CURRICULUM 10Th Edition

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Song List 2012

SONG LIST 2012 www.ultimamusic.com.au [email protected] (03) 9942 8391 / 1800 985 892 Ultima Music SONG LIST Contents Genre | Page 2012…………3-7 2011…………8-15 2010…………16-25 2000’s…………26-94 1990’s…………95-114 1980’s…………115-132 1970’s…………133-149 1960’s…………150-160 1950’s…………161-163 House, Dance & Electro…………164-172 Background Music…………173 2 Ultima Music Song List – 2012 Artist Title 360 ft. Gossling Boys Like You □ Adele Rolling In The Deep (Avicii Remix) □ Adele Rolling In The Deep (Dan Clare Club Mix) □ Afrojack Lionheart (Delicious Layzas Moombahton) □ Akon Angel □ Alyssa Reid ft. Jump Smokers Alone Again □ Avicii Levels (Skrillex Remix) □ Azealia Banks 212 □ Bassnectar Timestretch □ Beatgrinder feat. Udachi & Short Stories Stumble □ Benny Benassi & Pitbull ft. Alex Saidac Put It On Me (Original mix) □ Big Chocolate American Head □ Big Chocolate B--ches On My Money □ Big Chocolate Eye This Way (Electro) □ Big Chocolate Next Level Sh-- □ Big Chocolate Praise 2011 □ Big Chocolate Stuck Up F--k Up □ Big Chocolate This Is Friday □ Big Sean ft. Nicki Minaj Dance Ass (Remix) □ Bob Sinclair ft. Pitbull, Dragonfly & Fatman Scoop Rock the Boat □ Bruno Mars Count On Me □ Bruno Mars Our First Time □ Bruno Mars ft. Cee Lo Green & B.O.B The Other Side □ Bruno Mars Turn Around □ Calvin Harris ft. Ne-Yo Let's Go □ Carly Rae Jepsen Call Me Maybe □ Chasing Shadows Ill □ Chris Brown Turn Up The Music □ Clinton Sparks Sucks To Be You (Disco Fries Remix Dirty) □ Cody Simpson ft. Flo Rida iYiYi □ Cover Drive Twilight □ Datsik & Kill The Noise Lightspeed □ Datsik Feat. -

Staying the Course, Staying Alive – Coastal First Nations Fundamental Truths: Biodiversity, Stewardship and Sustainability

Staying the Course, Staying Alive coastal first nations fundamental truths: biodiversity, stewardship and sustainability december 2009 Compiled by Frank Brown and Y. Kathy Brown Staying the Course, Staying Alive coastal first nations fundamental truths: biodiversity, stewardship and sustainability december 2009 Compiled by Frank Brown and Y. Kathy Brown Published by Biodiversity BC 2009 ISBN 978-0-9809745-5-3 This report is available both in printed form and online at www.biodiversitybc.org Suggested Citation: Brown, F. and Y.K. Brown (compilers). 2009. Staying the Course, Staying Alive – Coastal First Nations Fundamental Truths: Biodiversity, Stewardship and Sustainability. Biodiversity BC. Victoria, BC. 82 pp. Available at www.biodiversitybc.org cover photos: Ian McAllister (kelp beds); Frank Brown (Frank Brown); Ian McAllister (petroglyph); Ian McAllister (fishers); Candace Curr (canoe); Ian McAllister (kermode); Nancy Atleo (screened photo of canoers). title and copyright page photo: Shirl Hall section banner photos: Shirl Hall (pages iii, v, 1, 5, 11, 73); Nancy Atleo (page vii); Candace Curr (page xiii). design: Arifin Graham, Alaris Design printing: Bluefire Creative The stories and cultural practices among the Coastal First Nations are proprietary, as they belong to distinct families and tribes; therefore what is shared is done through direct family and tribal connections. T f able o Contents Foreword v Preface vii Acknowledgements xi Executive Summary xiii 1. Introduction: Why and How We Prepared This Book 1 2. The Origins of Coastal First Nations Truths 5 3. Fundamental Truths 11 Fundamental Truth 1: Creation 12 Fundamental Truth 2: Connection to Nature 22 Fundamental Truth 3: Respect 30 Fundamental Truth 4: Knowledge 36 Fundamental Truth 5: Stewardship 42 Fundamental Truth 6: Sharing 52 Fundamental Truth 7: Adapting to Change 66 4. -

MUSIC VIDEOS It Was Too Tough for Me to Choose Only 36 Music Videos from the Stash Archive and Compile Them Stash Media Inc

MUSIC VIDEOS It was too tough for me to choose only 36 music videos from the Stash archive and compile them Stash Media INC. Editor: STEPHEN PRice into this 2nd collection, so I did what any editor would do. I opened it up to let the best of the best Publisher: GReg ROBINS videos fight it out for victory in a totally gnarly, steel cage grudge match. Managing editor: HEATHER GRIEVE Associate publisher: MARILEE BOITSON Of course bets were placed on popular champions such as Kanye West’s “Welcome to Account managers: APRIL HARVEY, Heartbreak”, Radiohead’s “House of Cards”, and The Chemical Brothers’ “The Salmon Dance,” CHRISTINE STEAD Associate editor: ABBEY KERR but this year saw maniacal young bloods enter the ring with Flairs “Better Than Prince”, LeLe Business development: “Breakfast” and Wild Beasts “Brave Bulging Buoyant Clairvoyants”. And don’t forget the vicious PauliNE THomPsoN comebacks of seasoned prize-fighters like Grace Jones with “Corporate Cannibal” and Paul Music editor: STEVE MARCHESE Preview editor: McCartney with “222”, proving they still have the music video moves to make it to the top of our list. HEATHER GRIEVE Technical guidance: IAN HASKIN I know you’ll enjoy this new collection, just watch out for the blood spatter. MUSIC Heather Grieve Managing Editor Get your inspiration delivered monthly. VIDEOS Toronto, May 2009 Every issue of Stash DVD magazine [email protected] is packed with outstanding animation and VFX for design and advertising. Subscribe now: WWW.STASHMEDIA.TV ISSN 1712-5928 Subscrptions: www.stashmedia.tv. Submissions: www.stashmedia.tv/submit. Contact: Stash Media Inc. -

External Copyright Permission (If Applicable)

Music Our totally awesome music subbies and contributors have been working hard over the semester break to bring you the latest and greatest in music. We’ve got the goss on Splendour, reviews and interviews. So read on tune- loving friends, read on... Sparkadia You have probably heard of Sparkadia. A couple of months ago their debut album Postcards was featured on Triple J. They also recently completed a run of national dates stopping off in Adelaide to play a show with Perth’s the Dirty Secrets at Jive. At the moment they are probably still overseas having just played Glastonbury and T in the Park not to mention several other high profile festivals. I asked Alex, vocalist/guitarist, and Dave, drummer, how they felt about their recent run of good fortune. “It’s pretty sweet”, Dave confides. Of course it wasn’t always like this. “It’s been a real long hard slog and the combination of ‘a lot of luck and a lot of hard work’,” Alex tells me. The guys then explain how they spent nineteen hours in a tour van with The Cops to get to a show in Sydney, having just played in Adelaide. Inevitably, I got onto the subject of Sparkadia’s early days. Alex and Dave were school mates who only bonded over a love of Metallica and ‘Maiden. I gasped in the realisation that I had finally discovered One of the groups defining moments occurred at Splendour in the some like minded heavy metal fans. We spent a little time discussing Grass in 2003. -

Salvati Dal Rock and Roll

SENTIREASCOLTARE online music magazine GIUGNO N. 32 Wilco salvati dal rock and roll Hans Appelqvist King Kong Laura Veirs Valet Keren Ann Feist Low PelicanStars Of The Art Lid Of Fighting Smog I Nipoti Marino del CapitanoJosé Malagnino Cristina Zavalloni Parts & Labor Billy Nicholls Dead C The Sea And Cake Labrador Akoustic Desease Buffys eSainte-Marie n t i r e a s c o l t a r e WWW.AUDIOGLOBE.IT VENDITA PER CORRISPONDENZA TEL. 055-3280121, FAX 055 3280122, [email protected] DISTRIBUZIONE DISCOGRAFICA TEL. 055-328011, FAX 055 3280122, [email protected] MATTHEW DEAR JENNIFER GENTLE STATELESS “Asa Breed” “The Midnight Room” “Stateless” CD Ghostly Intl CD Sub Pop CD !K7 Nuovo lavoro per A 2 anni di distan- Matthew Dear, uno za dal successo di degli artisti/produt- critica di “Valende”, È pronto l’omonimo tori fra i più stimati la creatura Jennifer debutto degli Sta- del giro elettronico Gentle, ormai nelle teless, formazione minimale e spe- sole mani di Mar- proveniente da Lee- rimentale. Con il co Fasolo, arriva al ds. Guidata dalla nuovo lavoro, “Asa Breed”, l’uomo di Detroit, si nuovo “The Midnight Room”, sempre su Sub voce del cantante Chris James, voluto anche rivela più accessibile che mai. Sì certo, rima- Pop. Registrato presso una vecchia e sperduta da DJ Shadow affinché partecipasse alle regi- ne il tocco à la Matthew Dear, ma l’astrattismo casa del Polesine ed ispirato forse da questa strazioni del suo disco, la formazione inglese usuale delle sue produzioni pare abbia lasciato sinistra collocazione, il nuovo album si districa mette insieme guitar sound ed elettronica, ri- uno spiraglio a parti più concrete e groovy. -

The Chemical Brothers the Salmon Dance Mp3, Flac, Wma

The Chemical Brothers The Salmon Dance mp3, flac, wma DOWNLOAD LINKS (Clickable) Genre: Electronic / Hip hop Album: The Salmon Dance Country: US Released: 2007 Style: Big Beat, Pop Rap MP3 version RAR size: 1889 mb FLAC version RAR size: 1948 mb WMA version RAR size: 1733 mb Rating: 4.8 Votes: 702 Other Formats: VOX MP2 ASF ADX AA DTS APE Tracklist Hide Credits The Salmon Dance 1 3:57 Film Director – Dom & Nic Companies, etc. Made By – HIP Video Other versions Category Artist Title (Format) Label Category Country Year The The Salmon Freestyle CHEMSD26, CHEMSD26, Chemical Dance (CD, Dust, UK 2007 5099950339020 5099950339020 Brothers Single) Virgin The Salmon The Dance (Remixes) none Chemical Virgin none UK 2007 (CDr, Maxi, Brothers Promo) The Salmon The Dance (Edit) none Chemical Virgin none UK 2007 (CDr, Single, Brothers Promo) The Salmon The Dance (DVDr, none Chemical Virgin none UK 2007 DVD-V, Promo, Brothers PAL) The The Salmon Freestyle CHEMS26, CHEMS26, Chemical Dance (7", Single, Dust, UK 2007 5099950338979 5099950338979 Brothers Ltd, Hea) Virgin Related Music albums to The Salmon Dance by The Chemical Brothers The Chemical Brothers - Exit Planet Dust (CD Sampler Fête Du Disque) Electronic The Chemical Brothers - Swoon Electronic The Chemical Brothers - The Private Psychedelic Reel Electronic The Chemical Brothers - It Began In Afrika Electronic The Chemical Brothers - Do It Again Electronic The Chemical Brothers - Galvanize Electronic The Chemical Brothers - Out Of Control Electronic The Chemical Brothers - Let Forever Be / The Diamond Sky Electronic The Chemical Brothers - Battle Scars (Beyond The Wizards Sleeve Remix) Electronic / Rock The Chemical Brothers - Star Guitar Electronic. -

Gimme Mr Clubs

KEEPING RADIO RELEVANT FOR TOMORROW'S LISTENERS xclusive: Top Programming Minds PLUS Convene To Confront Youth And PPM: CHRISTIAN RADIO'S INTRO- Listening Recruitment DUCTION TO METERED RATINGS Challenges Is HD The Answe To Radio's 12 -24 Exodus? p.12 HD RADIO: CROSS- PROMOTING HD2 ON COMPANION WEB SITE I J1q_41 I.I1,711!I:4 \q'g0 ILight TWCandles: WXRT/Chicago, AIR TALENT: ONE MAN, COUNTLESS CHARACTERS KBCD /Denver, KFOG /San Francisco Celebrate Significant Triple A SYND1'''" -r` CRAFTY TECH- RADIO ET RECORDS Milestones p.18 NOLOGY + LOCALISM = SUCCESS SEPTEMBER 14, 2007 NO. 1727 $6.50 www.Radioand Records.con i ri Dear Jive Records, I can imagine you deal with a lot of pain in the ass PD's on a daily basis. Is it your goal to seek revenge on your stations? By releasing the new Britney scng my phone lines and entail have been full of nothing b_It outrageous comments from listeners. They say such things as, 'Play the Britney more YOU idiot! How cony you aren't playing the new Britney song right now? Why are you playing 'Beautiful Girls' AGAIN! We wan_ iiore Britney!, etc.' Stop torturing me! I'm already playing the crap out of it! Next time please release a stiff.' My IT dept is pissed. Phone lines are going down and my website is getting too many hits. 'Gimme More' records that my listeners won't like. This playing hits thing is getting aggravating." -nos Schuster/PD, WNVZ/Norfolk iiOne of the things that slakes Top 40 radio special is being able to mirror POP CULTURE. -

Salmon – the Lifeline to Our Culture”

The Development and Evaluation of “Salmon – the Lifeline to Our Culture” Curriculum Project By Gloria Alfred B.G.S., Simon Fraser University, 1997 A Project Submitted in Partial Fulfillment Of the Requirements for the Degree of MASTER OF EDUCATION in the Department of Curriculum and Instruction/Department of Education © Gloria Alfred, 2010 University of Victoria All rights reserved. This project may not be reproduced in whole or in part, by photocopy or other means, without the permission of the author. ii The Development and Evaluation of “Salmon – the Lifeline to Our Culture” Curriculum Project By Gloria Alfred B.G.S., Simon Fraser University, 1997 Supervisory Committee Dr. Gloria Snively, Supervisor (Department of Curriculum and Instruction) Dr. Lorna Williams, Departmental Member (Department of Curriculum and Instruction) iii Supervisory Committee Dr. Gloria Snively, Supervisor (Department of Curriculum and Instruction) Dr. Lorna Williams, Departmental Member (Department of Curriculum and Instruction) ABSTRACT This paper proposes a science curriculum that was aimed at making changes in the student awareness regarding our effect on the Pacific wild salmon of the Northwest Coast. It was geared at developing an understanding the importance the salmon is to our culture – our way of living. Another important task in which this particular curriculum focuses on was conservation strategies in which students developed on a personal level. Everything is connected and for sure as the world turns, our culture will surely diminish if the salmon -

Simplicity Two Thousand (M

ELECTRONICA_CLUBMUSIC_SOUNDTRACKS_&_MORE URBANI AfterlifeSimplicityTwoThousand AfterlifeSimplicityTwoThousand(mixes) AirTalkieWalkie Apollo440Gettin'HighOnYourOwnSupply ArchiveNoise ArchiveYouAllLookTheSameToMe AsianDubFoundationRafi'sRevenge BethGibbons&RustinManOutOfSeason BjorkDebut BjorkPost BjorkTelegram BoardsOfCanadaMusicHasTheRightToChildren DeathInVegasScorpioRising DeathInVegasTheContinoSessions DjKrushKakusei DjKrushReloadTheRemixCollection DjKrushZen DJShadowEndtroducing DjShadowThePrivatePress FaithlessOutrospective FightClub_stx FutureSoundOfLondonDeadCities GorillazGorillaz GotanProjectLaRevanchaDelTango HooverphonicBlueWonderPowerMilk HooverphonicJackieCane HooverphonicSitDownAndListenToH HooverphonicTheMagnificentTree KosheenResist Kruder&DorfmeisterConversionsAK&DSelection Kruder&DorfmeisterDjKicks LostHighway_stx MassiveAttack100thWindow MassiveAttackHits...BlueLine&Protection MaximHell'sKitchen Moby18 MobyHits MobyHotel PhotekModusOperandi PortisheadDummy PortisheadPortishead PortisheadRoselandNYCLive Portishead&SmokeCityRareRemixes ProdigyTheCastbreeder RequiemForADream_stx Spawn_stx StreetLifeOriginals_stx TerranovaCloseTheDoor TheCrystalMethodLegionOfBoom TheCrystalMethodLondonstx TheCrystalMethodTweekendRetail TheCrystalMethodVegas TheStreetsAGrandDon'tComeforFree ThieveryCorporationDJKicks(mix1999) ThieveryCorporationSoundsFromTheThieveryHiFi ToxicLoungeLowNoon TrickyAngelsWithDirtyFaces TrickyBlowback TrickyJuxtapose TrickyMaxinquaye TrickyNearlyGod TrickyPreMillenniumTension TrickyVulnerable URBANII 9Lazy9SweetJones -

The Chemical Brothers Star Guitar Mp3, Flac, Wma

The Chemical Brothers Star Guitar mp3, flac, wma DOWNLOAD LINKS (Clickable) Genre: Electronic Album: Star Guitar Country: UK Released: 2001 Style: House, Deep House, Big Beat MP3 version RAR size: 1626 mb FLAC version RAR size: 1843 mb WMA version RAR size: 1433 mb Rating: 4.7 Votes: 320 Other Formats: MP2 AC3 WMA MMF ADX AAC MIDI Tracklist Hide Credits 1 Star Guitar (Edit) 4:01 2 Star Guitar 6:54 Star Guitar (Pete Heller's Expanded Mix) 3 8:31 Engineer – Gary WilkinsonRemix – Pete Heller Star Guitar (Pete Heller's 303 Dub) 4 7:27 Engineer – Gary WilkinsonRemix – Pete Heller 5 Base 6 6:31 Credits Art Direction – Blue Source, The Chemical Brothers Artwork By [Screenprints] – Kate Gibb Engineer – Steve Dub Vocals – Beverley Skeete (tracks: 1 to 4) Other versions Title Category Artist Label Category Country Year (Format) The CHEMST14, 7243 Star Guitar Freestyle Dust, CHEMST14, 7243 UK & Chemical 2002 5 46169 6 9 (12", Single) Virgin 5 46169 6 9 Europe Brothers Star Guitar The (Short Radio Freestyle Dust, none Chemical none UK 2001 Edit) (CDr, Virgin Brothers Single, Promo) The Star Guitar ASW 38812, Astralwerks, ASW 38812, Chemical (CD, Single, US 2002 724383881222 Virgin 724383881222 Brothers Promo) The CHEMSD14, 7243 Star Guitar Freestyle Dust, CHEMSD14, 7243 Chemical Europe 2002 5 46169 2 1 (CD, Single) Virgin 5 46169 2 1 Brothers The Star Guitar VJCP-12153, 7243 Virgin, VJCP-12153, 7243 Chemical (CD, Maxi, Japan 2002 5 46169 2 1 Freestyle Dust 5 46169 2 1 Brothers Promo) Related Music albums to Star Guitar by The Chemical Brothers The -

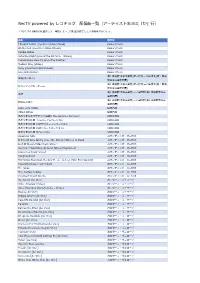

Rectv Powered by レコチョク 配信曲 覧(アーティスト名ヨミ「か」 )

RecTV powered by レコチョク 配信曲⼀覧(アーティスト名ヨミ「か」⾏) ※2021/7/19時点の配信曲です。時期によっては配信が終了している場合があります。 曲名 歌手名 I Predict A Riot [Live From Elland Road] Kaiser Chiefs Oh My God [Live From Elland Road] Kaiser Chiefs Golden Oldies Kaiser Chiefs Saturday Night [Live at the Fillmore - Stereo] Kaiser Chiefs People Know How To Love One Another Kaiser Chiefs Modern Way [Video] Kaiser Chiefs Ruby [Live From Elland Road] Kaiser Chiefs Record Collection Kaiser Chiefs 海上⾃衛隊 東京⾳楽隊,樋⼝好雄,三宅由佳莉(海上⾃衛 秋桜(コスモス) 隊東京⾳楽隊所属) 海上⾃衛隊 東京⾳楽隊,樋⼝好雄,三宅由佳莉(海上⾃衛 ビューティフル・ネーム 隊東京⾳楽隊所属) 海上⾃衛隊 東京⾳楽隊,三宅由佳莉(海上⾃衛隊東京⾳ 希望 楽隊所属) 海上⾃衛隊 東京⾳楽隊,三宅由佳莉(海上⾃衛隊東京⾳ 旅⽴ちの⽇に 楽隊所属) JUST LIVE MORE 鎧武乃風 YOUR SONG 鎧武乃風 あたりまえエクササイズ(英語)【No Surprise Exercise】 COWCOW あたりまえ体操 うちなーぐちバージョン COWCOW あたりまえ体操 DVDサラリーマンバージョン COWCOW あたりまえ体操 DVDショートバージョン1 COWCOW あたりまえ体操 冬バージョン COWCOW American Girls カウンティング・クロウズ If I Could Give All My Love -Or- Richard Manuel Is Dead カウンティング・クロウズ God Of Ocean Tides [Lyric Video] カウンティング・クロウズ She Don't Want Nobody Near [Closed Captioned] カウンティング・クロウズ Scarecrow [Lyric Video] カウンティング・クロウズ Hanginaround カウンティング・クロウズ Big Yellow Taxi (feat.ヴァネッサ・カールトン) [Non Film Version] カウンティング・クロウズ Possibility Days [Lyric Video] カウンティング・クロウズ Mr. Jones カウンティング・クロウズ Mrs. Potters Lullaby カウンティング・クロウズ You Can't Count On Me カウンティング・クロウズ Ay, Amor! [Ao Vivo] カエターノ・ヴェローゾ A Cor Amarela [Video] カエターノ・ヴェローゾ Amor Mais Que Discreto [Live - Video] カエターノ・ヴェローゾ Itapua [Ao Vivo] カエターノ・ヴェローゾ Eclipse Oculto [Ao Vivo] カエターノ・ヴェローゾ Capullito De Aleli [Ao Vivo] カエターノ・ヴェローゾ Carolina カエターノ・ヴェローゾ Cancao De Amor [Ao Vivo] カエターノ・ヴェローゾ Cucurrucucu -

Dancing Salmon: Human-Fish Relationships on the Northwest Coast

Dancing Salmon: Human-fish Relationships on the Northwest Coast by Deidre Sanders Cullon B.A., University of Victoria, 1993 M.A., University of Victoria, 1995 A Dissertation Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY in the Department of Anthropology © Deidre Sanders Cullon, 2017 University of Victoria All rights reserved. This dissertation may not be reproduced in whole or in part, by photocopy or other means, without the permission of the author. ii Supervisory Committee Dancing Salmon: Human-fish Relationships on the Northwest Coast by Deidre Sanders Cullon B.A., University of Victoria, 1993 M.A., University of Victoria, 1995 Supervisory Committee Dr. Ann Stahl, Department of Anthropology Co-Supervisor Dr. Brian Thom, Department of Anthropology Co-Supervisor Dr. John Lutz, Department of History Departmental Member iii Abstract Supervisory Committee Dr. Ann Stahl Department of Anthropology Dr. Brian Thom Department of Anthropology Dr. John Lutz Department of History With its myriad of relationships, my study considers the Laich-Kwil-Tach enlivened world in which multiple beings bring meaning and understanding to life. Through exploration of Laich-Kwil-Tach ontology I engage with the theoretical concepts of animism, historical ecology and political ecology, in what I call relational ecology. Here, I examine the divide between the relational world and what Western ontology considers a natural resource; fish. Through an analysis of ethnographic texts I work to elucidate the 19th-century human-fish relationship and through collaboration with Laich- Kwil-Tach Elders, based on Vancouver Island on the Northwest Coast of North America, I seek to understand how the 19th-century enlivened world informs 21st-century Laich- Kwil-Tach ontology.