Using SLM to Improve the Integrity of the Makgadikgadi

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Makgadikgadi Framework Management Plan

Makgadikgadi Framework Management Plan Volume one: Main report November 2010 Republic of Botswana Makgadikgadi Framework Management Plan 2010 Report details This report is volume one of the Makgadikgadi Framework Management Plan prepared for the government by the Department of Environmental Affairs, Ministry of Environment, Wildlife and Tourism in partnership with the Centre for Applied Research. Volume one is the main plan for the Makgadikgadi area. Volume two contains detailed findings of specialist and component studies prepared during 2009/2010. Acknowledgements The MFMP project team is indebted to a large number of institutions, companies, persons and communities that have actively contributed to the projects through: 1. participation in various focus group discussions, project workshops/ meetings and kgotla meetings; 2. being interviewed for the livelihood survey or as a resource person; the provision of data and feedback on draft reports. We sincerely hope that the implementation of the plan will offer a ‘reward’ for these efforts and the time spent on the project. Citation: Department of Environmental Affairs and Centre for Applied Research, 2010. The Makgadikgadi Framework Management Plan. Government of Botswana, Gaborone. Volume one: main report 2 Makgadikgadi Framework Management Plan 2010 Contents List of Figures .......................................................................................................................................... 6 List of Tables .......................................................................................................................................... -

Utilisation of Mineral Rent and the Diversified Growth of the Botswana Economy

DEPARTMENT OF ECONOMICS UNIVERSITY OF STELLENBOSCH Utilisation of Mineral Rent and the Diversified Growth of the Botswana Economy By Thapelo Tebogo Moribame Thesis presented in fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Commerce (Economics) at the University of Stellenbosch Supervisor: Professor Colin McCarthy December 2011 University of Stellenbosch http://scholar.sun.ac.za Verklaring / Declaration 1 Ek erken dat die pleeg van plagiaat beteken dat ek iemand anders se werk as my eie aanbied en dat dit 'n oortreding is. Ek verstaan ook dat direkte vertalings plagiaat is. I agree that plagiarism means to present another’s work as my own and that it is an offence. I also understand that direct translations are plagiarism. 2 Dienooreenkomstig is alle aanhalings en bydraes vanuit enige bron (ingesluit die internet) volledig verwys (erken). Ek erken dat die woordelikse aanhaal van teks sonder aanhalingstekens (selfs al word die bron volledig erken) plagiaat is. Accordingly all quotations and contributions from any source whatsoever (including the internet) have been cited fully. I understand that the reproduction of text without quotation marks (even when the source is cited) is plagiarism. 3 Ek verklaar dat die werk in hierdie skryfstuk vervat my eie oorspronklike werk is en dat ek dit nie vantevore in die geheel of gedeeltelik ingehandig het vir bepunting in hierdie module of ‘n ander module nie. I declare that the work contained in this assignment is my original work and that I have not previously (in its entirety or in part) submitted it for grading in this module or another module. -

Luxury Botswana Safari Tours and Botswana Safaris

BOTSWANA Luxury Botswana Safari Tours Botswana Safaris Over the past 15 years, Botswana has emerged as one of the most exclusive and authentic safari destinations in southern Africa. Bolstered by a stable government committed to conservation of its precious wildlife areas, Botswana boasts a wide array of well regulated and preserved ecosystems making it the ideal country to plan your Luxury African safari tours. Two thirds of the land consists of arid Kalahari desert unsuitable for agriculture making for a unique African wildlife safari experience. Out of this desert landscape arises an incredible example of nature’s unpredictability: the Okavango Delta. Okavango Delta is a must for Luxury Botswana Safari Tours, fans out across Botswana’s north- western corner and creates a paradise of islands and lagoons teeming with birds and wildlife making it the ideal destination for a Botswana safari tour. In the northeast, the famous Chobe National Park supports great concentrations of Elephant and Buffalo making the ideal place for boating and land-based safaris. In the southeast the Tuli Block, supports some of Botswana’s only commercial farming along with magnificent game reserves and offers unique horseback riding safaris as well as cycling safaris. Linyanti Game Reserve lies to the northeast of the Okavango Delta famed for its huge herds of elephant. The bulk of the concession is comprised of different Mopane woodland associations, with a strip of riparian forest and floodplain. Looking for a unique and completely different Botswana safari experience? Visit Makgadikgadi Salt Pans to enjoy nature drives on the pans, quad biking adventures, visits to the regions gigantic Baobab trees, and up close encounters with real colonies of wild meerkats. -

Dust Emission Response to Climate in Southern Africa Robert G

JOURNAL OF GEOPHYSICAL RESEARCH, VOL. 112, D09207, doi:10.1029/2005JD007025, 2007 Dust emission response to climate in southern Africa Robert G. Bryant,1 Grant R. Bigg,1 Natalie M. Mahowald,2 Frank D. Eckardt,3 and Simon G. Ross1 Received 22 December 2005; revised 12 October 2006; accepted 3 January 2007; published 9 May 2007. [1] The processes which act in mineral dust source regions and factors which contribute to interannual variability within dust plumes emanating from them are poorly understood. In this case study, we focus on processes modulating emissions of atmospheric mineral aerosols from a large ephemeral lake. We focus on one key ephemeral lake dust source in southern Africa, the Makgadikgadi Pans of Botswana. A range of satellite [for example, Total Ozone Mapping Spectrometer (TOMS), Moderate Resolution Imaging Spectrometer (MODIS)] and climate data (from meteorological stations and reanalysis data sources) are extracted and compared, highlighting initial problems (for example, data quality, calibration, record length) associated with long-term (10–20 years) monitoring of dust with regional sources in this and other dryland regions. Nevertheless, comparisons of satellite-retrieved inundation, mineral aerosols, vegetation abundance, and climate data for the 1980–2000 period suggest that desert dust loadings are intermittently influenced by the extent and frequency of lake inundation, sediment inflows, and surface wind speed variability. In addition, a significant proportion of the observed variability in the dust and hydrological cycle of this source could also be attributed to El Nin˜o-Southern Oscillation (ENSO) and Indian Ocean sea surface temperature anomalies. Both are known to have an important role in modulating rainfall variability in southern Africa. -

LEROO LA TAU Makgadikgadi Pans National Park

LEROO LA TAU Makgadikgadi Pans National Park M10 B8 ZAMBIA T1 ANGOLA B8 Chobe Savanna Lodge Kasane C49 Livingstone Victoria ZAMBEZI NAMIBIA Chobe Game Lodge NATIONAL Falls Zambezi Region PARK Chobe River KASANE FOREST A33 RESERVE Kwando River CHOBE CHOBE FOREST RESERVE NATIONAL KWANDO PARK BOTSWANA Linyanti River ZIMBABWE Savute Safari Lodge LINYANTI SELINDA Savuti Channel OKAVANGO SAVUTI Savuti Marsh DELTA KHWAI Boteti River Xugana Island Lodge Camp Okavango Camp Xakanaxa Camp Moremi CHIEF’S Leroo La Tau Island MOREMI GAME A35 RESERVE OKAVANGO DELTA NXAI PAN NATIONAL PARK Makgadikgadi Maun PANS National Boteti River A3 A3 PARK Leroo La Tau Lake Ngami BOTSWANA MAKGADIKGADI PANS NATIONAL PARK Makgadikgadi Pan Leroo La Tau is situated on the western bank of the Boteti River, northwest of Khumaga Village and about 140 kilometers southeast of Maun. The eastern bank of the Boteti forms the boundary of the Makgadikgadi Pans National Park, which stretches away from the riverbank towards its interior of scrubland and mineral-rich grasslands. BOTSWANA The Best Safari Circuit in CHOBE GAME LODGE I SAVUTE SAFARI LODGE I CHOBE SAVANNA LODGE I CAMP OKAVANGO I XUGANA ISLAND LODGE I CAMP MOREMI I CAMP XAKANAXA I LEROO LA TAU THE CAMP FACILITIES 12 Luxurious thatched and glass-fronted chalets (can be arranged as double or single). ROOMS Accommodating a maximum of 24 guests. 1 Family Tent (2 en-suite bedrooms) available from March 2019 PILOT/GUIDE 1 x Pilot/Guide Room (not same standard as guest rooms). Fully inclusive of all meals, scheduled safari activities, local drinks (including RATES alcoholic drinks, excluding premium brands) and park entrance fees. -

Elephant Social Dynamics, Spatial Ecology and Human Elephant Conflict in the Makgadikgadi Salt Pans and Kalahari Ecosystems

Elephant Social Dynamics, Spatial Ecology and Human Elephant Conflict in the Makgadikgadi Salt Pans and Kalahari Ecosystems August 2009 Submitted to: Department of Wildlife and National Parks, Botswana Funded by: The San Diego Zoo and Elephants Without Borders Michael Chase Elephants Without Borders Po Box 682 Kasane Botswana Tel/Fax: ++267 6250202 Email: [email protected] PROJECT NARRATIVE Background Conservation management plans for wildlife species require accurate and reliable longitudinal information about population size, distribution, demography, reproductive rate and habitat use. However, obtaining detailed data is often hampered due to financial and time constraints imposed on local governments and scientists. Our fundamental aim in this segment of our elephant ecology study in the Kavango Zambezi TFCA is to augment the elephant conservation efforts of the Botswana Government by conducting research on the ecology of elephants in the Makgadikgadi and Kalahari ecosystems to identify factors regulating the spatiotemporal distribution and habitat use of elephants. Our ultimate goal is to share this information with appropriate authorities, communities and the scientific community, in order to mitigate Human Elephant Conflict (HEC) while simultaneously promoting the conservation of African elephants and their natural habitats in Botswana. Our study is unique and timely in that it monitors elephant range patterns in and out of national parks, across international boundaries and in habitats ranging from nearly desert to wetland/riverine environments. No other study has sought to conserve a “flagship” species by incorporating such a large and varied ecosystem. By adopting the most rigorous scientific methods and state-of- the- art techniques to derive estimates of elephant population size and distribution, as well as movement patterns across the region, we will greatly improve our understanding of the dynamic forces regulating elephant life histories, and their interactions with people thereby make significant contributions towards elephant conservation in Botswana. -

Mammal Movements & Migrations

AWF FOUR CORNERS TBNRM PROJECT : REVIEWS OF EXISTING BIODIVERSITY INFORMATION i Published for The African Wildlife Foundation's FOUR CORNERS TBNRM PROJECT by THE ZAMBEZI SOCIETY and THE BIODIVERSITY FOUNDATION FOR AFRICA 2004 PARTNERS IN BIODIVERSITY The Zambezi Society The Biodiversity Foundation for Africa P O Box HG774 P O Box FM730 Highlands Famona Harare Bulawayo Zimbabwe Zimbabwe Tel: +263 4 747002-5 E-mail: [email protected] E-mail: [email protected] Website: www.biodiversityfoundation.org Website : www.zamsoc.org The Zambezi Society and The Biodiversity Foundation for Africa are working as partners within the African Wildlife Foundation's Four Corners TBNRM project. The Biodiversity Foundation for Africa is responsible for acquiring technical information on the biodiversity of the project area. The Zambezi Society will be interpreting this information into user-friendly formats for stakeholders in the Four Corners area, and then disseminating it to these stakeholders. THE BIODIVERSITY FOUNDATION FOR AFRICA (BFA is a non-profit making Trust, formed in Bulawayo in 1992 by a group of concerned scientists and environmentalists. Individual BFA members have expertise in biological groups including plants, vegetation, mammals, birds, reptiles, fish, insects, aquatic invertebrates and ecosystems. The major objective of the BFA is to undertake biological research into the biodiversity of sub-Saharan Africa, and to make the resulting information more accessible. Towards this end it provides technical, ecological and biosystematic expertise. THE ZAMBEZI SOCIETY was established in 1982. Its goals include the conservation of biological diversity and wilderness in the Zambezi Basin through the application of sustainable, scientifically sound natural resource management strategies. -

Preliminary Checklist of the Plants of Botswana

PRELIMINARY CHECKLIST OF THE PLANTS OF BOTSWANA PRELIMINARY CHECKLIST OF THE PLANTS OF BOTSWANA by Moff at P. Setshogo Southern African Botanical Diversity Network Report No. 37 n 2005 Recommended citation format SETSHOGO, M.P. 2005. Preliminary checklist of the plants of Botswana. Southern African Botanical Diversity Network Report No. 37. SABONET, Pretoria and Gaborone. Produced by University of Botswana Herbarium Private Bag UB00704 Gaborone Botswana Tel. (267) 355 2602 Fax: (267) 318 5097 Published by Southern African Botanical Diversity Network (SABONET) c/o South African National Biodiversity Institute, Private Bag X101, 0001, Pretoria, South Africa and University of Botswana Herbarium, Private Bag UB00704, Gaborone. Printed in 2005 in the Republic of South Africa by Capture Press, Pretoria, (27) 12 349-1802. ISBN 1-919976-18-3 © 2005 SABONET. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means without the permission of the copyright holder. Editor-in-chief: Marthina Mössmer Subeditors: Lidia Gibson, Hanlie van Heerden & Cecilia de Vos Belgraver Text design and layout: Nicola Ellis (27) 82 878 9589 Cover design: Antoinette Burkhardt, Pretoria, South Africa (27) 82 909 0109 Photographs: M.P. Setshogo SABONET website: www.sabonet.org This report is a joint product of the University of Botswana Herbarium and the Southern African Botanical Diversity Network (SABONET) and was made possible through support provided by the Global Environment Facility (GEF)/ United Nations Development Programme (UNDP) and the United States Agency for International Development (USAID)/World Conservation Union-Regional Office for southern Africa (IUCN ROSA) (Plot no. -

Photo Safari Guide

Photo Safari Guide Guide to photographic safaris in Southern Africa Pangolin Photo Safaris | Photo Safari Guide 1 13 ANGOLA ZAMBIA 12 1 6 10 ZIMBABWE 2 7 4 NAMIBIA 3 5 BOTSWANA 8 9 SOUTH AFRICA 11 1 CHOBE 6 VICTORIA FALLS 11 CAPE TOWN 2 OKAVANGO DELTA 7 HWANGE 12 MANA POOLS 3 CENTRAL KALAHARI 8 MADIKWE 13 SOUTH LUANGWA 4 MAKGADIKGADI PANS 9 KRUGER / SABI SANDS 5 MASHATU 10 ETOSHA SOUTHERN AFRICA Most of our photo safaris take place in the beautiful photographic paradise that is Africa. Visit Botswana’s most iconic photographic destinations such as the Chobe National Park, the Makgadikgadi Pan and the Okavango Delta or visit Zimbabwe to witness and photograph one of the seven natural wonders of the world, the Victoria Falls. The Wildebeest Migration in the Masai Mara in Kenya is surely on everyone’s photographic bucket list and Namibia is a photographer’s dream with it’s vast open landscapes, massive sand dunes and spectacular deserts. Last but not least, visit South Africa which is a country that has it all. From the iconic reserves bordering Kruger, the beauty of The Garden route to the winelands and culture of Cape Town. For visa and embassy information for all countries visit www.projectvisa.com 2 Pangolin Photo Safaris | Photo Safari Guide PHOTOGRAPHIC ADVICE We decided to ask our resident photographic guides to share their advice on what to bring along on a photographic safari and so together with their recommendations we have collated this guide so that you get the very best advice and to ensure you have everything you need to have an unforgettable photo safari experience. -

Large Scale Conservation Planning and Priorities for the Kavango-Zambezi Transfrontier Conservation Area

Large Scale Conservation Planning and Priorities for the Kavango-Zambezi Transfrontier Conservation Area A report prepared for Conservation International by David H. M. Cumming August 2008 Disclaimer: The views and opinions expressed in this report are those of the author, except where otherwise referenced or accredited, and do not necessarily represent the views and opinions of Conservation International Large scale conservation planning - KAZA TFCA i EXECUTIVE SUMMARY The Kavango-Zambezi Transfrontier Conservation Area (KAZA TFCA) in southern central Africa covers an area of c. 400,0001 km2 – an area slightly larger than that of Zimbabwe, and 1.6 times the size of Great Britain. The Victoria Falls forms a well known central point in the TFCA and is near the meeting point of four of the five participating countries (Angola, Botswana, Namibia, Zambia, and Zimbabwe). Two major river basins, the Zambezi and the Okavango contribute major wetlands, including the Okavango Swamps, to the generally flat to gently undulating KAZA-TFCA landscapes. In palaeo-evolutionary terms the two basins are closely interlinked – a feature that has influenced the biodiversity of the area and which has important implications for wetland species and their conservation. KAZA encompasses globally significant wetlands and includes large areas of the Miombo- Mopane and the Kalahari-Namib Wilderness Areas. The region carries impressive populations of large mammals and birds, the largest elephant population in the world, two globally threatened large mammals (black rhinoceros and wild dog), several endemic species of plants, reptiles and amphibians, one endemic mammal and one endemic bird species. The TFCA includes a human population in the region 1.5 million people but large areas carry population densities of less than 5 people per km2. -

Botswana Update: SRK Review and Sampling Program

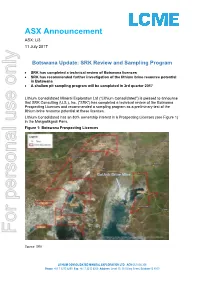

ASX Announcement ASX: Li3 11 July 2017 Botswana Update: SRK Review and Sampling Program • SRK has completed a technical review of Botswana licences • SRK has recommended further investigation of the lithium brine resource potential in Botswana • A shallow pit sampling program will be completed in 3rd quarter 2017 Lithium Consolidated Mineral Exploration Ltd (“Lithium Consolidated”) is pleased to announce that SRK Consulting (U.S.), Inc. (“SRK”) has completed a technical review of the Botswana Prospecting Licences and recommended a sampling program as a preliminary test of the lithium brine resource potential at these licences. Lithium Consolidated has an 80% ownership interest in 6 Prospecting Licenses (see Figure 1) in the Makgadikgadi Pans. Figure 1: Botswana Prospecting Licences BotAsh Brine Mine For personal use only Source: SRK LITHIUM CONSOLIDATED MINERAL EXPLORATION LTD ACN 612 008 358 Phone: +61 7 3212 6299 Fax: +61 7 3212 6250 Address: Level 10, 110 Mary Street, Brisbane Q 4000 Lithium Consolidated holds an 80% ownership interest in South Resource Ventures Pty Ltd, which has a direct interest in the Botswana project. Corsa All’Oro Pty Ltd holds the remaining 20% ownership interest in South Resource Ventures Pty Ltd. The Makgadikgadi Pans are in the Kalahari Desert, approximately 170 km west of Francistown and about 450 km north of Gaborone, the capital of Botswana. The Pans include the Ntwetwe and Sua Pans, to the west and east respectively. The regional and local geology indicate a potential for a mineral rich brine in the Makgadikgadi Pans area. This is supported by the long history of soda ash and salt production in the northern portion of the Sua Pan by Botswana Ash (Pty) Ltd. -

Partners in Biodiversity

AWF FOUR CORNERS TBNRM PROJECT : REVIEWS OF EXISTING BIODIVERSITY INFORMATION i Published for The African Wildlife Foundation's FOUR CORNERS TBNRM PROJECT by THE ZAMBEZI SOCIETY and THE BIODIVERSITY FOUNDATION FOR AFRICA 2004 PARTNERS IN BIODIVERSITY The Zambezi Society The Biodiversity Foundation for Africa P O Box HG774 P O Box FM730 Highlands Famona Harare Bulawayo Zimbabwe Zimbabwe Tel: +263 4 747002-5 E-mail: [email protected] E-mail: [email protected] Website: www.biodiversityfoundation.org Website : www.zamsoc.org The Zambezi Society and The Biodiversity Foundation for Africa are working as partners within the African Wildlife Foundation's Four Corners TBNRM project. The Biodiversity Foundation for Africa is responsible for acquiring technical information on the biodiversity of project area. The Zambezi Society will be interpreting this information into user-friendly formats for stakeholders in the Four Corners area, and then disseminating it to these stakeholders. THE BIODIVERSITY FOUNDATION FOR AFRICA (BFA is a non-profit making Trust, formed in Bulawayo in 1992 by a group of concerned scientists and environmentalists. Individual BFA members have expertise in biological groups including plants, vegetation, mammals, birds, reptiles, fish, insects, aquatic invertebrates and ecosystems. The major objective of the BFA is to undertake biological research into the biodiversity of sub-Saharan Africa, and to make the resulting information more accessible. Towards this end it provides technical, ecological and biosystematic expertise. THE ZAMBEZI SOCIETY was established in 1982. Its goals include the conservation of biological diversity and wilderness in the Zambezi Basin through the application of sustainable, scientifically sound natural resource management strategies.