Download Report In

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Positioning Women to Win to Guide Me Through the Challenging Issues That Arise During My Campaign for Re-Election.”

P o s i t ion i ng Wom e n to Wi n New Strategies for Turning Gender Stereotypes Into Competitive Advantages The Barbara Lee Family Foundation “Running my gubernatorial race was very different than running my previous race, and the Governor’s Guidebook series played an integral role in answering the questions I didn’t even know to ask. I will certainly rely on Positioning Women to Win to guide me through the challenging issues that arise during my campaign for re-election.” – Governor Christine Gregoire “Winning an election can never be taken for granted. The Governors Guidebook series arms both incumbents and first- time challengers with the “do’s” and “don’ts” of effectively communicating your achievements and vision. Leaders, regardless of gender, must develop a realistic and hopeful vision and be able to clearly articulate it to their supporters.” – Governor Linda Lingle P o s i t ion i ng Wom e n to Wi n New Strategies for Turning Gender Stereotypes Into Competitive Advantages DeDication Dedicated to the irrepressible spirit of the late Governor Ann Richards. acknowleDgements I would like to extend my deep appreciation to three extraordinary women who have served as Director at the Barbara Lee Family Foundation: Julia Dunbar, Amy Rosenthal and Alexandra Russell. I am also grateful for the support of the wonder women at “Team Lee”: Kathryn Burton, Moire Carmody, Hanna Chan, Monique Chateauneuf, Dawn Huckelbridge, Dawn Leaness, Elizabeth Schwartz, Mandy Simon and Nadia Berenstein. This guidebook would not have been possible without the vision and hard work of our political consultants and their staffs: Mary Hughes, Celinda Lake, Christine Stavem, Bob Carpenter and Pat Carpenter. -

March 19,2007 the Honorable Susan Combs Opinion No. GA-053 1

GREG ABBOTT March 19,2007 The Honorable Susan Combs Opinion No. GA-053 1 Texas Comptroller of Public Accounts Post Office Box 13528 Re: Application of section 103.001(b) of the Austin, Texas 7871 1-3528 Texas Civil Practice and Remedies Code to a claim filed by one of the Tulia defendants (RQ-0523-GA) Dear Comptroller Combs: Your predecessor in office requested an opinion on the interpretation of Texas Civil Practice and Remedies Code, section 103.OO 1(b).' Chapter 103 of the Civil Practice and Remedies Code provides for compensation to persons who have been wrongfully imprisoned. See TEX.CIV. PRAC. & REM. CODE ANN. ch. 103 (Vernon 2005). Claims for compensation are filed with the Comptroller's judiciary section. See id. 5 103.051 (a). Section 103.001(a) states the criteria for entitlement to compensation for wrongful imprisonment while section 103.001(b) provides the following restriction on entitlement to compensation under section 103.OO 1(a): (b) A person is not entitled to compensation under Subsection (a) for any part of a sentence in prison during which the person was also serving a concurrent sentence for another crime to which Subsection (a) does not apply. Id. 5 103.001 The question about section 103.OO 1(b) arose in connection with a wrongful imprisonment compensation claim filed by a Tulia defendant. The request letter recited the well-publicized facts of the Tulia prosecutions: In July 1999, 46 individuals, nearly all African Americans, were arrested in Tulia by a local drug task force and charged with the sale of small amounts of cocaine. -

EAST TEXAS COLLEGE TOUR Thursday, Nov 7, 2019 Events: Angelina College, Stephen F

EAST TEXAS COLLEGE TOUR Thursday, Nov 7, 2019 Events: Angelina College, Stephen F. Austin State University, Wiley College, Kilgore College, University of Texas at Tyler CONFIRMED CANDIDATES (listed alphabetically) Note: Tentative list (as of 10-27-2019), subject to change. Chris Bell: Candidate for Senate (Democratic Primary) Former Congressman Chris Bell is a native Texan, attorney, former US Congressman and Houston City Councilmember, husband, and father of two who is running for US Senate. Bell has decades of expe- rience in Texas Democratic politics, especially in Houston. He served on the City Council from 1997-2001, represented the area in the U.S. House from 2003-2005 and ran for governor in 2006. He was the Democratic nominee against then-Gov. Rick Perry, the Republican who won with 39% of the vote to Bell's 30%, while two independent candidates, Carole Keeton Strayhorn and Kinky Friedman, siphoned off the rest. Michael Cooper: Candidate for Senate (Democratic Primary) A former candidate for Lieutenant Govenor Michael Cooper is the President of the Beaumont NAACP. He earned a bachelor's degree in business and social studies from Lamar University Beaumont. Cooper's career experience includes working as a pastor at his local church, president of the South East Texas Toyota Dealers and in ex- ecutive management with Kinsel Motors. 936-250-1475 203 East Main, Suite 200, Nacogdoches, TX 75961 buildetx.org Hank Gilbert: Candidate for TX CD-1 (Democratic Primary) Hank Gilbert has lived in Congressional District 1 most of his life. A longtime rancher and successful small business owner, Hank spent many years watching our community be left behind. -

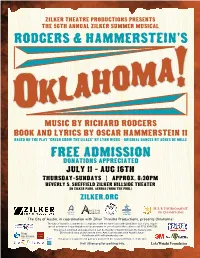

The City of Austin, in Coordination with Zilker Threatre Productions

The City of Austin, in coordination with Zilker Threatre Productions, presents Oklahoma! The City of Austin is committed to compliance with the Americans with Disabilities Act. If you require special assistance for participation in our programs or use of our facilities, please call (512) 974-6700. This project is funded and supported in part by the City of Austin through the Cultural Arts Division believing an investment in the Arts is an investment in Austin’s future. Visit Austin at NowPlayingAustin.com This project is supported in part by a grant from the Texas Commission on the Arts. Visit zilker.org for parking info. ZTP thanks our donors & in-kind contributors for their generous support! Zilker Theatre Productions proudly presents the 56th Annual Zilker Summer Musical Rodgers & Hammerstein’s Oklahoma! Music by RICHARD RODGERS Book and Lyrics by OSCAR HAMMERSTEIN II Based on the play “Green Grow the Lilacs” by Lynn Riggs Original Dances by Agnes de Mille CAST David Barnes · Connor Barr · Craig Barron · Ian J. Bethany · Madeline Boutwell · Matt Buzona Harrison Cardwell · Brittany Carson · Celeste Castillo · Zac Crofford · Tyler Michael Cullen · Brian Keith Davis Holly Gibson · Michelle Hache · Andie Haddad · Keith Hale · Leslie R. Hethcox · Sarah Howard J. Quinton Johnson · Aurora Lindsey · Lyrik Koottungal · Molly McCaskill · Devin Medley · Rose Mitchell Maranda Moody · Grace Morton · Sabrina Muir Stephen Muir · Karen Olson · Taylor Rainbolt Ann Richards · Danielle Ruth · Luke Sosebee · Dylan J. Tacker · Nicole Tate · Anna Vanston Chris Washington · Michael Wheeler · Kimberly Wilson DIRECTOR M. Scott Tatum CO-MUSIC DIRECTION DIRECTION AND CHOREOGRAPHY CO-MUSIC DIRECTION Molly Wissinger Courtney Wissinger James O. -

Morgan Independent School District (MISD)

TRANSMITTAL LETTER August 7, 2003 The Honorable Rick Perry, Governor The Honorable David Dewhurst, Lieutenant Governor The Honorable Thomas R. Craddick, Speaker of the House Chief Deputy Commissioner Robert Scott Fellow Texans: I am pleased to present my performance review of the Morgan Independent School District (MISD). This review is intended to help MISD hold the line on costs, streamline operations, and improve services to ensure that more of every education dollar goes directly into the classroom with the teachers and children, where it belongs. To aid in this task, I contracted with SoCo Consulting, Inc. I have made a number of recommendations to improve MISD's efficiency. I also have highlighted a number of "best practices" in district operations- model programs and services provided by the district's administrators, teachers, and staff. This report outlines 39 detailed recommendations that could save MISD $400,162 over the next five years, while reinvesting over $48,205 to improve educational services and other operations. Net savings are estimated to reach more than $351,957 that the district can redirect to the classroom. I am grateful for the cooperation of MISD's board, staff, parents, and community members. I commend them for their dedication to improving the educational opportunities for our most precious resource in MISD?the children. I am also pleased to announce that the report is available on my Window on State Government Web site at http://www.window.state.tx.us/tspr/morgan/. Sincerely, Carole Keeton Strayhorn Texas Comptroller c: Senate Committee on Education House Committee on Public Education The Honorable Kip Averitt, CPA, State Senator, District 22 The Honorable Arlene Wohlgemuth, State Representative, District 58 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY In March 2003, Texas Comptroller Carole Keeton Strayhorn began a review of the Morgan Independent School District (MISD). -

I T's the Weirdest Governor's Race in Modern Texas History. Three

t’s the weirdest governor’s race in modern Texas history. Three out of four funded candidates started their political careers as Democrats. Yet the one surviving Democrat has placed fourth Iin fundraising and struggles for the attention that all major-party nominees once received. Instead, some wealthy trial lawyers are backing an ex-Democrat who entered this race as a Republican—only to declare herself Independent shortly before the primary. This candidate—who soon will appear on the ballot under the third surname of her political career—recently lost her bid to be called “Grandma” on this ballot. Yet another Independent will appear on the ballot as “Kinky.” This country-western humorist was the race’s most entertaining candidate—at least until he tried to articulate a platform. His campaign-merchandising model has broken the campaign-finance mold. Yet it remains to be seen if people who advocate legalized pot or who buy Kinky paraphernalia will vote for anyone at all. Are people sporting “Why not Kinky?” bumper stickers themselves wrestling with this question? Finally the ex-Democrat now occupying the Governor’s Mansion leads the fundraising race—as expected of a big-business incumbent. By late June the governor already came close to matching the $25 million that George W. Bush raised by the end of his 1998 gubernatorial reelection campaign. Yet this governor enjoys none of the comfort with which his predecessor brushed off challenger Garry Mauro. This has less to do with this governor’s under-whelming track record than the fact that the victor in this wild, four-way race need not garner anywhere near 51 percent of the vote. -

Council Member Randi Shade's E-Mails From

Doherty, Deborah From: Shade, Randi Sent: Wednesday, January 19, 2011 10:34 PM To: Nathan, Mark Cc: Leffingwell, Lee; Martinez, Mike [Council Member] Subject: Re: New Time Proposed: Hold for working breakfast with AISD leadership Carstarphen talked about the role she wants city to play at tonight’s league of women . voters event. Laura was only other council member there. Wow -- it is quite an ask. look fwd to the discussion. Randi Shade 512—974—2255 (o) http://www.ci.austin.tx.us/council/shade.htm On Jan 19, 2011, at 5:17 PM, Nathan, Mark” <[email protected]> wrote: > > > > New Meeting Time Proposed: > Wednesday, January 26, 2011 8:00 AM-9:30 AM (GMT-06:00) Central Time (US & Canada) - > <meeting.ics> 1 Page 1 ot2 Doherty, Deborah From: Shade, Randi Sent: Wednesday, January 19, 2011 10:53AM To: ‘Sheryl Cole Cc: Long, Tara; Diaz, Elaine Subject: RE: 10 AM Friday Morning -- Emma Long Funeral Service No plans as of yet, but certainly something we can arrange. Depends on how many are going.... Randi Shade Austin City Council Council Member Place 3 (512) 974-2255 (phone) (512) 974-1888 (fax) From: Sheryl Cole Sent: Wednesday, January 19, 2011 10:52 AM To: Shade, Randi Cc: Long, Tara Subject: Re: 10 AM Friday Morning -- Emma Long Funeral Service Are we taking a van as a council? On Wed, Jan 19, 2011 at 10:19 AM, Shade, Randi <[email protected]> wrote: Dear Esteemed Fellow Female Austin City Council Members Past and Present -- I am writing to you today on behalf of Jeb Long, Emma’s son, to ask if you would be willing to sit together with the family during the funeral services scheduled for Emma Long this coming Friday morning. -

Undocumented Immigrants in Texas

HE COM T P F T O R O E L C L I E F R F O T EX A S Special Report December 2006 UNDOCUMENTED IMMIGRANTS IN TEXAS: A Financial Analysis of the Impact to the State Budget and Economy CAROLE KEETON STRAYHORN Texas Comptroller HE COM December 2006 T P F T O R O E L C L I E F R F O Special T E X A S Report CAROLE KEETON STRAYHORN • Texas Comptroller of Public Accounts UNDOCUMENTED IMMIGRANTS IN TEXAS: A Financial Analysis of the Impact to the State Budget and Economy “This is the first time any state has done a comprehensive financial analysis of the impact of undocumented immigrants on a state’s budget and economy, looking at gross state product, revenues generated, taxes paid and the cost of state services. “The absence of the estimated 1.4 million undocumented immigrants in Texas in fiscal 2005 would have been a loss to our gross state product of $17.7 billion. Undocumented immigrants produced $1.58 billion in state revenues, which exceeded the $1.16 billion in state services they received. However, local governments bore the burden of $1.44 billion in uncompensated health care costs and local law enforcement costs not paid for by the state.” — Carole Keeton Strayhorn, Texas Comptroller I. Introduction contrary to two recent reports, FAIR’s, “The Cost of Ille- gal Immigration to Texans” and the Bell Policy Center’s Much has been written in recent months about the costs “Costs of Federally Mandated Services to Undocumented and economic benefits associated with the rising number Immigrants in Colorado”, both of which identified costs of undocumented immigrants in Texas and the U.S. -

Orders of the Supreme Court of Texas Fiscal Year 2011 (September 1, 2010 – August 31, 2011)

Orders of the Supreme Court of Texas Fiscal Year 2011 (September 1, 2010 – August 31, 2011) Assembled by The Supreme Court of Texas Clerk’s Office Blake A. Hawthorne, Clerk of the Court Monica Zamarripa, Deputy Clerk THE SUPREME COURT OF TEXAS Orders Pronounced September 2, 2010 MISCELLANEOUS A STAY IS ISSUED IN THE FOLLOWING PETITION FOR WRIT OF MANDAMUS: 10-0599 IN RE CAMPBELL RANCH LLC, WILLIAM S. WALKER, WILLIAM L. DAWKINS, JR., ROBERT SCHULTE AND LEE HUBBARD; from Webb County; 4th district (04-10-00413-CV, ___ SW3d ___, 07-28-10) relators' motion for emergency stay granted in part real party in interest's motion for temporary relief denied stay order issued requested response due by 3:00 p.m., September 13, 2010 [Note: The petition for writ of mandamus remains pending before this Court.] THE SUPREME COURT OF TEXAS Orders Pronounced September 3, 2010 ORDERS ON CAUSES THE FOLLOWING CAUSE IS DISMISSED: 09-0270 XTO ENERGY INC. v. SMITH PRODUCTION INC.; from Harris County; 14th district (14-07-00069-CV, 282 SW3d 672, 02-24-09) unopposed motion to dismiss petition for review granted (Justice Guzman not sitting) THE MOTIONS IN THE FOLLOWING CAUSES ARE DENIED: 08-0961 MARIA DEL CARMEN GUILBOT SERROS DE GONZALEZ, ET AL. v. MIGUEL ANGEL GONZALEZ GUILBOT, CARLOS A. GONZALEZ GUILBOT, AND MARIA ROSA DEL ARENAL DE GONZALEZ; from Harris County; 14th district (14-07-00047-CV, 267 SW3d 556, 09-30-08) motion to stay mandate denied motion to recall mandate denied (Justice Guzman not sitting) 09-0191 HYDE PARK BAPTIST CHURCH v. -

Yff0e3 Veduete30 Off ALM A,L'a02

NOVEMBER 3, 2006 I $2.25 I OPENING THE EYES OF TEXAS FOR FIFTY ONE YEARS STATE PARK 114 E GOYS RNOR's MANSION THE EMINENT DOMAIN PE LAY'S s EASY MONEY BOTTOMLESS MEMORY PIT Avoid the pitfalls of the campaign trail and get your candidate to the Governor's Mansion first! l'a02 111,1118 19 1,197 Yff0E3 VEDUEtE30 Off ALM A, 0 NOVEMBER 3, 2006 TheTexas Observer Dialogue FEATURES GREAT WOMEN The Molly Ivins piece on Ann Richards vote I ever cast (and I have voted ["A-men. A-women. A-Ann," October WHY THE BELL NOT? 7 as Democratic ever since then for Can Chris Bell turn his serious mien into 6] was forwarded to me by a friend. all major elections, county, state and a campaign plus? THANK YOU VERY MUCH for a nationwide). Richards was simply by Jake Bernstein piece on a GREAT woman by another incredible. Ms. Ivins, I have seen you GREAT woman. speak in public, and you are one of IT ONLY HURTS WHEN HE LAUGHS 8 Cuthbert Thambimuttu, the best speakers and writers I have Kinky's bravado hides a dark vision Columbus, OH ever had the pleasure to hear and read. of politics and life Thank you so much! by Dave Mann Thank you for the story on Ann Jill A. Harper Richards. I loved her (from afar)! I am Denton County CAROLE THE CHAMELEON 10 still in mourning, but this helps lots. Four surnames and three party labels Roberta Hill THE CONTENDER later, will the real Carole Strayhorn Via e-mail Tim Eaton's piece on Juan Garcia please stand up? ["The Contender," September 22] was by Emily Pyle Thank you, Molly Ivins, for such first rate—and news to me out here in a wonderful, funny, and touching Sacramento. -

Hilltopics: Volume 3, Issue 9 Hilltopics Staff

Southern Methodist University SMU Scholar Hilltopics University Honors Program 11-6-2006 Hilltopics: Volume 3, Issue 9 Hilltopics Staff Follow this and additional works at: https://scholar.smu.edu/hilltopics Recommended Citation Hilltopics Staff, "Hilltopics: Volume 3, Issue 9" (2006). Hilltopics. 55. https://scholar.smu.edu/hilltopics/55 This document is brought to you for free and open access by the University Honors Program at SMU Scholar. It has been accepted for inclusion in Hilltopics by an authorized administrator of SMU Scholar. For more information, please visit http://digitalrepository.smu.edu. EXTENDED ELECTION SPECIAL volume three, issue nine www.smu.edu/honors/hilltopics week of november 06, 2006 ‘If we can keep it’: have we really earned our democracy? by Dr. Dayna Oscherwitz This election season, the AARP (As- at the decision to cast their vote for the Presi- sociation for the Advancement of Retired dent? Probably in the same way that many Persons) has been running a television ad Americans do. That is, they vote for a candi- entitled “Donʼt Vote.” The ad features an date because their friends, their family, their Endorsements: impeccably dressed pastor, a political par- Fellow Mus- politician who chops ty, or a television com- tangs endorse their favorite wood, drives a tractor, mercial tells them to, or candidates in the gover- and serves apple pie, they decide (rightly or nors race. Andrea Allen on but who categorically wrongly) that a candi- Carole Keeton Strayhorn and refuses to address any date agrees with them Samantha Urban on Chris serious political is- on a single issue, and Bell, page 3. -

Carole Keeton Strayhorn O

HE COM T P F T R Carole Keeton Strayhorn O O E L C L I Texas Comptroller of Public Accounts E F F R R O T E X A S 512/463-4000 512/463-4000 December 15, 2006 FAX: 512/463-4965 512/463-4965 P.O. BOX 13528 AUSTIN, TEXAS 78711-3528 The Honorable Rick Perry, Governor The Honorable David Dewhurst, Lieutenant Governor The Honorable Thomas R. Craddick, Speaker of the House Fellow Texans: In accordance with Article 4.73(a) of the Texas Insurance Code, I present herewith the first biennial report on the results of the implementation of a program establishing Premium Tax Credit for Investment in Certified Capital Companies (CAPCOs) for the period since program inception to January 1, 2006. This report provides information concerning the certification and investment activities of private venture capital companies formed to stimulate job creation and to increase the availability of growth capital for small busi- nesses located in the state. During 2005, ten Texas CAPCOs were certified to raise $200 million through the issuance of certified capital notes or “qualified debt instruments” to insurance companies. In return for their investments, 110 participating insurance companies will receive premium tax credits equal to 100 percent of the amount of their investments. This report includes the number, name, and amount of certified capital invested in each CAPCO; the amount each CAPCO has invested in qualified businesses as of January 1, 2006; the amount of tax credits granted for each year that credits have been granted; the renewal and reporting performance of each CAPCO; the size and industrial sector classification of qualified businesses receiving investment; the total number of jobs created and average wages paid for those jobs as a result of CAPCO investments; the total number of jobs retained and the average wages paid for those jobs as a result of CAPCO investments; and any CAPCOs that have been decerti- fied or failed to renew with the reason for any decertification.