toOff the Rail Hour at Art International Radio to talk with Publisher Phong Bui about Tworkov’s life and work. Phong Bui (Rail): Having read the whole volume of writing and seen the show, I was struck by his incredibly astute observations which seemed to me must have derived from the capacity for self- criticism and self-analysis, and which gave him a sense of deliberate eloquence in his continuity as a painter and thinker. There are two things I remember reading from the book which really stayed with me: one is the first sentence from the journal entry, which he started right after the war, 1947, the same year as his first one-man show at Charles Egan Gallery, “Style is the effect of pressure. […] In the artist, the origin of pressure is in his total life—heredity, experience, and will […]—but the direction flows according to the freedom he allows his creative impulse.” Two is the long article “Notes on My Painting,” which was published in Art in America in 1973 under the invitation of Brian O’Doherty, where in the end he says, “Above all -

Proquest Dissertations

Redressing Femininity: Power and Pleasure in Dresses by Jana Sterbak and Cathy Daley by Catherine Ann Laird, B.Hum A thesis submitted to the Faculty of Graduate Studies and Research in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in Art History: Art and Its Institutions Carleton University OTTAWA, Ontario September, 2009 © 2009, Catherine Ann Laird Library and Archives Bibliothgque et 1*1 Canada Archives Canada Published Heritage Direction du Branch Patrimoine de l'6dition 395 Wellington Street 395, rue Wellington Ottawa ON K1A0N4 Ottawa ON K1A0N4 Canada Canada Your file Votre reference ISBN: 978-0-494-58451-4 Our file Notre r6f6rence ISBN: 978-0-494-58451-4 NOTICE: AVIS: The author has granted a non- L'auteur a accorde une licence non exclusive exclusive license allowing Library and permettant a la Bibliotheque et Archives Archives Canada to reproduce, Canada de reproduire, publier, archiver, publish, archive, preserve, conserve, sauvegarder, conserver, transmettre au public communicate to the public by par telecommunication ou par I'lnternet, preter, telecommunication or on the Internet, distribuer et vendre des theses partout dans le loan, distribute and sell theses monde, a des fins commerciales ou autres, sur worldwide, for commercial or non- support microforme, papier, electronique et/ou commercial purposes, in microform, autres formats. paper, electronic and/or any other formats. The author retains copyright L'auteur conserve la propriete du droit d'auteur ownership and moral rights in this et des droits moraux qui protege cette these. Ni thesis. Neither the thesis nor la these ni des extraits substantiels de celle-ci substantial extracts from it may be ne doivent etre imprimes ou autrement printed or otherwise reproduced reproduits sans son autorisation. -

Paintings by Susan Bee and Miriam Laufer, AIR Gallery, NY, 2006

SUSAN BEE E-mail: [email protected] Website: http://epc.buffalo.edu/authors/bee/ SELECTED EXHIBITIONS Solo Shows Seeing Double: Paintings by Susan Bee and Miriam Laufer, A.I.R. Gallery, NY, 2006 (catalogue with essay by Johanna Drucker) Sign Under Test: Paintings and Artist’s Books, Pacific Switchboard Art Space, Portland, Oregon, 2004 Miss Dynamite: New Paintings, A.I.R. Gallery, New York, 2003 Miss Dynamite and Other Tales, Olin Art Gallery, Kenyon College, Gambier, Ohio, 2002 Ice Cream Sunday: Paintings and Works on Paper, Ben Shahn Galleries at William Paterson University of New Jersey, 2001 (catalogue with essay by David Shapiro) New Work, Rare Books and Manuscript Library, School of International Affairs, Columbia University, New York, 2000 Beware the Lady: New Paintings and Works on Paper, A.I.R. Gallery, New York, 2000 (catalogue with essay by John Yau) Touchdown, Recent Paintings, Cornershop Gallery, Buffalo, 1999 Post-Americana: New Paintings, A.I.R. Gallery, New York, 1998 Recent Paintings and a New Artist's Book, Granary Books Gallery, New York, 1997 New Paintings, Virginia Lust Gallery, New York, 1992 Altered Photo Images, Jack Morris Gallery, New York, 1979 Solo Show, Office of the Graduate School, Columbia University, New York, 1972 Selected Group Shows One True Thing, A.I.R. Gallery, NY; Putney School, VT, 2007 Pink Kid Gloves, Chashama Gallery, NY, 2006 Complicit! Contemporary American Art and Mass Culture, University of Virginia Art Museum, Charlottesville, VA, 2006 Conceptual Comics, Banff Centre for the Arts, Alberta, Canada, 2006 Generations, A.I.R. Gallery, NY, 1997, 2002, 2004, 2006 Too Much Bliss: Twenty Years of Granary Books, Smith College Museum, MA, 2005-06 I.D.:id; Wish You Were Here IV, A.I.R. -

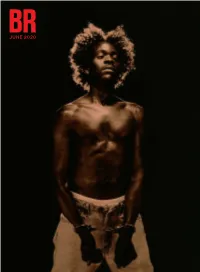

June 2020 June 2020 June 2020 June 2020

JUNE 2020 JUNE 2020 JUNE 2020 JUNE 2020 field notes art books Normality is Death by Jacob Blumenfeld 6 Greta Rainbow on Joel Sternfeld’s American Prospects 88 Where Is She? by Soledad Álvarez Velasco 7 Kate Silzer on Excerpts from the1971 Journal of Prison in the Virus Time by Keith “Malik” Washington 10 Rosemary Mayer 88 Higher Education and the Remaking of the Working Class Megan N. Liberty on Dayanita Singh’s by Gary Roth 11 Zakir Hussain Maquette 89 The pandemics of interpretation by John W. W. Zeiser 15 Jennie Waldow on The Outwardness of Art: Selected Writings of Adrian Stokes 90 Propaganda and Mutual Aid in the time of COVID-19 by Andreas Petrossiants 17 Class Power on Zero-Hours by Jarrod Shanahan 19 books Weston Cutter on Emily Nemens’s The Cactus League art and Luke Geddes’s Heart of Junk 91 John Domini on Joyelle McSweeney’s Toxicon and Arachne ART IN CONVERSATION and Rachel Eliza Griffiths’s Seeing the Body: Poems 92 LYLE ASHTON HARRIS with McKenzie Wark 22 Yvonne C. Garrett on Camille A. Collins’s ART IN CONVERSATION The Exene Chronicles 93 LAUREN BON with Phong H. Bui 28 Yvonne C. Garrett on Kathy Valentine’s All I Ever Wanted 93 ART IN CONVERSATION JOHN ELDERFIELD with Terry Winters 36 IN CONVERSATION Jason Schneiderman with Tony Leuzzi 94 ART IN CONVERSATION MINJUNG KIM with Helen Lee 46 Joseph Peschel on Lily Tuck’s Heathcliff Redux: A Novella and Stories 96 june 2020 THE MUSEUM DIRECTORS PENNY ARCADE with Nick Bennett 52 IN CONVERSATION Ben Tanzer with Five Debut Authors 97 IN CONVERSATION Nick Flynn with Elizabeth Trundle 100 critics page IN CONVERSATION Clifford Thompson with David Winner 102 TOM MCGLYNN The Mirror Displaced: Artists Writing on Art 58 music David Rhodes: An Artist Writing 60 IN CONVERSATION Keith Rowe with Todd B. -

Feminist Art Education: Made in California

Feminist Art Education: Made in California by Judy Chicago ’ve often stated that it I thought that if my situation was similar to Iwould have been im- that of other women, then perhaps my strug- possible to conceive of, gle might serve as a model for the struggle much less implement, the out of gendered conditioning that a woman 1970/71 Fresno Feminist would have to make if she were to realize Art Program anywhere but herself artistically. I was sure that this process California. One reason for would take some time. Therefore, I set up the this became evident in the Fresno program with the idea that I would 2000 Los Angeles County work intensely with the fifteen women I chose Museum of Art exhibit on as students. 100 years of art in Califor- nia, whose title I borrowed It’s important to take a moment to comment for this chapter. The Made on the climate for women at that time. There in California show demon- were no Women’s Studies courses, nor any un- strated some of the unique derstanding that women had their own his- qualities of California cul- tory. In fact, attitudes might be best under- ture, notably, an open- stood through the story of a class in European ness to new ideas that is Intellectual History I had taken in the early less prominently found in 1960s, while I was an undergraduate at UCLA. the East, where the white, At the first class meeting, the professor said male, Eurocentric tradi- he would talk about women’s contributions tion has a longer legacy at the end of the semester. -

The Screen As a Site of Division and Encounter

This work has been submitted to NECTAR, the Northampton Electronic Collection of Theses and Research. Thesis Title: The screen as a site of division and encounter Creators: Marchevska, E. Example citation: Marchevska, E. (2012) The screen as a site ofR division and encounter. Doctoral thesis. The University of NorthampAton. Version: Accepted version http://nectarC.northampTton.ac.uk/6130/ NE The screen as a site of division and encounter Submitted for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy At the University of Northampton Year 2012 Elena Marchevska © Elena Marchevska, 20th of November, 2012. This thesis is copyright material and no quotation from it may be published without proper acknowledgement. 1 Contents ACKNOWLEDGMENTS ............................................................................................. 5 PRELUDE OR HOW TO READ THIS THESIS ........................................................... 7 THE SCREEN, THE PAGE, THE WINDOW ............................................................. 12 Diary entry, Day 4 ........................................................................................................................ 15 1.1 . RESEARCH STRATEGY ....................................................................................................... 15 1.1.1. Practice as research ......................................................................................... 16 1.1.2. Field review (contextual analysis) ..................................................................... 18 1.1.3. Performative reflective -

The Brooklyn Rail.”

ART IN CONVERSATION 18 ART IN CONVERSATION ART IN CONVERSATION SUSAN BEE: It was published for 10 years as a printed journal: 1986-1996, then online till 2016. SUSAN BEE We also did M/E/A/N/I/N/G: An Anthology of Artists’ Writings, Theory, and Criticism, pub- lished by Duke University Press in 2000, and then in December 2016 after Trump won, we did our with Phong H. Bui final online issue, #7. We just thought “Ok, we’ve had our say and we’re passing the baton to you guys, the Brooklyn Rail.” RAIL: Whaaat! [Laughter] Thank you so much. Although I was first aware of the essential Before I start I would like to bring up different insightful observations that were written by M/E/A/N/I/N/G in the early 1990s, a biannual pub- Raphael Rubinstein, David Shapiro, Johanna Drucker, among others. Raphael thought, for lication focusing on issues of feminism and painting example, that your work lies in between the famil- from various dissenting perspectives (edited by Susan iar and the strange, which manifests in the use of material and images. David Shapiro referred Bee and Mira Schor, published between 1986 and 1996 to your sense of humor in how you seem to be carelessly or anachronistically playful with your in print, and online from 2001 to 2016), it was only repertoire of images, and how to compose them later that I met the painter Susan Bee through the late and whatnot. You thrive in the idea of painting the space between the figures and the objects. -

Feminism Reframed

Feminism Reframed Feminism Reframed Edited by Alexandra M. Kokoli Cambridge Scholars Publishing Feminism Reframed, Edited by Alexandra M. Kokoli This book first published 2008 by Cambridge Scholars Publishing 15 Angerton Gardens, Newcastle, NE5 2JA, UK British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library Copyright © 2008 by Alexandra M. Kokoli and contributors All rights for this book reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior permission of the copyright owner. ISBN (10): 1-84718-405-7, ISBN (13): 9781847184054 TABLE OF CONTENTS Introduction ................................................................................................. 1 Looking On, Bouncing Back Alexandra M. Kokoli Section I: On Exhibition(s): Institutions, Curatorship, Representation Chapter One............................................................................................... 20 Women Artists, Feminism and the Museum: Beyond the Blockbuster Retrospective Joanne Heath Chapter Two.............................................................................................. 41 Why Have There Been No Great Women Dadaists? Ruth Hemus Chapter Three............................................................................................ 61 “Draws Like a Girl”: The Necessity of Old-School Feminist Interventions in the World of Comics