Eudora Welty As Photographer, P

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Galerie Karsten Greve Ag

GALERIE KARSTEN GREVE AG Louise Bourgeois, New Orleans, oil on cardboard, 1946, 66 x 55.2 cm / 26 x 21 1/4 in LOUISE BOURGEOIS December 19, 2020 – extended until March 30, 2021 Opening: Tuesday, December 29, 2020, 11 am – 7 pm Galerie Karsten Greve AG is delighted to present its third solo exhibition of works by Louise Bourgeois (1911-2010) in its St. Moritz gallery space. Twenty-three distinctive pieces created during a period of six decades (1946-2007) are on show. The exhibition pays homage to one of the most significant artists of our time, reflecting thirty years of close collaboration between Galerie Karsten Greve and Louise Bourgeois. Following the artist’s first retrospective in Europe, shown at Frankfurter Kunstverein in 1989, Karsten Greve organized his first solo show of works by Louise Bourgeois in his recently opened Paris exhibition space in 1990. On the occasion of the opening of his gallery in St. Moritz in 1999, Karsten Greve dedicated a comprehensive show to the artist, followed by presentations in Paris and Cologne. Born in Paris in 1911, Louise Bourgeois grew up in a bourgeois family in Choisy-le-Roi near Paris, where her parents ran a workshop for restoring tapestries; at an early age, she made the drawings for missing sections in tapestry designs. After dropping out of mathematics at the Sorbonne, she completed her art studies, between 1932 and 1938, at the École des Beaux-Arts and selected studios and academies in Paris, taking lessons with Fernand Léger, among others. In 1938, she was married to Robert Goldwater, the American art historian, and went with him to New York. -

Galerie Karsten Greve

GALERIE KARSTEN GREVE Georgia Russell in her studio, Méru, 2021 photo: Nicolas Brasseur, Courtesy Galerie Karsten Greve, Cologne Paris St. Moritz GEORGIA RUSSELL Ajouré September, 3 – October 30, 2021 Opening on Friday, September 3, 2021, 11 am – 10 pm a DC OPEN GALLERIES 2021 event The artist will be present. Galerie Karsten Greve is delighted to show a solo exhibition featuring new work by Scottish artist Georgia Russell, who has been represented by the gallery since 2010. The show, which will be Georgia Russell's sixth solo exhibition with Galerie Karsten Greve, is a DC OPEN GALLERIES 2021 event. New works on canvas will be presented, created at her Méru studio between 2020 and 2021 during a worldwide state of crisis that was characterised by confinement and social distancing measures. By contrast, Georgia Russell has created her most recent works by breaking through matter. Her pieces epitomise the idea of the permeability of matter and breaking through the surface – ajouré – to bring this materiality to life by deliberately incorporating daylight and air into space. Born in Elgin, Scotland, in 1974, Georgia Russell, studied fine art at the Robert Gordons University of Aberdeen (until 1997) and the Royal College of Art, graduating with an MA in printmaking in 2000. Thanks to a scholarship from the Royal College of Art, the artist set up a studio in Paris. Her work has regularly been presented internationally in solo and group exhibitions. Works by Georgia Russell are also held in notable private and public collections, such as the Victoria & Albert Museum, London, the Centre Georges Pompidou, Paris, the E.On Art Collection, Düsseldorf, and the Museum Pfalzgalerie Kaiserslautern. -

The Importance of the Catholic School Ethos Or Four Men in a Bateau

THE AMERICAN COVENANT, CATHOLIC ANTHROPOLOGY AND EDUCATING FOR AMERICAN CITIZENSHIP: THE IMPORTANCE OF THE CATHOLIC SCHOOL ETHOS OR FOUR MEN IN A BATEAU A dissertation submitted to the Kent State University College of Education, Health, and Human Services in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy By Ruth Joy August 2018 A dissertation written by Ruth Joy B.S., Kent State University, 1969 M.S., Kent State University, 2001 Ph.D., Kent State University, 2018 Approved by _________________________, Director, Doctoral Dissertation Committee Natasha Levinson _________________________, Member, Doctoral Dissertation Committee Averil McClelland _________________________, Member, Doctoral Dissertation Committee Catherine E. Hackney Accepted by _________________________, Director, School of Foundations, Leadership and Kimberly S. Schimmel Administration ........................ _________________________, Dean, College of Education, Health and Human Services James C. Hannon ii JOY, RUTH, Ph.D., August 2018 Cultural Foundations ........................ of Education THE AMERICAN COVENANT, CATHOLIC ANTHROPOLOGY AND EDUCATING FOR AMERICAN CITIZENSHIP: THE IMPORTANCE OF THE CATHOLIC SCHOOL ETHOS. OR, FOUR MEN IN A BATEAU (213 pp.) Director of Dissertation: Natasha Levinson, Ph. D. Dozens of academic studies over the course of the past four or five decades have shown empirically that Catholic schools, according to a wide array of standards and measures, are the best schools at producing good American citizens. This dissertation proposes that this is so is partly because the schools are infused with the Catholic ethos (also called the Catholic Imagination or the Analogical Imagination) and its approach to the world in general. A large part of this ethos is based upon Catholic Anthropology, the Church’s teaching about the nature of the human person and his or her relationship to other people, to Society, to the State, and to God. -

Photographs New York | March 30, 2020

Photographs New York | March 30, 2020 Photographs New York I Monday March 30, 2020, at 2pm EST BONHAMS BIDS INQUIRIES 580 Madison Avenue +1 (212) 644 9001 Laura Paterson New York, New York 10022 +1 (212) 644 9009 fax Head of Photographs bonhams.com [email protected] +1 (917) 206 1653 [email protected] PREVIEW To bid via the internet please visit New York www.bonhams.com/25760 Amelia Wilson Photographs Cataloguer Thursday March 26, 10am to 5pm Please note that bids should be +1 (917) 206 1635 Friday March 27, 10am to 5pm summitted no later than 24 hours [email protected] Saturday March 28, 12pm to 5pm prior to the sale. New Bidders must Sunday March 29, 12pm to 5pm also provide proof of identity when Monday March 30, 10am to 12pm SALE INCLUDING submitting bids. Failure to do this COLLECTIONS OF may result in your bid not being 25760 • The Pritzker Organization, SALE NUMBER: processed. Lots 1 - 176 Chicago • The Collection of James (Jimmy) LIVE ONLINE BIDDING IS Fox CATALOG: $35 AVAILABLE FOR THIS SALE Please email bids.us@bonhams. REGISTRATION ILLUSTRATIONS com with “Live bidding” in the IMPORTANT NOTICE Front cover: lot 37 subject line 48 hours before the Please note that all customers, Inside front cover: lot 23 auction to register for this service. irrespective of any previous activity Session page: lot 24 with Bonhams, are required to Inside back cover: lot 45 Bidding by telephone will only be complete the Bidder Registration Back cover: lot 124 accepted on a lot with a lower Form in advance of the sale. -

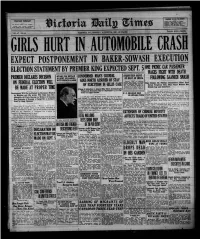

Expect Postponement in Barer Execution

WHERE T0_G0 TO-NIGHT WEATHER FORECAST Capitol—“The Making of0’M**ley rolembln—The Yankee Consul. _ . „ Dominion—"NWÿt Mfe In N.w Tort- Coliseum—"Lend Me YourWIfe.^ For 36 hours ending 5 pm, Tuesday: Victoria and vicinity — Southerly winds, cloudy and coo) with showers t>RICE FIVE CENTS VICTORIA, B.C., MONDAY, AUGUST 24, 1925 —16 PAGES VOL. 67 NO. 46 EXPECT POSTPONEMENT IN BARER EXECUTION ELECTION STATEMENT BY PREMIER KING EXPECTED SEPT, 5 mam SPEAKS FOR BRITAIN CONDEMNED MAN’S COUNSEL EIGHTEEN HURT PREMIER DECLARES DECISION IN DEBT EXCHANGES IN RIOT IN INDIA ti FOLLOWING SAANICH SMASH WITH FRENCH LEADER GOES NORTH ASSURED OF STAY Calcutta. Aug. 24.—Eighteen persons were Injured In serious rioting between Hindus and Mos Mi— Evelyn M. Phillips Unconscious Since Auto ON FEDERAL ELECTION WILL lems at Tagorgh. near here, to Struck Telephone Pole; Miss Jennie McGaw Has OF EXECUTION IN GILLIS CASE day. The Moslems charged the Hindus were carrying an Idol In a procession and played music aa Broken Leg and Collarbone. BE MADE AT PROPER TIE Filing of Intention to App May Have Automatically the procession passed a mosque. Postponed Execution 6 for September 4, it is Be- With a fractured skull sustained early yesterday morning in Government Will Not be Bushed by Discussion Started lieved in Legal Circles a motor accident on the West Saanich Road, Miss Evelyn Maude W. H. MILLMAN DIED Phillips, twenty-three, is waging a battle for life at the Royal by Meighen and His Aides; Will Take Into Con IN ONTARIO TOWN Jubilee Hospital. -

Galerie Karsten Greve

GALERIE KARSTEN GREVE GALERIE KARSTEN GREVE Drawing Now 2019 PIERRETTE BLOCH Dossier de Presse 5, RUE DEBELLEYME F-75003 PARIS TEL +33-(0)1-42 77 19 37 FAX +33-(0)1-42 77 05 58 [email protected] GALERIE KARSTEN GREVE GALERIE KARSTEN GREVE Stand A4 Solo show Pierrette Bloch L’Exposition Depuis bientôt dix ans, Karsten Greve soutient avec engagement le travail de Pierrette Bloch et défend avec passion sa démarche artistique pionnière, fondée sur la réitération d’un geste jamais égal à lui-même. Pour la troisième fois la galerie participera à la foire du dessin contemporain Drawing Now, au Carreau du Temple du 28 au 31 mars, avec une exposition monographique en hommage à Pierrette Bloch, dont l’œuvre avait déjà été choisie pour la section Masters Now de la foire en 2017. Nous présentons une sélection d’œuvres dont une partie issue de l’exposition « Ce n’est que moi », hommage de la ville de Bages à Pierrette Bloch. A travers Pierrette Bloch et ses amis artistes cette exposition de 2018 à la Maison des Arts mettait à l’honneur l’œuvre pionnière de l’artiste et surtout l’admiration que ses pairs ont toujours eu pour son travail. Notre accrochage sera donc en dialogue avec celui de la Galerie Ceysson et Bénétière (stand B2), qui montrera quant à elle une sélection d’œuvres de Pierre Buraglio, Philippe Favier, Alain Lambilliotte, Jean- Michel Meurice et Claude Viallat également issues de l’exposition à la Maison des Arts de Bages et réalisées sur de papiers déjà appartenus à Pierrette. -

Anti-Defamation League

Jewish Privilege E. Michael Jones Fidelity Press 206 Marquette Avenue South Bend, Indiana 46617 www.culturewars.com www.fidelitypress.org © E. Michael Jones, 2019 All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without the prior permission of Fidelity Press. Contents What Is Hate Speech? The ADL and the FBI Online Hate Index Capistrano on Jewish Privilege Homosexual Proxy Warrior Chubby Lesbian Kike Who Defines Hate? What Is Hate Speech? In keeping with the so-called “Christchurch Call to Action” which flowed from a meeting of government officials and internet giants on May 15, 2019 in Paris, Facebook issued an internal document entitled “Hate Agent Policy Review,” which, according to Breitbart, which received a copy from a source inside Facebook, “outlines a series of ‘signals’ that Facebook uses to determine if someone ought to be categorized as a ‘hate agent’ and banned from the platform.”[1] The guidelines were simultaneously draconian and incoherent. You can be designated as a “hate agent” if “you praise the wrong individual, interview them, or appear at events alongside them.”[2] Hate agent status is evidently contagious because Facebook may designate you as a hate agent if you associate with a “Designated Hate Entity,” like the Englishman Tommy Robinson. You can also be designated a hate agent “merely for speaking neutrally about individuals and organizations that the social network considers hateful.” Facebook tagged someone in October of last year simply because he gave what they considered was a “neutral representation of John Kinsman,” who is a member of “Proud Boys,” a group which Facebook does not like and does not want you to like. -

Le Csvemporte Tout Comme Un Ouragan

ET GA GNEZ UN RAID RELEVEZ DANS LE DE LE SERT LIBYEN! CHALLENGE... Pour plus d’info: www.jeep.lu Le CSVemportetout lundi8juin2009N°392 commeunouragan Monde 10 Jamais le Partichrétien-socialn'avait Jean-Claude Juncker, Premierminis- àcepoint dominé uneélection. Le tredepuisquatorzeans,atoutes les Àlagarderie, le feu CSVaremporté hautlamainles légis- chancesdesesuccéderàlui-même. Il apiégéles enfants latives2009,obtenant26siègessur 60 s'estdit favorableàunereconduction àlaChambredes députés. À54ans, de la coalitionsortante. Pages2et 3 De la pluieet de la folie au Sports 14 Rock am Ring Federerentre dans la légendedutennis Tendances 18 La mode printemps- été2010sedévoile r ir sm tin rs ke TheProdigy sait yfaire pour chaufferune foulede80000 personnesavecses rythmes acérés. Celui qui se rend chaque année ceptionàla règle. Ilsétaient contents de vibrer avec ThePro- au Rock am Ring saittrèsbien 80 000àavoir fait le déplace- digy, Slipknot,The Killers,Pla- que la journéeyserapluvieuse. ment au Nürburgring, ne se sou- cebo,Billy Talent ou encore L'édition 2009 n'a pasfaitex- ciantnidel'eau ni du froid. Trop LimpBizkit. Page 25 RAMMSTEIN en concertàlaRockhal Rendez-vous en page 23 2 Spécial élections lundi8juin 2009 /www.lessentiel.lu Réactions Junckeraux commandes Jean-ClaudeJuncker se dit réconforté «Jesuisréconforté parcet d'un rouleau compresseur élan populaire.C'est un ré- sultat inattendu, eu égardà la situationdifficile quetra- LUXEMBOURG -En versentles Luxembourgeois. deux législatives, le CSV La coalitionest confirméede sera passéde19à façonéclatante.Demain (aujourd'hui), je verrai les 26 députés.Jean-Claude orientations àprendre avec Junckerest le grand le Grand-Duc». gagnantdejuin2009. ------------------------------- »dossiersur AndréHoffmann www.lessentiel.lu resteraindépendant «Jebriguerai monmandat, Élections 2009 » sinon ce ne serait pashon- nête vis-à-visdeceuxqui ontvotépournous. -

Comic Trans Presenting and Representing the Other in Stand-Up Comedy

2018 THESIS Comic Trans Presenting and Representing the Other in Stand-up Comedy JAMES LÓ RIEN MACDONALD LIVE ART AND PERFORMANCE STUDIES (LAPS) LIVE ART AND PERFORMANCE STUDIES (LAPS) 2018 THESIS Comic Trans Presenting and Representing the Other in Stand-up Comedy JAMES LÓ RIEN MACDONALD ABSTRACT Date: 22.09.2018 AUTHOR MASTER’S OR OTHER DEGREE PROGRAMME James Lórien MacDonald Live Art and Performance Studies (LAPS) NUMBER OF PAGES + APPENDICES IN THE TITLE OF THE WRITTEN SECTION/THESIS WRITTEN SECTION Comic Trans: Presenting and Representing the Other in 99 pages Stand- up Comedy TITLE OF THE ARTISTIC/ ARTISTIC AND PEDAGOGICAL SECTION Title of the artistic section. Please also complete a separate description form (for dvd cover). The artistic section is produced by the Theatre Academy. The artistic section is not produced by the Theatre Academy (copyright issues have been resolved). The final project can be The abstract of the final project can published online. This Yes be published online. This Yes permission is granted for an No permission is granted for an No unlimited duration. unlimited duration. This thesis is a companion to my artistic work in stand-up comedy, comprising artistic-based research and approaches comedy from a performance studies perspective. The question addressed in the paper and the work is “How is the body of the comedian part of the joke?” The first section outlines dominant theories about humour—superiority, relief, and incongruity—as a background the discussion. It touches on the role of the comedian both as untrustworthy, playful trickster, and parrhesiastes who speaks directly to power, backed by the truth of her lived experience. -

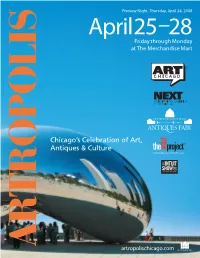

Artropolischicago.Com Friday Through Monday at The

Preview Night, Thursday, April 24, 2008 April 25–28 Friday through Monday at The Merchandise Mart artropolischicago.com April 25–28, 2008 at The Merchandise Mart Artropolis Tickets Good for admission to all five shows atT he Merchandise Mart Adults $20 daily or $25 multi-day pass Seniors, Students or Groups $15 multi-day pass Children 12 and under FREE Additional collegiate and high school information can be obtained by emailing [email protected] Tickets available online at artropolischicago.com Table of Contents 3 Welcome 19 Map 4 About the Exhibitions 21 Fine Art Museums 5 Art Chicago 22 Architecture and 8 NEXT Sculpture 10 The Merchandise Mart 23 Art Centers & Events International Antiques Fair 23 Dance 12 The Artist Project 24 Film 13 The Intuit Show of Folk 24 Institutions and Outsider Art 25 Museums 14 Program & Events 26 Music 14 Friday, April 25 27 Theatre 16 Saturday, April 26 29 Travel & Hotel Information 17 Sunday, April 27 30 Daily Schedules 18 Monday, April 28 Media Sponsor: Cover photo: Cloud Gate 18 Artropolis Cultural by Anish Kapoor at the AT&T Plaza in Millennium Park. Courtesy of the City of Chicago/Walter Mitchell Partners © 2008 Merchandise Mart Properties, Inc. 2 Welcome to Artropolis! There is no city as well-suited to host a major international art show as Chicago. It is home to top museums for modern and contemporary art, celebrated cultural institutions, thriving art galleries, and some of the world’s greatest artists, collectors and patrons. As Artropolis flourishes, it stimulates growth in each of the companion shows. -

Hoffman Vs Schoenberger 717 2020

Filing # 110428919 E-Filed 07/17/2020 04:21:30 PM IN THE CIRCUIT COURT OF THE 15TH JUDICIAL CIRCUIT, IN AND FOR PALM BEACH COUNTY, FLORIDA CASE NO.: 50-2019-CA-013860-XXXX-MB GABE HOFFMAN, an individual, Plaintiff, v. THOMAS SCHOENBERGER, an individual. Defendant. ________________________________________/ PLAINITFF’S MOTION FOR INJUNCTIVE RELIEF Pursuant to Florida Rule of Civil Procedure 1.610 and other applicable law, Plaintiff, Gabe Hoffman, (hereinafter “HOFFMAN”), hereby moves on the following grounds for an order of this Court, temporarily and permanently enjoining Defendant THOMAS SCHOENBERGER (hereinafter “SCHOENBERGER”) from taking certain actions more fully described below (the “Actionable Misconduct”) based on facts and circumstances herein presented, and those alleged in the complaint initiating this cause (the “Complaint”). INTRODUCTION AND OVERVIEW Factual Background of the Plaintiff 1. HOFFMAN is the founder of Accipiter Capital Management, LLC, (“Company”) which is a hedge fund, located in Palm Beach County, Florida. He is a highly respected and well known investment manager that regularly appears on television addressing a wide range of business issues and financial investments. He manages large sums of investor money and is a financial markets expert. 2. HOFFMAN’S livelihood and success are inextricably connected to his unassailable integrity and hard-won relationships to his investors. HOFFMAN maintains relationships with prominent and well-known individuals in the financial markets and financial management industry -

How to Get the Daily Stormer Be Found on the Next Page

# # Publishing online In print because since 2013, offline Stormer the (((internet))) & Tor since 2017. is censorship! The most censored publication in history Vol. 99 Daily Stormer ☦ Sunday Edition 07–14 Jul 2019 What is the Stormer? No matter which browser you choose, please continue to use Daily Stormer is the largest news publication focused on it to visit the sites you normally do. By blocking ads and track- racism and anti-Semitism in human history. We are signifi- ers your everyday browsing experience will be better and you cantly larger by readership than many of the top 50 newspa- will be denying income to the various corporate entities that pers of the United States. The Tampa Tribune, Columbus Dis- have participated in the censorship campaign against the Daily patch, Oklahoman, Virginian-Pilot, and Arkansas Democrat- Stormer. Gazette are all smaller than this publication by current read- Also, by using the Tor-based browsers, you’ll prevent any- ership. All of these have dozens to hundreds of employees one from the government to antifa from using your browsing and buildings of their own. All of their employees make more habits to persecute you. This will become increasingly rele- than anyone at the Daily Stormer. We manage to deliver im- vant in the years to come. pact greater than anyone in this niche on a budget so small you How to support the Daily Stormer wouldn’t believe. The Daily Stormer is 100% reader-supported. We do what Despite censorship on a historically unique scale, and The we do because we are attempting to preserve Western Civiliza- Daily Stormer becoming the most censored publication in his- tion.