Subscription Libraries, Literacy & Acculturation in the Colonies Of

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Some Notes on the Malayan Law of Negligence

Cleveland State Law Review Volume 9 Issue 3 Psychiatry and Law (A Symposium) Article 10 1960 Some Notes on the Malayan Law of Negligence A. E. S. Tay J. H. M. Heah Follow this and additional works at: https://engagedscholarship.csuohio.edu/clevstlrev Part of the Comparative and Foreign Law Commons, and the Torts Commons How does access to this work benefit ou?y Let us know! Recommended Citation A. E. S. Tay & J. H. M. Heah, Some Notes on the Malayan Law of Negligence, 9 Clev.-Marshall L. Rev. 490 (1960) This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Journals at EngagedScholarship@CSU. It has been accepted for inclusion in Cleveland State Law Review by an authorized editor of EngagedScholarship@CSU. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Some Notes on the Malayan Law of Negligence A. E. S. Tay* and J. H. M. Heah** T HE TERM "MALAYA" COVERS what are now two distinct political units: the fully independent Federation of Malaya and the semi-independent State of Singapore, which have emerged from a tangle of British settlements and colonies and British-protected Malay states. The State of Singapore has sprung from the Crown Colony of Singapore, which between 1826 and 1946 formed part of the larger Crown Colony of the Straits Settle- ments. The two remaining Straits settlements-Penang (includ- ing Province Wellesley) and Malacca-together with nine Malay states' have become the Federation of Malaya. Although Penang and Malacca, as British territories, have a very different legal history from that of the Malay states, their welding together into a political unit has been followed by legislation giving statu- tory foundation for the application of the English common law throughout the Federation; the historical differences, then, have lost their practical point. -

Program at a Glance

2019 International Congress of Odonatology Austin, Texas, USA 14–19 July 2019 ICO 2019 has been organized in conjunction with the Worldwide Dragonfly Association (WDA). ICO 2019 Book of Abstracts Editors: John C. Abbott and Will Kuhn Proofreading: Kendra Abbott and Manpreet Kohli Design and layout: John C. Abbott Congress logo design: Will Kuhn Printed in July 2019 Congress Logo The logo for ICO 2019 features the American Rubyspot, Hetaerina americana, a common species throughout the mainland United States. Both males and females of this damselfly species have brilliant metallic iridescent bodies, and males develop crimson patches on the basal fourth (or more) of their wings. You are sure to be greeted by the American Rubyspot along streams and rivers while you’re in Austin, as well as the Smoky Rubyspot (H. titia), which is also found in these parts. The logo also features the lone star of Texas. You’ll find that among the citizens of the US, Texans are exceptionally (and perhaps inordinately) proud of their state. The lone star is an element of the Texas state flag, which decorates many homes and businesses throughout the state. Once you start looking for it, you’ll never stop seeing it! 2 Table of Contents 2019 International Congress of Odonatology ..................................................................................................... 4 Venue, Accommodation & Registration ............................................................................................................... 5 About Austin ........................................................................................................................................................... -

Inscribed 6 (2).Pdf

Inscribed6 CONTENTS 1 1. AVIATION 33 2. MILITARY 59 3. NAVAL 67 4. ROYALTY, POLITICIANS, AND OTHER PUBLIC FIGURES 180 5. SCIENCE AND TECHNOLOGY 195 6. HIGH LATITUDES, INCLUDING THE POLES 206 7. MOUNTAINEERING 211 8. SPACE EXPLORATION 214 9. GENERAL TRAVEL SECTION 1. AVIATION including books from the libraries of Douglas Bader and “Laddie” Lucas. 1. [AITKEN (Group Captain Sir Max)]. LARIOS (Captain José, Duke of Lerma). Combat over Spain. Memoirs of a Nationalist Fighter Pilot 1936–1939. Portrait frontispiece, illustrations. First edition. 8vo., cloth, pictorial dust jacket. London, Neville Spearman. nd (1966). £80 A presentation copy, inscribed on the half title page ‘To Group Captain Sir Max AitkenDFC. DSO. Let us pray that the high ideals we fought for, with such fervent enthusiasm and sacrifice, may never be allowed to perish or be forgotten. With my warmest regards. Pepito Lerma. May 1968’. From the dust jacket: ‘“Combat over Spain” is one of the few first-hand accounts of the Spanish Civil War, and is the only one published in England to be written from the Nationalist point of view’. Lerma was a bomber and fighter pilot for the duration of the war, flying 278 missions. Aitken, the son of Lord Beaverbrook, joined the RAFVR in 1935, and flew Blenheims and Hurricanes, shooting down 14 enemy aircraft. Dust jacket just creased at the head and tail of the spine. A formidable Vic formation – Bader, Deere, Malan. 2. [BADER (Group Captain Douglas)]. DEERE (Group Captain Alan C.) DOWDING Air Chief Marshal, Lord), foreword. Nine Lives. Portrait frontispiece, illustrations. First edition. -

LAGOS CIVIL SOCIETY PARTNERSHIP for DEVELOPMENT 2021-2025 ABOUT the LACSOP STRATEGIC PLAN This Strategic Plan Sets the Direction for the Platform and the Secretariat

LAGOS CIVIL SOCIETY PARTNERSHIP FOR DEVELOPMENT 2021-2025 ABOUT THE LACSOP STRATEGIC PLAN This Strategic Plan sets the direction for the platform and the secretariat. Basically, this document presents who we are as an organisation, what we strive to achieve how we work and success definition. PHOTO CREDITS Dr UchenNa Uzo, Street selling (hawking) phenomeNoN in Nigeria The Guardian Newspaper, April 2018;Photos: Lagos FashioN Week, Vanguard, 27 October 2018; Dayo Adetiloye, FashioN School Business Plan in Nigeria; www.lolaakinmade.com; Apata OyediraN, Lagos Culture Carnival Kicks off Today, INdependent, December 2017; Nanacy Ruhling, Banana Island is billioNNair’s paradise, MasioN Global, 2 February 2019; Oladipo Abiola, NaijaNews, Lagos bus coNductors to get uNiforms as from 2018, 20 November 2017; Bukola Adebayo, NigeriaN state governors resolve to declare state of emergency oN rape following spate oN sexual violeNce, CNN, JuNe 12 2020; GTBank, Popular Markets in Nigeria, www.635.gtbank.com; Eko Festival AKA The Adimu Orisa Play, www.lagos-vacatioN.com/Eyo-Festival;The NatioNal Arts Theatre, www.allinNigeria.com,insights.invyo.io/africa/wpcoNteNt/uploads/2018/03; Techfoliance africa Nigeria fiNtech-hub regulatioN,www.cdN.autojosh.com/wpcoNteNt/uploads/2019/08/lag-past-9 TABLE OF CONTENT Message from Executive Secretary I Who are we 1 How we have contributed to Change in Lagos 3 Our Lagos, Our World 6 Our Theory of Change 8 Our Singular Goal 9 Lagos Civil Society for Development 10 Our Success Measures 12 Message from Executive Secretary I am ofteN introduced as a fouNder of LACSOP aNd it is differeNt a little differeNt to Now be iNtroduced as the Executive Secretary. -

Highland City Library: Long-Range Strategic Plan 2019-2022

Highland City Library: Long-range Strategic Plan 2019-2022 Introduction Public libraries have long been an important aspect of American life. From the early days of the Republic, libraries were valued by Americans. Benjamin Franklin founded the first subscription library in Philadelphia in 1732 with fifty members to make books more available for citizens of the young nation. From that time to the present, public libraries have been valued because they allow equal access to information and educational resources regardless of social or economic status. Library service has long been important to the residents of Highland. From 1994 to 2001, residents of Highland and Alpine were served by a joint use facility at Mountain Ridge Junior High School. That arrangement was eventually terminated and in 2001 the entire library collection was relocated to the old Highland City building for storage. In 2008, Highland City built a new city hall and dedicated a portion of the building for a city Library. In 2016 the Library received permission to convert a public meeting room into a Children’s Room for the Library. The new Children’s Room was opened in spring of 2018. The Library joined the North Utah County Library Cooperative (NUCLC) April 1, 2012 as an associate member. NUCLC is a reciprocal borrowing system that allows library card holders from participating libraries to check out materials from other participating libraries. It is not a county library system. Each participating library maintains its own policies, budget, administration, non-resident fees, etc. In 2018 the Library reached the required collection size and was accepted as a full NUCLC member. -

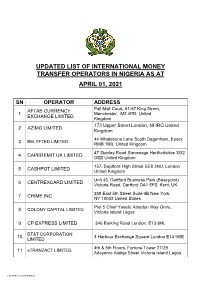

Updated List of International Money Transfer Operators in Nigeria As At

UPDATED LIST OF INTERNATIONAL MONEY TRANSFER OPERATORS IN NIGERIA AS AT APRIL 01, 2021 SN OPERATOR ADDRESS AFTAB CURRENCY Pall Mall Court, 61-67 King Street, 1 Manchester, M2 4PD, United EXCHANGE LIMITED Kingdom 173 Upper Street London, NI IRG United 2 AZIMO LIMITED Kingdom 44 Whalebone Lane South Dagenham, Essex 3 BELYFTED LIMITED RMB 1BB, United Kingdom 47 Stanley Road Stevenage Hertfordshire SG2 4 CAPEREMIT UK LIMITED OEE United Kingdom 157, Deptford High Street SE8 3NU, London 5 CASHPOT LIMITED United Kingdom Unit 46, Dartford Business Park (Basepoint) 6 CENTREXCARD LIMITED Victoria Road, Dartford DA1 5FS, Kent, UK 239 East 5th Street Suite 4B New York, 7 CHIME INC. NY 10003 United States Plot 5 Chief Yesefu Abiodun Way Oniru, 8 COLONY CAPITAL LIMITED Victoria Island Lagos 9 CP EXPRESS LIMITED 346 Barking Road London, E13 8HL DT&T CORPORATION 10 3 Harbour Exchange Square London E14 9GE LIMITED 4th & 5th Floors, Fortune Tower 27/29 11 eTRANZACT LIMITED Adeyemo Alakija Street Victoria Island Lagos Classified as Confidential FIEM GROUP LLC DBA 1327, Empire Central Drive St. 110-6 Dallas 12 PING EXPRESS Texas 6492 Landover Road Suite A1 Landover 13 FIRST APPLE INC. MD20785 Cheverly, USA FLUTTERWAVE 14 TECHNOLOGY SOLUTIONS 8 Providence Street, Lekki Phase 1 Lagos LIMITED FORTIFIED FRONTS LIMITED 15 in Partnership with e-2-e PAY #15 Glover Road Ikoyi, Lagos LIMITED FUNDS & ELECTRONIC 16 No. 15, Cameron Road, Ikoyi, Lagos TRANSFER SOLUTION FUNTECH GLOBAL Clarendon House 125 Shenley Road 17 COMMUNICATIONS Borehamwood Heartshire WD6 1AG United LIMITED Kingdom GLOBAL CURRENCY 1280 Ashton Old Road Manchester, M11 1JJ 18 TRAVEL & TOURS LIMITED United Kingdom Rue des Colonies 56, 6th Floor-B1000 Brussels 19 HOMESEND S.C.R.L Belgium IDT PAYMENT SERVICES 20 520 Broad Street USA INC. -

CHEMISTRY International October-December 2019 Volume 41 No

CHEMISTRY International The News Magazine of IUPAC October-December 2019 Volume 41 No. 4 Special IYPT2019 Elements of X INTERNATIONAL UNION OFBrought to you by | IUPAC The International Union of Pure and Applied Chemistry PURE AND APPLIED CHEMISTRY Authenticated Download Date | 11/6/19 3:09 PM Elements of IYPT2019 CHEMISTRY International he Periodic Table of Chemical Elements has without any The News Magazine of the doubt developed to one of the most significant achievements International Union of Pure and Tin natural sciences. The Table (or System, as called in some Applied Chemistry (IUPAC) languages) is capturing the essence, not only of chemistry, but also of other science areas, like physics, geology, astronomy and biology. All information regarding notes for contributors, The Periodic Table is to be seen as a very special and unique tool, subscriptions, Open Access, back volumes and which allows chemists and other scientists to predict the appear- orders is available online at www.degruyter.com/ci ance and properties of matter on earth and even in other parts of our the universe. Managing Editor: Fabienne Meyers March 1, 1869 is considered as the date of the discovery of the Periodic IUPAC, c/o Department of Chemistry Law. That day Dmitry Mendeleev completed his work on “The experi- Boston University ence of a system of elements based on their atomic weight and chemi- Metcalf Center for Science and Engineering cal similarity.” This event was preceded by a huge body of work by a 590 Commonwealth Ave. number of outstanding chemists across the world. We have elaborated Boston, MA 02215, USA on that in the January 2019 issue of Chemistry International (https:// E-mail: [email protected] bit.ly/2lHKzS5). -

Tan Sierra Research 1

Running Head: Sierra Tan’s Research Paper #1 1 Education in India With a population of more than 1.2 billion, India has the second largest education system in the world (after China). According to a 2011 Census conducted by the United Nations Population Division, half of its population is under the age of 25, depicting an image of a youthful engine for economic growth. However, this growth can only be achieved if the many problems in its education system can be resolved. For example, India is one of the countries with a high illiteracy rate with a quarter of its population un-educated; there is a large gap between male and female literacy rate; and the teaching quality is very low, especially in public sectors. This research paper aims to help our readers understand education in India, and identify what factors have contributed to its current status. I will start with an overview of India’s education system and its major characteristics; then I will explore the causal factors from cultural, historical, and philosophical perspectives respectively; and conclude with some recommendations for its future development. Overview of India’s Education System Structure India is divided into 29 states and 7 “Union Territories”. Education in India is provided by the public as well as the private sector, with control and funding coming from three levels – central, state, and local, and it falls under the control of both the Union Government and the states, with some responsibilities lying with the Union and the states having autonomy for others. The apex body for curriculum related matters for school education in India is the National Council of Educational Research and Training (NCERT), which plays a central role in developing policies and programs. -

Nigerian Nationalism: a Case Study in Southern Nigeria, 1885-1939

Portland State University PDXScholar Dissertations and Theses Dissertations and Theses 1972 Nigerian nationalism: a case study in southern Nigeria, 1885-1939 Bassey Edet Ekong Portland State University Follow this and additional works at: https://pdxscholar.library.pdx.edu/open_access_etds Part of the African Studies Commons, and the International Relations Commons Let us know how access to this document benefits ou.y Recommended Citation Ekong, Bassey Edet, "Nigerian nationalism: a case study in southern Nigeria, 1885-1939" (1972). Dissertations and Theses. Paper 956. https://doi.org/10.15760/etd.956 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access. It has been accepted for inclusion in Dissertations and Theses by an authorized administrator of PDXScholar. Please contact us if we can make this document more accessible: [email protected]. AN ABSTRACT OF' THE 'I'HESIS OF Bassey Edet Skc1::lg for the Master of Arts in History prt:;~'entE!o. 'May l8~ 1972. Title: Nigerian Nationalism: A Case Study In Southern Nigeria 1885-1939. APPROVED BY MEMBERS OF THE THESIS COMMITIIEE: ranklln G. West Modern Nigeria is a creation of the Britiahl who be cause of economio interest, ignored the existing political, racial, historical, religious and language differences. Tbe task of developing a concept of nationalism from among suoh diverse elements who inhabit Nigeria and speak about 280 tribal languages was immense if not impossible. The tra.ditionalists did their best in opposing the Brltlsh who took away their privileges and traditional rl;hts, but tbeir policy did not countenance nationalism. The rise and growth of nationalism wa3 only po~ sible tbrough educs,ted Africans. -

Michigan Libraries

Michigan Time Traveler Michigan Time Traveler An educational supplement produced by Lansing Newspapers In Education, Inc. and the Michigan Historical Center. Read This Summer! Until the 20th century, children under the age of 10 were not allowed to use most libraries. Other than nursery rhymes, there weren’t many books for kids. Today that has changed! Libraries have neat areas for kids with books, activities, even computers! Every summer millions of kids read for fun. By joining a summer reading program at their local library, they get free stuff and win prizes. Jim — “the Spoon Man” KIDS’KIDS’ — Cruise (photo, center) says reading is like exercising, “Whenever you read a book, I call it ‘lifting weights for your brain.’” This year many Michigan libraries are celebrating “Laugh It Up @ History Your Library.” These libraries History have lots of books good for laughing, learning and just loafing this summer. The Spoon aries Man had everybody laughing at Time Lansing’s Libraries the Capital Area District higan Libr s Lansing’s first library was a subscription library. Library Summer Reading Mic This month’ During the 1860s, the Ladies’ Library and Program kickoff. After One of the best ways to be a Literary Association started a library on West the program Traveler is to read a book. Michigan Avenue for its members. It cost $2 to Marcus and me Traveler explores the history of belong, and the library was open only on Lindsey (above left) Ti Saturdays. Then, in 1871, the Lansing Board of joined him to look places filled with books — libraries. -

Language Planning and the British Empire: Comparing Pakistan, Malaysia and Kenya

Current Issues in Language Planning ISSN: 1466-4208 (Print) 1747-7506 (Online) Journal homepage: http://www.tandfonline.com/loi/rclp20 Language Planning and the British Empire: Comparing Pakistan, Malaysia and Kenya Richard Powell To cite this article: Richard Powell (2002) Language Planning and the British Empire: Comparing Pakistan, Malaysia and Kenya, Current Issues in Language Planning, 3:3, 205-279, DOI: 10.1080/14664200208668041 To link to this article: http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/14664200208668041 Published online: 26 Mar 2010. Submit your article to this journal Article views: 305 View related articles Citing articles: 6 View citing articles Full Terms & Conditions of access and use can be found at http://www.tandfonline.com/action/journalInformation?journalCode=rclp20 Download by: [University of Pennsylvania] Date: 02 December 2015, At: 15:06 Language Planning and the British Empire: Comparing Pakistan, Malaysia and Kenya1 Richard Powell College of Economics, Nihon University, Misaki-cho 1-3-2, Chiyoda-ku, Tokyo 101-8360 Japan Thispaper seeks to provide historicalcontext for discussions of languageplanning in postcolonialsocieties by focusing on policieswhich haveinfluenced language in three formerBritish colonies. If wemeasure between the convenient markers of John Cabot’s Newfoundland expeditionof 1497and the1997 return of Hong Kong toChinesesover- eignty,the British Empire spanned 500years, 2 and atitsgreatest extent in the1920s covereda fifthof theworld’ s landsurface. Together with the economic and military emergenceof theUnited -

Country Coding Units

INSTITUTE Country Coding Units v11.1 - March 2021 Copyright © University of Gothenburg, V-Dem Institute All rights reserved Suggested citation: Coppedge, Michael, John Gerring, Carl Henrik Knutsen, Staffan I. Lindberg, Jan Teorell, and Lisa Gastaldi. 2021. ”V-Dem Country Coding Units v11.1” Varieties of Democracy (V-Dem) Project. Funders: We are very grateful for our funders’ support over the years, which has made this ven- ture possible. To learn more about our funders, please visit: https://www.v-dem.net/en/about/ funders/ For questions: [email protected] 1 Contents Suggested citation: . .1 1 Notes 7 1.1 ”Country” . .7 2 Africa 9 2.1 Central Africa . .9 2.1.1 Cameroon (108) . .9 2.1.2 Central African Republic (71) . .9 2.1.3 Chad (109) . .9 2.1.4 Democratic Republic of the Congo (111) . .9 2.1.5 Equatorial Guinea (160) . .9 2.1.6 Gabon (116) . .9 2.1.7 Republic of the Congo (112) . 10 2.1.8 Sao Tome and Principe (196) . 10 2.2 East/Horn of Africa . 10 2.2.1 Burundi (69) . 10 2.2.2 Comoros (153) . 10 2.2.3 Djibouti (113) . 10 2.2.4 Eritrea (115) . 10 2.2.5 Ethiopia (38) . 10 2.2.6 Kenya (40) . 11 2.2.7 Malawi (87) . 11 2.2.8 Mauritius (180) . 11 2.2.9 Rwanda (129) . 11 2.2.10 Seychelles (199) . 11 2.2.11 Somalia (130) . 11 2.2.12 Somaliland (139) . 11 2.2.13 South Sudan (32) . 11 2.2.14 Sudan (33) .