Feminism Reframed

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Schor Moma Moma

12/12/2016 M/E/A/N/I/N/G: The Final Issue on A Year of Positive Thinking3 H O M E A B O U T L I N K S Browse: Home / 2016 / December / 09 / M/E/A/N/I/N/G: The Final Issue on A Year of Positive Thinking CONNE CT 3 Mira's Facebook Page DE CE MBE R 9 , 2 0 1 6 Subscribe in a Reader Subscribe by email M/E/A/N/I/N/G: The Final Issue on A Year of Positive Thinking3 miraschor.com The first issue of M/E/A/N/I/N/G: A Journal of Contemporary Art Issues, was published in December 1986. M/E/A/N/I/N/G is a collaboration between two artists, TAGS Susan Bee and Mira Schor, both painters with expanded interests in writing and 2016 election Abstract politics, and an extended community of artists, art critics, historians, theorists, and Expressionism ACTUAW poets, whom we sought to engage in discourse and to give a voice to. Activism Ana Mendieta Andrea For our 30th anniversary and final issue, we have asked some longtime contributors Geyer Andrea Mantegna Anselm and some new friends to create images and write about where they place meaning Kiefer Barack Obama CalArts craft today. As ever, we have encouraged artists and writers to feel free to speak to the Cubism DAvid Salle documentary concerns that have the most meaning to them right now. film drawing Edwin Denby Facebook feminism Every other day from December 5 until we are done, a grouping of contributions will Feminist art appear on A Year of Positive Thinking. -

Barbara-Zucker-CV-1.Pdf

Barbara Zucker Born, Philadelphia, PA. Lives and works in Burlington,Vermont, and New York, New York. Studio: 444 S. Union St. Burlington, Vermont 05401 802 863 8513 Fax: 802 864 5841 email: [email protected] Education University of Michigan, BS in Design Hunter College, MA Cranbrook Academy of Art Selected One Person Exhibitions Barbara Zucker: Time Signatures, The Gershman Y, Phila., Pa. 2007 Time Signatures: Tufts University, Mass., 2005 Universal Lines: Homage to Lilian Baker Carlisle and Other Women of Distinction”; Amy Tarrant Gallery, The Flynn Center for the Performing Arts, Burlington, Vt., 2001 Robert Hull Fleming Museum, Burlington, VT, 1998, 1980 One Great Jones Gallery, NYC, 1997 Paley Gallery, Moore College of Art, Phila., PA, 1996 (catalog) “For Beauty’s Sake,” Artists’ Space, NYC, 1994 Haeneh Kent Gallery, NYC, 1990 Webb and Parsons, Burlington, VT, 1989, 1991 Benjamin Mangel Gallery, Phila., PA, 1989 The Sculpture Center, NYC, April, 1989 Pam Adler Gallery, NYC, 1983, 1885 Swarthmore College, PA, 1983 Fine Arts Center, University of Massachusetts, Amherst, 1982 Joselyn Art Museum, Omaha, Nebraska, 1981 Robert Hull Fleming Museum, Burlington, VT, 1981 Robert Miller Gallery, NYC, 1978, 1980 Pennsylvania Academy of Fine Art, 1980 Marion Deson Gallery, Chicago, 1979, 1985 112 Greene Street Gallery, NYC, 1976 A.I.R. Gallery, NYC, 1972, 1974 Rutgers University, Douglass College, New Brunswick, NJ, 1973 Selected Group Exhibitions ‘Radical Lace and Subversive Knitting”, The Museum of Arts and Design, New York, 2007 “From the Inside Out: Feminist Art Then and Now”, New York, 2007 Winter Salon , Lesley Heller Gallery, December, New York, 2006 “Selfish“, curated by Lori Waxman, 128 Rivington, New York, 2004 Reading Between the Lines”, curated by Joyce Kozloff; Wooster Arts Space, New York, 2003 “Drawing Conclusions: Work by Artists Critics”, curated by Judith Collishan, New York Arts, New York, 2003 “The Art of Aging”, Hebrew Union College Museum, New York, 2003-2004; traveling exhibition, through 2006. -

13 Feminist Art Shows to See in Honor of Women's History Month

Exhibitions 13 Feminist Art Shows to See In Honor of Women’s History Month See these shows in New York and around the country, featuring women artists and feminist icons. Sarbani Ghosh, March 6, 2017 Susan Bee, Pow! (2014). Courtesy of A.I.R. Politics got you down? Grab back! March is Women’s History Month, and what better way to pay homage to all the pioneering women who have advanced the cause for women’s equality than to go see these 12 shows and exhibitions? Currently on view in New York and around the country, these shows feature the work of pioneering feminist artists, old and new: Vadis Turner, Black Nest , 2016. Photo Courtesy Equity Gallery and © Vadis Turner 1. “FemiNest” at Equity Gallery “FemiNest” brings together the works of Natalie Frank, Karen Lee Williams, Michele Oka Doner, Barbara Segal, Page Turner, and Vadis Turner around the idea of a “nest,” in both its literal and metaphorical meanings. The show explores new spaces for women, considering spirituality, materiality, societal behaviors in the domestic and non-domestic spheres, protection, and gender-specific production, via works in sculpture, textiles, painting, and many other media. Location: Equity Gallery, 245 Broome Street, New York Price: Free Date and time: Through March 25. Wednesday to Saturday, 12 p.m.–6 p.m., and by appointment. Yayoi Kusama’s Aftermath of Obliteration of Eternity. 2. “Yayoi Kusama: Infinity Mirrors” at the Hirshhorn Yayoi Kusama has been making headlines recently with her polka dots and pumpkins at the Hirshhorn Museum. Her “Happenings” in New York in the 1960s, where she explored the naked body as a stage for performance, were just the start of her rebellion against patriarchal systems of power. -

Paintings by Susan Bee and Miriam Laufer, AIR Gallery, NY, 2006

SUSAN BEE E-mail: [email protected] Website: http://epc.buffalo.edu/authors/bee/ SELECTED EXHIBITIONS Solo Shows Seeing Double: Paintings by Susan Bee and Miriam Laufer, A.I.R. Gallery, NY, 2006 (catalogue with essay by Johanna Drucker) Sign Under Test: Paintings and Artist’s Books, Pacific Switchboard Art Space, Portland, Oregon, 2004 Miss Dynamite: New Paintings, A.I.R. Gallery, New York, 2003 Miss Dynamite and Other Tales, Olin Art Gallery, Kenyon College, Gambier, Ohio, 2002 Ice Cream Sunday: Paintings and Works on Paper, Ben Shahn Galleries at William Paterson University of New Jersey, 2001 (catalogue with essay by David Shapiro) New Work, Rare Books and Manuscript Library, School of International Affairs, Columbia University, New York, 2000 Beware the Lady: New Paintings and Works on Paper, A.I.R. Gallery, New York, 2000 (catalogue with essay by John Yau) Touchdown, Recent Paintings, Cornershop Gallery, Buffalo, 1999 Post-Americana: New Paintings, A.I.R. Gallery, New York, 1998 Recent Paintings and a New Artist's Book, Granary Books Gallery, New York, 1997 New Paintings, Virginia Lust Gallery, New York, 1992 Altered Photo Images, Jack Morris Gallery, New York, 1979 Solo Show, Office of the Graduate School, Columbia University, New York, 1972 Selected Group Shows One True Thing, A.I.R. Gallery, NY; Putney School, VT, 2007 Pink Kid Gloves, Chashama Gallery, NY, 2006 Complicit! Contemporary American Art and Mass Culture, University of Virginia Art Museum, Charlottesville, VA, 2006 Conceptual Comics, Banff Centre for the Arts, Alberta, Canada, 2006 Generations, A.I.R. Gallery, NY, 1997, 2002, 2004, 2006 Too Much Bliss: Twenty Years of Granary Books, Smith College Museum, MA, 2005-06 I.D.:id; Wish You Were Here IV, A.I.R. -

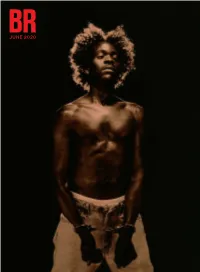

June 2020 June 2020 June 2020 June 2020

JUNE 2020 JUNE 2020 JUNE 2020 JUNE 2020 field notes art books Normality is Death by Jacob Blumenfeld 6 Greta Rainbow on Joel Sternfeld’s American Prospects 88 Where Is She? by Soledad Álvarez Velasco 7 Kate Silzer on Excerpts from the1971 Journal of Prison in the Virus Time by Keith “Malik” Washington 10 Rosemary Mayer 88 Higher Education and the Remaking of the Working Class Megan N. Liberty on Dayanita Singh’s by Gary Roth 11 Zakir Hussain Maquette 89 The pandemics of interpretation by John W. W. Zeiser 15 Jennie Waldow on The Outwardness of Art: Selected Writings of Adrian Stokes 90 Propaganda and Mutual Aid in the time of COVID-19 by Andreas Petrossiants 17 Class Power on Zero-Hours by Jarrod Shanahan 19 books Weston Cutter on Emily Nemens’s The Cactus League art and Luke Geddes’s Heart of Junk 91 John Domini on Joyelle McSweeney’s Toxicon and Arachne ART IN CONVERSATION and Rachel Eliza Griffiths’s Seeing the Body: Poems 92 LYLE ASHTON HARRIS with McKenzie Wark 22 Yvonne C. Garrett on Camille A. Collins’s ART IN CONVERSATION The Exene Chronicles 93 LAUREN BON with Phong H. Bui 28 Yvonne C. Garrett on Kathy Valentine’s All I Ever Wanted 93 ART IN CONVERSATION JOHN ELDERFIELD with Terry Winters 36 IN CONVERSATION Jason Schneiderman with Tony Leuzzi 94 ART IN CONVERSATION MINJUNG KIM with Helen Lee 46 Joseph Peschel on Lily Tuck’s Heathcliff Redux: A Novella and Stories 96 june 2020 THE MUSEUM DIRECTORS PENNY ARCADE with Nick Bennett 52 IN CONVERSATION Ben Tanzer with Five Debut Authors 97 IN CONVERSATION Nick Flynn with Elizabeth Trundle 100 critics page IN CONVERSATION Clifford Thompson with David Winner 102 TOM MCGLYNN The Mirror Displaced: Artists Writing on Art 58 music David Rhodes: An Artist Writing 60 IN CONVERSATION Keith Rowe with Todd B. -

The Brooklyn Rail.”

ART IN CONVERSATION 18 ART IN CONVERSATION ART IN CONVERSATION SUSAN BEE: It was published for 10 years as a printed journal: 1986-1996, then online till 2016. SUSAN BEE We also did M/E/A/N/I/N/G: An Anthology of Artists’ Writings, Theory, and Criticism, pub- lished by Duke University Press in 2000, and then in December 2016 after Trump won, we did our with Phong H. Bui final online issue, #7. We just thought “Ok, we’ve had our say and we’re passing the baton to you guys, the Brooklyn Rail.” RAIL: Whaaat! [Laughter] Thank you so much. Although I was first aware of the essential Before I start I would like to bring up different insightful observations that were written by M/E/A/N/I/N/G in the early 1990s, a biannual pub- Raphael Rubinstein, David Shapiro, Johanna Drucker, among others. Raphael thought, for lication focusing on issues of feminism and painting example, that your work lies in between the famil- from various dissenting perspectives (edited by Susan iar and the strange, which manifests in the use of material and images. David Shapiro referred Bee and Mira Schor, published between 1986 and 1996 to your sense of humor in how you seem to be carelessly or anachronistically playful with your in print, and online from 2001 to 2016), it was only repertoire of images, and how to compose them later that I met the painter Susan Bee through the late and whatnot. You thrive in the idea of painting the space between the figures and the objects. -

Artist Writings: Critical Essays, Reception, and Conditions of Production Since the 60S

Artist Writings: Critical Essays, Reception, and Conditions of Production since the 60s by Leanne Katherine Carroll A thesis submitted in conformity with the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy—History of Art Department of Art University of Toronto © Copyright by Leanne Katherine Carroll 2013 Artist Writings: Critical Essays, Reception, and Conditions of Production since the 60s Leanne Carroll Doctor of Philosophy—History of Art Department of Art University of Toronto 2013 Abstract This dissertation uncovers the history of what is today generally accepted in the art world, that artists are also artist-writers. I analyse a shift from writing by artists as an ostensible aberration to artist writing as practice. My structuring methodology is assessing artist writings and their conditions and reception in their moment of production and in their singularity. In Part 1, I argue that, while the Abstract-Expressionist artist-writers were negatively received, a number of AbEx- inflected conditions influenced and made manifest the valuing of artist writings. I demonstrate that Donald Judd conceived of writing as stemming from the same methods and responsibilities of the artist—following the guiding principle that art comes from art, from taking into account developments of the recent past—and as an essayistic means to argumentatively air his extra-art concerns; that writing for Dan Graham was an art world right of entry; and that Robert Smithson treated words as primary substances in a way that complicates meaning in his articles and in his objects and earthworks, in the process introducing a modernist truth to materials that gave the writing cachet while also serving as the basis for its domestication. -

Guide to the Colin De Land and Pat Hearn Library Collection MSS.012 Hannah Mandel; Collection Processed by Ann Butler, Ryan Evans and Hannah Mandel

CCS Bard Archives Phone: 845.758.7567 Center for Curatorial Studies Fax: 845.758.2442 Bard College Email: [email protected] Annandale-on-Hudson, NY 12504 Guide to the Colin de Land and Pat Hearn Library Collection MSS.012 Hannah Mandel; Collection processed by Ann Butler, Ryan Evans and Hannah Mandel. This finding aid was produced using ArchivesSpace on February 06, 2019 . Describing Archives: A Content Standard Guide to the Colin de Land and Pat Hearn Library Collection MSS.012 Table of Contents Summary Information ................................................................................................................................................ 3 Biographical / Historical ............................................................................................................................................. 5 Scope and Contents ................................................................................................................................................. 6 Arrangement .............................................................................................................................................................. 6 Administrative Information ......................................................................................................................................... 7 Related Materials ...................................................................................................................................................... 7 Controlled Access Headings .................................................................................................................................... -

Interview with Mira Schor

Mobile Fidelities Conversations on Feminism, History and Visuality Martina Pachmanová M. Pachmanová Mobile Fidelities n.paradoxa online issue no.19 May 2006 ISSN: 1462-0426 1 Published in English as an online edition by KT press, www.ktpress.co.uk, as issue 19, n.paradoxa: international feminist art journal http://www.ktpress.co.uk/pdf/nparadoxaissue19.pdf e-book available at www.ktpress.co.uk/pdf/mpachmanova.pdf July 2006, republished in this form: January 2010 ISSN: 1462-0426 ISBN: 0-9536541-1-7 e-book ISBN 13: 978-0-9536541-1-6 First published in Czech as Vernost v pohybu Prague: One Woman Press, 2001 ISBN: 80-86356-10-8 Chapter III. Kaya Silverman ‘The World Wants Your Desire’ was first published in English in n.paradoxa: international feminist art journal (print) Vol. 6 July 2000 pp.5-11 M. Pachmanová Mobile Fidelities n.paradoxa online issue no.19 May 2006 ISSN: 1462-0426 2 List of Contents Martina Pachmanová Introduction 4 Art History and Historiography I. Linda NochlinNochlin: Writing History “Otherly” 14 II. Natalie Boymel KampenKampen: Calling History Writing into Question 22 Subjectivity and Identity III. Kaja SilvermanSilverman: The World Wants Your Desire 30 IV. Susan Rubin SuleimanSuleiman: Subjectivity In Flux 41 Aesthetics and Sexual Politics V. Amelia JonesJones: Art’s Sexual Politics 53 VI. Mira SchorSchor: Painterly and Critical Pleasures 65 VII. Jo Anna IsaakIsaak: Ripping Off the Emperor’s Clothes 78 Society and the Public Sphere VIII.Janet WolffWolff: Strategies of Correction and Interrogation 86 IX. Martha RoslerRosler: Subverting the Myths of Everyday Life 98 Art Institutions X. -

Long Essay Assignment

Long Essay Assignment Modern Art Survey, 1900 - 1970s Write your essay, 8 – 10 pages, on the work and its significance on one of the following artists: Berenice Abbott Dorthea Rockburne Evelyn Cheston Rita Letendre Carrie Mae Weems Blanche & Yvonne Bolduc Louise Bourgoise Aloise Jacqueline Marval Anne Savage Yuriko Yamaguchi Marisol Ethel Seath Kathe Kollowitz Wanda Gag Audrey Flack Ghisha Koenig Elisabeth Collins Jacobine Jones Georgia O’Keefe Stanislawa de Karlowska Florence Wyle Martha Rosler Miriam Shapiro Vanessa Bell Tina Mondotti Pitseolak Ashoona Mary Cassatt Yayoi Kusama Leonor Fini Pitseloak Ashoona Evelyn Gibbs Harmony Hammond Sonia Delauney Sylvia Melland Laura Muntz Lyall Alice Barber Stevens Gertrude Abercrombie Dod Procter Francesca Woodman Jessica Dismorr Frances Anne Hopkins Doris McCarthy Dorothy Stevens Jeanne Mammen Laura Knight Esther Warkov Paraskeva Clark Ethel Walker Elizabeth Wyn Wood Mary Pratt Frances Hodgkins Anne Meredith Barry Paula Modersohn Becker Marian Scott Marion Tuu`Luuq Kenojuak Ashevak Anne Kahane Grace Albee Diane Arbus Janet Kigusiuq Marion Nicol Cecilia Beaux Marie Laurecin Suzanne Rivard Le Moyne Christine Pflug Janet Mitchell Dorothy Dehner Kim Lim Agnes Denes Mary Potter Joyce Wieland Dottie Attie Evelyn Mary Dunbar Alice Bailly Shizueye Takashima Marie Bashkirtseff Leonora Carrington Florence Vale Emily Carr Audrey Flack Faith Ringgold Jessie Oonark Lois Mailou Jones Louise Nevelson Isabel McLaughlin Annie Swynnerton Elaine Fried de Kooning Rita Ling Tamara De Lempicka Grace Hartigan Djuna -

JOANNA FRUEH Contact: [email protected] Website Joannafrueh.Com the Joanna Frueh Personal Archive Is at Stanford Librari

JOANNA FRUEH contact: [email protected] website joannafrueh.com The Joanna Frueh personal archive is at Stanford Libraries. EDUCATION University of Chicago, Chicago, IL, Ph.D. in History of Culture, 1981 Doctoral Dissertation: The Rossetti Woman University of Chicago, Chicago, IL, M.A. in General Studies in the Humanities, 1971 Masters Thesis: The Sphinx in the Nineteenth Century Sarah Lawrence College, B.A., Bronxville, NY, 1970 Concentration in Art History and English AWARDS, GRANTS, FELLOWSHIPS Lifetime Achievement Award, Women’s Caucus for Art, 2008 Nevada Arts Council Artist Fellowship in Literary Arts for Nonfiction, Honorable Mention, 2006 Dean’s Award for Research and Creative Activity, University of Nevada, Reno. 2006. For career achievements. Creative Activity Fund, School of the Arts, University of Nevada, Reno, 2005. For color reproductions in Clairvoyance (For Those In The Desert), Duke University Press, 2008. Nevada Arts Council Jackpot Grant, 2004. For the production of the book Joanna Frueh: A Retrospective. Nevada Arts Council Artist Fellowship in Literary Arts for Nonfiction, 2001 Susan Koppelman Award for Picturing the Modern Amazon, 2001 For best anthology, multi-authored or –edited Feminist Studies in Popular and/or American Culture. Given by the Women’s Caucus for the Popular and American Culture Associations. Nevada Arts Council Mini-Grant, 1994. For documenting my performance Pythia. Alan Bible Teaching Excellence Award (Runner-up), 1993. College of Arts and Science, University of Nevada, Reno Junior Faculty Research Award, University of Nevada, Reno, 1992. Project: Women Artists and Aging Susan Koppelman Award for Feminist Art Criticism: An Anthology, 1989. For best anthology, multi- authored or -edited Feminist Studies in Popular and/or American Culture. -

VALENTINE "There Are No Facts, Only Interpretations." —Frederich Nietzche

134 Guest Editor: Peggy Cyphers CONTRIBUTORS Suzanne Anker Terra Keck Katherine Bowling KK Kozik Amanda Church Marilyn Lerner Nicolle Cohen Jill Levine Elizabeth Condon Linda Levit Ford Crull Judith Linhares Peggy Cyphers Pam Longobardi Steve Dalachinsky Darwin C. Manning Dan Devine Michael McKenzie Debra Drexler Maureen McQuillan Emily Feinstein Stephen Paul Miller Jane Fire Lucio Pozzi RM Fischer Archie Rand Kathy Goodell James Romberger Julie Heffernan Christy Rupp David Humphrey Mira Schor Judith Simonian Lawre Stone Jeffrey C. Wright Brenda Zlamany VALENTINE "There are no facts, only interpretations." —Frederich Nietzche “When the power of love overcomes the love of power, the world will know peace.” —Jimi Hendrix JEFFREY C. WRIGHT Feathered Flower PEGGY CYPHERS Heirs to the Sea RED SCREEN Silvio Wolf 134 JILL LEVINE Euphorico Copyright © 2020, Marina Urbach Holger Drees Mignon Nixon Lisa Zwerling New Observations Ltd. George Waterman Lloyd Dunn Valery Oisteanu and the authors. Phillip Evans-Clark Wyatt Osato Back issues may be All rights reserved. Legal Advisors FaGaGaGa: Mark & Saul Ostrow purchased at: ISSN #0737-5387 Paul Hastings, LLP Mel Corroto Stephen Paul Miller Printed Matter Inc. Frank Fantauzzi Pedro A.H. Paixão 231 Eleventh Avenue Publisher Past Guest Editors Jim Feast Gilberto Perez New York, NY 10001 Mia Feroleto Keith Adams Mia Feroleto Stephen Perkins Richard Armijo Elizabeth Ferrer Bruno Pinto To pre-order or support Guest Editor Christine Armstrong Jane Fire Adrian Piper please send check or Peggy Cyphers Stafford Ashani Steve Flanagan Leah Poller money order to: Karen Atkinson Roland Flexner Lucio Pozzi New Observations VALENTINE Graphic Designer Todd Ayoung Stjepan G.