Angels Against Virgins

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Tonbridge Castle and Its Lords

Archaeologia Cantiana Vol. 16 1886 TONBRIDGE OASTLE AND ITS LORDS. BY J. F. WADMORE, A.R.I.B.A. ALTHOUGH we may gain much, useful information from Lambard, Hasted, Furley, and others, who have written on this subject, yet I venture to think that there are historical points and features in connection with this building, and the remarkable mound within it, which will be found fresh and interesting. I propose therefore to give an account of the mound and castle, as far as may be from pre-historic times, in connection with the Lords of the Castle and its successive owners. THE MOUND. Some years since, Dr. Fleming, who then resided at the castle, discovered on the mound a coin of Con- stantine, minted at Treves. Few will be disposed to dispute the inference, that the mound existed pre- viously to the coins resting upon it. We must not, however, hastily assume that the mound is of Roman origin, either as regards date or construction. The numerous earthworks and camps which are even now to be found scattered over the British islands are mainly of pre-historic date, although some mounds may be considered Saxon, and others Danish. Many are even now familiarly spoken of as Caesar's or Vespa- sian's camps, like those at East Hampstead (Berks), Folkestone, Amesbury, and Bensbury at Wimbledon. Yet these are in no case to be confounded with Roman TONBEIDGHE CASTLE AND ITS LORDS. 13 camps, which in the times of the Consulate were always square, although under the Emperors both square and oblong shapes were used.* These British camps or burys are of all shapes and sizes, taking their form and configuration from the hill-tops on which they were generally placed. -

Welcome to Praxis Praxis South Events for 2018: He Church Exists to Worship God

Welcome to Praxis Praxis South Events for 2018: he church exists to worship God. Worship is the only activity of the Church Getting ready for the Spirit! Twhich will last into eternity. Speaker: the Rev’d Aidan Platten Bless your enemies; pray for those Worship enriches and transforms our lives. In Christ we An occasion to appreciate some of the last liturgical are drawn closer to God in the here and now. thoughts of the late Michael Perham. who persecute you: Worship to This shapes our beliefs, our actions and our way of life. God transforms us as individuals, congregations Sacraments in the Community mend and reconcile. and communities. Speaker: The Very Rev’d Andrew Nunn, Dean of Worship provides a vital context for mission, teaching Southwark and pastoral care. Good worship and liturgy inspires A day exploring liturgy in a home setting e.g. confession, and attracts, informs and delights. The worship of God last rites, home communion can give hope and comfort in times of joy and of sorrow. Despite this significance, we are often under-resourced Please visit our updated website for worship. Praxis seeks to address this. We want to www.praxisworship.org.uk encourage and equip people, lay and ordained, to create, to keep up-to-date with all Praxis events, and follow the lead and participate in acts of worship which enable links for Praxis South. transformation to happen in individuals and communities. What does Praxis do to offer help? Praxis offers the following: � training days and events around the country (with reduced fees for members and no charge for ordinands or Readers-in-training, or others in recognised training for ministry) � key speakers and ideas for diocesan CME/CMD Wednesday 1 November 2017 programmes, and resources for training colleges/courses/ 10.30 a.m. -

Lent, Holy Week and Easter

Lent, Holy Week and Easter Music of Faith, Songs of Scripture Music and song have always been at the heart of Christian faith and worship. Throughout the scriptures the community of the faithful have responded to the divine by singing and making music upon instruments of all kinds. This Lent, we will be reflecting on the music of our faith and the songs of scripture, the psalms, as a means of bringing us closer to God. We journey to the cross accompanied by songs of lament which deepen our prayer and we greet the resurrection with joyful songs of praise and thanksgiving. Here at Ely Cathedral we are offering a wide range of worship opportunities for prayer and reflection in our Lent, Holy Week and Easter Programme. We are delighted to welcome inspiring preachers, among them Malcolm Guite, Stuart Townend, Megan Daffern and Rowan Williams. We will be accompanied on our journey by our Cathedral Choirs and musicians. We hope that you will feel able to engage with the story of Christ’s passion and resurrection in many and various ways; growing in holiness and deepening their faith as we journey together through the season of Lent. ‘This is our story, this is our song’ Shrove Tuesday | 13 February | 6.30pm The Big Pancake Party and Pancake Race With live music from Ely Cathedral Octagon Singers and Ely Cathedral Community Choir. Come and enjoy the fun in our Big Pancake Race and Pancake Party where we will be raising money for the Church Urban Fund’s Food Poverty Campaign and eating away at hunger. -

Bexley Team News St Barnabas, Joydens Wood St James, North Cray St John the Evangelist, Bexley St Mary the Virgin, Bexley

Bexley Team News St Barnabas, Joydens Wood St James, North Cray St John the Evangelist, Bexley St Mary the Virgin, Bexley 4th July 2021 Issue 68 Fifth Sunday after Trinity The church buildings will have been St Mary’s 8.30 am Holy Communion thoroughly cleaned. As usual, face-masks 10.00 am Holy Communion MUST be worn (unless medically exempt) hand sanitiser will be used and social St James 9.30 am Holy Communion distancing of 2 Metres MUST be observed at St Barnabas 10.45am Holy Communion all times. Do not attend if you or a member St John’s 8.00 am Holy Communion of your household is shielding or vulnerable. The church doors will be open 10.00 am Holy Communion for ventilation, so dress accordingly. Wednesday 10.00 am Holy Communion Friday 10.00 am Livestreamed Holy Communion: www.facebook.com/stjohnsbexley Team Zoom Services and Worship material Saturday 3rd July NO Saturday Nightwatch Zoom Service Instead you are invited to join the Thanksgiving and Farewell service for Bp James at 3.00 pm which will be livestreamed from Rochester Cathedral Sunday 4thJuly please note the new time of 9.00 am Sunday Zoom Service Bexley Team Children’s Church Great news! Children’s Church is back and this week we are looking at the story of Ruth and Naomi. Please visit https://youtu.be/z471Z_B3TH0 For other resources and ideas please visit Diocese of Rochester | Family Worship in the Home (anglican.org) Bible Readings Ezekiel 2 v1-5 2 Corinthians 12 v2 – 10 Mark 6 v1-13 The Collect: Almighty and everlasting God, by whose Spirit the whole body of the Church is governed and sanctified: hear our prayer which we offer for all your faithful people, that in their vocation and ministry they may serve you in holiness and truth to the glory of your name; through our Lord and Saviour Jesus Christ, who is alive and reigns with you, in the unity of the Holy Spirit, one God, now and for ever. -

PDF 23Rd February Newsletter

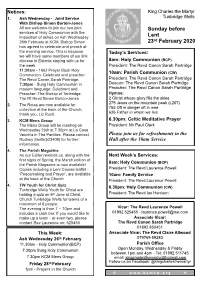

Notices: King Charles the Martyr 1. Ash Wednesday - Joint Service Tunbridge Wells With Bishop Simon Burton-Jones All are welcome to join our two joint Sunday before services of Holy Communion with the imposition of ashes on Ash Wednesday Lent 26th February at KCM. Bishop Simon 23rd February 2020 has agreed to celebrate.and preach at the evening service. This is because Today’s Services: we will have some members of our link diocese in Estonia staying with us for 8am: Holy Communion (BCP) the week. President: The Revd Canon Sarah Partridge 11:30am - 1662 Prayer Book Holy 10am: Parish Communion (CW) Communion: Celebrant and preacher: The Revd Canon Sarah Partridge. President: The Revd Canon Sarah Partridge 7:30pm - Sung Holy Communion in Deacon: The Revd Canon Sarah Partridge modern language: Celebrant and Preacher: The Revd Canon Sarah Partridge Preacher: The Bishop of Tonbridge, Hymns: The Rt Revd Simon Burton-Jones. 2 Christ whose glory fills the skies 279 Jesus on the mountain peak (t.207) 2. The Rotas are now available for 755 Oft in danger oft in woe collection at the back of the Church, 626 Father in whom we live thank you, Liz Ruch. 3. KCM Mens Group 6.30pm: Celtic Meditative Prayer The Mens Group will be meeting on President: Mr Paul Clark Wednesday 26th at 7.30pm at La Casa Vecchia in The Pantiles. Please contact Please join us for refreshments in the Rodney Smith(523409) for further Hall after the 10am Service information. 4. The Parish Magazine As our Editor reminds us, along with the Next Week’s Services: first signs of Spring, the March edition of 8am: Holy Communion (BCP) the Parish Magazine is now available! Copies including a Lent Course leaflet - President: The Revd Laurence Powell ‘Peacemaking and Prayer’, are available 10am: Family Service at the back of the Church President: The Revd Laurence Powell 4. -

No 57 October 1988 AD ASTRA PER ASPERA

THE rCOLFOAlSf f I folk «r 1 No 57 October 1988 AD ASTRA PER ASPERA October 1988 COLFEIAN the Chronicles of Colfe's School and of the Old Colfeians' Association The Master, Richard Scriven, planting a tree on the occasion of the Leathersellers' cricket match, 26th June, 1988 following the opening of the new Preparatory School on 23rd June. Mr Scriven's father laid the Foundation Stone for the Main School Building in 1964. ISSN 0010-0670 COVER DESIGN With a change in the format of the Colfeian, it was felt appropriate to change also the design of the cover.'The design chosen for this year at least, emphasises continuity. It is the design used on every issue from vol.1 no.l in December 1900 until vol.17 no. 67 in December 1939. In those days the Colfeian was the magazine of the Old Colfeians, while from 1902 the school had its own magazine, Colfensia. In 1951 the two magazines combined, thus beginning the present sequence of the Colfeian. The original cover, now being re-used, was designed by Charles J. Folkard whose signature it bears. More on this eminent Old Colfeian appears on another page. For his design, Folkard drew the heraldic stone which hung over the entrance to Colfe's Almshouses in Lewisham, depicting the arms of Abraham Colfe and the Leathersellers' Company. As a result of the school's celebration of Folkard this year, which accompanied the acquisition of some of his original drawings, the stone itself has been re-discovered. Since the demolition of the almshouses, it has lain, albeit somewhat damaged and begrimed in the vaults of Manor House, Lee. -

New Bishop of Rochester Announced

SHORTLANDS PARISHNEWS St. Mary’s, Shortlands endeavourstobringthelove ofGodintotheeverydaylives theSPAN ofthepeopleofShortlands. www.stmarysshortlands.org.ukwww.stmarysshortlands.org.uk August/September2010.Year30Number8 New BishopofRochesterannounced wider communities and their people His pastoral and leadership gifts, and seeing the things of God’s his concern for people and Kingdom grow.” communities, and his rich The Bishop of Norwich, the Right experience of ministry and mission Reverend Graham James said, "James in urban and rural settings will all Langstaff has been an outstanding be greatly appreciated. We much Bishop of Lynn. In just six years he look forward to welcoming him and has become greatly respected in the to working with him in Christ’s Diocese of Norwich and the wider name.” community alike. His people skills are Bishop James trained for the well reflected in both his pastoral ordained ministry at St John’s care and his extensive engagement College, Nottingham. He served his with social issues, especially related curacy in the Diocese of Guildford to housing. He has energy, before moving to the Diocese of intelligence and a wonderful Birmingham in 1986 as Vicar of lightness of touch in speaking of God Nechells. He served as Chaplain to and the gospel. We will miss him and the Bishop of Birmingham from Bridget enormously. The Diocese of 1996 - 2000 before being Rochester will soon discover its good appointed as Rector of Holy Trinity, fortune." Sutton Coldfield, also becoming The Right Reverend Dr Brian Area Dean of Sutton Coldfield in Castle, Bishop of Tonbridge said, “I 2002. While in Birmingham he am delighted that Bishop James is to developed a particular interest in be the next Bishop of Rochester. -

Minutes PDF 77 KB

TONBRIDGE AND MALLING BOROUGH COUNCIL COUNCIL MEETING Tuesday, 3rd November, 2015 At the meeting of the Tonbridge and Malling Borough Council held at Civic Suite, Gibson Building, Kings Hill, West Malling on Tuesday, 3rd November, 2015 Present: His Worship the Mayor (Councillor O C Baldock), the Deputy Mayor (Councillor M R Rhodes), Cllr Mrs J A Anderson, Cllr Ms J A Atkinson, Cllr M A C Balfour, Cllr Mrs S M Barker, Cllr M C Base, Cllr Mrs P A Bates, Cllr Mrs S Bell, Cllr R P Betts, Cllr T Bishop, Cllr P F Bolt, Cllr J L Botten, Cllr V M C Branson, Cllr Mrs B A Brown, Cllr T I B Cannon, Cllr M A Coffin, Cllr D J Cure, Cllr R W Dalton, Cllr M O Davis, Cllr Mrs T Dean, Cllr T Edmondston- Low, Cllr B T M Elks, Cllr Mrs S M Hall, Cllr S M Hammond, Cllr Mrs M F Heslop, Cllr N J Heslop, Cllr S R J Jessel, Cllr D Keeley, Cllr Mrs F A Kemp, Cllr S M King, Cllr D Lettington, Cllr Mrs S L Luck, Cllr B J Luker, Cllr D Markham, Cllr P J Montague, Cllr Mrs A S Oakley, Cllr L J O'Toole, Cllr M Parry-Waller, Cllr S C Perry, Cllr H S Rogers, Cllr R V Roud, Cllr Miss J L Sergison, Cllr T B Shaw, Cllr Miss S O Shrubsole, Cllr C P Smith, Cllr Ms S V Spence, Cllr A K Sullivan, Cllr M Taylor, Cllr F G Tombolis, Cllr B W Walker and Cllr T C Walker Apologies for absence were received from Councillors D A S Davis and R D Lancaster PART 1 - PUBLIC C 15/65 DECLARATIONS OF INTEREST There were no declarations of interest made in accordance with the Code of Conduct. -

Faithfulcross

FAITHFUL CROSS A HISTORY OF HOLY CROSS CHURCH, CROMER STREET by Michael Farrer edited by William Young ii FAITHFUL CROSS A HISTORY OF HOLY CROSS CHURCH, CROMER STREET by Michael Farrer edited by William Young, with additional contributions by the Rev. Kenneth Leech, and others Published by Cromer Street Publications, Holy Cross Church, Cromer Street, London WC1 1999 © the authors Designed by Suzanne Gorman Print version printed by ADP, London. The publishers wish to acknowledge generous donations from the Catholic League and members of the Regency Dining Club, and other donors listed in the introduction, which have made this book possible. iii Contents Foreword ..................................................................................................... vi Introduction .................................................................................................. 1 The Anglo-Catholic Mission ........................................................................ 5 Late Victorian Cromer Street ..................................................................... 17 Holy Cross and its Architect ...................................................................... 23 The Consecration ........................................................................................ 28 The Rev. and Hon. Algernon Stanley ........................................................ 33 The Rev. Albert Moore .............................................................................. 37 The Rev. John Roffey ................................................................................ -

Education Indicators: 2022 Cycle

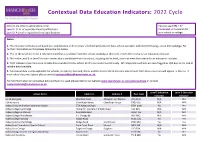

Contextual Data Education Indicators: 2022 Cycle Schools are listed in alphabetical order. You can use CTRL + F/ Level 2: GCSE or equivalent level qualifications Command + F to search for Level 3: A Level or equivalent level qualifications your school or college. Notes: 1. The education indicators are based on a combination of three years' of school performance data, where available, and combined using z-score methodology. For further information on this please follow the link below. 2. 'Yes' in the Level 2 or Level 3 column means that a candidate from this school, studying at this level, meets the criteria for an education indicator. 3. 'No' in the Level 2 or Level 3 column means that a candidate from this school, studying at this level, does not meet the criteria for an education indicator. 4. 'N/A' indicates that there is no reliable data available for this school for this particular level of study. All independent schools are also flagged as N/A due to the lack of reliable data available. 5. Contextual data is only applicable for schools in England, Scotland, Wales and Northern Ireland meaning only schools from these countries will appear in this list. If your school does not appear please contact [email protected]. For full information on contextual data and how it is used please refer to our website www.manchester.ac.uk/contextualdata or contact [email protected]. Level 2 Education Level 3 Education School Name Address 1 Address 2 Post Code Indicator Indicator 16-19 Abingdon Wootton Road Abingdon-on-Thames -

We Are Really Pleased to Welcome You Here

- - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - Every month we host a lunch to welcome people who are new to St Stephen’s and St Eanswythe’s. This is only - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - possible thanks to an amazing team of volunteer cooks. Sunday 9th June, 2.30pm to 5pm - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - We are currently looking for some new people to join To celebrate their move to Lincolnshire, Martyn and our team. If you can help or would like to know more please speak to Rachael. Jenny Burt will be holding a farewell afternoon tea on Sunday 9th June from 2.30pm to 5pm. This will be held at e. [email protected] or t. 01732 771977 Daphne and Stephen Mayles’ house in Pembury (Postillions, 2 Hastings Road, Pembury, Kent TN2 4PD). Parking is limited so please car share if possible. To help with catering please try and let Daphne or - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - Jenny know if you intend to come, but we would love to Occasionally we receive requests for tents from those see everyone, so it is ok to just turn up. who are homeless. If you have a spare tent, or if you attend any festivals this summer where there are tents e. [email protected] left behind at the end of the event, we would be really grateful to receive them. If you can help please speak to Sheila. - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - -

Maps -- by Region Or Country -- Eastern Hemisphere -- Europe

G5702 EUROPE. REGIONS, NATURAL FEATURES, ETC. G5702 Alps see G6035+ .B3 Baltic Sea .B4 Baltic Shield .C3 Carpathian Mountains .C6 Coasts/Continental shelf .G4 Genoa, Gulf of .G7 Great Alföld .P9 Pyrenees .R5 Rhine River .S3 Scheldt River .T5 Tisza River 1971 G5722 WESTERN EUROPE. REGIONS, NATURAL G5722 FEATURES, ETC. .A7 Ardennes .A9 Autoroute E10 .F5 Flanders .G3 Gaul .M3 Meuse River 1972 G5741.S BRITISH ISLES. HISTORY G5741.S .S1 General .S2 To 1066 .S3 Medieval period, 1066-1485 .S33 Norman period, 1066-1154 .S35 Plantagenets, 1154-1399 .S37 15th century .S4 Modern period, 1485- .S45 16th century: Tudors, 1485-1603 .S5 17th century: Stuarts, 1603-1714 .S53 Commonwealth and protectorate, 1660-1688 .S54 18th century .S55 19th century .S6 20th century .S65 World War I .S7 World War II 1973 G5742 BRITISH ISLES. GREAT BRITAIN. REGIONS, G5742 NATURAL FEATURES, ETC. .C6 Continental shelf .I6 Irish Sea .N3 National Cycle Network 1974 G5752 ENGLAND. REGIONS, NATURAL FEATURES, ETC. G5752 .A3 Aire River .A42 Akeman Street .A43 Alde River .A7 Arun River .A75 Ashby Canal .A77 Ashdown Forest .A83 Avon, River [Gloucestershire-Avon] .A85 Avon, River [Leicestershire-Gloucestershire] .A87 Axholme, Isle of .A9 Aylesbury, Vale of .B3 Barnstaple Bay .B35 Basingstoke Canal .B36 Bassenthwaite Lake .B38 Baugh Fell .B385 Beachy Head .B386 Belvoir, Vale of .B387 Bere, Forest of .B39 Berkeley, Vale of .B4 Berkshire Downs .B42 Beult, River .B43 Bignor Hill .B44 Birmingham and Fazeley Canal .B45 Black Country .B48 Black Hill .B49 Blackdown Hills .B493 Blackmoor [Moor] .B495 Blackmoor Vale .B5 Bleaklow Hill .B54 Blenheim Park .B6 Bodmin Moor .B64 Border Forest Park .B66 Bourne Valley .B68 Bowland, Forest of .B7 Breckland .B715 Bredon Hill .B717 Brendon Hills .B72 Bridgewater Canal .B723 Bridgwater Bay .B724 Bridlington Bay .B725 Bristol Channel .B73 Broads, The .B76 Brown Clee Hill .B8 Burnham Beeches .B84 Burntwick Island .C34 Cam, River .C37 Cannock Chase .C38 Canvey Island [Island] 1975 G5752 ENGLAND.