The Unknown Variable: Multiple Target Markets in One…

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Feature Film Project Summary Logline Synopsis

HERE Feature Film Project Summary A Braden King Film Written by Braden King and Dani Valent Producers: Lars Knudsen, Jay Van Hoy Co-Producer: Jeff Kalousdian Executive Producers: Zoe Kevork, Julia King A Truckstop Media / Parts and Labor Production 302A W. 12th St., #223 New York, New York 10014 (212) 989-7105 / [email protected] www.herefilm.info Logline HERE is a dramatic, landscape-obsessed road movie that chronicles a brief but intense romantic relationship between an American satellite-mapping engineer and an expatriate Armenian art photographer who impulsively decide to travel together into uncharted territory. Synopsis Will Shepard is an American satellite-mapping engineer contracted to create a new, more accurate survey of the country of Armenia. Within the industry, his solitary work - land-surveying satellite images to check for accuracy and resolve anomalies - is called “ground-truthing”. He’s been doing it on his own, for years, all over the world. But on this trip, his measurements are not adding up. Will meets Gadarine Najarian at a rural hotel. Tough and intriguing, she’s an expatriate Armenian art photographer on her first trip back in ages, passionately trying to figure out what kind of relationship - if any - she still has with her home country and culture. Fiercely independent, Gadarine is struggling to resolve the life she’s led abroad with the Armenian roots that run so deeply through her. There is an instant, unconscious bond between these two lone travelers; they impulsively decide to continue together. HERE tells the story of their unique journey and the dramatic personal transformations it leads each of them through. -

A Lengthwise Slash David Grubbs, 2011 I First Met Arnold Dreyblatt In

A Lengthwise Slash David Grubbs, 2011 I first met Arnold Dreyblatt in 1996 when he came to Chicago at Jim O’Rourke’s urging. At the time Jim and I were the two core members of the group Gastr del Sol, and we also co-directed the Dexter’s Cigar reissue label for Drag City. The basic idea of Dexter’s Cigar was that there were any number of out-of-print, underappreciated recordings that, if heard, would put contemporary practitioners to shame. Just try to stack your solo free-improv guitar playing versus Derek Bailey’s Aida. Think your power electronics group is hot? Care to take a listen to Merzbow’s Rainbow Electronics 2? Do you fancy a shotgun marriage of critical theory and ramshackle d.i.y. pop? But you’ve never heard the Red Krayola and Art and Language’s Corrected Slogans? Gastr del Sol work time was as often as not spent sharing new discoveries and musical passions. Jim and I both flipped to Dreyblatt’s 1995 Animal Magnetism (Tzadik; which Jim nicely described “as if the Dirty Dozen Brass Band got a hold of some of Arnold’s records and decided to give it a go”) as well as his ingenious 1982 album Nodal Excitation (India Navigation), with its menagerie of adapted and homemade instruments (midget upright pianoforte, portable pipe organ, double bass strung with steel wire, and so on). We knew upon a first listen that we were obliged to reissue Nodal Excitation. The next time that Arnold blew through town, we had him headline a Dexter’s Cigar show at the rock club Lounge Ax. -

B E L G I E B E L G

Selectie uit muziekprogrammatie BB EE LL GG II EE - Hasselt periode 1 9 999 0 - 200666 1990 - Jeff Gielen (B) piano - Luc Van Acker (B) rock-akoestisch - Luc Van Lessen (B) experimenteel - Fake Fushion (B) experimenteel - Dark Rose (B) jazz-blues - Huns (B) experimenteel - Het Beranger Trio (B) zigeuner jazz - Morzelpronk (S) rock - Triptich (B) hardcore - 3 bessen en een bas (B) klassiek - Forty Busy Fingers (B) saxofoonkwartet - Red Flower (B) rock - Vincent Class Band (B) moderne jazz 1991 (°) = productie / project BELGIE - Guido Belcanto en het orkest zijner dromen (B) chanson - Collection d’Arnell Andrea (F) exp.filmmuziek ° DE AKOESTIEK IN BELGIE ‘91 - Derek and The Dirt (B) rock-akoestisch - The Candy Dates (B) rock-akoestisch - Dow Jones (B) rock-akoestisch - Les Prophètes (ZAÏRE) Afrikaanse soukous - Luc de Vos (B) solo ned-rock - Ted Milton (UK) exp.sax. poëzie/film - Ajnabi- groep (UK) Indië-dance - Salam (AFRIKA) soukous - Het Joustra Trio (B) klassiek - Nemo (B) pop-rock - Sex- Huns (B) rock 1992 (°) = productie / project BELGIE - Rudolf Hecke en Pop in Wonderland (B) rock-akoestisch - Marcel Vanhilt & co (B) satire - Berenger Trio (B) zigeuner muziek - Tom Wolf (B) pop-akoestisch - Jef Mercelis (B) akoestisch ° DE AKOESTIEK IN BELGIE ‘92 - The Pink Flowers (B) pop-akoestisch - Paul Landau & J.T. Moor (B) rock-akoestisch - Wigbert ‘Onder Dak’ (B) pop-akoestisch - The Sands (B) rock-akoestisch - Ajnabi Group (UK) indisch-bhangra - Bula Sangoma (ZAIRE) soukous - Dick Vanderharst & groep (NL) kamermuziek - The Beautiful Babies (B) rock - Luc Van Acker (B) folk-rock - The Danish Buttercookies pop-akoestisch - The Dizzy Dave band (B) blues - Black jack (B) solo-pop - The Lost Generation (B) pop-rock 1993 (°) = productie / project BELGIE - The Candy Men (B) rock-akoestisch - Les Merveilles du Passé (ZAÏRE) zaïrese soukous - Love is Colder Than Death (D) electro-wave - Mezcal (MX) salsa - Samy Birnbach and Benjamin Low (ISR) exp. -

2016-Program-Book-Corrected.Pdf

A flagship project of the New York Philharmonic, the NY PHIL BIENNIAL is a wide-ranging exploration of today’s music that brings together an international roster of composers, performers, and curatorial voices for concerts presented both on the Lincoln Center campus and with partners in venues throughout the city. The second NY PHIL BIENNIAL, taking place May 23–June 11, 2016, features diverse programs — ranging from solo works and a chamber opera to large scale symphonies — by more than 100 composers, more than half of whom are American; presents some of the country’s top music schools and youth choruses; and expands to more New York City neighborhoods. A range of events and activities has been created to engender an ongoing dialogue among artists, composers, and audience members. Partners in the 2016 NY PHIL BIENNIAL include National Sawdust; 92nd Street Y; Aspen Music Festival and School; Interlochen Center for the Arts; League of Composers/ISCM; Lincoln Center for the Performing Arts; LUCERNE FESTIVAL; MetLiveArts; New York City Electroacoustic Music Festival; Whitney Museum of American Art; WQXR’s Q2 Music; and Yale School of Music. Major support for the NY PHIL BIENNIAL is provided by The Andrew W. Mellon Foundation, The Fan Fox and Leslie R. Samuels Foundation, and The Francis Goelet Fund. Additional funding is provided by the Howard Gilman Foundation and Honey M. Kurtz. NEW YORK CITY ELECTROACOUSTIC MUSIC FESTIVAL __ JUNE 5-7, 2016 JUNE 13-19, 2016 __ www.nycemf.org CONTENTS ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS 4 DIRECTOR’S WELCOME 5 LOCATIONS 5 FESTIVAL SCHEDULE 7 COMMITTEE & STAFF 10 PROGRAMS AND NOTES 11 INSTALLATIONS 88 PRESENTATIONS 90 COMPOSERS 92 PERFORMERS 141 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS THE NEW YORK PHILHARMONIC ORCHESTRA THE AMPHION FOUNDATION DIRECTOR’S LOCATIONS WELCOME NATIONAL SAWDUST 80 North Sixth Street Brooklyn, NY 11249 Welcome to NYCEMF 2016! Corner of Sixth Street and Wythe Avenue. -

Sustaining Afrocentric Spiritual Jazz in 21St Century Chicago

City University of New York (CUNY) CUNY Academic Works All Dissertations, Theses, and Capstone Projects Dissertations, Theses, and Capstone Projects 9-2016 Sacred Freedom: Sustaining Afrocentric Spiritual Jazz in 21St Century Chicago Adam Zanolini The Graduate Center, City University of New York How does access to this work benefit ou?y Let us know! More information about this work at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu/gc_etds/1617 Discover additional works at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu This work is made publicly available by the City University of New York (CUNY). Contact: [email protected] SACRED FREEDOM: SUSTAINING AFROCENTRIC SPIRITUAL JAZZ IN 21ST CENTURY CHICAGO by ADAM ZANOLINI A dissertation submitted to the Graduate Faculty in Music in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy, The City University of New York 2016 © 2016 ADAM ZANOLINI All Rights Reserved ii Sacred Freedom: Sustaining Afrocentric Spiritual Jazz in 21st Century Chicago by Adam Zanolini This manuscript has been read and accepted for the Graduate Faculty in Music in satisfaction of the dissertation requirement for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy. _________________ __________________________________________ DATE David Grubbs Chair of Examining Committee _________________ __________________________________________ DATE Norman Carey Executive Officer Supervisory Committee: _________________ __________________________________________ DATE Jeffrey Taylor _________________ __________________________________________ DATE Fred Moten _________________ __________________________________________ DATE Michele Wallace iii ABSTRACT Sacred Freedom: Sustaining Afrocentric Spiritual Jazz in 21st Century Chicago by Adam Zanolini Advisor: Jeffrey Taylor This dissertation explores the historical and ideological headwaters of a certain form of Great Black Music that I call Afrocentric spiritual jazz in Chicago. However, that label is quickly expended as the work begins by examining the resistance of these Black musicians to any label. -

Mick Geyer in 1996: NC: Mr Mick Geyer, My Chief Researcher and Guru, He Is the Man Behind the Scenes

www.pbsfm.org.au FULL TRANSCRIPT OF DOCUMENTARY #3 First broadcast on PBS-FM Wednesday 12 April 2006, 7-8pm Nick Cave interviewing Mick Geyer in 1996: NC: Mr Mick Geyer, my chief researcher and guru, he is the man behind the scenes. How important is music to you? MG: It seems to be a fundamental spirit of existence in some kind of way. The messages of musicians seem to be as relevant as those of any other form of artistic expression. MUSIC: John Coltrane - Welcome (Kulu Se Mama) LISA PALERMO (presenter): Welcome to 'Mick Geyer: Music Guru'. I'm Lisa Palermo and this is the third of four documentaries paying tribute to Mick, a broadcaster and journalist in the Melbourne music scene in the 1980's and '90's. Mick died in April 2004 of cancer of the spine. He had just turned 51. His interests and activities were centred on his love of music, and as you'll hear from recent interviews and archival material, his influence was widespread, but remained largely outside the public view. In previous programs we heard about the beginnings of his passion for music, and his role at PBS FM, behind the scenes and on the radio. Now we'll explore Mick as a catalyst and friend to many musicians, through conversation and the legendary Geyer tapes, those finely crafted compilations of musical enlightenment and education. In this program we'll hear for the first time from: musicians Dave Graney & Clare Moore, Jex Saarelaht, Hugo Race, Tex Perkins, Warren Ellis, Kim Salmon, Brian Hooper, Charlie Owen, and Penny Ikinger; and from friends Beau Cummin, Mariella del Conte, Stephen Walker and Warwick Brown. -

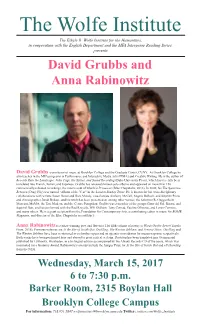

The Wolfe Institute the Ethyle R

The Wolfe Institute The Ethyle R. Wolfe Institute for the Humanities, in cooperation with the English Department and the MFA Intergenre Reading Series, presents David Grubbs and Anna Rabinowitz David Grubbs is professor of music at Brooklyn College and the Graduate Center, CUNY. At Brooklyn College he also teaches in the MFA programs in Performance and Interactive Media Arts (PIMA) and Creative Writing. He is the author of Records Ruin the Landscape: John Cage, the Sixties, and Sound Recording (Duke University Press), which has recently been translated into French, Italian, and Japanese. Grubbs has released thirteen solo albums and appeared on more than 150 commercially-released recordings, the most recent of which is Prismrose (Blue Chopsticks, 2016). In 2000, his The Spectrum Between (Drag City) was named “Album of the Year” in the London Sunday Times. He is known for his cross-disciplinary collaborations with writers Susan Howe and Rick Moody, visual artists Anthony McCall, Angela Bulloch, and Stephen Prina, and choreographer Jonah Bokaer, and his work has been presented at, among other venues, the Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum, MoMA, the Tate Modern, and the Centre Pompidou. Grubbs was a member of the groups Gastr del Sol, Bastro, and Squirrel Bait, and has performed with the Red Krayola, Will Oldham, Tony Conrad, Pauline Oliveros, and Loren Connors, and many others. He is a grant recipient from the Foundation for Contemporary Arts, a contributing editor in music for BOMB Magazine, and director of the Blue Chopsticks record label. Anna Rabinowitz is a prize-winning poet and librettist. Her fifth volume of poetry isWords On the Street (Tupelo Press, 2016). -

Geföhnter Hardcore

# 2008/43 dschungel https://jungle.world/artikel/2008/43/gefoehnter-hardcore Die neue Platte von David Grubbs Geföhnter Hardcore Von Martin Büsser Squirrel Bait, diese Vereinigung 16jähriger Teenager, die Stücke über Vergil machten, kamen in den Achtzigern zu früh. Jetzt kann man sich die Pionierarbeit von Postrock retrospektiv anhören und auch, wie David Grubbs heute klingt. Für einige Menschen war die erste Hälfte der achtziger Jahre ein musikalisches Paradies. So zumindest sieht es Paul Rachman, Regisseur des viel beachteten Dokumentarfilms »American Hardcore« (2006). Von MTV und dessen Hörern völlig ignoriert, entstand zu dieser Zeit in den USA eine vitale Szene, die völlig auf sich selbst gestellt war, eigene Labels und Netzwerke hervorbrachte und innerhalb kürzester Zeit zu Hunderten von Bandgründungen führte. Doch selbst ein Fan wie Rachman kann nicht ignorieren, dass die Szene fast ausschließlich von Männern dominiert wurde, weißen Männern. Und ausgerechnet die einzige schwarze Hardcore-Band, The Bad Brains, war für ihre Schwulenfeindlichkeit berüchtigt. Von solchen gender politics einmal abgesehen, hatte die Szene allerdings noch einen ganz anderen gravierenden Schönheitsfehler: Nahezu alle Bands hörten sich gleich an. Hardcore war Ausdruck ungefilterter jugendlicher Wut, musikalische Feinheiten wurden da nicht so genau genommen. Unter rein musikalischen Gesichtspunkten ist »American Hardcore« daher auch ein sterbenslangweiliger Film, aus dessen Einheitsgeknüppel gerade einmal Black Flag, die notorisch unterschätzten Flipper und Minutemen hervorstechen. Letztgenannte seien »zu erwachsen für die Hardcore- Szene« gewesen, hatte Thurston Moore von Sonic Youth einmal gesagt. Das könnte man auch von Squirrel Bait behaupten. Liest sich aber komisch, wenn man bedenkt, dass die Musiker zur Zeit der Bandgründung gerade einmal 16 Jahre alt waren. -

Notes on Deconstructing Popular Music (Studies): Global Media and Critical Interventions

NOTES ON DECONSTRUCTING POPULAR MUSIC (STUDIES): GLOBAL MEDIA AND CRITICAL INTERVENTIONS February 19-21, 2015 University of Louisville iaspm-us.net IASPM-US 2015 CONFERENCE HOSTED BY The University of Louisville Commonwealth Center for Humanities and Society Aaron Jaffe, Director College of Arts & Sciences Kimberly Kempf-Leonard, Dean Liberal Studies Project John Hale, Director Women’s and Gender Studies Department Nancy Theriot, Chair Department of English Glynis Ridley, Chair University Libraries Bob Fox, Dean Bruce Keisling, Associate Dean Latin American and Latino Studies Program Rhonda Buchanan, Director LGBT Center Brian Buford, Director Endowed Chair in Rhetoric and Composition Bruce Horner, Professor of English Louisville Underground Music Archive Carrie Daniels, Director The Muhammad Ali Center Donald E. Lassere, President Marcel Parent, Senior Director of Education, Outreach, and Curation 2 WITH SPECIAL THANKS TO OUR COMMUNITY PARTNERS ARTxFM Radio Decca Guestroom Records Kentucky Museum of Art and Craft The New Vintage The Other Side of Life 3 IASPM- US PRESIDENT’S ADDRESS On behalf of the United States Branch of the International Association for the Study of Popular Music, I welcome you to our 2014 conference, “Notes On Deconstructing Popular Music (Studies): Global Media And Critical Interventions.” This year’s conference is hosted by a consortium of departments and programs at the University of Louisville, in conjunction with the Muhammad Ali Center. In the tradi- tion of the Louisville native who has spent a lifetime living up to his honorific, “the Greatest,” we will gather to reaffirm our collective creed: that popular music studies, though it may seem to float like a butterfly, can, when done right, sting like a bee. -

The Lost Generation How UK Post-Rock Fell in Love with the Moon, and a Bunch of Bands Nobody Listened to Defined the 1990S by Nitsuh Abebe

Pitchfork | http://pitchforkmedia.com/features/weekly/05-07-11-lost-generation.shtml 11 July 2005 The Lost Generation How UK post-rock fell in love with the moon, and a bunch of bands nobody listened to defined the 1990s by Nitsuh Abebe his decade’s indie-kid rhetoric is all about excitement, all about fun, all about fierce. TThe season’s buzz tour pairs ... with Soundsystem, scrappy globo-pop with the kind of rock disco that tries awfully hard to blow fuses. The venues they don’t hit will play host to a new wave of stylish guitar bands, playing stylish uptempo pop, decamping to stylish afterparties. Bloggers will chatter about glittery chart hits, rock kids will buy vintage metal t-shirts and act like heshers, eggheads will rave about the latest in spazzed-out noise, and everyone will keep talking about dancing, right down to the punks. Yeah, there are more exceptions than there are examples—when aren’t there, dude?—but the vibe is all there: We keep talking like we want action, like we want something explosive. The overriding vibe of the s—serene, cerebral, dreamy—was anything but explosive. Blame grunge for that one. Just a few years into the decade, and all that muddy rock attitude and fuzzy alterna-sound had bubbled up into the mainstream, flooding the scene with new kids, young kids, even (gasp!) fratboys. Big kids in flannel, freshly enamored of rock’s “aggres- sion” and “rebellion”—they were rock jocks, they tried to start mosh pits at Liz Phair shows. So where was a refined little smarty-pants indie snob to turn? Well: Why not something spacey and elegant? Why not sit comfortably home, stoned or non-stoned, dropping out into a dreamier little world of sound? It had been a few years since My Bloody Valentine released Loveless, and there were plenty of similarly floaty shoegazer bands to catch up on. -

The Evening Hour

presents THE EVENING HOUR A FILM BY BRADEN KING Written by Elizabeth Palmore Based on the Novel by Carter Sickels Starring Philip Ettinger, Stacy Martin, Lili Taylor PRESS NOTES OFFICIAL SELECTION Sundance Film Festival International Film Festival Rotterdam Country of Origin: USA Format: DCP/2.39/Color Sound: 5.1 Surround Running Time: 114 minutes Genre: Drama Not Rated In English NY / National Press Contact: LA/National Press Contact: Betsy Rudnick Fernand Carly Hildebrant [email protected] [email protected] Strand Releasing 310 836 7500 SYNOPSIS Cole Freeman maintains an uneasy equilibrium in his Appalachian town, looking after the old and infirm in the community while selling their excess painkillers to local addicts to make ends meet. But when an old friend returns with dangerous new plans that threaten the fragile balance Cole has crafted in his declining mountain town, his world and identity are thrown into deep disarray. THE EVENING HOUR is an authentic portrait of a rural American landscape in transition - a moving, lyrical hymn for the complex tangle of hardship and hope wrought by the opioid addiction in Appalachia. TO SEE AND BE SEEN “The Evening Hour began as a book by Carter Sickels, born of Carter’s talking to people in the southern mountains about what was happening in their lives. His novel grew out of a documentary impulse and was received by the region as a beautiful new friend, immediately recognized and accepted. When Braden King and his friends came to my part of the southern mountains to shoot a film based on Carter’s book, they took similar care to acknowledge and discover where they were. -

UIS - Unrock Import Service 2005

UIS - Unrock Import Service 2005 Juli / August (203) LP (551) |___ 0-9 (4) |___ A-D (145) |___ E-H (94) |___ I-L (60) |___ M-P (112) |___ Q-T (94) |___ U-Z (42) CD (673) |___ 0-9 (4) |___ A-D (192) |___ E-H (112) |___ I-L (76) |___ M-P (113) |___ Q-T (114) |___ U-Z (62) 7"/10"/12" (226) |___ 0-9 (7) |___ A-D (59) |___ E-H (36) |___ I-L (23) |___ M-P (40) |___ Q-T (42) |___ U-Z (19) SALE (221) |___ 7"/10"/12" (77) |___ CD-Singles (16) |___ CD´s (99) |___ LP´s (29) Crypt Records (77) DVD (21) SUBLIME FREQUENCIES (15) Page 1/322 UIS - Unrock Import Service 2005 : Juli / August 7 Year Rabbit - Wind Machines LP Free Porcupine Society ***Free Porcupine Society schätzt sich glücklich diese absolute De-Luxe Edition von 7 Year Rabbit´s - Wind Machines zugänglich zu machen. Angeführt vom früheren Deerhoof Gitarristen Rob Fisk und seiner Streiterin Kelly Goodefisk (ebenfalls von Deerhoo) mit Miya Osaki und Steve Gigante von Brother Jt und Gaststar Jamie Stewart von Xiu Xiu, liefern 7 Year Rabbit 10 Tracks brutalster Improvisation und glühenden Vocals, geeignet jede Komposition zu skelettieren. 140 g. Vinyl gepackt in wunderschöne, handbdruckte Jackets mit Artwork von Herrn Fisk. Limitierte Ausgabe von allerhöchstens 500 Kopien. 18.90€ Acid King - III Small Stone ***Mit "III" kommen ACID KING der Idealvorstellung dessen, was man gemeinhin unter "Stoner Rock" versteht, gefährlich nahe. Gemeinsam mit Produzenten Legende Billy Anderson (MELVINS, MR.