The Code of Hammurabi

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Art 258: Ancient and Medieval Art Spring 2016 Sched#20203

Art 258: Ancient and Medieval Art Spring 2016 Sched#20203 Dr. Woods: Office: Art 559; e-mail: [email protected] Office Hours: Monday and Friday 8:00-8:50 am Course Time and Location: MWF 10:00 – 10:50 HH221 Course Overview Art 258 is an introduction to western art from the earliest cave paintings through the age of Gothic Cathedrals. Sculpture, painting, architecture and crafts will be analyzed from an interdisciplinary perspective, for what they reveal about the religion, mythology, history, politics and social context of the periods in which they were created. Student Learning Outcomes Students will learn to recognize and identify all monuments on the syllabus, and to contextualize and interpret art as the product of specific historical, political, social and economic circumstances. Students will understand the general characteristics of each historical or stylistic period, and the differences and similarities between cultures and periods. The paper assignment will develop students’ skills in visual analysis, critical thinking and written communication. This is an Explorations course in the Humanities and Fine Arts. Completing this course will help you to do the following in greater depth: 1) analyze written, visual, or performed texts in the humanities and fine arts with sensitivity to their diverse cultural contexts and historical moments; 2) describe various aesthetic and other value systems and the ways they are communicated across time and cultures; 3) identify issues in the humanities that have personal and global relevance; 4) demonstrate the ability to approach complex problems and ask complex questions drawing upon knowledge of the humanities. Course Materials Text: F. -

Republic of Iraq

Republic of Iraq Babylon Nomination Dossier for Inscription of the Property on the World Heritage List January 2018 stnel oC fobalbaT Executive Summary .......................................................................................................................... 1 State Party .......................................................................................................................................................... 1 Province ............................................................................................................................................................. 1 Name of property ............................................................................................................................................... 1 Geographical coordinates to the nearest second ................................................................................................. 1 Center ................................................................................................................................................................ 1 N 32° 32’ 31.09”, E 44° 25’ 15.00” ..................................................................................................................... 1 Textural description of the boundary .................................................................................................................. 1 Criteria under which the property is nominated .................................................................................................. 4 Draft statement -

Gilgamesh Sung in Ancient Sumerian Gilgamesh and the Ancient Near East

Gilgamesh sung in ancient Sumerian Gilgamesh and the Ancient Near East Dr. Le4cia R. Rodriguez 20.09.2017 ì The Ancient Near East Cuneiform cuneus = wedge Anadolu Medeniyetleri Müzesi, Ankara Babylonian deed of sale. ca. 1750 BCE. Tablet of Sargon of Akkad, Assyrian Tablet with love poem, Sumerian, 2037-2029 BCE 19th-18th centuries BCE *Gilgamesh was an historic figure, King of Uruk, in Sumeria, ca. 2800/2700 BCE (?), and great builder of temples and ci4es. *Stories about Gilgamesh, oral poems, were eventually wriXen down. *The Babylonian epic of Gilgamesh compiled from 73 tablets in various languages. *Tablets discovered in the mid-19th century and con4nue to be translated. Hero overpowering a lion, relief from the citadel of Sargon II, Dur Sharrukin (modern Khorsabad), Iraq, ca. 721–705 BCE The Flood Tablet, 11th tablet of the Epic of Gilgamesh, Library of Ashurbanipal Neo-Assyrian, 7th century BCE, The Bri4sh Museum American Dad Gilgamesh and Enkidu flank the fleeing Humbaba, cylinder seal Neo-Assyrian ca. 8th century BCE, 2.8cm x 1.3cm, The Bri4sh Museum DOUBLING/TWINS BROMANCE *Role of divinity in everyday life. *Relaonship between divine and ruler. *Ruler’s asser4on of dominance and quest for ‘immortality’. StatuePes of two worshipers from Abu Temple at Eshnunna (modern Tell Asmar), Iraq, ca. 2700 BCE. Gypsum inlaid with shell and black limestone, male figure 2’ 6” high. Iraq Museum, Baghdad. URUK (WARKA) Remains of the White Temple on its ziggurat. Uruk (Warka), Iraq, ca. 3500–3000 BCE. Plan and ReconstrucVon drawing of the White Temple and ziggurat, Uruk (Warka), Iraq, ca. -

Hammurabi's Code

Hammurabi’s Code: Was It Just? Nearly 4,000 years ago, a man named Euphrates rivers. Hammurabi became king of a small city-state called Babylon. Today Babylon exists only as an After his victories at Larsa and Mari, archaeological site in central Iraq. But in Hammurabi's thoughts of war gave way to Hammurabi's time, it was the capital of the thoughts of peace. These, in turn, gave way to kingdom of Babylonia. thoughts of justice. In the 38th year of his rule, Hammurabi had 282 laws carved on a large, pillar- We know little about Hammurabi's like stone called a stele. Together, these laws have personal life. We don't know his birth date, how been called Hammurabi's Code. Historians believe many wives and children he had, or how and that several of these inscribed steles were placed when he died. We aren't even sure around the kingdom, though only what he looked like. However, one has been found intact. thanks to thousands of clay writing tablets that have been found by Hammurabi was not the first archaeologists, we know something Mesopotamian ruler to put his laws about Hammurabi's military into writing, but his code is the campaigns and his dealings with most complete. By studying his surrounding city-states. We also laws, historians have been able to know quite about every day life in get a good picture of many aspects Babylonia. of Babylonian society - work and family life, social structures, trade The tablets tell us that and government. For example, we Hammurabi ruled for 42 years. -

Neo Babylonian Rule

Neo Babylonians Rule “The Most Accomplished Empire” *Clears throat* Thank you. Thank you ever so much distinguished colleagues and professors for inviting me to speak to you today. As many of you know I'm professor Olivia Eichman of archeological studies at Stanford University. I have also worked at various dig sites in ancient sumers regions. All of these excavations lead me to countless degrees in antiquity. Enough about me already, I'm here to talk to you about about the great Mesopotamian Empires. But which empire was the greatest? Was it the Akkadians with the first empire? Or the Assyrians who reigned the longest? Neither of these empires strike me as the most accomplished. The Neo Babylonian’s Empire was the most accomplished empire by far and when you leave this room today I guarantee you will think as highly of them as I do too. Why do I think that the Neo Babylonians are the most accomplished? For starters, their ruler knew how to keep his empire safe. He had many safety precautions. One way Nebuchadrezzar II insured safety among his people was by surrounding their city in a wall so great in size two chariots could ride on it side by side. But that isn't all. No. Nebuchadnezzar II built another wall inside of the other wall for added protection. Both walls were named after Mesopotamian gods and goddesses. One of the gates that was built was called Ishtar gate, named after the goddess of war and love. To top it all off the walls were surrounded by a moat. -

The Evolution of Fragility: Setting the Terms

McDONALD INSTITUTE CONVERSATIONS The Evolution of Fragility: Setting the Terms Edited by Norman Yoffee The Evolution of Fragility: Setting the Terms McDONALD INSTITUTE CONVERSATIONS The Evolution of Fragility: Setting the Terms Edited by Norman Yoffee with contributions from Tom D. Dillehay, Li Min, Patricia A. McAnany, Ellen Morris, Timothy R. Pauketat, Cameron A. Petrie, Peter Robertshaw, Andrea Seri, Miriam T. Stark, Steven A. Wernke & Norman Yoffee Published by: McDonald Institute for Archaeological Research University of Cambridge Downing Street Cambridge, UK CB2 3ER (0)(1223) 339327 [email protected] www.mcdonald.cam.ac.uk McDonald Institute for Archaeological Research, 2019 © 2019 McDonald Institute for Archaeological Research. The Evolution of Fragility: Setting the Terms is made available under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial- NoDerivatives 4.0 (International) Licence: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/ ISBN: 978-1-902937-88-5 Cover design by Dora Kemp and Ben Plumridge. Typesetting and layout by Ben Plumridge. Cover image: Ta Prohm temple, Angkor. Photo: Dr Charlotte Minh Ha Pham. Used by permission. Edited for the Institute by James Barrett (Series Editor). Contents Contributors vii Figures viii Tables ix Acknowledgements x Chapter 1 Introducing the Conference: There Are No Innocent Terms 1 Norman Yoffee Mapping the chapters 3 The challenges of fragility 6 Chapter 2 Fragility of Vulnerable Social Institutions in Andean States 9 Tom D. Dillehay & Steven A. Wernke Vulnerability and the fragile state -

Terms and Facts- Hierarchical Scale

Terms and facts- Hierarchical scale From the Prehistoric and Neolithic- Post and Lintel, Megalith, tumulus, henge From Mesopotamia- The Code of Hammurabi, Shamash, Lamassu, Ziggurat, load bearing architecture, The Sumerians, the Akkadians, the Assyrians, the Babylonians, Stele or Stela From Minoa- Labrys, The myth of King Minos and the Minotaur From Mycenae- Corbelled vaults and domes, repousse, Tholos, Megaron, krater From Ancient Egypt- Ben-ben, mastaba, Imhotep, Ma’at, Canon (of artistic laws), cartouche, Canopic jars, Shabti or ushabti, the imagery of nine in connection to the pharaoh, the Amarna Period From Ancient Greece- Polykleitos, Humanism, contrapposto, Exekias, kouros and Kore, archaic smile, Praxiteles, some Greek mythology-especially the main gods and goddesses, meander (key design) Know the seven steps to lost wax casting Know the basic architecture of a Greek Temple-peristyle, the three column orders, (Doric, Ionic, Corinthian), stylobate, cella, shaft, caryatids, pediment, capital The two styles of Greek vase painting-black figure and red figure-the basic differences in look You should look up exam one of these myths and know the basic story or the main story about the character listed: Prometheus and Fire Apollo and Daphne Pygmalion and Galatea Niobe Persephone and Hades Pandora Tantalus-Son of Zeus The Danaides Alcyone and Ceyx Idas and Marpessa The Fall of Icarus Theseus and the Minotaur Perseus and the Medusa Jason and Medea Hercules and the Stymphalian Birds Chapter 2.9 Sculpture PART 2 MEDIA AND PROCESSES Seven steps in the lost-wax casting process Build and armature, sculpt the piece (clay), cover with ½ “ layer of wax, cover the entire piece with debris mixture, heat the entire work to melt out the wax through pre-drilled hole, pour the molten metal into the work through pre-drilled holes, break away the debris layer, clean and polishGateways to Art: Understanding the Visual Arts, Debra J. -

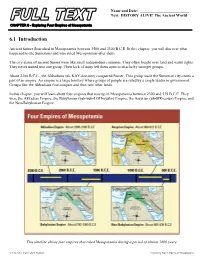

Text: HISTORY ALIVE! the Ancient World

Name and Date: _________________________ Text: HISTORY ALIVE! The Ancient World 6.1 Introduction Ancient Sumer flourished in Mesopotamia between 3500 and 2300 B.C.E. In this chapter, you will discover what happened to the Sumerians and who ruled Mesopotamia after them. The city-states of ancient Sumer were like small independent countries. They often fought over land and water rights. They never united into one group. Their lack of unity left them open to attacks by stronger groups. About 2300 B.C.E., the Akkadians (uh-KAY-dee-unz) conquered Sumer. This group made the Sumerian city-states a part of an empire. An empire is a large territory where groups of people are ruled by a single leader or government. Groups like the Akkadians first conquer and then rule other lands. In this chapter, you will learn about four empires that rose up in Mesopotamia between 2300 and 539 B.C.E. They were the Akkadian Empire, the Babylonian (bah-buh-LOH-nyuhn) Empire, the Assyrian (uh-SIR-ee-un) Empire, and the Neo-Babylonian Empire. This timeline shows four empires that ruled Mesopotamia during a period of almost 1800 years. © Teachers’ Curriculum Institute Exploring Four Empires of Mesopotamia Name and Date: _________________________ Text: HISTORY ALIVE! The Ancient World 6.2 The Akkadian Empire For 1,200 years, Sumer was a land of independent city-states. Then, around 2300 B.C.E., the Akkadians conquered the land. The Akkadians came from northern Mesopotamia. They were led by a great king named Sargon. Sargon became the first ruler of the Akkadian Empire. -

The Code of Hammurabi

The Code of Hammurabi The Original Version of this Text was Rendered into HTML by Jon Roland of the Constitution Society Converted to PDF by Danny Stone as a Community Service to the Constitution Society The Code of Hammurabi 1 The Code of Hammurabi hen Anu the Sublime, King of the Anunaki, and Bel, the lord of Heaven and earth, who Wdecreed the fate of the land, assigned to Marduk, the over-ruling son of Ea, God of righteousness, dominion over earthly man, and made him great among the Igigi, they called Babylon by his illustrious name, made it great on earth, and founded an everlasting kingdom in it, whose foundations are laid so solidly as those of heaven and earth; then Anu and Bel called by name me, Hammurabi, the exalted prince, who feared God, to bring about the rule of righteousness in the land, to destroy the wicked and the evil-doers; so that the strong should not harm the weak; so that I should rule over the black-headed people like Shamash, and enlighten the land, to further the well- being of mankind. Hammurabi, the prince, called of Bel am I, making riches and increase, enriching Nippur and Dur-ilu beyond compare, sublime patron of E-kur; who reestablished Eridu and purified the worship of E- apsu; who conquered the four quarters of the world, made great the name of Babylon, rejoiced the heart of Marduk, his lord who daily pays his devotions in Saggil; the royal scion whom Sin made; who enriched Ur; the humble, the reverent, who brings wealth to Gish-shir-gal; the white king, heard of Shamash, the mighty, who again laid the -

Justice in Ancient Mesopotamia Zchapter ONE JUSTICE in ANCIENT MESOPOTAMIA

Justice in Ancient Mesopotamia zCHAPTER ONE JUSTICE IN ANCIENT MESOPOTAMIA Introduction Any study of justice in the Bible must begin with ancient Mesopotamia be- cause the concept and the vocabulary of biblical justice are rooted in that culture. To uncover these roots, this chapter will explore justice in ancient Mesopotamia from the Sumerian culture to the Neo-Babylonian. Although the scope of this chapter seems ambitious, its purpose is limited. The structure of judicial power and the general administration of justice in these cultures will not be treated here.1 This chapter restricts itself rather to the analysis of certain aspects of justice: the problem of the poor and the oppressed, the action of the government in response to them, and the reflection of such a problem in popu- lar piety.2 The concept of justice in ancient Mesopotamia embraces a broader meaning than our concepts of commutative, distributive, or social justice. It is not enough for the governor to promulgate good laws and supervise the keeping of these laws; in order for justice to have its place in the Mesopotamian world, he must also issue decrees of mercy that allow the restoration of a destabilized equality. This chapter studies the texts in chronological order. After an overview of early social and economic development in ancient Mesopotamia, it analyzes the first of social reforms undertaken there. It then goes on to consider the various Mesopotamian law codes, the decrees of mercy (“justice”), and the religious texts that reflect the situation facing the underclasses of Mesopotamia.3 1 For a study of the characteristic structures of judicial power as well as the adminis- tration of justice in general within the societies of ancient Mesopotamia, see Hans J. -

Fertile Crescent.Pdf

Fertile Crescent The Earliest Civilization! Climate Change … For Real. ➢ Climate not what it is like today. ➢ In Ancient times weather was good, the soil fertile and the irrigation system well managed, civilisation grew and prospered. ➢ Deforestation - The most likely cause of climate changing in the fertile crescent. ➢ Massive forest have their weather patterns. Ground temperature is lower. More biodiversity. Today vs. Ancient Times Map of the Fertile Crescent A day in the fertile crescent. Rivers Support the Growth of Civilization Near the Tigris and Euphrates Surplus Lead to Societal Growth Summary Mesopotamia’s rich, fertile lands supported productive farming, which led to the development of cities. In the next section you will learn about some of the first city builders. Where was Mesopotamia? How did the Fertile Crescent get its name? What was the most important factor in making Mesopotamia’s farmland fertile? Why did farmers need to develop a system to control their water supply? In what ways did a division of labor contribute to the growth of Mesopotamian civilization? How might running large projects prepare people for running a government? Early Civilizations By Rivers. Mesopotamia The land between the rivers. Religion: Great Ideas: Great Men: Geography: Major Events: Cultural Values: Structure of the Notes! Farming Lead to Division of Labor Although Mesopotamia had fertile soil, Farmers could produce a food surplus, or farming wasn’t easy there. The region more than they needed.Farmers also used received little rain.This meant that the water irrigation to water grazing areas for cattle and levels in the Tigris and Euphrates rivers sheep. -

The Code of Hammurabi: an Economic Interpretation

International Journal of Business and Social Science Vol. 2 No. 8; May 2011 The Code of Hammurabi: An Economic Interpretation K.V. Nagarajan Department of Economics, School of Commerce and Administration Laurentian University, Sudbury Canada E-mail: [email protected], Fax: 705-675-4886 Introduction Hammurabi was the ruler of Babylon from 1792 B.C. to 1750 B.C1. He is much celebrated for proclaiming a set of laws, called the Code of Hammurabi (The Code henceforward). The Code was written in the Akkadian language and engraved on black diorite, measuring about two-and-a-quarter meters. The tablet is on display in the Louvre, Paris. The stone carving on which the laws are written was found in 1901-1902 by French archeologists at the Edomite capital Susa which is now part of the Kuzhisthan province in Iran. The Code was determined to be written circa 1780 B.C. Although there are other codes preceding it2, The Code is considered the first important legal code known to historians for its comprehensive coverage of topics and wide-spread application. It has been translated and analyzed by historians, legal and theological scholars (Goodspeed, 1902; Vincent, 1904; Duncan, 1904; Pfeiffer, 1920; Driver and Miles, 1952). The Code is well- known for embodying the principle of lex talionis (“eye for an eye”) which is described as a system of retributive justice. However, The Code is also much more complex than just describing offenses and punishments and not all punishments are of the retributive kind. The Code has great relevance to economists. However, very few studies have been undertaken from an economic or economic thought point of view.