Egg Cannibalism by Passion Vine Specialist Disonycha Chevrolat Beetles

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Growing a Wild NYC: a K-5 Urban Pollinator Curriculum Was Made Possible Through the Generous Support of Our Funders

A K-5 URBAN POLLINATOR CURRICULUM Growing a Wild NYC LESSON 1: HABITAT HUNT The National Wildlife Federation Uniting all Americans to ensure wildlife thrive in a rapidly changing world Through educational programs focused on conservation and environmental knowledge, the National Wildlife Federation provides ways to create a lasting base of environmental literacy, stewardship, and problem-solving skills for today’s youth. Growing a Wild NYC: A K-5 Urban Pollinator Curriculum was made possible through the generous support of our funders: The Seth Sprague Educational and Charitable Foundation is a private foundation that supports the arts, housing, basic needs, the environment, and education including professional development and school-day enrichment programs operating in public schools. The Office of the New York State Attorney General and the New York State Department of Environmental Conservation through the Greenpoint Community Environmental Fund. Written by Nina Salzman. Edited by Sarah Ward and Emily Fano. Designed by Leslie Kameny, Kameny Design. © 2020 National Wildlife Federation. Permission granted for non-commercial educational uses only. All rights reserved. September - January Lesson 1: Habitat Hunt Page 8 Lesson 2: What is a Pollinator? Page 20 Lesson 3: What is Pollination? Page 30 Lesson 4: Why Pollinators? Page 39 Lesson 5: Bee Survey Page 45 Lesson 6: Monarch Life Cycle Page 55 Lesson 7: Plants for Pollinators Page 67 Lesson 8: Flower to Seed Page 76 Lesson 9: Winter Survival Page 85 Lesson 10: Bee Homes Page 97 February -

The Genome of the Colorado Potato Beetle, Leptinotarsa Decemlineata (Coleoptera: Chrysomelidae)

Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory Recent Work Title A model species for agricultural pest genomics: the genome of the Colorado potato beetle, Leptinotarsa decemlineata (Coleoptera: Chrysomelidae). Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/8bt5g4s4 Journal Scientific reports, 8(1) ISSN 2045-2322 Authors Schoville, Sean D Chen, Yolanda H Andersson, Martin N et al. Publication Date 2018-01-31 DOI 10.1038/s41598-018-20154-1 Peer reviewed eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California www.nature.com/scientificreports OPEN A model species for agricultural pest genomics: the genome of the Colorado potato beetle, Received: 17 October 2017 Accepted: 13 January 2018 Leptinotarsa decemlineata Published: xx xx xxxx (Coleoptera: Chrysomelidae) Sean D. Schoville 1, Yolanda H. Chen2, Martin N. Andersson3, Joshua B. Benoit4, Anita Bhandari5, Julia H. Bowsher6, Kristian Brevik2, Kaat Cappelle7, Mei-Ju M. Chen8, Anna K. Childers 9,10, Christopher Childers 8, Olivier Christiaens7, Justin Clements1, Elise M. Didion4, Elena N. Elpidina11, Patamarerk Engsontia12, Markus Friedrich13, Inmaculada García-Robles 14, Richard A. Gibbs15, Chandan Goswami16, Alessandro Grapputo 17, Kristina Gruden18, Marcin Grynberg19, Bernard Henrissat20,21,22, Emily C. Jennings 4, Jefery W. Jones13, Megha Kalsi23, Sher A. Khan24, Abhishek Kumar 25,26, Fei Li27, Vincent Lombard20,21, Xingzhou Ma27, Alexander Martynov 28, Nicholas J. Miller29, Robert F. Mitchell30, Monica Munoz-Torres31, Anna Muszewska19, Brenda Oppert32, Subba Reddy Palli 23, Kristen A. Panflio33,34, Yannick Pauchet 35, Lindsey C. Perkin32, Marko Petek18, Monica F. Poelchau8, Éric Record36, Joseph P. Rinehart10, Hugh M. Robertson37, Andrew J. Rosendale4, Victor M. Ruiz-Arroyo14, Guy Smagghe 7, Zsofa Szendrei38, Gregg W.C. -

Insects for Weed Control: Status in North Dakota

Insects for Weed Control: Status in North Dakota E. U. Balsbaugh, Jr. Associate Professor, Department of Entomology R. D. Frye Professor, Department of Entomology C. G. Scholl Plant Protection Specialist, North Dakota State Department of Agriculture A. W. Anderson Associate Professor, Department of Entomology Two foreign species of weevils have been introduced into North Dakota for the biological control of musk thistle, Carduus nutans L. - Rhinocyllus conicus (Froelich), a seed feeding weevH, and Ceutorrhynchidius horridus (Panzer), an internal root and lower stem inhabiting species. R. conicus has survived for several generations and is showing some promise for thistle suppression in Walsh County, but releases of C. hor ridus have been unsuccessful. The pigweed nea beetle, Disonycha glabrata (Fab.), which is native in southern United States, has been introduced into experimental sugarbeet plots in the Red River Valley for testing its effects at controlling rough pigweed or redroot, Amaranthus retroflexus L. Although both larvae and adults of these beetles feed heavily on pigweed, damage to the weed occurs too late in the season for them to be effective in suppressing weed growth or seed set. An initial survey for native insects of bindweed has been conducted. Feeding by localized populations of various insects, particularly tortoise beetles, has been observed. Several foreign species of nea beetles and a stem boring beetle are anticipated for release against leafy spurge. Entomologists at North Dakota State University are successful. In 1940, the cactus-feeding moth, Cac studying insects that feed on weeds to determine if the toblastis cactorum (Berg), was transported from its insects can reduce populations of selected weeds to native Argentina to Australia where it greatly reduced levels at which the weeds no longer are economically im the numbers of prickly pear cactus, Opuntia spp. -

Consumption of Bird Eggs by Invasive

WWW.IRCF.ORG/REPTILESANDAMPHIBIANSJOURNALTABLE OF CONTENTS IRCF REPTILES IRCF& AMPHIBIANS REPTILES • VOL &15, AMPHIBIANS NO 4 • DEC 2008 • 19(1):64–66189 • MARCH 2012 IRCF REPTILES & AMPHIBIANS CONSERVATION AND NATURAL HISTORY TABLE OF CONTENTS INTRODUCED SPECIES FEATURE ARTICLES . Chasing Bullsnakes (Pituophis catenifer sayi) in Wisconsin: On the Road to Understanding the Ecology and Conservation of the Midwest’s Giant Serpent ...................... Joshua M. Kapfer 190 . The Shared HistoryConsumption of Treeboas (Corallus grenadensis) and Humans on ofGrenada: Bird Eggs A Hypothetical Excursion ............................................................................................................................Robert W. Henderson 198 byRESEARCH Invasive ARTICLES Burmese Pythons in Florida . The Texas Horned Lizard in Central and Western Texas ....................... Emily Henry, Jason Brewer, Krista Mougey, and Gad Perry 204 1 2 3 . The Knight Anole (Anolis equestrisCarla) inJ. Florida Dove , Robert N. Reed , and Ray W. Snow .............................................Brian J. Camposano, Kenneth L. Krysko, Kevin M. Enge, Ellen M. Donlan, and Michael Granatosky 212 1 SmithsonianCONSERVATION Institution, Division ALERT of Birds, NHB E-600, MRC 116, Washington, District of Columbia 20560, USA ([email protected]) 2U.S. Geological Survey, Fort Collins Science Center, 2150 Centre Ave, Bldg C, Fort Collins, Colorado 80526, USA ([email protected]) . World’s Mammals in Crisis ............................................................................................................................................................ -

Chrysomelidae, Coleoptera)

THE DONACIINAE, CRIOCERINAE, CLYTRINAE, - ~ CHLAMISINAE, EUMOLPINAE, AND CHRYSOMELINAE OF OKLAHOMA (CHRYSOMELIDAE, COLEOPTERA) by JAMES HENRY SHADDY \\ Bachelor of Science Oklahoma State University Stillwater, Oklahoma Submitted to the faculty of the Graduate School of the Oklahoma State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF SCIENCE August, 1964 I OKLAHOMA lfAT&: UNNE.RSITf . LIBRARY JAN 8 lSGS THE DONACIINAE, CRIOCERINAE, CLYTRINAE, CHLAMISINAE, EUMOLPINAE, AND CHRYSOMELINAE OF OKLAHOMA (CHRYSOMELIDAE, COLEOPTERA) Thesis Approved: 570350 ii TABLE OF CONTENTS Page INTRODUCTION ..... 1 REVIEW OF THE LITERATURE 3 SYSTEMATICS ... 4 LITERATURE CITED 45 ILLUSTRATIONS 47 INDEX • • • . 49 iii INTRODUCTION The leaf beetles form a conspicuous segment of the coleopterous fauna of Oklahoma. Because no taxonomic paper on the Chrysomelidae existed for the state, the present work with the subfamilies Donaciinae, Criocerinae, Clytrinae, Chlamisinae, Eumolpinae, and Chrysomelinae of the eleven subfamilies found in Oklahoma was inaugurated. The chrysomelids are a large family of small or medium-sized beetles. They are generally host specific and sometimes cause extensive damage to field crops and horticultural plants. However, the Donaciinae, Clytrinae, and Chlamisinae are of little economic interest. The economically important species belong to the Criocerinae, Eumolpinae, and·Chrysomelinae. The larvae and adults of these feed on the foliage of plants, except the larvae of Eumolpinae which are primarily rootfeeders. Included in this work are 29 genera contain- ing 59 species of which 54 species are known to occur in the state and five. species are likely to occur here. I wish to thank my major advisor, Dr. William A. Drew, for his encouragement, guidance and assistance, and the other committee members, Drs. -

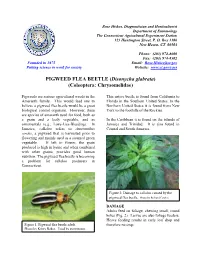

PIGWEED FLEA BEETLE (Disonycha Glabrata) (Coleoptera: Chrysomelidae)

Rose Hiskes, Diagnostician and Horticulturist Department of Entomology The Connecticut Agricultural Experiment Station 123 Huntington Street, P. O. Box 1106 New Haven, CT 06504 Phone: (203) 974-8600 Fax: (203) 974-8502 Founded in 1875 Email: [email protected] Putting science to work for society Website: www.ct.gov/caes PIGWEED FLEA BEETLE (Disonycha glabrata) (Coleoptera: Chrysomelidae) Pigweeds are serious agricultural weeds in the This native beetle is found from California to Amaranth family. This would lead one to Florida in the Southern United States. In the believe a pigweed flea beetle would be a great Northern United States it is found from New biological control organism. However, there York to the foothills of the Rockies. are species of amaranth used for food, both as a grain and a leafy vegetable, and as In the Caribbean it is found on the islands of ornamentals (e.g., Love-Lies-Bleeding). In Jamaica and Trinidad. It is also found in Jamaica, callaloo refers to Amaranthus Central and South America. viridis, a pigweed that is harvested prior to flowering and mainly used as a steamed green vegetable. If left to flower, the grain produced is high in lysine and when combined with other grains, provides good human nutrition. The pigweed flea beetle is becoming a problem for callaloo producers in Connecticut. Figure 2. Damage to callaloo caused by the pigweed flea beetle. Photo by Richard Cowles. DAMAGE Adults feed on foliage, chewing small, round holes (Fig. 2). Larvae are also foliage feeders. Heavy feeding results in early leaf drop and Figure 1. -

Saving the Mountain Chicken

Saving the mountain chicken Long-Term Recovery Strategy for the Critically Endangered mountain chicken 2014-2034 Adams, S L, Morton, M N, Terry, A, Young, R P, Dawson, J, Martin, L, Sulton, M, Hudson, M, Cunningham, A, Garcia, G, Goetz, M, Lopez, J, Tapley, B, Burton, M and Gray, G. Front cover photograph Male mountain chicken. Matthew Morton / Durrell (2012) Back cover photograph Credits All photographs in this plan are the copyright of the people credited; they must not be reproduced without prior permission. Recommended citation Adams, S L, Morton, M N, Terry, A, Young, R P, Dawson, J, Martin, L, Sulton, M, Cunningham, A, Garcia, G, Goetz, M, Lopez, J, Tapley, B, Burton, M, and Gray, G. (2014). Long-Term Recovery Strategy for the Critically Endangered mountain chicken 2014-2034. Mountain Chicken Recovery Programme. New Information To provide new information to update this Action Plan, or correct any errors, e-mail: Jeff Dawson, Amphibian Programme Coordinator, Durrell Wildlife Conservation Trust, [email protected] Gerard Gray, Director, Department of Environment, Ministry of Agriculture, Land, Housing and Environment, Government of Montserrat. [email protected] i Saving the mountain chicken A Long-Term Recovery Strategy for the Critically Endangered mountain chicken 2014-2034 Mountain Chicken Recovery Programme ii Forewords There are many mysteries about life and survival on Much and varied research and work needs continue however Montserrat for animals, plants and amphibians. In every case before our rescue mission is achieved. The chytrid fungus survival has been a common thread in the challenges to life remains on Montserrat and currently there is no known cure. -

Timing of Metamorphosis in a Freshwater Crustacean: Comparison with Anuran Models Saran Twombly Ecology, Vol. 77, No. 6. (Sep., 1996), Pp

Timing of Metamorphosis in a Freshwater Crustacean: Comparison with Anuran Models Saran Twombly Ecology, Vol. 77, No. 6. (Sep., 1996), pp. 1855-1866. Stable URL: http://links.jstor.org/sici?sici=0012-9658%28199609%2977%3A6%3C1855%3ATOMIAF%3E2.0.CO%3B2-A Ecology is currently published by Ecological Society of America. Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of JSTOR's Terms and Conditions of Use, available at http://www.jstor.org/about/terms.html. JSTOR's Terms and Conditions of Use provides, in part, that unless you have obtained prior permission, you may not download an entire issue of a journal or multiple copies of articles, and you may use content in the JSTOR archive only for your personal, non-commercial use. Please contact the publisher regarding any further use of this work. Publisher contact information may be obtained at http://www.jstor.org/journals/esa.html. Each copy of any part of a JSTOR transmission must contain the same copyright notice that appears on the screen or printed page of such transmission. The JSTOR Archive is a trusted digital repository providing for long-term preservation and access to leading academic journals and scholarly literature from around the world. The Archive is supported by libraries, scholarly societies, publishers, and foundations. It is an initiative of JSTOR, a not-for-profit organization with a mission to help the scholarly community take advantage of advances in technology. For more information regarding JSTOR, please contact [email protected]. http://www.jstor.org Thu Mar 6 10:36:17 2008 Ecology, 77(6), 1996, pp. -

Nutrional Ecology in Social Insects

NUTRIONAL ECOLOGY IN SOCIAL INSECTS Laure-Anne Poissonnier Thesis submitted the 16th of July 2018 for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Department of Agricultural Science School of Agriculture, Food and Wine Faculty of Sciences, The University of Adelaide Supervisors: Jerome Buhl and Audrey Dussutour “If all mankind were to disappear, the world would regenerate back to the rich state of equilibrium that existed ten thousand years ago. If insects were to vanish, the environment would collapse into chaos.” E.O.Wilson Table of Contents Tables of contents i Abstract v Declaration vii Acknowledgements ix Statements of authorship x Chapter 1 – General introduction 1 1. Nutrition is a complex process that influences and links all living organisms 3 2. Towards an integrative approach to study nutrition, the Nutritional Geometric Framework 4 2.a. Nutrient regulation 5 2.b. Nutrient effects on life history traits and feeding rules 8 3. Nutrition and sociality 10 3.a. Nutrition and immunity in social insects 12 3.a. Humoral and cellular defence against pathogens in insects 13 3.b Behavioural strategies used by social insects to fight parasites 14 3.c Physiological strategies used by social insects to fight parasites 16 3.d Role of nutrition in insects’ immunity 16 4. Nutrition in insect colonies 18 4.a. Self-organisation and foraging in social insects 19 4.b. Ending mass recruitment 21 4.c. Modulating recruitment according to food quality 22 4.d. Information exchange and food sharing between castes 23 4.e. Distribution of nutrients in the colony 25 4.f. The insight brought by NGF studies in social insect nutrition 29 5. -

'Entomophagy': an Evolving Terminology in Need of Review

"Entomophagy" an evolving terminology in need of review Evans, Joshua David; Alemu, Mohammed Hussen; Flore, Roberto; Frøst, Michael Bom; Halloran, Afton Marina Szasz; Jensen, Annette Bruun; Maciel Vergara, Gabriela; Meyer- Rochow, V.B.; Münke-Svendsen, C.; Olsen, Søren Bøye; Payne, C.; Roos, Nanna; Rozin, P.; Tan, H.S.G.; van Huis, Arnold; Vantomme, Paul; Eilenberg, Jørgen Published in: Journal of Insects as Food and Feed DOI: 10.3920/JIFF2015.0074 Publication date: 2015 Document version Publisher's PDF, also known as Version of record Citation for published version (APA): Evans, J. D., Alemu, M. H., Flore, R., Frøst, M. B., Halloran, A. M. S., Jensen, A. B., Maciel Vergara, G., Meyer- Rochow, V. B., Münke-Svendsen, C., Olsen, S. B., Payne, C., Roos, N., Rozin, P., Tan, H. S. G., van Huis, A., Vantomme, P., & Eilenberg, J. (2015). "Entomophagy": an evolving terminology in need of review. Journal of Insects as Food and Feed, 1(4), 293-305. https://doi.org/10.3920/JIFF2015.0074 Download date: 26. Sep. 2021 Wageningen Academic Journal of Insects as Food and Feed, 2015; 1(4): 293-305 Publishers ‘Entomophagy’: an evolving terminology in need of review J. Evans1*, M.H. Alemu2, R. Flore1, M.B. Frøst1, A. Halloran3, A.B. Jensen4, G. Maciel-Vergara4, V.B. Meyer-Rochow5,6, C. Münke-Svendsen7, S.B. Olsen2, C. Payne8, N. Roos3, P. Rozin9, H.S.G. Tan10, A. van Huis11, P. Vantomme12 and J. Eilenberg4 1Nordic Food Lab, University of Copenhagen, Department of Food Science, Rolighedsvej 30, 1958 Frederiksberg C, Copenhagen, Denmark; 2University of Copenhagen, -

'Entomophagy': an Evolving Terminology in Need of Review

"Entomophagy" an evolving terminology in need of review Evans, Joshua David; Alemu, Mohammed Hussen; Flore, Roberto; Frøst, Michael Bom; Halloran, Afton Marina Szasz; Jensen, Annette Bruun; Maciel Vergara, Gabriela; Meyer- Rochow, V.B.; Münke-Svendsen, C.; Olsen, Søren Bøye; Payne, C.; Roos, Nanna; Rozin, P.; Tan, H.S.G.; van Huis, Arnold; Vantomme, Paul; Eilenberg, Jørgen Published in: Journal of Insects as Food and Feed DOI: 10.3920/JIFF2015.0074 Publication date: 2015 Document version Publisher's PDF, also known as Version of record Citation for published version (APA): Evans, J. D., Alemu, M. H., Flore, R., Frøst, M. B., Halloran, A. M. S., Jensen, A. B., Maciel Vergara, G., Meyer- Rochow, V. B., Münke-Svendsen, C., Olsen, S. B., Payne, C., Roos, N., Rozin, P., Tan, H. S. G., van Huis, A., Vantomme, P., & Eilenberg, J. (2015). "Entomophagy": an evolving terminology in need of review. Journal of Insects as Food and Feed, 1(4), 293-305. https://doi.org/10.3920/JIFF2015.0074 Download date: 28. sep.. 2021 Wageningen Academic Journal of Insects as Food and Feed, 2015; 1(4): 293-305 Publishers ‘Entomophagy’: an evolving terminology in need of review J. Evans1*, M.H. Alemu2, R. Flore1, M.B. Frøst1, A. Halloran3, A.B. Jensen4, G. Maciel-Vergara4, V.B. Meyer-Rochow5,6, C. Münke-Svendsen7, S.B. Olsen2, C. Payne8, N. Roos3, P. Rozin9, H.S.G. Tan10, A. van Huis11, P. Vantomme12 and J. Eilenberg4 1Nordic Food Lab, University of Copenhagen, Department of Food Science, Rolighedsvej 30, 1958 Frederiksberg C, Copenhagen, Denmark; 2University of -

Flea Beetles

E-74-W Vegetable Insects Department of Entomology FLEA BEETLES Rick E. Foster and John L. Obermeyer, Extension Entomologists Several species of fl ea beetles are common in Indiana, sometimes causing damage so severe that plants die. Flea beetles are small, hard-shelled insects, so named because their enlarged hind legs allow them to jump like fl eas from plants when disturbed. They usually move by walking or fl ying, but when alarmed they can jump a considerable distance. Most adult fl ea beetle damage is unique in appearance. They feed by chewing a small hole (often smaller than 1/8 inch) in a leaf, moving a short distance, then chewing another hole and so on. The result looks like a number of “shot holes” in the leaf. While some of the holes may meet, very often they do not. A major exception to this characteristic type of damage is that caused by the corn fl ea beetle, which eats the plant tissue forming narrow lines in the corn leaf surface. This damage gives plants a greyish appearance. Corn fl ea beetle damage on corn leaf (Photo Credit: John Obermeyer) extent of damage is realized. Therefore, it is very important to regularly check susceptible plants, especially when they are in the seedling stage. Most species of fl ea beetles emerge from hibernation in late May and feed on weeds and other plants, if hosts are not available. In Indiana, some species have multiple generations per year, and some have only one. Keeping fi elds free of weed hosts will help reduce fl ea beetle populations.