Utilisation of Mineral Rent and the Diversified Growth of the Botswana Economy

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Makgadikgadi Framework Management Plan

Makgadikgadi Framework Management Plan Volume one: Main report November 2010 Republic of Botswana Makgadikgadi Framework Management Plan 2010 Report details This report is volume one of the Makgadikgadi Framework Management Plan prepared for the government by the Department of Environmental Affairs, Ministry of Environment, Wildlife and Tourism in partnership with the Centre for Applied Research. Volume one is the main plan for the Makgadikgadi area. Volume two contains detailed findings of specialist and component studies prepared during 2009/2010. Acknowledgements The MFMP project team is indebted to a large number of institutions, companies, persons and communities that have actively contributed to the projects through: 1. participation in various focus group discussions, project workshops/ meetings and kgotla meetings; 2. being interviewed for the livelihood survey or as a resource person; the provision of data and feedback on draft reports. We sincerely hope that the implementation of the plan will offer a ‘reward’ for these efforts and the time spent on the project. Citation: Department of Environmental Affairs and Centre for Applied Research, 2010. The Makgadikgadi Framework Management Plan. Government of Botswana, Gaborone. Volume one: main report 2 Makgadikgadi Framework Management Plan 2010 Contents List of Figures .......................................................................................................................................... 6 List of Tables .......................................................................................................................................... -

Dust Emission Response to Climate in Southern Africa Robert G

JOURNAL OF GEOPHYSICAL RESEARCH, VOL. 112, D09207, doi:10.1029/2005JD007025, 2007 Dust emission response to climate in southern Africa Robert G. Bryant,1 Grant R. Bigg,1 Natalie M. Mahowald,2 Frank D. Eckardt,3 and Simon G. Ross1 Received 22 December 2005; revised 12 October 2006; accepted 3 January 2007; published 9 May 2007. [1] The processes which act in mineral dust source regions and factors which contribute to interannual variability within dust plumes emanating from them are poorly understood. In this case study, we focus on processes modulating emissions of atmospheric mineral aerosols from a large ephemeral lake. We focus on one key ephemeral lake dust source in southern Africa, the Makgadikgadi Pans of Botswana. A range of satellite [for example, Total Ozone Mapping Spectrometer (TOMS), Moderate Resolution Imaging Spectrometer (MODIS)] and climate data (from meteorological stations and reanalysis data sources) are extracted and compared, highlighting initial problems (for example, data quality, calibration, record length) associated with long-term (10–20 years) monitoring of dust with regional sources in this and other dryland regions. Nevertheless, comparisons of satellite-retrieved inundation, mineral aerosols, vegetation abundance, and climate data for the 1980–2000 period suggest that desert dust loadings are intermittently influenced by the extent and frequency of lake inundation, sediment inflows, and surface wind speed variability. In addition, a significant proportion of the observed variability in the dust and hydrological cycle of this source could also be attributed to El Nin˜o-Southern Oscillation (ENSO) and Indian Ocean sea surface temperature anomalies. Both are known to have an important role in modulating rainfall variability in southern Africa. -

Botswana Update: SRK Review and Sampling Program

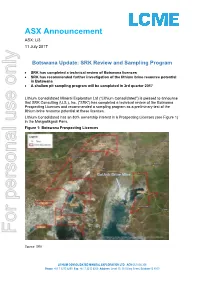

ASX Announcement ASX: Li3 11 July 2017 Botswana Update: SRK Review and Sampling Program • SRK has completed a technical review of Botswana licences • SRK has recommended further investigation of the lithium brine resource potential in Botswana • A shallow pit sampling program will be completed in 3rd quarter 2017 Lithium Consolidated Mineral Exploration Ltd (“Lithium Consolidated”) is pleased to announce that SRK Consulting (U.S.), Inc. (“SRK”) has completed a technical review of the Botswana Prospecting Licences and recommended a sampling program as a preliminary test of the lithium brine resource potential at these licences. Lithium Consolidated has an 80% ownership interest in 6 Prospecting Licenses (see Figure 1) in the Makgadikgadi Pans. Figure 1: Botswana Prospecting Licences BotAsh Brine Mine For personal use only Source: SRK LITHIUM CONSOLIDATED MINERAL EXPLORATION LTD ACN 612 008 358 Phone: +61 7 3212 6299 Fax: +61 7 3212 6250 Address: Level 10, 110 Mary Street, Brisbane Q 4000 Lithium Consolidated holds an 80% ownership interest in South Resource Ventures Pty Ltd, which has a direct interest in the Botswana project. Corsa All’Oro Pty Ltd holds the remaining 20% ownership interest in South Resource Ventures Pty Ltd. The Makgadikgadi Pans are in the Kalahari Desert, approximately 170 km west of Francistown and about 450 km north of Gaborone, the capital of Botswana. The Pans include the Ntwetwe and Sua Pans, to the west and east respectively. The regional and local geology indicate a potential for a mineral rich brine in the Makgadikgadi Pans area. This is supported by the long history of soda ash and salt production in the northern portion of the Sua Pan by Botswana Ash (Pty) Ltd. -

Using SLM to Improve the Integrity of the Makgadikgadi

United Nations Development Programme Country: Botswana PROJECT DOCUMENT1 Project Title: Using SLM to improve the integrity of the Makgadikgadi ecosystem and to secure the livelihoods of rangeland-dependent communities UNDAF Outcomes: By 2016 the rural poor, especially women, are deriving greater benefits from environment and natural ecosystems UNDP Strategic Plan Environment and Sustainable Development Primary Outcome: Growth and development are inclusive and sustainable, incorporating productive capacities that create employment and livelihoods for the poor and excluded UNDP Strategic Plan Secondary Outcome: Countries are able to reduce the likelihood of conflict and lower the risk of natural disasters, including from climate change Expected Country Programme Outcome(s): Strengthened capacity and improved policy and institutional framework for environmental management and sustainable development at the district (Boteti sub-district) and ecosystem-levels (Makgadikgadi wetland system); and Enhanced capacity of communities in southern Sua Pan (Mmea, Mokubilo, Mmatshumo and Mosu) for natural resources and ecosystem management and benefit distribution Expected CPAP Output(s): Evidence-based responsive policies, legislation, programmes and projects formulated by government to accelerate progress towards Vision 2016 goals. Implementing Partner: BirdLife Botswana, supported by the Department of Forestry and Range Resources and the Department of Environmental Affairs under the Ministry of Environment, Wildlife and Tourism 1For UNDP supported GEF funded projects as this includes GEF-specific requirements UNDP Environmental Finance Services Page 1 Brief Description A. Prevalent land and livestock management processes in Botswana’s Makgadikgadi ecosystem are likely to compromise the continued flow of ecosystem goods and services from the savannah ecosystem that are necessary to sustain the national economy, livelihoods and the rich fauna and flora diversity. -

Transportation and Economic Development in Botswana: a Case Study

TRANSPORTATION RESEARCH RECORD 1274 211 Transportation and Economic Development in Botswana: A Case Study A. V. LIONJANGA AND v. RAMAN The transport sector in Botswana has played an important role Transportation projects were oriented toward meeting the in economic gr wth in the 23 years following independence. The commercial and political interests of their owners. Because cOllntry has been fortunate in di covering natural resources to all of the owners were foreigners, they had no incentive to finance economic d velopments, and sound policies have ensured develop transportation in Botswana to assist in the country's that the transport sector grew at an affordable pace commensu rate with demands for services. The system of national planning development. The country's geographical and economic sit and project appraisals, major hi rorical developments in trnns uation, dispersed population, poor transportation infrastruc port, and policies that have evolved to encourngc future growth ture, and overwhelming dependence on neighboring states are highlighted. for transportation services made it imperative that Botswana develop the transport sector. Transportation was recognized as a service sector, that acted only as a catalyst and was rarely Botswana is a landlocked country in southern Africa sur the prime mover of growth. Nevertheless, improvements in rounded by Namibia in the west and northwest, Zambia and transportation were seen as prerequisites to stable population Zimbabwe in the north and northeast, and the Republic of growth and balanced economic development. South Africa on its remaining borders. A map of the country is shown in Figure 1. The country has a relatively large area of 582,000 km2; however, the Kgalagari desert constitutes 75 PLANNING IN BOTSWANA percent of the land mass and is largely uninhabitable. -

1 Introduction

Chapter 5 Wildlife Resources and Human Wildlife Conflict October 2010 Republic of Botswana Makgadikgadi Framework Management Plan 2010 Chapter details This chapter is part of the Project Development of a Makgadikgadi Framework Management Plan (MFMP) prepared for the Government by the Department of Environmental Affairs in partnership with the Centre for Applied Research. This chapter is authored by the following persons: Dr. Chris Brooks and Dr. G. Maude with inputs from Thoralf Meyer, Dr. Graham McCulloch and Dr. Jaap Arntzen Citation: Authors, 2010, Chapter title. In: Centre for Applied Research and Department of Environmental Affairs, 2010. Makgadikgadi Framework Management Plan. Volume 2, technical reports, Gaborone. Volume 2 - Chapter 5: Wildlife Resources and Human Wildlife Conflict Page ii Makgadikgadi Framework Management Plan 2010 Table of Contents 1 Introduction ........................................................................................................................1 1.1 Aims and Objectives .............................................................................................................. 1 1.2 Wildlife Diversity in the Makgadikgadi ................................................................................. 1 1.3 Human-Wildlife Conflict ........................................................................................................ 3 2 Approach, Methods and Activities .......................................................................................4 2.1 Approach .............................................................................................................................. -

BOTSWANA Gb 06

Botswana Gaborone key figures • Land area, thousands of km2 582 • Population, thousands (2005) 1 765 • GDP per capita, $ PPP valuation (2005/06) 10 755 • Life expectancy (2000-2005) 36.6 • Illiteracy rate (2005) 18.6 African Economic Outlook 2005-2006 www.oecd.org/dev/publications/africanoutlook All tables and graphs in this section are available in Excel format at: http://dx.doi.org/10.1787/535357406726 Botswana ZAMBIA ANGOLA rip riviSt Cap ! e Kasane hob C Windhoek O k av an go ZIMBABWE NAMIBIA ! Nata Bulawayo Maun Lake Ngami Sua ! Francistown ! Lake Xau Ghanzi Sh as Selebi- Phickwe hi KALAHARI DESERT po po m Li Sekoma GABORONE Jwaneng ! Kanye Johannesburg Tshabong Cape Town SOUTH AFRICA 0 100 km town > l million inhabitants major road main airport ! 500 000 - 1 000 000 secondary road secondary airport ! 100 000 - 500 000 railway commercial port < 100 000 track petroleum port fishing port SOUND MACROECONOMIC POLICIES and prudent use country in Africa and has the highest sovereign credit rating of diamond revenues have made Botswana one of the on the continent. To date, however, exports remain fastest-growing countries in the world over the last 25 overwhelmingly dependent on Serious long-term years, and it has now achieved middle-income status. diamonds and a few other minerals. development challenges Despite the government’s efforts, however, the economy Moreover, some structural reforms are remain despite current remains highly dependent on diamond exports, and the lagging behind, notably with regard to satisfactory growth. country continues to suffer from one of the highest privatisation and the labour market, HIV/AIDS infection rates in the world. -

CBD Fourth National Report Which Will Play an Important Role in Highlighting This

BOTSWANA FOURTH NATIONAL REPORT TO THE CONVENTION OF BIOLOGICAL DIVERSITY May 2009 BOTSWANA GOVERNMENT CONTENTS CONTENTS I EXECUTIVE SUMMARY ............................................................................................................................... VI CHAPTER 1 – OVERVIEW OF BIODIVERSITY STATUS, TRENDS AND THREATS ..........................1 1.1 INTRODUCTION ..............................................................................................................................1 1.2 THE OVERALL PICTURE ..................................................................................................................2 1.2.1 Botswana’s unique biodiversity.......................................................................................................2 1.2.1.1 Unique areas ............................................................................................................................................2 1.2.1.2 Important Bird Areas (IBAs) ...................................................................................................................5 1.2.1.3 Species diversity ......................................................................................................................................6 1.2.1.4 Agrobiodiversity ......................................................................................................................................7 1.2.2 Biodiversity conservation status......................................................................................................8 -

Makgadikgadi Birdlife 2011.Pdf

ENHANCING THE VALUE OF PROTECTED AREAS OF THE MAKGADIKGADI WETLAND SYSTEM THROUGH CO -MANAGEMENT AND SUSTAINABLE FINANCING Jane Turpie, Jon Barnes & Gwyn Wilson Final Report February 2011 ANCHOR environmental Cover photo and inside photos: J Turpie Enhancing the value of Protected Areas of the Makgadikgadi Pans Wetland System ii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS This study was funded by GEF as part of the GEF/UNDP/DWNP/BirdLife Botswana “Strategic Partnerships” project, and was managed by Pete Hancock of BirdLife Botswana. This report was produced by: Anchor Environmental Consultants , 8 Steenberg House, Silverwood Road, Tokai 7945, South Africa; www.anchorenvironmental.co.za ANCHOR environmental Design and Development Services , 25 Saffier Street, Eros Park, PO Box 25942 Windhoek, Namibia. Enhancing the value of Protected Areas of the Makgadikgadi Pans Wetland System iii EXECUTIVE SUMMARY Introduction This project forms part of the GEF/UNDP/DWNP/BirdLife Botswana PROJECT: “Strategic Partnerships to Improve the Financial and Operational Sustainability of Protected Areas”. The overall objective of the “Strategic Partnerships” project is to improve the financial and operational sustainability of Protected Areas (PAs) in Botswana through improved working partnerships between public, private, NGO and community stakeholders. This project aims to use the new CBNRM Policy, the draft Environmental Management Act and the Makgadikgadi Framework Management Plan in order to implement participatory planning and protected areas co-management, using the Makgadikgadi Wetland System, Makgadikgadi/Nxai National Park and the Flamingo Sanctuary as demonstration sites. Management of the small and fragmented system of protected areas in the Makgadikgadi area will only be sustainable and effective if numerous funding streams are tapped and benefits accrue to the adjacent communities. -

The Nature and Control of Organic Compounds in Soda Ash Evaporite

THE NATURE AND CONTROL OF ORGANIC COMPOUNDS IN SODA ASH EVAPORITE PRODUCTION THESIS Submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF SCIENCE of Rhodes University by PATRICIA MMONIEMANG MASEMOLA November 1999 TABLE OF CONTENTS Page TABLE OF CONTENTS ................................................. ii ABSTRACT ............................................................ v ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS .............................................. viii LIST OF FIGURES ...................................................... ix LIST OF TABLES ..................................................... xv ABBREVIATIONS .................................................... xviii CHAPTER 1: INTRODUCTION .......................................... 1 1.1 Solar evaporites ........................................ 1 1.1.1 Salt ............................................ 1 1.1.2 Soda Ash ........................................ 2 1.2 Solar salt-works ........................................ 4 1.3 Biological management of solar salt-works ................... 14 1.4. Sua Pan salt-works ..................................... 15 1.5 History of Sua Pan ..................................... 17 1.6 Process performance .................................... 22 1.7 Objectives ............................................ 24 CHAPTER 2: ISOLATION AND CHARACTERIZATION OF ORGANIC COMPOUNDS ............................................ 26 2.1 Introduction .......................................... 26 2.1.1 Organic contamination of Sua Pan soda ash ............. 27 -

The Makgadikgadi Basin, a Dynamic Hydrological Input and Aeolian Output System

The Makgadikgadi basin, a dynamic hydrological input and aeolian output system. Frank D. Eckardt a,* , Robert G. Bryant b, Warren W. Wood c, Kevin White d, Baruch Spiro e, Graham McCulloch f a Environmental and Geographical Sciences, U niversity of Cape T own, P Bag X3, Rondebosch, 7701, South Africa b Department of Geography, Uni versity of Sheffiel d, Dept. of Geography, Wi nter Street, Sheffiel d, S10 2TN, U K c Department of Geol ogical Sciences, Michigan State Uni versity, East Lansi ng, Michigan 48824, USA d Department of Geography, The Uni versity of R eading, Whiteknights, R eading, UK e Department of Miner alogy, The Natural Histor y Museum, Cromwell Road, London SW7 5BD, UK f Department of Z ool ogy, Uni versity of Dublin, Trinity College, Dublin 2, Irel and * Correspondi ng author: [email protected] This study focuses on modern day processes surrounding the Makgadikgadi pan basin system in NE Botswana. We present results on the chemistry and dynamics of fluvial surface water inputs, examine the nature and chemistry of various surface and subsurface evaporation products, provide data on the nature and chemistry of aeolian outputs and demonstrate the impact of aerosol deposition in the downwind sector of the pans. During the wet season surface water enters the saline pans and precipitates mostly calcite and halite, as well as dolomite and traces of other salts associated with the desiccation of the lake. The hypersaline subsurface brine (up to TDS 190,000 mg/l) is homogenous with minor variations due to pumping by BotAsh mine (Botswana Ash (Pty) Ltd), which extracts 2400 m 3 of brine/h from a depth of 38m. -

Aerosol Trace Metal Concentration And

AEROSOL TRACE METAL CONCENTRATION AND DISSOLUTION CHARACTERISTICS FROM KNOWN DUST EMITTERS IN SOUTHERN AFRICA KAUKURAUEE ISMAEL KANGUEEHI (BSC HONS EARTH SCIENCE) Thesis submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for the degree Master of Science (in Geology) at Stellenbosch University. SUPERVISOR: Dr Susanne Fietz CO-SUPERVISOR: Prof Frank Eckardt December 2017 DEPARTMENT OF EARTH SCIENCES Stellenbosch University https://scholar.sun.ac.za DECLARATION By submitting this report electronically, I declare that the entirety of the work contained therein is my own, original work, that I am the sole author thereof (save to the extent explicitly otherwise stated), that reproduction and publication thereof by Stellenbosch University will not infringe any third-party rights and that I have not previously in its entirety or in part submitted it for obtaining any qualification. Signature: Date: December 2017 Copyright © 2017 Stellenbosch University All rights reserved i Stellenbosch University https://scholar.sun.ac.za ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS First of all, I would like to thank my supervisor, Dr Susanne Fietz and my co-supervisor Prof Frank Eckardt for all the guidance, comments and suggestions during this project. I couldn’t have wished for better supervisors. In the same breath, I also want to thank Prof Roy, your comments and insight in this project is highly appreciated. Thank you for all the suggestions and discussions we had over the course of the project. I would also like to thank Johanna von Holdt for providing me with the samples used for the analytical experiments. I would also like to thank the NRF and NSFAF for financial assistance during this project, without this institutions, this project wouldn’t have been possible.