THE UNIVERSITY of HULL Transition Stories

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Libertarian Marxism Mao-Spontex Open Marxism Popular Assembly Sovereign Citizen Movement Spontaneism Sui Iuris

Autonomist Marxist Theory and Practice in the Current Crisis Brian Marks1 University of Arizona School of Geography and Development [email protected] Abstract Autonomist Marxism is a political tendency premised on the autonomy of the proletariat. Working class autonomy is manifested in the self-activity of the working class independent of formal organizations and representations, the multiplicity of forms that struggles take, and the role of class composition in shaping the overall balance of power in capitalist societies, not least in the relationship of class struggles to the character of capitalist crises. Class composition analysis is applied here to narrate the recent history of capitalism leading up to the current crisis, giving particular attention to China and the United States. A global wave of struggles in the mid-2000s was constituitive of the kinds of working class responses to the crisis that unfolded in 2008-10. The circulation of those struggles and resultant trends of recomposition and/or decomposition are argued to be important factors in the balance of political forces across the varied geography of the present crisis. The whirlwind of crises and the autonomist perspective The whirlwind of crises (Marks, 2010) that swept the world in 2008, financial panic upon food crisis upon energy shock upon inflationary spiral, receded temporarily only to surge forward again, leaving us in a turbulent world, full of possibility and peril. Is this the end of Neoliberalism or its retrenchment? A new 1 Published under the Creative Commons licence: Attribution-Noncommercial-No Derivative Works Autonomist Marxist Theory and Practice in the Current Crisis 468 New Deal or a new Great Depression? The end of American hegemony or the rise of an “imperialism with Chinese characteristics?” Or all of those at once? This paper brings the political tendency known as autonomist Marxism (H. -

Segmentet Rrugore Të Parashikuara Nga Bashkitë Për

SEGMENTET RRUGORE TË PARASHKIKUARA NGA BASHKITE PËR RIKONSTRUKSION/SISTEMIM NË PLANIN E BUXHETIT 2018 BASHKIA TIRANË Rehabilitimi Sheshi 1 “Kont Urani” Rehabilitimi Sheshi 2 Kafe “Flora” Rehabilitimi Sheshi 3 Blloku “Partizani” Rehabilitimi Sheshi 4 Sheshi “Çajupi” Rehabilitimi Sheshi 5 Stadiumi “Selman Stermasi” Rehabilitimi Sheshi 6 Perballe shkollës “Besnik Sykja” Rehabilitimi Sheshi 7 Pranë “Selvisë” Rehabilitimi Sheshi 8 “Medreseja” Rehabilitimi Sheshi 9 pranë tregut Industrial Rehabilitimi Sheshi 10 Laprakë Rehabilitimi Sheshi 11 Sheshi “Kashar” Rikonstruksioni i rruges Mihal Grameno dhe degezimit te rruges Budi - Depo e ujit (faza e dyte) Ndertim i rruges "Danish Jukniu" Rikonstruksioni i Infrastruktures sebllokut qe kufizohet nga rruga Endri Keko, Sadik Petrela dhe i trotuareve dhe rruges "Hoxha Tahsim" dhe Xhanfize Keko Rikonstruksioni i Infrastruktures rrugore te bllokut kufizuar nga rruga Njazi Meka - Grigor Perlecev-Niko Avrami -Spiro Cipi - Fitnetet Rexha - Myslym Keta -Skeneder Vila dhe lumi i Tiranes Rikonstruksion i rruges " Imer Ndregjoni " Rikonstruksioni i rruges "Dhimiter Shuteriqi" Rikonstruksioni i infrastruktures rrugore te bllokut kufizuar nga rruget Konferenca e Pezes - 3 Deshmoret dhe rruga Ali Jegeni Rikonstruksioni i rruges Zall - Bastarit (Ura Zall Dajt deri ne Zall Bastar) - Loti II. Rikonstruksioni i infrastruktures rrugore te bllokut qe kufizohet nga rruga Besa - Siri Kodra - Zenel Bastari - Haki Rexhep Kodra (perfshin dhe rrugen tek Nish Kimike) Rikonstruksioni i infrastruktures rrugore te bllokut qe kufizohet -

English and INTRODACTION

CHANGES AND CONTINUITY IN EVERYDAY LIFE IN ALBANIA, BULGARIA AND MACEDONIA 1945-2000 UNDERSTANDING A SHARED PAST LEARNING FOR THE FUTURE 1 This Teacher Resource Book has been published in the framework of the Stability Pact for South East Europe CONTENTS with financial support from the Dutch Ministry of Foreign Affairs. It is available in Albanian, Bulgarian, English and INTRODACTION..............................................3 Macedonian language. POLITICAL LIFE...........................................17 CONSTITUTION.....................................................20 Title: Changes and Continuity in everyday life in Albania, ELECTIONS...........................................................39 Bulgaria and Macedonia POLITICAL PERSONS..............................................50 HUMAN RIGHTS....................................................65 Author’s team: Terms.................................................................91 ALBANIA: Chronology........................................................92 Adrian Papajani, Fatmiroshe Xhemali (coordinators), Agron Nishku, Bedri Kola, Liljana Guga, Marie Brozi. Biographies........................................................96 BULGARIA: Bibliography.......................................................98 Rumyana Kusheva, Milena Platnikova (coordinators), Teaching approches..........................................101 Bistra Stoimenova, Tatyana Tzvetkova,Violeta Stoycheva. ECONOMIC LIFE........................................103 MACEDONIA: CHANGES IN PROPERTY.......................................104 -

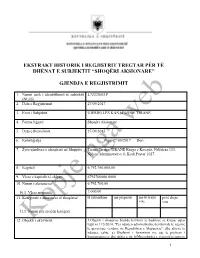

Datë 06.03.2021

EKSTRAKT HISTORIK I REGJISTRIT TREGTAR PËR TË DHËNAT E SUBJEKTIT “SHOQËRI AKSIONARE” GJENDJA E REGJISTRIMIT 1. Numri unik i identifikimit të subjektit L72320033P (NUIS) 2. Data e Regjistrimit 27/09/2017 3. Emri i Subjektit UJËSJELLËS KANALIZIME TIRANË 4. Forma ligjore Shoqëri Aksionare 5. Data e themelimit 27/09/2017 6. Kohëzgjatja Nga: 27/09/2017 Deri: 7. Zyra qëndrore e shoqërisë në Shqipëri Tirane Tirane TIRANE Rruga e Kavajës, Ndërtesa 133, Njësia Administrative 6, Kodi Postar 1027 8. Kapitali 6.792.760.000,00 9. Vlera e kapitalit të shlyer: 6792760000.0000 10. Numri i aksioneve: 6.792.760,00 10.1 Vlera nominale: 1.000,00 11. Kategoritë e aksioneve të shoqërisë të zakonshme me përparësi me të drejte pa të drejte vote vote 11.1 Numri për secilën kategori 12. Objekti i aktivitetit: 1.Objekti i shoqerise brenda territorit te bashkise se krijuar sipas ligjit nr.l 15/2014, "Per ndarjen administrative-territoriale te njesive te qeverisjes vendore ne Republiken e Shqiperise", dhe akteve te ndarjes, eshte: a) Sherbimi i furnizimit me uje te pijshem i konsumatoreve dhe shitja e tij; b)Mirembajtja e sistemit/sistemeve 1 te furnizimit me ujë te pijshem si dhe të impianteve te pastrimit te tyre; c)Prodhimi dhe/ose blerja e ujit per plotesimin e kerkeses se konsumatoreve; c)Shërbimi i grumbullimit, largimit dhe trajtimit te ujerave te ndotura; d)Mirembajtja e sistemeve te ujerave te ndotura, si dhe të impianteve të pastrimit të tyre. 2.Shoqeria duhet të realizojë çdo lloj operacioni financiar apo tregtar që lidhet direkt apo indirect me objektin e saj, brenda kufijve tè parashikuar nga legjislacioni në fuqi. -

Faded Memories

Faded Memories Life and Times of a Macedonian Villager 1 The COVER PAGE is a photograph of Lerin, the main township near the villages in which many of my family ancestors lived and regularly visited. 2 ACKNOWLEGEMENTS This publication is essentially an autobiography of the life and times of my father, John Christos Vellios, Jovan Risto Numeff. It records his recollections, the faded memories, passed down over the years, about his family ancestors and the times in which they lived. My father personally knew many of the people whom he introduces to his readers and was aware of more distant ancestors from listening to the stories passed on about them over the succeeding generations. His story therefore reinforces the integrity of oral history which has been used since ancient times, by various cultures, to recall the past in the absence of written, documentary evidence. This publication honours the memory of my father’s family ancestors and more generally acknowledges the resilience of the Macedonian people, who destined to live, seemingly forever under foreign subjugation, refused to deny their heritage in the face of intense political oppression and on-going cultural discrimination. This account of life and times of a Macedonian villager would not have been possible without the support and well-wishes of members of his family and friends whose own recollections have enriched my father’s narrative. I convey my deepest gratitude for the contributions my father’s brothers, my uncles Sam, Norm and Steve and to his nephew Phillip (dec), who so enthusiastically supported the publication of my father’s story and contributed on behalf of my father’s eldest brother Tom (dec) and his family. -

ANNUAL REPORT 2013 Message from Message Credins the General from the Bank’S Activity 01Director 02 Board 03During 2013 Table of Content

ANNUAL REPORT 2013 MESSAGE FROM MESSAGE CREDINS THE GENERAL FROM THE BANK’s ACTIVITY 01DIRECtor 02 Board 03DURING 2013 TABLE OF CONTENT MAIN ADDRESSES OF FINANCIAL tableS OBJECTIVES CREDINS BANK’s AND THE report FOR 2014 BRANCHES AND OF INDEPENDENT 05 06 audItorS 04 AGENCIES Artan SANTO General Director MESSAGE FROM THE GENERAL DIRECtor Dear readers, Credins Bank is in constant process of growth and transformation. This year we have marked 10 years of work, passion, desire and fatigue, to overcome yesterday, towards a different tomorrow from today. All the challenges that we encounter are the starting point for change and progress. 2013 was a difficult year. Regarding the Albanian economy, I would characterize it as the most difficult year, where structural changes left consequences in the economy. But it was overcome, with a great responsibility, desire and commitment to the common good. We are now ranked among the top banks of the Albanian banking market. We have maximized everything in our whole organization. We increased sales, analysis and control. We have reformed the structure according to a market that experienced weakness and oscillation, but also endurance. We have focused on existing customers supporting their business, but also on the new ones. We have learned from the appalling economic factors and focused on such sectors where need and demand for products provides lifespan, expanding lending and comprehensive support. Our financial results during 2013 are indicative of a sustainable and healthy development where is worth mentioning: In terms of performance of the entire banking system of the country, our deposit growth exceeded overall market growth with 3.42% and our growth in total loans exceeded the market which fell by 1.84%. -

Strategjia E Zhvillimit Të Qendrueshëm Bashkia Tiranë 2018

STRATEGJIA E ZHVILLIMIT TË QENDRUESHËM TË BASHKISË TIRANË 2018 - 2022 DREJTORIA E PËRGJITSHME E PLANIFIKIMIT STRATEGJIK DHE BURIMEVE NJERËZORE BASHKIA TIRANË Tabela e Përmbajtjes Përmbledhje Ekzekutive............................................................................................................................11 1. QËLLIMI DHE METODOLOGJIA...............................................................................................................12 1.1 QËLLIMI...........................................................................................................................................12 1.2 METODOLOGJIA..............................................................................................................................12 1.3 PARIMET UDHËHEQËSE..................................................................................................................14 2. TIRANA NË KONTEKSTIN KOMBËTAR DHE NDËRKOMBËTAR.................................................................15 2.1 BASHKËRENDIMI ME POLITIKAT DHE PLANET KOMBËTARE...........................................................15 2.2 KONKURUESHMËRIA DHE INDIKATORËT E SAJ...............................................................................13 2.2.1 Burimet njerëzore dhe cilësia e jetës......................................................................................13 2.2.2 Mundësitë tregtare dhe potenciali prodhues.........................................................................14 2.2.3 Transport...............................................................................................................................15 -

From Small-Scale Informal to Investor-Driven Urban Developments

Mitteilungen der Österreichischen Geographischen Gesellschaft, 162. Jg., S. 65–90 (Annals of the Austrian Geographical Society, Vol. 162, pp. 65–90) Wien (Vienna) 2020, https://doi.org/10.1553/moegg162s65 Busting the Scales: From Small-Scale Informal to Investor-Driven Urban Developments. The Case of Tirana / Albania Daniel Göler, Bamberg, and Dimitër Doka, Tirana [Tiranë]* Initial submission / erste Einreichung: 05/2020; revised submission / revidierte Fassung: 08/2020; final acceptance / endgültige Annahme: 11/2020 with 6 figures and 1 table in the text Contents Summary .......................................................................................................................... 65 Zusammenfassung ............................................................................................................ 66 1 Introduction ................................................................................................................ 67 2 Research questions and methodology ........................................................................ 71 3 Conceptual focus on Tirana: Moving towards an evolutionary approach .................. 72 4 Large urban developments in Tirana .......................................................................... 74 5 Discussion and problematisation ................................................................................ 84 6 Conclusion .................................................................................................................. 86 7 References ................................................................................................................. -

Economic and Social Council

UNITED E NATIONS Economic and Social Distr. Council GENERAL E/1990/5/Add.67 11 April 2005 Original: ENGLISH Substantive session of 2005 IMPLEMENTATION OF THE INTERNATIONAL COVENANT ON ECONOMIC, SOCIAL AND CULTURAL RIGHTS Initial reports submitted by States parties under articles 16 and 17 of the Covenant Addendum ALBANIA* [5 January 2005] * The information submitted by Albania in accordance with the guidelines concerning the initial part of reports of States parties is contained in the core document (HRI/CORE/1/Add.124). GE.05-41010 (E) 110505 E/1990/5/Add.67 page 2 CONTENTS Paragraphs Page Introduction .............................................................................................. 1 - 3 3 Article 1 .................................................................................................... 4 - 9 3 Article 2 .................................................................................................... 10 - 34 11 Article 3 .................................................................................................... 35 - 44 14 Article 6 .................................................................................................... 45 - 100 16 Article 7 .................................................................................................... 101 - 154 27 Article 8 .................................................................................................... 155 - 175 38 Article 9 .................................................................................................... 176 -

Albania: Average Precipitation for December

MA016_A1 Kelmend Margegaj Topojë Shkrel TRO PO JË S Shalë Bujan Bajram Curri Llugaj MA LËSI Lekbibaj Kastrat E MA DH E KU KË S Bytyç Fierzë Golaj Pult Koplik Qendër Fierzë Shosh S HK O D Ë R HAS Krumë Inland Gruemirë Water SHK OD RË S Iballë Body Postribë Blerim Temal Fajza PUK ËS Gjinaj Shllak Rrethina Terthorë Qelëz Malzi Fushë Arrëz Shkodër KUK ËSI T Gur i Zi Kukës Rrapë Kolsh Shkodër Qerret Qafë Mali ´ Ana e Vau i Dejës Shtiqen Zapod Pukë Malit Berdicë Surroj Shtiqen 20°E 21°E Created 16 Dec 2019 / UTC+01:00 A1 Map shows the average precipitation for December in Albania. Map Document MA016_Alb_Ave_Precip_Dec Settlements Borders Projection & WGS 1984 UTM Zone 34N B1 CAPITAL INTERNATIONAL Datum City COUNTIES Tiranë C1 MUNICIPALITIES Albania: Average Produced by MapAction ADMIN 3 mapaction.org Precipitation for D1 0 2 4 6 8 10 [email protected] Precipitation (mm) December kilometres Supported by Supported by the German Federal E1 Foreign Office. - Sheet A1 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 Data sources 7 8 9 0 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 0 1 2 - - - 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 2 2 2 The depiction and use of boundaries, names and - - - - - - - - - - - - - F1 .1 .1 .1 GADM, SRTM, OpenStreetMap, WorldClim 0 0 0 .1 .1 .1 .1 .1 .1 .1 .1 .1 .1 .1 .1 .1 associated data shown here do not imply 6 7 8 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 9 0 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 0 1 endorsement or acceptance by MapAction. -

3 Description of the Paskuqan Primary 9 Year School

ENVIRONMENTAL ASSESSMENT FOR Public Disclosure Authorized CONSTRUCTION OF NEW 9 YEAR PRIMARY SCHOOL IN PASKUQAN UNDER EDUCATION EXCELLENCE AND EQUITY PROJECT (EEE-P) Public Disclosure Authorized Public Disclosure Authorized Public Disclosure Authorized 1 Table of content 1 INTRODUCTION ........................................................................................................ 5 2 DESCRIPTION OF THE PROJECT ........................................................................ 5 2.1 Objectives of the Project ...................................................................................... 5 2.2 Project priorities................................................................................................... 5 2.3 Major physical investments ................................................................................. 6 3 DESCRIPTION OF THE PASKUQAN PRIMARY 9 YEAR SCHOOL ............... 8 3.1 The school and the site ......................................................................................... 8 3.2 School surroundings .......................................................................................... 11 4 ENVIRONMENTAL BASELINE CONDITIONS ................................................. 13 4.1 Physical environment ......................................................................................... 13 4.1.1 Geology .......................................................................................................... 13 4.1.2 Hydrogeology ................................................................................................ -

The Truth About Greek Occupied Macedonia

TheTruth about Greek Occupied Macedonia By Hristo Andonovski & Risto Stefov (Translated from Macedonian to English and edited by Risto Stefov) The Truth about Greek Occupied Macedonia Published by: Risto Stefov Publications [email protected] Toronto, Canada All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording or by any information storage and retrieval system without written consent from the author, except for the inclusion of brief and documented quotations in a review. Copyright 2017 by Hristo Andonovski & Risto Stefov e-book edition January 7, 2017 2 TABLE OF CONTENTS Preface................................................................................................6 CHAPTER ONE – Struggle for our own School and Church .......8 1. Macedonian texts written with Greek letters .................................9 2. Educators and renaissance men from Southern Macedonia.........15 3. Kukush – Flag bearer of the educational struggle........................21 4. The movement in Meglen Region................................................33 5. Cultural enlightenment movement in Western Macedonia..........38 6. Macedonian and Bulgarian interests collide ................................41 CHAPTER TWO - Armed National Resistance ..........................47 1. The Negush Uprising ...................................................................47 2. Temporary Macedonian government ...........................................49