The ASEAN Journey: Reflections of ASEAN Leaders and Officials

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Speech by the Secretary-General of ASEAN, Dr Surin Pitsuwan 2008 ASEAN Business and Investment Summit Bangkok, 26 February 2009

Speech by the Secretary-General of ASEAN, Dr Surin Pitsuwan 2008 ASEAN Business and Investment Summit Bangkok, 26 February 2009 H.E. Governor of Bangkok Mr Arin Jira, Chairman of the ASEAN-Business Advisory Council Members of ABAC Distinguished Guests, Ladies and Gentlemen, I am here today to talk about business in the marketplace of ASEAN. As you know, the ten economies of ASEAN are being integrated into an ASEAN Economic Community (AEC) and implemented through the AEC Blueprint. This AEC Blueprint is the only one among the three that has been approved and is being implemented over the past year. I understand that you already have a preview of the AEC Blueprint yesterday. The AEC Blueprint is the roadmap of ASEAN integration. ASEAN would like to see the ten economies combine and become one market. ASEAN would like to be one market and an equitable landscape with not too much diversity and gaps. ASEAN would like to see all ten economies be competitive with the rest of the world and as one single production base integrated into the global economy. These are the goals. We have the strategies and projects to drive the ten markets into one single entity with 575 million consumers and the growing and rising middle-class, which is not much less than the middle-class of China and not less than the middle class of India. The purchasing power of the region is attractive for business, investors and MNCs. At the heart of our strategies is to reduce tariffs; eliminate non-tariff measures; reduce the gaps in order to increase purchasing power across ASEAN; attract investors; and, institute rules and regulations to protect investment and intellectual property. -

East Asia Forum Quarterly: Volume 2, Number 2, 2010

EASTEc ONOmIcS, POlItIcS AND PuBASIAlIc POlIcy IN EASt ASIA ANDFORUM thE PAcIFIc Vol.2 No.2 April-June 2010 $9.50 Quarterly Questions for Southeast Asia Surin Pitsuwan ASEAN central to the region’s future Andrew MacIntyre Obama in Indonesia and Australia Dewi Fortuna Anwar Indonesia, the region and the world Thitinan Pongsudhirak Thailand’s unstoppable red shirts Tim Soutphommasane From stir-fries to ham sandwiches Ingrid Jordt Burma’s protests and their aftermath Greg Fealy Jemaah Islamiyah, Dulmatin and the Aceh cell and more . EASTASIAFORUM CONTENTS Quarterly 4 surin pitsuwan ISSN 1837-5081 (print) ASEAN central to the region’s future ISSN 1837-509X (online) From the Editor’s desk 6 andrew macintyre common causes: Obama in Indonesia and Southeast Asia defies simple categorisation. Among its countries Australia there are obvious contrasts: big and small, vibrant and stagnant, 8 don emmerson attractive and troubling, peaceful and unsettled, quaint and web- ASEAN and American engagement in East savvy, confronting and embracing. The contributors to this issue Asia of the EAFQ grapple with parts of the Southeast Asian mosaic, 10 dewi fortuna anwar punctuated, as ever, by domestic intrigues, national ambitions, and Indonesia, the region and the world international engagements. 11 greg fealy What ties the articles in this issue together, but never in a neat or terrorism today: Jemaah Islamiyah, seamless way, is the position of these countries, hemmed in by the Dulmatin and the Aceh cell much larger societies of china and India, and now forced to confront 13 thitinan pongsudhirak a world where ferocious technological and cultural change tests even The unstoppable red shirts the most effective governments. -

President Richard Nixon's Daily Diary, July 16-31, 1969

RICHARD NIXON PRESIDENTIAL LIBRARY DOCUMENT WITHDRAWAL RECORD DOCUMENT DOCUMENT SUBJECT/TITLE OR CORRESPONDENTS DATE RESTRICTION NUMBER TYPE 1 Manifest Helicopter Passenger Manifest 7/30/1969 A 2 Manifest Helicopter Passenger Manifest from Don- 7/30/1969 A Maung Airport, Bangkok 3 Manifest Helicopter Passenger Manifest – 7/23/1969 A Appendix “B” 4 Manifest Helicopter Passenger Manifest – 7/24/1969 A Appendix “A” 5 Manifest Helicopter Passenger Manifest – 7/26/1969 A Appendix “B” 6 Manifest Helicopter Passenger Manifest – 7/27/1969 A Appendix “A” COLLECTION TITLE BOX NUMBER WHCF: SMOF: Office of Presidential Papers and Archives RC-3 FOLDER TITLE President Richard Nixon’s Daily Diary July 16, 1969 – July 31, 1969 PRMPA RESTRICTION CODES: A. Release would violate a Federal statute or Agency Policy. E. Release would disclose trade secrets or confidential commercial or B. National security classified information. financial information. C. Pending or approved claim that release would violate an individual’s F. Release would disclose investigatory information compiled for law rights. enforcement purposes. D. Release would constitute a clearly unwarranted invasion of privacy G. Withdrawn and return private and personal material. or a libel of a living person. H. Withdrawn and returned non-historical material. DEED OF GIFT RESTRICTION CODES: D-DOG Personal privacy under deed of gift -------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- NATIONAL ARCHIVES AND RECORDS ADMINISTRATION *U.S. GPO; 1989-235-084/00024 NA 14021 (4-85) rnc.~IIJc.I'" rtIl."I'\ttU 1"'AUI'4'~ UAILJ UIAtU (See Travel Record for Travel Activity) ---- -~-------------------~--------------I PLACi-· DAY BEGA;'{ DATE (Mo., Day, Yr.) JULY 16, 1969 TIME DAY THE WHITE HOUSE - Washington, D. -

Agnew Assails U.S. Critics of Ewitary Aid to Thailand Va,T

Agnew Assails U.S. Critics Of e WitaryvA,t Aid to Thailand By Jack Foisie Loa Amities TIrries BANGKOK, Jan. 4—The Thal government, which has always decried American criti- cism of some aspects of Thai- American military coopera- tion, gained a new supporter today in Vice President Spiro Agnew. Meeting with Prime Minis- ter Thanom Kittikachorn for two hours today, Agnew de- clared: "Some people back home are so anxious to make friends of our enemies that they even seem ready to make enemies of our friends," The quote was approved for attribution to the Vice Presi- dent by American officials who sat in on the closed ses- sion- It was the second time on his Asian trip, now in its sec- ond week, that Agnew had re- newed his criticism of televi- sion and newspaper reporting, and of the people who do not wholly support American in- volvement in the Vietnam war. His comment could also apply to Sens. J. W. Fulbright (D-Ark.), Stuart Symington ID-Mo.) and Albert Gore (D- Tenn.), who have questioned the extent of US. commit- ments to Thailand. 0 t h e r Senators have opposed use of U.S. troops alland or Laos mout congressional approval. Both American and Thai ac- counts of the Thanom-Agnew talks said that most doubts had been dispelled about the Associated Prens "Nixon doctrine" of gradual The Agnews tour grounds of the Bangkok Grand Palace de-escalation of American po- litical and military presence• American policy, and no less- in Asia. They said Agnew declared the ening of U.S. -

THE POLITICS of INCOME DISTRIBUTION in THAILAND by Brewster Grace August 1977

SOUTHEAST ASIA SERIES Vol. XXV No. 7 (Thailand) THE POLITICS OF INCOME DISTRIBUTION IN THAILAND by Brewster Grace August 1977 Introduction Diverse economic, cultural, and political forces the country. We can then describe how it is dis- have coalesced and clashed in Thailand since Field tributed, how the need for redistribution further Marshall Thanom Kittikachorn and General Pra- broadened demands for more economic and polit- pass Charusathien established their absolute dic- ical participation and opportunity, and how, as tatorship in 1971. Their rule by decree virtually these demands resulted in increased instability, eliminated popular political participation at a time reaction to them also increased. when corruption and economic decline began to severely restrict economic participation and oppor- Basic Wealth tunity by low and middle income groups-the majority of the population of Thailand. Thailand's 1976 Gross Domestic Product (GDP), at current prices was an estimated US16 billion. Conflict first appeared in 1973 when students Agriculture, the largest single contributor and em- organized and rebelled against the rule by decree of ployer, accounted for nearly 27 percent or $4.3 Thanom and Prapass. It grew rapidly during the billion. following three years of civilian, representative government when activist efforts to reform basic Historically, rice made up the principal part of distribution patterns within the economy led to this production. And still today land on which it is increasing confrontation with politicized estab- grown, the product itself, its trade and its milling- lished economic interests. The latter included all provide production opportunities for most much of the military and newly mobilized rural Thais. -

General Assembly

United Nations 74th GENERAL PLENARY MEETING ASSEMBLY Friday, 10 December 1993 FORTY-EIGHTH SESSION at 10 a.m. Official Records NEW YORK President: Mr. INSANALLY legislation and to develop systems of government in which (Guyana) the human rights of individuals and groups are enshrined and __________ protected. The meeting was called to order at 10.45 a.m. While the Universal Declaration remains a historic landmark in international relations, however, the concern of AGENDA ITEM 20 (continued) the United Nations for human rights must go beyond this one document. I draw members’ attention to the Charter of FORTY-FIFTH ANNIVERSARY OF THE UNIVERSAL the United Nations, which proclaims in its Article 1 that the DECLARATION OF HUMAN RIGHTS protection and promotion of human rights for all is, along with the maintenance of international peace and security and (a) REPORT OF THE SECRETARY-GENERAL the promotion of economic and social development, one of (A/48/506) the principal purposes of this Organization. (b) DRAFT DECISION (A/48/L.49) Experience over the years has taught us all that these three goals are themselves interrelated and mutually The PRESIDENT: I declare open the commemorative reinforcing. Genuine economic and social development meeting devoted to the observance of the forty-fifth cannot be possible without respect for human rights, nor can anniversary of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights. worldwide peace and security be achieved in a climate where human rights are not protected and respected. The I shall now make a statement in my capacity as right to development and the right to peace are two President of the General Assembly. -

Menanti Revisi

Penerbitan KBRI Kuala Lumpur http://www.facebook.com/eCaraka EDISI 25/11 GRATIS (TIDAK DIJUAL) www.kbrikualalumpur.org KDN: PP17256/03/2012(029244) MAY, 2011 PERESMIAN EMPAT DIVA DAKWAH HARUS KANTOR INDONESIA DITANDAI PELAYANAN DIRANCANG AKSI NYATA INFORMASI TKI DI TAMPIL DI LCCT MALAYSIA >06 >09 >15 MENANTI REVISI MOU PENATA LAKSANA RUMAH TANGGA MORATORIUM (pembekuan) penempatan melindungi hak-hak PLRT, termasuk atas hak- Penata Laksana Rumah Tangga (PLRT) atau hak asasi manusia. kerap disebut Pembantu Rumah Tangga Kedua negara menyadari bahwa bila (PRT) sejak tahun 2009 ke Malaysia, ditelaah dan dipahami lebih rinci, ketentuan- menimbulkan permasalahan yang merugikan ketentuan MoU 2006 banyak memuat bagi Pemerintah Indonesia dan Malaysia. kewajiban para PLRT dan sedikit sekali Di satu sisi, pembekuan ini mengakibatkan memuat hak-haknya. PLRT juga dibebani banyaknya warga negara Indonesia (WNI) biaya administratif dan dokumen hingga biaya yang kehilangan kesempatan untuk bekerja perjalanan yang pada gilirannya gaji mereka dan di sisi lain banyak warga Malaysia, dipotong oleh pengguna selama 6 (enam) khususnya ibu rumah tangga, yang tidak bulan. Penderitaan semakin lengkap ketika dapat melakukan aktivitas di luar rumah atau mereka dieksploitasi, yaitu dipekerjakan tidak dapat bekerja karena mereka harus tanpa istirahat dan hari libur, diperkerjakan menjaga anak dan mengurus rumah tangga. juga di kedai-kedai atau rumah-rumah lain, Kebijakan lisan yang diterapkan oleh menjaga orang tua atau orang sakit yang pemerintah Indonesia sejak tahun 2009 ini sebetulnya tugas seorang juru rawat. Yang merupakan reaksi keras dari pemerintah paling tidak manusiawi adalah sudah lelah dan bangsa Indonesia akibat banyaknya bekerja kemudian tidak digaji, dianiaya, kejadian-kejadian tragis yang menimpa atau dilarang beribadah dan dipaksa makan PLRT, dari masalah tidak dibayarnya gaji makanan yang bertentangan dengan sampai penganiayaan ringan, pemerkosaan, agamanya. -

The King's Nation: a Study of the Emergence and Development of Nation and Nationalism in Thailand

THE KING’S NATION: A STUDY OF THE EMERGENCE AND DEVELOPMENT OF NATION AND NATIONALISM IN THAILAND Andreas Sturm Presented for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy of the University of London (London School of Economics and Political Science) 2006 UMI Number: U215429 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. Dissertation Publishing UMI U215429 Published by ProQuest LLC 2014. Copyright in the Dissertation held by the Author. Microform Edition © ProQuest LLC. All rights reserved. This work is protected against unauthorized copying under Title 17, United States Code. ProQuest LLC 789 East Eisenhower Parkway P.O. Box 1346 Ann Arbor, Ml 48106-1346 I Declaration I hereby declare that the thesis, submitted in partial fulfillment o f the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy and entitled ‘The King’s Nation: A Study of the Emergence and Development of Nation and Nationalism in Thailand’, represents my own work and has not been previously submitted to this or any other institution for any degree, diploma or other qualification. Andreas Sturm 2 VV Abstract This thesis presents an overview over the history of the concepts ofnation and nationalism in Thailand. Based on the ethno-symbolist approach to the study of nationalism, this thesis proposes to see the Thai nation as a result of a long process, reflecting the three-phases-model (ethnie , pre-modem and modem nation) for the potential development of a nation as outlined by Anthony Smith. -

Download Article (PDF)

Advances in Engineering Research, volume 167 International Conference on Maritime and Archipelago (ICoMA 2018) The Exigency Of Comprehensive Maritime Policy To Materialize And Implement Indonesia’s Global Maritime Fulcrum Objective Nirmala Masilamani Business Law Department, BINUS University, Jakarta, Indonesia Southeast Asia maritime. Under the ruling of Abstract–For the past three years, since HayamWuruk and his Prime Minister, Gajah Mada, President Jokowi took up the office, Indonesia has been Indonesia experienced a Golden Age, and extended emphasizing its ambitious goal to transform the nation into a through much of the southern Malay Peninsula, Borneo, Sumatra and Bali. global maritime fulcrum and have been developing some According to the Negarakertagama (Desawarñana) projects and initiatives to achieve it. To transform Indonesia written in 1365, Majapahit was an empire of 98 tributaries, into the world maritime fulcrum was set to become the stretching from Sumatra to New Guinea [1]; consisting of present-day Indonesia, Singapore, Malaysia, Brunei, objective of the government. This paper discusses Indonesian Southern Thailand, Sulu Archipelago, Philippines, and East policy regarding maritime, including the country’s stance, Timor. Both Srivijaya and Majapahit were powerful naval kingdoms and renowned for their trading. strategy, and proposed actions resulted from the statutory Majapahit launched naval and military expedition. The regulations. It also analyzes whether the policy passed suffices expansion of Majapahit Empire also involved diplomacy the requirements to become the maritime fulcrum or not. The and alliances. Moreover, Majapahit had a strong fleet to conquer other territories and send out punitive expeditions. study uses a descriptive approach by reviewing and analyzing Therefore, Majapahit considered as a commercial trading some of relevant statutory regulations relating to maritime empire in a civilization of Asia and the greatest kingdom in Southeast Asia history. -

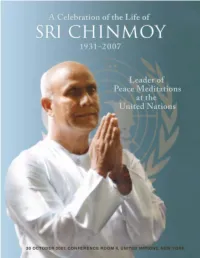

Pdf of Commemorative Booklet

Contents Introduction 2 Sri Chinmoy’s meetings and correspondence with the Secretaries-General of the United Nations 3 Selected tributes 8 Excerpts from Sri Chinmoy’s writings 18 1 Introduction In the spring of 1970, at the invitation of then of medical and health-care professionals, private Secretary-General U Thant, Sri Chinmoy began volunteers and concerned individuals from conducting twice-weekly non-denominational five continents who dedicate their lives to providing meditations for peace for United Nations staff food, clothing, medical supplies and other essentials members, delegates, NGO representatives and to those in need, including victims of poverty and affiliates. Since then, Sri Chinmoy: The Peace natural disasters. Meditation at the United Nations, as the group For 43 years Sri Chinmoy dedicated his life to the is known, has continued its meditations and has service of world peace and to the fulfilment of sponsored an ongoing series of programmes, the unlimited potential of the human spirit. Also a lectures and concerts to promote world harmony. prolific poet, essayist, artist and musician, and an These have often been in cooperation with avid athlete, he inspired citizens worldwide through UN Member States as well as with organizations his creative endeavours, through innovative peace which support the ideals and goals of the initiatives and through the example of his own United Nations. life. For 37 years he brought his multifaceted Sri Chinmoy also led a DPI-affiliated non- inspiration to the United Nations family in the governmental organization, the Sri Chinmoy spirit of selfless offering, encouraging individuals Centre, (www.srichinmoy.org) which conducts of all faiths, races and nationalities to seek a myriad of activities and strives to promote peace in their lives and to bring this peace to harmony and humanitarian aid across the globe. -

East Asia Summit Documents Series, 2005-2014

East Asia Summit Documents Series 2005 Summit Documents Series Asia - 2014 East East Asia Summit Documents Series 2005-2014 www.asean.org ASEAN one vision @ASEAN one identity one community East Asia Summit (EAS) Documents Series 2005-2014 ASEAN Secretariat Jakarta The Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN) was established on 8 August 1967. The Member States of the Association are Brunei Darussalam, Cambodia, Indonesia, Lao PDR, Malaysia, Myanmar, Philippines, Singapore, Thailand and Viet Nam. The ASEAN Secretariat is based in Jakarta, Indonesia. For inquiries, contact: The ASEAN Secretariat Public Outreach and Civil Society Division 70A Jalan Sisingamangaraja Jakarta 12110 Indonesia Phone : (62 21) 724-3372, 726-2991 Fax : (62 21) 739-8234, 724-3504 E-mail : [email protected] Catalogue-in-Publication Data East Asia Summit (EAS) Documents Series 2005-2014 Jakarta: ASEAN Secretariat, May 2015 327.59 1. A SEAN – East Asia 2. Declaration – Statement ISBN 978-602-0980-18-8 General information on ASEAN appears online at the ASEAN Website: www.asean.org The text of this publication may be freely quoted or reprinted, provided proper acknowledgement is given and a copy containing the reprinted material is sent to Public Outreach and Civil Society Division of the ASEAN Secretariat, Jakarta Copyright Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN) 2015. All rights reserved 2 (DVW$VLD6XPPLW'RFXPHQWV6HULHV East Asia Summit Documents Series 2005-2014 TABLE OF CONTENTS (Summit and Ministerial Levels Documents) 2005 Summit Chairman’s Statement of the First East Asia Summit, Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia, 14 December 2005 .................................................................................... 9 Kuala Lumpur Declaration on the East Asia Summit, Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia, 14 December 2005 ................................................................................... -

Download Regional Conference

ACKNOWLEDGMENT As ASEAN aspires to promote regional peace, stability and prosperity and become an effective community, there has been a relentless effort for the regional grouping to facilitate an even closer economic, political, social, and cultural cooperation. ASEAN also wishes to become a political and security community that is capable of managing regional tensions and preventing conflicts from flaring up. Notwithstanding positive developments, however, ASEAN still faces glaring challenges of both a traditional and non-traditional nature. These challenges include the unstoppable rise of China, the decline of the US and the deep flux of global institutional arrangements coupled with the ongoing territorial and sovereignty claims in the South China Sea. All of these pose serious uncertainty, as no one can predict the future of this region. As such, the Cambodian Institute for Cooperation and Peace feels that it is timely to organize a regional conference on “Cambodia and ASEAN: Managing Opportunity and Challenges beyond 2015 to determine how the future will hold for ASEAN. CICP would like to sincerely express deep appreciation to all the eminent speakers who are experts in their related fields from government officials and from other credible think-tanks in the region who have contributed their perspectives to address common challenges in the region of Southeast Asia, including Cambodia. CICP would also like to thank Mr. Rene Gradwohl, Country Representative of the Konrad- Adenauer Stiftung, for supporting the hosting of this regional conference and for the realization of this conference report which we hope will promote wider debates and interest on how ASEAN could revitalize its critical duties to deal with new challenges that have emerged.