Then and Now

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

ASMS Parish Profile

ALL SAINTS MARGARET STREET LONDON W1 APPOINTMENT OF FOURTEENTH INCUMBENT THE PARISH PROFILE STATEMENT DESCRIBING THE CONDITIONS, NEEDS AND TRADITIONS OF THE PARISH JULY 2020 1 Two quotations from former Parish Priests of All Saints relevant today: Henry Falconer Barclay Mackay – Fifth Vicar 1908 – 1934 “What is All Saints’, Margaret Street? It is a parish church in very little more than name. Few people and scarcely any Church People live in the tiny district, full now of day workrooms and wholesale businesses, which is bounded by Mortimer Street on the north, Oxford Street on the south, Great Portland Street on the west, and which on the east does not even include the near side of Wells Street. From the first it was intended that All Saints’ should diffuse an urbi et orbi ministry. It was to be a rallying point for the Catholic movement in the Church of England.” Parish Paper for October 1919. Quoted by Fr Moses thirteenth Vicar of All Saints in the Parish Paper for October 2019. [In 1919 the population of the parish then was around 2,000; the population of the enlarged parish is now only around 300 people.] Kenneth Needham Ross – Eighth Vicar 1951 – 1969, on the Mission of All Saints “Early in this century All Saints’ was described by a well-known and sympathetic observer as an “extinct volcano”. Whether that was just or not, it certainly started erupting again under Mackay’s inspired leadership. The parish work might diminish and almost reach vanishing point, but the mission of All Saints Church to London as a whole increased. -

“All Fired Up” Le Monde De Merde

The Krewe du Vieux Presents PURPLE PROSE, YELLOW Le Monde de Merde JOURNALISM AND THE LUST Vol. 19, No. 1 January 30, 2010 Priceless FOR GREEN Krewe du Vieux Is “All Fired Up” Dr. John Will Light Krewe’s Fire KdV Parade Route and Firewalk the parade fires up at NEW ORLEANS – We didn’t start the Regionalism took on a new meaning, Royal Street Chartres & Marigny fire. But looking around the city and the as politicos in Jefferson, St. John and Royal Street country, the whole shithouse nearly did St. Tammany parishes demonstrated a go up in flames. burning desire to mimic the exploits of things really start to heat up here! Despite the best efforts of President our home-cooked (and half-baked) of- Chartres Street Yomama and Fed Chief Burned Hankey ficials. Many will soon be facing a trial Frenchmen Street (Indian casinos being about the only by fire. Street Toulouse Decatur Street the parade ends in a profitable enterprises around these Meanwhile, at City Hall… blaze of glory at Chartres & Elysian Fields Franklin Avenue days), the economy refused to rise from Chief Technology Punk Greg Meffert the ashes. The Cash for Clunkers pro- found himself smiling for the crime cam- gram netted only a small number of used eras. Recovery Czar Ed Blakely burned U.S. Congressmen, though we were every last bridge, but most people had Parade Route of the Krewe du Vieux, Saturday, January 30, 2010 at 6:30 PM pleased to see that former LA Rep. already decided it was extraneous com- citronellas of the Krewe will burn the Krewe of PAN, Mystic Krewe of Dollar Bill Jefferson was one of them. -

The Parish of All Saints with St John, Stamford

The Parish of All Saints with St John, Stamford Parish Profile 2019 www.stamfordallsaints.org.uk All Saints with St John Parish Profile 2019 1 WELCOME BY THE BISHOP OF GRIMSBY, The Rt. Revd Dr David Court Thank you for taking time to look at this particular post within the Diocese of Lincoln, As one of the largest diocese in the country stretching from the Humber estuary in the North to the Wash in the South we are home to a population of just over 1,000,000 people living a variety of different settings from the urban centres of Grimsby and Cleethorpes and Scunthorpe, the City of Lincoln, the market towns, the coastal strip, the new housing developments and the many, many small villages which mark our landscape. All are equally important to us, and all we are seeking to serve in making known the good news of Jesus that has been entrusted to us. In preparation for our recent ‘Peer Review’ we put together our diocesan mission and vision statements and summarised our intention as follows ‘Our aim then is to grow the Church, in both numbers and depth, through attention to what we see as our core tasks of faithful worship, confident discipleship and joyful service with the vision of being a healthy, vibrant, sustainable church which leads to transformed lives and communities across greater Lincolnshire making a difference in God’s world. To that end as a diocese we shall support, encourage and enable local parishes, benefices and mission communities to fulfil, within this framework, their own unique calling to serve in mission the community or communities in which they are set’. -

May 15-14 School News

ALL SAINTS ACADEMY: Saint Joseph 32 W MN St., St. Joseph, MN 56374 320-363-7505 ext. 150 Karl Terhaar, Principal May 15, 2014 e-mail: [email protected] EXTRAVAGANZA WE’RE ON THE LOOKOUT… EXTRAVAGANZA Auction Items are sought SATURDAY, MAY 31 for both the LIVE and SILENT Auctions! THEME: A NIGHT AT THE MOVIES ~ Great donations come from: Family, Friends, Come as your favorite movie character, actor or Neighbors, Co-workers. Do you have NEW actress! It will be a NIGHT TO REMEMBER~ items cluttering your closets that you may have College of St. Benedict – Field House. Featuring received as a gift or bought on clearance? How the FABULOUS ARMADILLOS! Tickets are about re-gifting them to us. No item is too still available! It will be a “block buster” hit! small (or too large!) Smaller items can be Do you have your babysitter yet? grouped together by our clever auction 5:30 – Doors Open 7:00 – Sit Down Dinner coordinators! What is your talent? GET 8:30 – Begins (around this time) CREATIVE… Host a Wine-Tasting party, 10:00 – Silent Auction Closes Gourmet Dinner party, Backyard BBQ, Dessert or Meal of the Month, Weekend at EXTRAGANZA VOLUNTEERS your Cabin, Week at your Time-share… Use We have very dedicated volunteers on our your imagination. The possibilities are Extravaganza Committee. They have put in endless! Do you own a business? We are countless hours to ensure that this event is a happy to advertise your business along with success. Your help is needed during the final your donation. -

IN MEMORIAM on the Feasts of All Saints and All Souls, We Pray For

IN MEMORIAM On the Feasts of All Saints and All Souls, we pray for those who have died in the past year. Rev. John Albrecht Lily Goss Donald Moses Elizabeth Hammond Beltz Elaine Gregersen R. J. Smith Gary Brown Anthony Eaton Haynes Fernella Sterling Letetia ‘Tish’ Brown Marjorie Keils Chris Strangland Harold Cherry Phil Keils Marjorie Maye Swanson Rosalind Clinton Betty Locke Esther Tietz Michael Daher Sally McIntosh Michael Thompson Graham Davis Barry Meda Nancy vom Steeg Sarah Jean Davis Brigitte Meide Gretchen Wilbert Raymond Joseph Deeb Loretta Meide Bob Williams Sarah Esse Pam Michael Marilyn Wittrup Dan Fead Joe Miller Fred Fead Patricia Moore We hold in our prayers those we love, whose spirits surround us on every side. Margaret Abbey Marvin & Verna Barber Keith Carter Ollie Abdalla Hugh F. Barrington, Sr. Alfred L. Carter, Jr. Hedy Meda Abdelnour Catherine Barthwell Michael Cathcart Delores Abdo Jack C. Barthwell, III Robert & Lillian Cherry Albert & Diane Abdullah Lindsey Barr Robert Christman Mary & Tony Abdullah Mary & William Basse Jon H. W. Clark Johanna Abdullah-Finn Forrest & Elsey Beck Romayne B. Clay Aliki Agopian Shirley Benzo Arthur Clinton Charles Alawan Rosalia Berendt Norton J. Cohen Katherine Daisy Albert Wanda Berendt Josephine (Younan) Cole Samuel Albert Donald Berlage Susan Cole Gary Ald Hugh S. Berrington Jr. Dr. Oliver S. Coleman John C. Ali Hugh & Grace Berrington Stanley Collins Dawson & Carrie Allen Emily O. Bigelow Rose Collins Edwin & Catherine Allen Seth Blumberg Peter Conti Floride Allen Bess Bonnier Kareem & Charles Costandi Jesse Allen Matthew Boudreaux Charles, Jamile, Norman Costandi Powell & Alma Allen Carolyn Briscoe Frances Boo Crofton Maya Angelou Loretta, Thomas & Nancy Briscoe Doyt Crouch Mrs. -

Newsletter 3

March 27, 2019 March 30 @ 6 p.m. 4ore! Golf Grille and Bar ALL SAINTS ALUM TO PROVIDE ENTERTAINMENT FOR SPRING EVENT Spring Benefit 2019 is almost here! We’ve made a few changes to the event plans, so here is the latest news. Looks like the West Texas weather may be chilly on Saturday night, so guests will party INSIDE the 4ore! Golf Grille and Bar. Put on your boots and come enjoy a cocktail reception from 6:00 - 7:00 p.m. A deli- cious steak dinner with all the trimmings will follow. We KNOW the Sweet Sixteen Tournament will be going and we all hope our Red Raiders will be playing! There are twenty-two screens inside the Grille to enjoy the games, so no worries about missing out. We’ll be recognizing three All Saints faculty members for their service: Dr. Glenn Davis and Missy Franklin for 21 years and Debbie Maines for 35 years. You won’t want to miss this year’s entertainment by Nashville Band, Moonlight Social. All Saints alumnus, Jeremy Burchard is bringing his talents back home to entertain the Patriots with his band’s contemporary mix of rock, country and pop. Don’t miss your chance to hear this talented band while enjoying a great evening with friends and supporting the mission of our school. A few tickets are still available. For more information contact Dawndi Higgins: 745-7701 or [email protected] Giddy Up Package Take your dancin’ party on the road to the 2019 Cattle Baron’s Ball! Package Includes: PLC PARKING SPACE • Two Baron’s Tickets ALL SAINTS CIRCLE DRIVE Enjoy the convenience of Honor your family or a loved one to the 2019 Lubbock reserved parking at the Cattle Baron’s Ball by naming the All Saints Circle on July 27. -

Liturgy Template

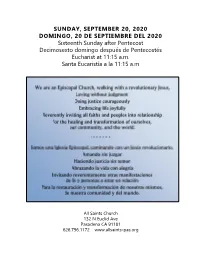

SUNDAY, SEPTEMBER 20, 2020 DOMINGO, 20 DE SEPTIEMBRE DEL 2020 Sixteenth Sunday after Pentecost Decimosexto domingo después de Pentecostés Eucharist at 11:15 a.m. Santa Eucaristía a la 11:15 a.m All Saints Church 132 N Euclid Ave Pasadena CA 91101 626.796.1172 www.allsaints-pas.org 1 ¡Bienvenidos! / Welcome! "Quienquiera que seas y dondequiera que te encuentres en el camino de la fe hay un lugar para ti aquí." “Whoever you are and wherever you find yourself on the journey of faith there is a place for you here.” Aprenda más sobre La Iglesia de Todos los Santos / Learn more about All Saints: https://allsaints-pas.org/welcome-to-asc/get-connected/ Las peticiones para una oración se pueden enviar llamando al 626.583.2707 para dejar un mensaje para la oficina de Pastoral o por correo electrónico a [email protected] o texto 910-839-8272 (910-TEXT-ASC) Prayer requests can be submitted by calling 626.583.2707 to leave a message for the Pastoral Care office or by email to [email protected] or text 901-TEXT-ASC or 901-839-8272 Nos unimos como comunidad amada en la Iglesia de Todos los Santos como una señal de lo que puede suceder fuera de nuestras puertas. Que podemos ser el cambio que nuestro mundo debe ver. Que podemos unirnos como una comunidad amada en Pasadena, la nación y el mundo. Que la familia humana puede estar unida y junta. Hoy. We Come Together as Beloved Community at All Saints Church as a sign of what can happen outside our doors. -

May 18, 2016 the Literary Magazine Is Here!

May 18, 2016 HIGH SCHOOL BACCALAUREATE AND GRADUATION All Lost and Found items The fi rst ever High School Baccalaureate and Graduation Ceremonies are this Fri- will be on display the day, May 20! Both mark the culmination of four years of hard work from twelve last week of school in the trailblazing seniors, as well as the prayers and work by countless hands to bring courtyard. Any leftover All Saints items will be the high school to life! Baccalaureate will take place during chapel on Friday at given back to the book- 8:00am. Our guest homilist will be The Rev. David Madison, Executive Director store and all other items of the Southwest Association of Episcopal Schools. Graduation will be Friday at will be donated. 5:30pm in Kirby Commons. Our commencement speaker will be Marsha Sharp. Seating will be very limited at both events. It promises to be a day of celebration On May 24, the Sixth and excitement! grade class will be tak- ing their Biography Pre- THE 2015-2016 GRADUATES OF ALL SAINTS EPISCOPAL SCHOOL sentations on the road to Jack Wyatt Brehmer Drew Jordan McCallister Wedgewood South Retire- ment community to share Mitchell Todd Davidson Michael David Sharp the residents there. Stu- Jamie Cheyenne Grace Garrett Alyssa Michelle Smith dents are encouraged to Matthew Gramm Harper Bryce Michael Smith wear their costumes. The Benjamin Noah Hays Benjamin Paul Tipton students are very excited Catherine Elizabeth Latour Keely Alexandra Umstot to share their research and projects! HIGH SCHOOL STATE TRACK RESULTS The All Saints High School Boys and Girls Track Teams earned third and fourth The Literary Magazine place fi nishes in the TAPPS 1A State Track Meet on May 6-7 in Waco. -

Saints Church

Our Mission Statement ALL SAINTS CHURCH In the spirit of Vatican II, All Saints Parish 1342 LANCASTER AVENUE is an o p e n and w e lco m ing C atho l ic SYRACUSE, NEW YORK 13210 (315) 472-9934 Chr i st i an Com m uni t y , joyfu l ly ground ed in A welcoming, diverse parish in the Catholic Tradition the Eucharist that strives to live the Gospel call to holiness and justice and loving Office Hours: Monday – Thursday 9am-2pm service to all. E-mail: [email protected] May 22 & 23, 2021 Pentecost Sunday Scripture for this weekend: Acts 2:1-11; Psalm 104; 1 Cor 12: 3b-7, 12-13; Jn 20:19-23 Scripture for next weekend: Dt. 4:32-34; Ps 33:4-5; Rom 8:14-17; Mt 28:16-20 COVID-19 Vaccine Clinic at All Saints! We are excited to be partnering with the County Department of Health and Wegmans to offer a Moderna COVID-19 vaccine clinic this Sunday, May 23rd from 10am to 2 pm at All Saints Parish! As a Roman Catholic Parish, we are pleased to join in the mission of getting the greatest number of folks in our wider Community vaccinated – emphasizing how strongly The Church blesses the vaccines and strongly encourages All to be vaccinated! In a January interview for Italy's TG5 news program, Pope Francis said "I believe that morally everyone must take the vaccine. It is the moral choice because it is about your life but also the lives of others." Wegmans pharmacy operations manager, Brian Pompo shared “We are proud to have the opportunity to serve the community in this way and to provide another option for our customers to get vaccinated.” Wegmans will continue offering vaccine appointments at its pharmacies throughout the Syracuse region and plans to offer additional clinics. -

Sacred Heart Church All Saints Church St. Patrick S Church

T he Catholic Communities of Crown Point & Moriah All Saints Church Mineville Sacred Heart Church Crown Point M St. PatrickÊs Church R Port Henry ! " # A uvqhhyytrr hvvyyphyyriyrrq) s ur6yvtuuhqrt rhuvts r LITURGY SCHEDULE $$% &'() !"# CǓǐǘǏ PǐNJǏǕ % & '#(" )'( #*+,('-. / # !"#$%& 0(12# $ 3 # # 4 56 0 ## )#1 - # 7 56 #8 2 MǐǓNJǂlj *# 5 56 & ### / - # % !"#$%& 09 #: $$% &'() ! ) # -2 : ! ) ;## 12# % & ! *##'' '2(-20 :: ! ) <# ## '( )3 # AǍǍ GdžǏdžǓǂǕNJǐǏǔ WNJǍǍ CǂǍǍ Mdž BǍdžǔǔdžDž * R ,& #* , O , , P'/ 010)# * ,2 ,& #3 , , ,O P'011)#4 , # 5, #5 #6 #3 ,2 , O 7P* 2 4 8 ' 4 10$&,19:&20$: / :11)# 2 , O & # & & #3 , & , , , , O , ';20<$)#* , , # O , , #P μ *+(," !(-,./,01%.2(.3 !40("5(6(# ,43&(#&( !71"))0(78"0/9( "2&(6" ":/07341( 0(,+/;/<. 3(=3(5()")!(,+/>& ":-0#? !!1:!(!(>7(40/!/!.5&8.&(7(%13.271 & O , = R 3 #P?, , = , # , * ( / # 2 # 3 , 2 O * P = R , ,# 8 , , , #48,, , = * O ? A&# &, hands; and put out your hand, and place it in my side; do , #P * , , # O&; 7P= O3 -

Saints' Episcopal Day School Parent

All Saints’ Episcopal Day School Parent Handbook Revised 2016 209 West 27th Street Austin, Texas 78705 (512) 472-8866 Fax (512) 477-5215 [email protected] School Mission The Mission of All Saints’ Episcopal Day School is to encourage spiritual, intellectual, emotional, physical, and social development in children through a nurturing and guiding relationship with teachers and family; and to provide a developmentally balanced curriculum that fosters a love of learning and a teaching of Christian values and traditions. All Saints’ Episcopal Day School admits any child, regardless of race, color, national, sexual orientation, or ethnic origin. All Saints’ Episcopal Day School admits every child so long as an appropriate curriculum can be provided and so that each child can reap the greatest benefit possible. All Saints’ Episcopal Day School is a school where parents and visitors are welcome. We believe that a quality environment for children is one, which not only permits, but also encourages parents’ consistent involvement. All visitors during school hours, including parents, must sign in at the School. Please see the Visitor Policy on page 4. CONTENTS Philosophy Statement ......................................................................................................................1 School Session & Hours..................................................................................................................2 Before and After School Care .........................................................................................................3 -

Saints (TV Series) ÐÐ ºÑ‚ьор ÑÐ ¿Ð¸ÑÑ ŠÐº (Cast)

All Saints (TV series) ÐÐ ºÑ‚ьор ÑÐ ¿Ð¸ÑÑ ŠÐº (Cast) Jack Campbell https://bg.listvote.com/lists/film/actors/jack-campbell-6111556/movies Allison Cratchley https://bg.listvote.com/lists/film/actors/allison-cratchley-4732744/movies Wil Traval https://bg.listvote.com/lists/film/actors/wil-traval-6167381/movies Dan Feuerriegel https://bg.listvote.com/lists/film/actors/dan-feuerriegel-1190584/movies Natalie Saleeba https://bg.listvote.com/lists/film/actors/natalie-saleeba-6968234/movies Penne Hackforth-Jones https://bg.listvote.com/lists/film/actors/penne-hackforth-jones-7163398/movies Martin Lynes https://bg.listvote.com/lists/film/actors/martin-lynes-465020/movies Judith McGrath https://bg.listvote.com/lists/film/actors/judith-mcgrath-6303569/movies Tammy MacIntosh https://bg.listvote.com/lists/film/actors/tammy-macintosh-7681602/movies Grant Bowler https://bg.listvote.com/lists/film/actors/grant-bowler-2608802/movies Mark Priestley https://bg.listvote.com/lists/film/actors/mark-priestley-931712/movies Joy Smithers https://bg.listvote.com/lists/film/actors/joy-smithers-1710007/movies Ben Tari https://bg.listvote.com/lists/film/actors/ben-tari-4886545/movies Paul Tassone https://bg.listvote.com/lists/film/actors/paul-tassone-7153925/movies Ewen Leslie https://bg.listvote.com/lists/film/actors/ewen-leslie-5418987/movies Sam Healy https://bg.listvote.com/lists/film/actors/sam-healy-7407592/movies Jeremy Cumpston https://bg.listvote.com/lists/film/actors/jeremy-cumpston-6181268/movies Conrad Coleby https://bg.listvote.com/lists/film/actors/conrad-coleby-541827/movies