Anti-Predator Defence Drives Parallel Morphological Evolution in Flea

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Entomologische Arbeiten Aus Dem Museum G. Frey Tutzing Bei München

ZOBODAT - www.zobodat.at Zoologisch-Botanische Datenbank/Zoological-Botanical Database Digitale Literatur/Digital Literature Zeitschrift/Journal: Entomologische Arbeiten Museum G. Frey Jahr/Year: 1983 Band/Volume: 31-32 Autor(en)/Author(s): Virkki Niilo, Zambrana Iraida Artikel/Article: Life history of Alagoasa bicolor (L.) in indoor rearing conditions (Coleoptera - Chrysomelidae - Alticinae). 131-155 download Biodiversity Heritage Library, http://www.biodiversitylibrary.org/ Ent. Arb. Mus. Frey 31/32, 1983 131 Life history of Alagoasa bicolor (L.) in indoor rearing condi- 1 tions ) (Coleoptera - Chrysomelidae - Alticinae) By Niilo Virkki and Iraida Zambrana Puerto Rico Abstract Alagoasa bicolor (L.) (Alticinae) was successfully reared on its hostplant in outdoor and indoor conditions. Mating, and development from eggs to adults was followed in petri dish cultures. Timing of the stages in these conditions was approximately as follows: Eggs 10 days Larva I 8 days Larva II 7 days Larva III 11 days Prepupa 2 days Pupa 10 days Subterranean adult 2 days TOTAL 50 days The female oviposits on the soil. Larvae spend most of their time in lethargic aggregations on the soil. The pigmentation of prothoracic and anal shields of the larvae serves as a criterion of the instar: in the first instar they are black, in the second, gray, and in the third, they approximate the general body color. A prominent exuvium of oesophageal chitine is drawn out at the larval moltings. This might be a genus specialty, because in Omophoita, an anal exuvium was seen to be more prominent. Introduction Blake (1927) preliminarily published Boving and Craighead's (1931) Illustration of a larva of Omophoita gibbitarsa Say, providing at the same time data on host plants, ovipo- sition, and pupation. -

T1)E Bedford,1)Ire Naturaii,T 45

T1)e Bedford,1)ire NaturaIi,t 45 Journal for the year 1990 Bedfordshire Natural History Society 1991 'ISSN 0951 8959 I BEDFORDSHffiE NATURAL HISTORY SOCIETY 1991 Chairman: Mr D. Anderson, 88 Eastmoor Park, Harpenden, Herts ALS 1BP Honorary Secretary: Mr M.C. Williams, 2 Ive! Close, Barton-le-Clay, Bedford MK4S 4NT Honorary Treasurer: MrJ.D. Burchmore, 91 Sundon Road, Harlington, Dunstable, Beds LUS 6LW Honorary Editor (Bedfordshire Naturalist): Mr C.R. Boon, 7 Duck End Lane, Maulden, Bedford MK4S 2DL Honorary Membership Secretary: Mrs M.]. Sheridan, 28 Chestnut Hill, Linslade, Leighton Buzzard, Beds LU7 7TR Honorary Scientific Committee Secretary: Miss R.A. Brind, 46 Mallard Hill, Bedford MK41 7QS Council (in addition to the above): Dr A. Aldhous MrS. Cham DrP. Hyman DrD. Allen MsJ. Childs Dr P. Madgett MrC. Baker Mr W. Drayton MrP. Soper Honorary Editor (Muntjac): Ms C. Aldridge, 9 Cowper Court, Markyate, Herts AL3 8HR Committees appointed by Council: Finance: Mr]. Burchmore (Sec.), MrD. Anderson, Miss R. Brind, Mrs M. Sheridan, Mr P. Wilkinson, Mr M. Williams. Scientific: Miss R. Brind (Sec.), Mr C. Boon, Dr G. Bellamy, Mr S. Cham, Miss A. Day, DrP. Hyman, MrJ. Knowles, MrD. Kramer, DrB. Nau, MrE. Newman, Mr A. Outen, MrP. Trodd. Development: Mrs A. Adams (Sec.), MrJ. Adams (Chairman), Ms C. Aldridge (Deputy Chairman), Mrs B. Chandler, Mr M. Chandler, Ms]. Childs, Mr A. Dickens, MrsJ. Dickens, Mr P. Soper. Programme: MrJ. Adams, Mr C. Baker, MrD. Green, MrD. Rands, Mrs M. Sheridan. Trustees (appointed under Rule 13): Mr M. Chandler, Mr D. Green, Mrs B. -

210 – Lanuza-Garay A., Chiru L., Lopez Chon O

ISSN 1021-0296 REVISTA NICARAGUENSE DE ENTOMOLOGIA N° 210 Septiembre 2020 NEW COUNTRY RECORDS OF LEAF AND LONGHORN BEETLES (COLEOPTERA: CHRYSOMELOIDEA) COLLECTED IN THE TROGON TRAIL, PROVINCE OF COLON, PANAMA. ALFREDO LANUZA-GARAY, LERIDA CHIRÚ, OSCAR LÓPEZ CHONG & ALONSO SANTOS-MURGAS PUBLICACIÓN DEL MUSEO ENTOMOLÓGICO ASOCIACIÓN NICARAGÜENSE DE ENTOMOLOGÍA LEÓN - - - NICARAGUA Revista Nicaragüense de Entomología. Número 210. 2020. La Revista Nicaragüense de Entomología (ISSN 1021-0296) es una publicación reconocida en la Red de Revistas Científicas de América Latina y el Caribe, España y Portugal (Red ALyC). Todos los artículos que en ella se publican son sometidos a un sistema de doble arbitraje por especialistas en el tema. The Revista Nicaragüense de Entomología (ISSN 1021-0296) is a journal listed in the Latin-American Index of Scientific Journals. Two independent specialists referee all published papers. Consejo Editorial Jean Michel Maes Fernando Hernández-Baz Editor General Editor Asociado Museo Entomológico Universidad Veracruzana Nicaragua México José Clavijo Albertos Silvia A. Mazzucconi Universidad Central de Universidad de Buenos Aires Venezuela Argentina Weston Opitz Don Windsor Kansas Wesleyan University Smithsonian Tropical Research United States of America Institute, Panama Fernando Fernández Jack Schuster Universidad Nacional de Universidad del Valle de Colombia Guatemala Julieta Ledezma Olaf Hermann Hendrik Museo de Historia Natural Mielke “Noel Kempf” Universidade Federal do Bolivia Paraná, Brasil _______________ Foto de la portada: Platyphora haroldi Baly, 1877. Panamá, Provincia de Colón, Achiote. 7 septiembre 2017 (foto Alonso Santos-Murgas). Página 2 Revista Nicaragüense de Entomología. Número 210. 2020. NEW COUNTRY RECORDS OF LEAF AND LONGHORN BEETLES (COLEOPTERA: CHRYSOMELOIDEA) COLLECTED IN THE TROGON TRAIL, PROVINCE OF COLON, PANAMA. -

Barcoding Chrysomelidae: a Resource for Taxonomy and Biodiversity Conservation in the Mediterranean Region

A peer-reviewed open-access journal ZooKeys 597:Barcoding 27–38 (2016) Chrysomelidae: a resource for taxonomy and biodiversity conservation... 27 doi: 10.3897/zookeys.597.7241 RESEARCH ARTICLE http://zookeys.pensoft.net Launched to accelerate biodiversity research Barcoding Chrysomelidae: a resource for taxonomy and biodiversity conservation in the Mediterranean Region Giulia Magoga1,*, Davide Sassi2, Mauro Daccordi3, Carlo Leonardi4, Mostafa Mirzaei5, Renato Regalin6, Giuseppe Lozzia7, Matteo Montagna7,* 1 Via Ronche di Sopra 21, 31046 Oderzo, Italy 2 Centro di Entomologia Alpina–Università degli Studi di Milano, Via Celoria 2, 20133 Milano, Italy 3 Museo Civico di Storia Naturale di Verona, lungadige Porta Vittoria 9, 37129 Verona, Italy 4 Museo di Storia Naturale di Milano, Corso Venezia 55, 20121 Milano, Italy 5 Department of Plant Protection, College of Agriculture and Natural Resources–University of Tehran, Karaj, Iran 6 Dipartimento di Scienze per gli Alimenti, la Nutrizione e l’Ambiente–Università degli Studi di Milano, Via Celoria 2, 20133 Milano, Italy 7 Dipartimento di Scienze Agrarie e Ambientali–Università degli Studi di Milano, Via Celoria 2, 20133 Milano, Italy Corresponding authors: Matteo Montagna ([email protected]) Academic editor: J. Santiago-Blay | Received 20 November 2015 | Accepted 30 January 2016 | Published 9 June 2016 http://zoobank.org/4D7CCA18-26C4-47B0-9239-42C5F75E5F42 Citation: Magoga G, Sassi D, Daccordi M, Leonardi C, Mirzaei M, Regalin R, Lozzia G, Montagna M (2016) Barcoding Chrysomelidae: a resource for taxonomy and biodiversity conservation in the Mediterranean Region. In: Jolivet P, Santiago-Blay J, Schmitt M (Eds) Research on Chrysomelidae 6. ZooKeys 597: 27–38. doi: 10.3897/ zookeys.597.7241 Abstract The Mediterranean Region is one of the world’s biodiversity hot-spots, which is also characterized by high level of endemism. -

Toxicology in Antiquity

TOXICOLOGY IN ANTIQUITY Other published books in the History of Toxicology and Environmental Health series Wexler, History of Toxicology and Environmental Health: Toxicology in Antiquity, Volume I, May 2014, 978-0-12-800045-8 Wexler, History of Toxicology and Environmental Health: Toxicology in Antiquity, Volume II, September 2014, 978-0-12-801506-3 Wexler, Toxicology in the Middle Ages and Renaissance, March 2017, 978-0-12-809554-6 Bobst, History of Risk Assessment in Toxicology, October 2017, 978-0-12-809532-4 Balls, et al., The History of Alternative Test Methods in Toxicology, October 2018, 978-0-12-813697-3 TOXICOLOGY IN ANTIQUITY SECOND EDITION Edited by PHILIP WEXLER Retired, National Library of Medicine’s (NLM) Toxicology and Environmental Health Information Program, Bethesda, MD, USA Academic Press is an imprint of Elsevier 125 London Wall, London EC2Y 5AS, United Kingdom 525 B Street, Suite 1650, San Diego, CA 92101, United States 50 Hampshire Street, 5th Floor, Cambridge, MA 02139, United States The Boulevard, Langford Lane, Kidlington, Oxford OX5 1GB, United Kingdom Copyright r 2019 Elsevier Inc. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, or any information storage and retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publisher. Details on how to seek permission, further information about the Publisher’s permissions policies and our arrangements with organizations such as the Copyright Clearance Center and the Copyright Licensing Agency, can be found at our website: www.elsevier.com/permissions. This book and the individual contributions contained in it are protected under copyright by the Publisher (other than as may be noted herein). -

Insects for Weed Control: Status in North Dakota

Insects for Weed Control: Status in North Dakota E. U. Balsbaugh, Jr. Associate Professor, Department of Entomology R. D. Frye Professor, Department of Entomology C. G. Scholl Plant Protection Specialist, North Dakota State Department of Agriculture A. W. Anderson Associate Professor, Department of Entomology Two foreign species of weevils have been introduced into North Dakota for the biological control of musk thistle, Carduus nutans L. - Rhinocyllus conicus (Froelich), a seed feeding weevH, and Ceutorrhynchidius horridus (Panzer), an internal root and lower stem inhabiting species. R. conicus has survived for several generations and is showing some promise for thistle suppression in Walsh County, but releases of C. hor ridus have been unsuccessful. The pigweed nea beetle, Disonycha glabrata (Fab.), which is native in southern United States, has been introduced into experimental sugarbeet plots in the Red River Valley for testing its effects at controlling rough pigweed or redroot, Amaranthus retroflexus L. Although both larvae and adults of these beetles feed heavily on pigweed, damage to the weed occurs too late in the season for them to be effective in suppressing weed growth or seed set. An initial survey for native insects of bindweed has been conducted. Feeding by localized populations of various insects, particularly tortoise beetles, has been observed. Several foreign species of nea beetles and a stem boring beetle are anticipated for release against leafy spurge. Entomologists at North Dakota State University are successful. In 1940, the cactus-feeding moth, Cac studying insects that feed on weeds to determine if the toblastis cactorum (Berg), was transported from its insects can reduce populations of selected weeds to native Argentina to Australia where it greatly reduced levels at which the weeds no longer are economically im the numbers of prickly pear cactus, Opuntia spp. -

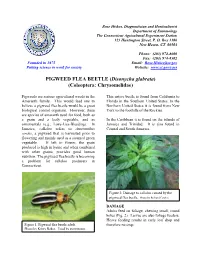

PIGWEED FLEA BEETLE (Disonycha Glabrata) (Coleoptera: Chrysomelidae)

Rose Hiskes, Diagnostician and Horticulturist Department of Entomology The Connecticut Agricultural Experiment Station 123 Huntington Street, P. O. Box 1106 New Haven, CT 06504 Phone: (203) 974-8600 Fax: (203) 974-8502 Founded in 1875 Email: [email protected] Putting science to work for society Website: www.ct.gov/caes PIGWEED FLEA BEETLE (Disonycha glabrata) (Coleoptera: Chrysomelidae) Pigweeds are serious agricultural weeds in the This native beetle is found from California to Amaranth family. This would lead one to Florida in the Southern United States. In the believe a pigweed flea beetle would be a great Northern United States it is found from New biological control organism. However, there York to the foothills of the Rockies. are species of amaranth used for food, both as a grain and a leafy vegetable, and as In the Caribbean it is found on the islands of ornamentals (e.g., Love-Lies-Bleeding). In Jamaica and Trinidad. It is also found in Jamaica, callaloo refers to Amaranthus Central and South America. viridis, a pigweed that is harvested prior to flowering and mainly used as a steamed green vegetable. If left to flower, the grain produced is high in lysine and when combined with other grains, provides good human nutrition. The pigweed flea beetle is becoming a problem for callaloo producers in Connecticut. Figure 2. Damage to callaloo caused by the pigweed flea beetle. Photo by Richard Cowles. DAMAGE Adults feed on foliage, chewing small, round holes (Fig. 2). Larvae are also foliage feeders. Heavy feeding results in early leaf drop and Figure 1. -

SPIXIANA ©Zoologische Staatssammlung München;Download

©Zoologische Staatssammlung München;download: http://www.biodiversitylibrary.org/; www.biologiezentrum.at SPIXIANA ©Zoologische Staatssammlung München;download: http://www.biodiversitylibrary.org/; www.biologiezentrum.at at leaping (haitikos in Greek) for locomotion and escape; thus, the original valid name of the type genus Altica Müller, 1764 (see Fürth, 1981). Many Flea Beetles are among the most affective jumpers in the animal kingdom, sometimes better than their namesakes the true Fleas (Siphonaptera). However, despite some intensive study of the anatomy and function of the metafemoral spring (Barth, 1954; Ker, 1977) the true function of this jumping mechanism remains a mystery. It probably is some sort of voluntary Catch, in- volving build-up of tension from the large muscles that insert on the metafemoral spring (Fig. 1), and theo a quick release of this energy. Ofcourse some Flea Beetles jump better than others, but basically all have this internal metafemoral spring floating by attachment from large muscles in the relatively enlarged bind femoral capsule (see Fig. 1 ). In fact Flea Beetles can usually be easily separated from other beetles, including chrysomelid subfa- milies, by their greatly swollen bind femora. There are a few genera of Alticinae that have a metafemoral spring and yet do not jump. Actually there are a few genera that are considered to be Alticinae that lack the metafemo- ral spring, e. g. Orthaltica (Scherer, 1974, 1981b - as discussed in this Symposium). Also the tribe Decarthrocerini contains three genera from Africa that Wilcox (1965) con- sidered as Galerucinae, but now thinks to be intermediate between Galerucinae and Alti- cinae; at least one of these genera does have a metafemoral spring (Wilcox, personal communication, and Fürth, unpublished data). -

SPECIES of PHYTOPHAGOUS INSECTS ASSOCIATED with STRAWBERRIES in LATVIA Valentîna Petrova, Lîga Jankevica, and Ineta Samsone

PROCEEDINGS OF THE LATVIAN ACADEMY OF SCIENCES. Section B, Vol. 67 (2013), No. 2 (683), pp. 124–129. DOI: 10.2478/prolas-2013-0019 SPECIES OF PHYTOPHAGOUS INSECTS ASSOCIATED WITH STRAWBERRIES IN LATVIA Valentîna Petrova, Lîga Jankevica, and Ineta Samsone Institute of Biology, University of Latvia, Miera ielâ 3, Salaspils, LV-2169, LATVIA [email protected] Communicated by Viesturs Melecis The aim of the present study was to describe the phytophagous insect fauna of strawberries in Latvia. This study was carried out in 2000–2004 on strawberry plantations in Tukums, Rîga, Do- bele, and Limbaþi districts. Insects were collected from strawberry fields by pitfall trapping, sweep netting and leaf sampling methods. A total of 137 insect species belonging to seven orders and 41 families were identified to species. Of the phytophagous insects, the order Orthoptera was represented by one species, other orders by a larger number of species: Hymenoptera (3), Dip- tera (16), Lepidoptera (20), Thysanoptera (21), Hemiptera (39), and Coleoptera (37). Of the re- corded insects, 48 species have a status of general strawberry pests. Key words: Fragaria × ananassa, strawberry pests, insect diversity. INTRODUCTION planted in rows with 30-cm distance between plants and 100-cm distance between rows. In the period from June 1 to Strawberries are one of the commercially important crop September 30 in 2000–2004, random sweep netting plants in Latvia. Harmful phytophagous insect species on (monthly) and leaf sampling (twice a month) were performed strawberry have been studied during the period between for general collection of homopterans, thysanopterans, 1928 and 1989. Thirty-four phytophagous insect species lepidopterans and hemipterans. -

Synchronous Coadaptation in an Ancient Case of Herbivory

Synchronous coadaptation in an ancient case of herbivory Judith X. Becerra* Department of Entomology, University of Arizona, Tucson, AZ 85721 Edited by William S. Bowers, University of Arizona, Tucson, AZ, and approved August 28, 2003 (received for review May 19, 2003) Coevolution has long been considered a major force leading to the one of the main Blepharida hosts is Commiphora. Diamphidia adaptive radiation and diversification of insects and plants. A from Africa and Podontia from Asia are also very closely related fundamental aspect of coevolution is that adaptations and coun- to Blepharida (14, 16). Diamphidia, the renowned poison-arrow teradaptations interlace in time. A discordant origin of traits long beetle of the !Kung San of South Central Africa, also feeds on before or after the origin of the putative coevolutionary selective Commiphora (16, 17). The hosts of Podontia are not well known, pressure must be attributed to other evolutionary processes. De- although a few species have been found on the Anacardiaceae spite the importance of this distinction to our understanding of genus Rhus (13). Because Blepharida feeds on members of the coevolution, the macroevolutionary tempo of innovation in plant same plant family in both the New and Old World tropics, it has defenses and insect counterdefenses has not been documented. been suggested that the interaction probably started before the Molecular clocks for a lineage of chrysomelid beetles of the genus separation of Africa and South America (15, 18). Blepharida and their Burseraceae hosts were independently cali- Some Bursera and Blepharida species exhibit remarkable brated. Results show that these plants’ defenses and the insect’s defensive and counterdefensive mechanisms that have been counterdefensive feeding traits evolved roughly in synchrony, attributed to their coevolution (19, 20). -

Note Faunistiche, Tassonomiche Ed Ecologiche Su Alcune Specie Di Chrysomelidae Alticinae Della Penisola Iberica (Col.) *

NOTE FAUNISTICHE, TASSONOMICHE ED ECOLOGICHE SU ALCUNE SPECIE DI CHRYSOMELIDAE ALTICINAE DELLA PENISOLA IBERICA (COL.) * M. Biondi ** RIASSUNTO Nel presente lavoro sono riportate alcune osservazioni faunistiche, tassonomiche ed eco- logiche su 106 specie di Chrysomelidae Alticinae presenti nella Penisola Iberica. Crepido- dera aureola (Foudras) e Longitarsus danieli Mohr vengono qui considerate come specie va- lide. Asiorestia femorata (Gyllenhal), Longitarsus gracilis Kutschera. L. leonardii Doguet. L. salviae Gruev, Phyllotreta balcanica Heikertinger, risultano nuove per la fauna iberica, e Phyllotreta cruralis Abeille de Perrin risulta nuova anche per la fauna europea. Viene inol- tre confermata la presenza in Spagna di Batophila pyrenaea Allard, Derocrepis rufipes (Lin- naeus) e Longitarsus holsaticus (Linnaeus). Parole chiave: Coleoptera, Chrysomelidae, Alticinae, tassonomia, ecologia, Penisola lberica. ABSTRACT Faunistic, taxonomic and ecological notes on some species of Chrysomelidae Alticinae from the Iberian Peninsula (Col.). New faunistic data and taxonomic observations on 106 species of flea beetles from Spain are reported. Crepidodera aureola (Foudras) and Longitarsus danieli Mohr are considered good species. Asiorestia femorata (Gyllenhal), Longitarsus gracilis Kutschera, L. leonardii Doguet. L. salviae Gruev and Phyllotreta balcanica Heikertinger are new for the Iberian fauna, and Phyllotreta cruralis Abeille de Perrin is new also for the European fauna. Mo- reover the presence in Spain of Batophila pyrenaea Allard, Derocrepis -

Onetouch 4.0 Scanned Documents

IL Volume 3 1985 pp. 375-392 FIRST INTERNATIONALSYMPOSIUM ON THE CHRYSOMEIADAE Held in Conjunction with The XVII International Congress of Entomology, Hamburg August 20-25,1984 Relationships of Palearctic and Nearctic Genera of Alticinae David G. Furth Division of Entomology, Peabody Museum of Natural History, Yale University, New Haven, Connecticut 06511, U.S.A ABSTRACT. - Study of the 30 Palearctic and approximately 43 Nearctic genera of Alticinae reveals some relationships previously undetected. Examination of external and internal morphology, including male and female genitalia and the metafemoral spring, indicate synonymy or close relationship of a few Palearctic and Nearotic genera. Certain closely related genera are studied: Ores tioides Orestia, Hornaltica-Ochrosis, Macro/tat tica-Attica, Kuschetina-Capraita and Oedionychus, Asphaera-Omophoita. Results sug gest that Orthattica is not an Alticinae. Zoogeographic patterns of genera are also useful in evaluation of possible relation ships. As with most large families of insects the Chrysomelidae fauna of the Palearctic Region is better known than any other major biogeogra phic region of the world. This is certainly the case at the generic level. This is because of a historical preponderance of Palearctic entomolo gists since the time of Linnaeus, and the fact that the diversity is lower there relative to other major regions. The Nearctic Region is probably the next best known for chrysomelid faunistics and systematics, and although it is considerably less understood than the Palearctic at the species level, the genera are well known. There is also evidence of a Palearctic and Nearctic faunal connection through Laurasia during the Tertiary and across the Bering Straits during the Quaternary.