OSHJR © 2018 1 No Darkies Sit in This Section of The

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Children of Stuggle Learning Guide

Library of Congress LIVE & The Smithsonian Associates Discovery Theater present: Children of Struggle LEARNING GUIDE: ON EXHIBIT AT THE T Program Goals LIBRARY OF CONGRESS: T Read More About It! Brown v. Board of Education, opening May T Teachers Resources 13, 2004, on view through November T Ernest Green, Ruby Bridges, 2004. Contact Susan Mordan, (202) Claudette Colvin 707-9203, for Teacher Institutes and T Upcoming Programs school tours. Program Goals About The Co-Sponsors: Students will learn about the Civil Rights The Library of Congress is the largest Movement through the experiences of three library in the world, with more than 120 young people, Ruby Bridges, Claudette million items on approximately 530 miles of Colvin, and Ernest Green. They will be bookshelves. The collections include more encouraged to find ways in their own lives to than 18 million books, 2.5 million recordings, stand up to inequality. 12 million photographs, 4.5 million maps, and 54 million manuscripts. Founded in 1800, and Education Standards: the oldest federal cultural institution in the LANGUAGE ARTS (National Council of nation, it is the research arm of the United Teachers of English) States Congress and is recognized as the Standard 8 - Students use a variety of national library of the United States. technological and information resources to gather and synthesize information and to Library of Congress LIVE! offers a variety create and communicate knowledge. of program throughout the school year at no charge to educational audiences. Combining THEATER (Consortium of National Arts the vast historical treasures from the Library's Education Associations) collections with music, dance and dialogue. -

100 Facts About Rosa Parks on Her 100Th Birthday

100 Facts About Rosa Parks On Her 100th Birthday By Frank Hagler SHARE Feb. 4, 2013 On February 4 we will celebrate the centennial birthday of Rosa Parks. In honor of her birthday here is a list of 100 facts about her life. 1. Rosa Parks was born on Feb 4, 1913 in Tuskegee, Alabama. ADVERTISEMENT Do This To Fix Car Scratches This car gadget magically removes scratches and scuffs from your car quickly and easily. trynanosparkle.com 2. She was of African, Cherokee-Creek, and Scots-Irish ancestry. FEATURED VIDEOS Powered by Sen Gillibrand reveals why she's so tough on Al Franken | Mic 2020 NOW PLAYING 10 Sec 3. Her mother, Leona, was a teacher. 4. Her father, James McCauley, was a carpenter. 5. She was a member of the African Methodist Episcopal church. 6. She attended the Industrial School for Girls in Montgomery. 7. She attended the Alabama State Teachers College for Negroes for secondary education. 8. She completed high school in 1933 at the age of 20. 9. She married Raymond Parker, a barber in 1932. 10. Her husband Raymond joined the NAACP in 1932 and helped to raise funds for the Scottsboro boys. 11. She had no children. 12. She had one brother, Sylvester. 13. It took her three tries to register to vote in Jim Crow Alabama. 14. She began work as a secretary in the Montgomery chapter of the NAACP in 1943. 15. In 1944 she briefly worked at Maxwell Air Force Base, her first experience with integrated services. 16. One of her jobs within the NAACP was as an investigator and activist against sexual assaults on black women. -

Monthly Celebrations & Causes

Monthly Celebrations & Causes National Drunk and Drugged Driving Prevention Month. Whichever holidays you celebrate this month, be aware of the dangers of driving under the influence of alcohol or drugs. Don’t let your holiday turn into a preventable tragedy. National Stress-Free Family Holiday Month. Don’t let your family drive The Accidental Origins of you crazy. Remember to make some quality time for family togetherness in the midst of the entire holiday bustle. Some Famous Products Tolerance Week, Dec. 1-7. A week dedicated to promoting the importance of Some well-known products and inventions tolerance and respect for people of different religions, races, and cultures. weren’t the result of careful research and planning. They were accidents that National Hand washing Awareness Week, Dec. 6-12. Sponsored by the someone with a creative mind spotted Henry the Hand Foundation, which seeks to raise awareness of the health some potential in. Imagine your life benefits of washing your hands to avoid the spread of disease. without . World AIDS Day, Dec 1. Devoted to sharing knowledge and understanding of Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndrome: how it’s contracted, how it can be In 1853, a chef named prevented, and how it affects people’s lives. • Potato chips. George Crum in Saratoga Springs, N.Y., Rosa Parks Day, Dec. 1. To celebrate the day in 1955 that Rosa Parks was grew frustrated by a diner who kept arrested for refusing to give up her seat to a white passenger on a bus in sending his potato crisps back, Montgomery, Ala. The day marked the birth of the modern U.S. -

Women in the Modern Civil Rights Movement

Women in the Modern Civil Rights Movement Introduction Research Questions Who comes to mind when considering the Modern Civil Rights Movement (MCRM) during 1954 - 1965? Is it one of the big three personalities: Martin Luther to Consider King Jr., Malcolm X, or Rosa Parks? Or perhaps it is John Lewis, Stokely Who were some of the women Carmichael, James Baldwin, Thurgood Marshall, Ralph Abernathy, or Medgar leaders of the Modern Civil Evers. What about the names of Septima Poinsette Clark, Ella Baker, Diane Rights Movement in your local town, city or state? Nash, Daisy Bates, Fannie Lou Hamer, Ruby Bridges, or Claudette Colvin? What makes the two groups different? Why might the first group be more familiar than What were the expected gender the latter? A brief look at one of the most visible events during the MCRM, the roles in 1950s - 1960s America? March on Washington, can help shed light on this question. Did these roles vary in different racial and ethnic communities? How would these gender roles On August 28, 1963, over 250,000 men, women, and children of various classes, effect the MCRM? ethnicities, backgrounds, and religions beliefs journeyed to Washington D.C. to march for civil rights. The goals of the March included a push for a Who were the "Big Six" of the comprehensive civil rights bill, ending segregation in public schools, protecting MCRM? What were their voting rights, and protecting employment discrimination. The March produced one individual views toward women of the most iconic speeches of the MCRM, Martin Luther King Jr.’s “I Have a in the movement? Dream" speech, and helped paved the way for the Civil Rights Act of 1964 and How were the ideas of gender the Voting Rights Act of 1965. -

December Calendar

December 2019 Spokane Area Diversity/Cultural Events National Universal Human Rights Month The Universal Declaration of Human Rights (UDHR) was adopted by the UN in 1948 as a response to the Nazi holocaust and to set a standard by which the human rights activities of all nations, rich and poor alike, are to be measured. The United Nations has declared an International Day for Elimination of Violence Against Women. From November 25th through December 10th, Human Rights Day, the 16 Days of Activism against Gender-Based Violence is to raise public awareness and mobilizing people everywhere to bring about change. The 2019 theme for the Elimination of Violence Against Women is ‘Orange the World: Generation Equality Stands Against Rape’. These dates were chosen to commemorate the three Mirabal sisters, who were political activists under Dominican ruler Rafael Trujillo (1930-1961) who ordered their brutal assassinate in 1960. Join the campaign! You can participate in person or on social media via the following hashtags: Use the hashtags: #GenerationEquality #orangetheworld and #spreadtheword. For more information, visit their website at http://www.un.org/en/events/endviolenceday/. ******************************************************************************** As Grandmother Taught: Women, Tradition and Plateau Art Coiled and twined basketry and beaded hats, pouches, bags, dolls, horse regalia, baby boards, and dresses alongside vintage photos of Plateau women wearing or alongside their traditional, handmade clothing and objects, with works by Leanne Campbell, HollyAnna CougarTracks DeCoteau Littlebull and Bernadine Phillips. Dates: August 2018 through December 2019 Time: Tuesday-Sunday, 10:00 am-5:00 pm Location: Northwest Museum of Arts and Culture, 2316 W. First Ave Cost: $10.00 adult, $8.00 seniors, $5.00 children ages 6-17, $8.00 college students with ID. -

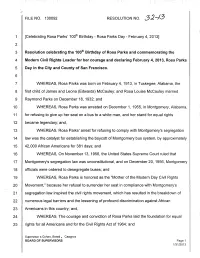

File No. 130092 Resolution No. 32.-13

II I I FILE NO. 130092 RESOLUTION NO. 32.-13 1 [Celebrating Rosa Parks' 100th Birthday - Rosa Parks Day - February 4, 2013] 2 3 Resolution celebrating the 100th Birthday of Rosa Parks and commemorating the 4 Modern Civil Rights Leader for her courage and declaring February 4, 2013, Rosa Parks 5 Day in the City and County of San Francisco. 6 7 WHEREAS, Rosa Parks was born on February 4, 1913, in Tuskegee, Alabama, the 8 first child of James and Leona (Edwards) McCauley; and Rosa Louise McCauley married 9 Raymond Parks on December 18, 1932; and 10 WHEREAS, Rosa Parks was arrested on December 1, 1955, in Montgomery, Alabama, 11 for refusing to give up her seat on a bus to a white man, and her stand for equal rights 12 became legendary; and, 13 WHEREAS, Rosa Parks' arrest for refusing to comply with Montgomery's segregation 14 law was the catalyst for establishing the boycott of Montgomery bus system, by approximately 15 42,000 African Americans for 381 days; and 16 WHEREAS, On November 13, 1956, the United States Supreme Court ruled that 17 Montgomery's segregation law was unconstitutional, and on December 20, 1956, Montgomery 18 officials were ordered to desegregate buses; and 19 WHEREAS, Rosa Parks is honored as the "Mother of the Modern Day Civil Rights 20 Movement," because her refusal to surrender her seat in compliance with Montgomery's 21 segregation law inspired the civil rights movement, which has resulted in the breakdown of 22 numerous legal barriers and the lessening of profound discrimination against African 23 Americans in -

The Travelin' Grampa

The Travelin’ Grampa Touring the U.S.A. without an automobile Special Supplement Christmastime Calendar Vol. 8, No. 12, December 2015 Illustration credits: Dec. 1891 Scribner’s magazine; engraving based on 1845 painting by Carl August Schwerdgeburth. Left: The First Christmas Tree, the Oak of Geismar, drawn by Howard Pyle, for a story by that title, by Henry van Dyke in Scribner’s Magazine, Dec. 1891. Pictured is Saint Boniface, in A.D. 772, directing Norsemen to where the tree is to be placed. Right: First Lighted Christmas Tree, said to have been in the home of Martin Luther, in 1510, or maybe 1535. Some scholars claim the first Christmas tree was put on display near Rega, in Latvia, in 1530. Or maybe near Tallinn, in Estonia, in 1510. In the USA, there’s more to Christmastime than Christmas Traveling abroad, Grampa notices most natives tend to resemble one another and share a similar culture. Not here in the USA. Our residents come in virtually every race, creed, skin color and geographic origin. In our country, at this time of year, we celebrate a variety of holidays, in a wide variety of ways. There’s the Feast of the Nativity, aka Christmas, of course. Most celebrate it Dec. 25; others on Jan. 6. Hindus celebrate their 5th day of Pancha Ganapati Dec. 25. There’s Chanukah. Or is it spelled Hanukkah? And let’s not forget Kwanzaa, several year- ending African American holidays invented in 1966 in Long Beach, Calif. Sunni Muslims say Mohammad’s birthday is Dec. 24 this year. -

The History That Inspired I Dream

GUIDE: THE HISTORY THAT INSPIRED I DREAM Title Sponsor of I Dream The Story of a Preacher from Atlanta A fusion of classical and popular musical traditions and Rhythm & Blues Table of Contents Douglas Tappin: Composer 3 Birmingham Beginnings 8 Introducing I Dream 4 Selma 9 Remembering Childhood 5 End of Dreams 10 Remembering College 6 Timeline 11 Montgomery Years 7 I Dream’s focus is the last 36 hours of Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr.’s life and a series of dreams, premonitions, and reminiscences all leading up to the April 4, 1968 assassination at the Lorraine Motel in Memphis, Tennessee. Statement of Intent It is important for us to reflect on our history. We can’t talk about where we want to go as a society without understanding where we’ve been. The intent of I Dream and the community dialogues surrounding the performances is to explore our society’s recent history and struggle for equality for all citizens by examining the life and legacy of Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. and his family, all of whom continue to provide inspiration, courage and hope for the future. I Dream is a work about yesterday for today. Douglas Tappin is a writer and composer who was born and educated in the United Kingdom. A former Commercial Attorney and member of the Honorable Society of Lincoln’s Inn, he practiced as a Barrister in England for eleven years. Tappin earned an additional postgraduate degree from Atlanta’s McAfee School of Theology, culminating in the dissertation That There Might Be Inspiration – a critical examination and articulation of transformative music-drama, including through the historical and contemporary works of Handel, Wagner, Puccini, Sondheim, Lloyd Webber and Rice, Boublil and Schönberg. -

Entry List Information Provided by Student Online Registration and Does Not Reflect Last Minute Changes

Entry List Entry List Information Provided by Student Online Registration and Does Not Reflect Last Minute Changes Junior Paper Round 1 Building: Hornbake Room: 0108 Time Entry # Affiliate Title Students Teacher School 10:00 am 10001 IA The Partition of India: Conflict or Compromise? Adam Pandian Cindy Bauer Indianola Middle School 10:15 am 10002 AK Mass Panic: The Postwar Comic Book Crisis Claire Wilkerson Adam Johnson Romig Middle School 10:30 am 10003 DC Functions of Reconstructive Justice: A Case of Meyer Leff Amy Trenkle Deal MS Apartheid and the Truth and Reconciliation Commission in South Africa 10:45 am 10004 NE The Nuremberg Trials to End a Conflict William Funke Roxann Penfield Lourdes Central Catholic School 11:00 am 10005 SC Edwards V. South Carolina: A Case of Conflict and Roshni Nandwani Tamara Pendleton Forestbrook Middle Compromise 11:15 am 10006 VT The Green Mountain Parkway: Conflict and Katie Kelley Susan Guilmette St. Paul's Catholic School Compromise over the Future of Vermont 11:30 am 10007 NH The Battle of Midway: The Turning Point in the Zachary Egan Chris Soule Paul Elementary School Pacific Theatre 11:45 am 10008 HI Gideon v. Wainwright: The Unfulfilled Promise of Amy Denis Kacey Martin Aiea Intermediate School Indigent Defendants' Rights 12:00 pm 10009 PA The Christmas Truce of 1914: Peace Brought by Drew Cohen Marian Gibfried St. Peter's School Soldiers, Not Governments 12:15 pm 10010 MN The Wilderness Act of 1964 Grace Philippon Catie Jacobs Twin Cities German Immersion School Paper Junior Paper Round 1 Building: Hornbake Room: 0125 Time Entry # Affiliate Title Students Teacher School 10:00 am 10011 AS Bloody Mary: A Catholic Who Refused To Liualevaiosina Chloe-Mari Tiana Trepanier Manumalo Academy - Compromise Leiato Elementary 10:15 am 10012 MS The Conflicts and Compromises of Lucy Maud Corgan Elliott Carolyn Spiller Central School Montgomery 10:30 am 10013 MN A Great Compromise: The Sherman Plan Saves the Lucy Phelan Phil Hohl Cyber Village Academy Constitutional Convention of 1787 10:45 am 10014 MI Gerald R. -

Friday, Jan. 1

Friday, Jan. 1 B = LIVE SPORTS MOVIES MOVIE PREMIERE EASTERN 4AM 4:30 5AM 5:30 6AM 6:30 7AM 7:30 8AM 8:30 9AM 9:30 10AM 10:30 11AM 11:30 CENTRAL 3AM 3:30 4AM 4:30 5AM 5:30 6AM 6:30 7AM 7:30 8AM 8:30 9AM 9:30 10AM 10:30 MOUNTAIN 2AM 2:30 3AM 3:30 4AM 4:30 5AM 5:30 6AM 6:30 7AM 7:30 8AM 8:30 9AM 9:30 PACIFIC 1AM 1:30 2AM 2:30 3AM 3:30 4AM 4:30 5AM 5:30 6AM 6:30 7AM 7:30 8AM 8:30 PREMIUM MOVIES Die Another Day (( (’02, Action) Pierce (:15) Mr. Mom ((6 (’83, Comedy) Michael (7:50) Tommy Boy (( (’95, WarGames ((( (’83, Suspense) Matthew (:25) Ghost SHO-E 318 Brosnan, Halle Berry ‘PG-13’ Keaton, Teri Garr ‘PG’ Comedy) Chris Farley ‘PG-13’ Broderick, Dabney Coleman ‘PG’ (’90) SHO-W 319 ¨Full Metal Jacket (’87) The Last of the Mohicans ((( (’92) ‘R’ Die Another Day (( (’02, Action) ‘PG-13’ (:15) Mr. Mom ((6 (’83, Comedy) ‘PG’ (10:50) Tommy Boy ¨Scary Stories to Tell (:05) Belushi (’20, Documentary) John Landis, (6:55) The Current War: Director’s (:40) Meet the Parents ((( (’00, Comedy) Meet the Fockers ((6 (’04, SHO2-E 320 in the Dark (’19) ‘PG-13’ Lorne Michaels ‘NR’ Cut (’19, Historical Drama) ‘PG-13’ Robert De Niro, Ben Stiller ‘PG-13’ Comedy) Robert De Niro ‘PG-13’ SHOBET 321 ¨She Hate Me (( (’04) ‘R’ Beneath a Sea of Lights (’20) Jim Sarbh ‘NR’ Against the Tide Surge (’20, Documentary) ‘NR’ (:15) The Express ((6 (’08, Biography) ‘PG’ SHOX-E 322 (:05) A Most Violent Year (’14) Oscar Isaac ‘R’ (:10) The Tuxedo (6 (’02, Comedy) ‘PG-13’ Top Gun ((( (’86, Action) Tom Cruise ‘PG’ Miami Vice (’06, Crime Drama) Colin Farrell ‘R’ SHOWTIME SHOS-E 323 -

Jeanne Theoharis a Life History of Being Rebellious

Want to Start a Revolution? Gore, Dayo, Theoharis, Jeanne, Woodard, Komozi Published by NYU Press Gore, Dayo & Theoharis, Jeanne & Woodard, Komozi. Want to Start a Revolution? Radical Women in the Black Freedom Struggle. New York: NYU Press, 2009. Project MUSE., https://muse.jhu.edu/. For additional information about this book https://muse.jhu.edu/book/10942 Access provided by The College Of Wooster (14 Jan 2019 17:21 GMT) 5 “A Life History of Being Rebellious” The Radicalism of Rosa Parks Jeanne Theoharis In all these years . it’s strange . but maybe not . nobody asks . about my life . if I have children . why I moved to Detroit . what I think . about what we tried . to do. Something needs to be said . about Rosa Parks . other than her feet . were tired. Lots of people . on that bus . and many before . and since . had tired feet . lots of people . still do . they just don’t know . where to plant them. Nikki Giovanni, “Harvest for Rosa Parks”1 On October 30, 2005, Rosa Parks became the first woman and second African American to lie in state in the U.S. Capitol. Forty thou- sand Americans—including President and Mrs. Bush—came to pay their respects. Thousands more packed her seven-hour funeral celebration at the Greater Grace Temple of Detroit and waited outside to see a horse- drawn carriage carry Mrs. Parks’s coffin to the cemetery.2 Yet what is com- monly known—and much of what was widely eulogized—about Parks is a troubling distortion of what actually makes her fitting for such a national tribute. -

Social Impact Campaign Report Here

SOCIAL IMPACT CAMPAIGN FINAL REPORT TABLE OF CONTENTS OVERVIEW 3 MESSAGING AND OBJECTIVES 4 CALLS TO ACTION 6 FAITH ENGAGEMENT 7 PARTNERSHIPS 8 SCREENINGS 10 SCREENING TOOLKIT AND RESOURCES 13 COMMUNICATIONS 14 TOWN HALL OVERVIEW 15 CAMPAIGN MAINTENANCE 16 APPENDIX 17 THE RAPE OF RECY TAYLOR SOCIAL IMPACT CAMPAIGN: FINAL REPORT 2 overview The social impact campaign for The Rape of Recy Taylor was designed to engage, educate, and activate the public around issues related to sexual violence against women and underscore the historical trauma faced by Black women during the Jim Crow South and still today. Since the launch of the Impact campaign on December 7th, 2018 at Abyssinian Baptist Church in Harlem, NY, the film and impact campaign have been inspiring individuals, organizations, houses of worship, and university campuses across the nation. It concluded with a special Odysssey Impact Live Town Hall during Sexual Assault Awareness Month in April 2020. During the campaign lifecycle, Odyssey Impact coordinated 100 impact screenings of the film. The Rape of Recy Taylor impact campaign acknowledged the disproportionate discrimination faced by Black female survivors of sexual assault. It empowered audiences to become vocal allies that spoke out against the structural racism that affects survivors of color. Audiences were asked to engage by hosting a screening of the film, organizing a day of service in honor of Recy Taylor, donating to a sexual assault prevention organization in Recy Taylor’s name, and/or spotlighting Recy Taylor in social media posts and publications. Ultimately, the campaign ensured that Recy Taylor’s story became a focal point of national conversation by providing a dedicated vehicle that uplifted her contributions to the civil and women’s rights movements.