Evolution of Instruments for Harvest of the Skin Grafts Original Article

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Absorbable Surgical Gut Suture

Food and Drug Administration, HHS § 878.4840 § 878.4800 Manual surgical instrument in subpart E of part 807 of this chapter, for general use. subject to the limitations in § 878.9. (a) Identification. A manual surgical [53 FR 23872, June 24, 1988, as amended at 61 instrument for general use is a non- FR 1123, Jan. 16, 1996; 66 FR 38803, July 25, powered, hand-held, or hand-manipu- 2001] lated device, either reusable or dispos- able, intended to be used in various § 878.4820 Surgical instrument motors general surgical procedures. The device and accessories/attachments. includes the applicator, clip applier, bi- (a) Identification. Surgical instrument opsy brush, manual dermabrasion motors and accessories are AC-pow- brush, scrub brush, cannula, ligature ered, battery-powered, or air-powered carrier, chisel, clamp, contractor, cu- devices intended for use during surgical rette, cutter, dissector, elevator, skin procedures to provide power to operate graft expander, file, forceps, gouge, in- various accessories or attachments to strument guide, needle guide, hammer, cut hard tissue or bone and soft tissue. hemostat, amputation hook, ligature Accessories or attachments may in- passing and knot-tying instrument, clude a bur, chisel (osteotome), knife, blood lancet, mallet, disposable dermabrasion brush, dermatome, drill or reusable aspiration and injection bit, hammerhead, pin driver, and saw needle, disposable or reusable suturing needle, osteotome, pliers, rasp, re- blade. tainer, retractor, saw, scalpel blade, (b) Classification. Class I (general con- scalpel handle, one-piece scalpel, snare, trols). The device is exempt from the spatula, stapler, disposable or reusable premarket notification procedures in stripper, stylet, suturing apparatus for subpart E of part 807 of this chapter the stomach and intestine, measuring subject to § 878.9. -

Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery

ORAL AND MAXILLOFACIAL SURGERY 3rd EDITION 2/2012 US Chapter Pages 1 BASIC SETS OMFS-SET 1-36 TELESCOPES AND INSTRUMENTS FOR FRAKT 37-54 2 ENDOSCOPIC FRACTURE TREATMENT TELESCOPES AND INSTRUMENTS FOR TMJ 55-60 3 ARTHROSCOPY OF TEMPOROMANDIBULAR JOINT TELESCOPES AND INSTRUMENTS FOR DENT 61-80 4 MAXILLARY ENDOSCOPY TELESCOPES AND INSTRUMENTS DENT-K 81-120 5 FOR DENTAL SURGERY TELESCOPES AND INSTRUMENTS SIAL 121-134 6 FOR SIALENDOSCOPY 7 FLEXIBLE ENDOSCOPES FL-E 135-142 8 HOSPITAL SUPPLIES HS 143-240 9 INSTRUMENTS FOR RHINOLOGY AND RHINOPLASTY N 241-298 10 BIPOLAR AND UNIPOLAR COAGULATION COA 299-312 11 HEADMIRRORS – HEADLIGHTS OMFS-J 313-324 12 AUTOFLUORESCENCE AF-INTRO, AF 325-342 13 HOLDING SYSTEMS HT 343-356 VISUALIZATION SYSTEMS OMFS-MICRO, OMFS-VITOM 357-378 14 FOR MICROSURGERY OMFS-UNITS-INTRO, UNITS AND ACCESSORIES U 1-54 15 OMFS-UNITS COMPONENTS OMFS-SP SP 1-58 16 SPARE PARTS KARL STORZ OR1 NEO™, TELEPRESENCE 17 HYGIENE, ENDOPROTECT1 ORAL AND MAXILLOFACIAL SURGERY 3rd EDITION 2/2012 US Important information for U.S. customers Note: Certain devices and references made herein to specific indications of use may have not received clearance or ap- proval by the United States Food and Drug Administration. Practitioners in the United States should first consult with their local KARL STORZ representative in order to ascertain product availability and specific labeling claims. Federal (USA) law restricts certain devices referenced herein to sale, distribution, and use by, or on the order of a physician, dentist, veterinarian, or other practitioner licensed by the law of the State in which she/he practices to use or order the use of the device. -

CPT Code Description Charge Amount 83498 17-Alpha

CPT Code Description Charge Amount 83498 17-alpha-Hydroxyprogester 308.41 83497 5-HIAA, SO 125.99 83516 A MYELOPEROX (MPO) AB QL 74.1 86021 AB ID LEUKOCYTE AB/SO 610.25 86022 AB ID, PLATELET ABS;SRA U 1318 86720 AB LEPTOSPIRA/SO 166.12 86850 AB SCREEN (IDC) 207.83 86850 AB SCREEN RBC EA SRM TECH 195.25 86793 AB, YERSINIA/SO 149 74018 ABDOMEN 1 VIEW 348.75 74018 ABDOMEN 1 VIEW PORTABLE 321.36 74022 ABDOMEN ACUTE COMP WSGL V 398.36 74019 ABDOMEN COMPLETE 398.36 74018 ABDOMEN SGL ANTEROPOSTERI 475.8 49083 ABDOMINAL PARACENTESIS W/ 1216.89 86870 ABID,WNJ 294.85 ABLATOR APOLLORF XL90 ASP 877.8 86900 ABO BLOOD TYPE 370 86900 ABO,BBSO 176.5 73050 AC JOINTS W/WO WEIGHTS BI 297.94 ACCUGRID RADIOGRAPH BREAS 121.36 82164 ACE, CSF SO 144.38 83519 ACHR BIND AB QT,RIA/SO MA 258 83519 ACHR BIND QNT MGP/SO 181.37 83519 ACHR BLOC QNT MGP/SO 181.37 83519 ACHR GANGL NEUR AB,RIA/SO 258 83519 ACHR MOD QNT MGP/SO 201.16 87116 ACID FAST CULTURE SO 227.33 83519 ACR BLOCKING QNT SO 181.37 83519 ACR RECEPTOR QNT SO 108.61 82024 ACTH,SO 459.3 86602 ACTINOMYCES AB/SO 64 85347 ACTIVATED CLOTTING TIME 126.93 85307 Activated Protein C Resis 216.04 97535GO ACTIVITY DAILY LIVING 15 265.91 78278 ACUTE GI BLOOD LOSS IMAGI 1326.15 82017 ACYLCARNITINES; QUANT, EA 574 85397 ADAMSTS 13 ACTIVITY/SO 796.62 ADAPTER CATH LUER 8.69 ADAPTER CONFIDENCE CEMENT 743.66 ADAPTER DLP PERFUS Y W/6 47.54 ADAPTER FIBEROPTIC SWIVEL 73.16 ADAPTER LUER LOC SHORT 3/ 2.2 ADAPTER LUER TO COLDER 15.29 ADAPTER MALE-MALE 4.57 C1776 ADAPTER PFC SIGMA FEMORAL 8474.76 ADAPTER PLUG MALE CLAVE 5.02 ADAPTER PRODIGY EXTENSION 2340 ADAPTER UROSTOMY DRAIN TU 9.09 ADAPTER VERSO AIRWAY ADUL 33.51 82952 ADDL GLUCOSE > 3 SPEC 136.24 87260 ADENOV/ RSPFAC / SO 141.75 ADHESIVE DEMABOND .07 PEN 193.48 ADHESIVE DEMABOND .07 PEN 193.48 ADHESIVE DERMABOND PEN 0. -

Hospitals for War-Wounded

hospitals_war_cover_april2003 9.6.2005 13:47 Page 1 ICRC HOSPITALS FOR WAR-WOUNDED HOSPITALS FORHOSPITALS WAR-WOUNDED This book is intended for anyone who is faced A practical guide for setting up with the task of setting up or running a hospital and running a surgical hospital which admits war-wounded. It is a practical guide in an area of armed conflict based on the experience of four nurses who have managed independent hospitals set up by the International Committee of the Red Cross. It addresses specific problems associated with setting up a hospital in a difficult and potentially dangerous environment. It provides a framework for the administration of such a hospital. It also describes a system for managing the patients from admission to discharge and includes guidelines on how to manage an influx of wounded. These guidelines represent a realistic and achievable standard of care whatever the circumstances. A practical guide 0714/002 05/2005 1000 HOSPITALS FOR WAR-WOUNDED International Committee of the Red Cross 19 Avenue de la Paix 1202 Geneva, Switzerland T +41 22 734 6001 F +41 22 733 2057 E-mail: [email protected] www.icrc.org # ICRC, April 2005, revised and updated edition This book is dedicated to the memory of Jo´n Karlsson (died in Afghanistan, 22 April 1992) Fernanda Calado Hans Elkerbout Ingebjørg Foss Nancy Malloy Gunnhild Myklebust Sheryl Thayer (died in Chechnya, 17 December 1996) HOSPITALS FOR WAR-WOUNDED A practical guide for setting up and running a surgical hospital in an area of armed conflict Jenny Hayward-Karlsson Sue Jeffery Ann Kerr Holger Schmidt INTERNATIONAL COMMITTEE OF THE RED CROSS ISBN 2-88145-094-6 # International Committee of the Red Cross, Geneva, 1998 WEB address: http://www.icrc.org CONTENTS vii CONTENTS FOREWORD ............................................ -

1779-80 Encampment

yr / 1 ■>**' / « * 2 T ¿ v/.- X» '.- .I 3 2 1 !1 3 7 9 ? 7 MORRISTOWN NATIONAL HISTORICAL PARK 1779-80 ENCAMPMENT A STUDY OF MEDICAL SERVICES APRIL 1971 MORRISTOWN NATIONAL HISTORICAL PARK 1779-80 ENCAMPMENT A STUDY OF MEDICAL SERVICES by RICARDO TORRES-REYES OFFICE OF HISTORY AND HISTORIC ARCHITECTURE EASTERN SERVICE CENTER WASHINGTON, D. C. APRIL 1971 UNITED STATES DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR NATIONAL PARK SERVICE Foreword This report on the medical services at Morristown during the winter encampment of 1779-80 was undertaken to restudy and evaluate the subject in the light of the standard practices of the Continental Army Medical Department. One phase of the evaluation is to determine if the existence and location of the present replica of the so-called Tilton Hospital in the Jockey Hollow area can be justified historically. For interpretive purposes, the report reviews the organic structure of the medical or hospital department, identifies and describes health problems and diseases, and outlines the medical resources of the military surgeons to combat incident diseases and preserve the health of the soldiers. Research on the subject was conducted at the Library of Congress, the National Archives, Pennsylvania Historical Society, American Philosophical Society, the Library Company of Philadelphia and the Morristown NHP library. Several persons contributed to the completion of this study. As usual, Superintendent Stephen H. Lewis and Historians Bruce W. Steward and Diana F. Skiles provided splendid cooperation during my stay in the park; Leah S. Burt, Assistant Park Archivist, located Dr. Cochran's "LetterBook" in the Morristown Public Library. In the National Archives, the diligent efforts of Miss Marie Bouhnight, Office of Old Military Records, resulted in locating much-needed hospital returns of Valley Forge, Middlebrook and Morristown. -

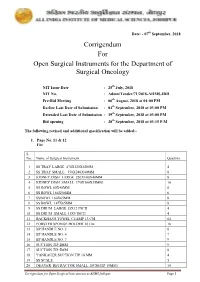

Corrigendum for Open Surgical Instruments for the Department Of

Date: - 07th September, 2018 Corrigendum For Open Surgical Instruments for the Department of Surgical Oncology NIT Issue Date : 25th July, 2018 NIT No. : Admn/Tender/71/2018-AIIMS.JDH Pre-Bid Meeting : 06th August, 2018 at 04:00 PM Earlier Last Date of Submission : 04th September, 2018 at 03:00 PM Extended Last Date of Submission : 19th September, 2018 at 03:00 PM Bid opening : 20th September, 2018 at 03:15 P.M The following revised and additional specification will be added:- 1. Page No. 11 & 12 For S. No. Name of Surgical Instrument Quantity 1 SS TRAY LARGE 470X320X50MM 4 2 SS TRAY SMALL 350X240X40MM 8 3 KIDNEY DISH LARGE 250X140X40MM 8 4 KIDNEY DISH SMALL 170X100X35MM 10 5 SS BOWL 80X40MM 6 6 SS BOWL 166X50MM 6 7 SSBOWL 160X65MM 8 8 SS BOWL 147X65MM 8 9 SS DRUM LARGE 15X12 INCH 4 10 SS DRUM SMALL 11X9 INCH 4 11 BACKHAUS TOWEL CLAMP 13 CM 64 12 FORSTER SPONGE HOLDER 18 Cm 18 13 BP HANDLE NO. 3 8 14 BP HANDLE NO. 4 7 15 BP HANDLE NO. 7 9 16 SUCTION TIP 2MM 9 17 SUCTION TIP 5MM 8 18 YANKAUER SUCTION TIP 10 MM 4 19 SS SCALE 5 20 DEAVER RETRACTOR SMALL 18CM(TIP 19MM) 14 Corrigendum for Open Surgical Instruments at AIIMS Jodhpur Page 1 21 DEAVER RETRACTOR MEDIUM 30.5CM (TIP 25 MM) 10 22 DEAVER RETRACTOR LARGE 31.5CM (TIP 50MM) 10 23 DOYEN’S RETRACTOR 4 24 MORRIS RETRACTOR 25cm ( BLADE 7x4cm) 6 25 SKIN HOOK 32 26 LANGENBECK RETRACTOR SMALL 16cm (TIP 21x 8mm) 16 27 LANGENBECK RETRACTOR MEDIUM 22cm (TIP 50x11mm) 16 28 LANGENBECK RETRACTOR LARGE 22.5cm (TIP 85x15mm) 14 29 C ZERNY RETRACTOR 17.2 cm 14 30 VEIN RETRACTOR 18 31 BALFOUR ABDOMINAL RETRACTOR 20cm 3 32 MASTOID RETRACTOR 4 33 PERIOSTEUM ELEVATOR SHARP 4 34 PERIOSTEUM ELEVATOR BLUNT 4 35 DISSECTING TOOTH FORCEPS 15 CM 16 36 DISSECTING PLAIN FORCEPS 18 CM 16 37 ARTERY FORCEPS CVD 15 CM 36 38 ARTERY FORCEPS ST. -

Healthcare Product Description Guideline

Canadian Healthcare Product Description Standardization Implementation Guidelines Version: 1.1 Updated: 2018 March Canadian Healthcare Product Description Standardization Implementation Guidelines Document Summary Document Item Current Value Document Name Canadian Healthcare Product Description Standardization Implementation Guidelines Document Version 1.1 Document Status Initial Publication December, 2010 Update formatting and appendix June 2016 Errata in abbreviation list “Universal” March 2018 Document Status FINAL Document Description Supplements the formal GS1 Canada Healthcare Supply Chain Guidelines January 2010 Version 1.0 providing information on the standardization of the short product description for the healthcare supply chain in Canada. Content Developers Organization Name 3M Canada Company Content Developer Ruth Wisotzki 3M Canada Company Content Developer Marilyn Piper HealthPRO Procurement Services Content Developer Ronda Harris HealthPRO Procurement Services Content Developer Tricia Cooper Medtronic Canada Inc. Content Developer Alain Boutin North Bay General Hospital Content Developer Lise Morris North York General Hospital Content Developer Marty McKinlay Ontario Hospital Association (OHA) Content Developer Peter Roman Source Medical Content Developer Anne Griffin Source Medical Content Developer Phil Kelly St. Michael’s Hospital Content Developer Diane Eley Toronto General Hospital (UHN) Content Developer Maria Masella Toronto General Hospital (UHN) Content Developer Wendy Watson Toronto Western Hospital (UHN) Content -

Retained Curved Needle After Balloon Kyphoplasty: a Complication with a Novel Device and Its Management

Open Access Case Report DOI: 10.7759/cureus.4367 Retained Curved Needle After Balloon Kyphoplasty: A Complication with a Novel Device and Its Management Neal A. Shah 1 , Eric Catlin 2 , Navdeep Jassal 3 , Osama Hafez 4 , Devang Padalia 5 1. Anesthesia and Interventional Pain Management, H. Lee Moffitt Cancer Center and Research Institute, Tampa, USA 2. Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation, University of South Florida, Tampa, USA 3. Pain Management, University of South Florida, Tampa, USA 4. Anesthesiology, H. Lee Moffitt Cancer Center and Research Institute, Tampa, USA 5. Anesthesia and Interventional Pain Management, H. Lee Moffitt Cancer Center and Research Institute, Ormond Beach, USA Corresponding author: Eric Catlin, [email protected] Abstract To date, no case studies specifically describing a curved kyphoplasty needle becoming lodged in the vertebral body with the inability to be withdrawn have been reported. We describe a case involving a single level balloon kyphoplasty with a curved coaxial needle during which the cement delivery device could not be removed after cavity filling. In this case, a board-certified interventional pain management specialist was performing balloon kyphoplasty for an L2 osteoporotic vertebral compression fracture. The tools utilized in this procedure included flexible curved instruments designed to traverse the vertebral body and achieve uniform cement distribution through a unipedicular approach. Cannulation and cavity formation were completed without issue. Upon conclusion of cement filling, the curved cement delivery device was unable to be removed. After several attempts to remove the needle and consultation with both the device company and local spine surgeons, it was agreed that the device should be cut at the level of entry into the pedicle and left as a retained foreign object. -

Post Mortem/ Autopsy

Xxxxxxg Post Mortem/ Autopsy Plastic/Oral Scalpels and Knives 194 Scissors 196 Bone Cutting Forceps 198 Rib Shears 199 Dissecting Forceps 200 Needle Holder 200 Forceps 201 Clamps 201 Raspatory 201 Saws 202 Gouges 203 Chisels 203 Mallets 204 Probes 204 Retractor 204 Needles 204 Scalpel Blade Remover 204 To order please call +44 (0)1702 602050 or email [email protected] 19312 Scalpels and Knives Baron Scalpel Handle Solid Forged Scalpel 130mm long Stainless steel 178mm long Post Mortem/Autopsy Post Code Description Code Description SC-PM/94 Blade length 70mm SC-PM/003 No 3 SC-PM/004 No 4 Catlin Knife Scalpel Handle Solid forged stainless steel 127mm long Code Description SC-PM/007 No 3 SC-PM/008 No 4 Code Description SC-PM/008a No 4 L SC-PM/011 Blade length 152mm SC-PM/001a No 7 Solid Forged Scalpel Cartilage Knife Solid forged stainless steel Stainless steel 140mm long Code Description Code Description SC-PM/012 Blade length 133mm SC-PM/91 Blade length 25mm SC-PM/013 Blade length 101mm Solid Forged Scalpel Resection Knife Stainless steel Solid forged stainless steel 160mm long Code Description SC-PM/92 Blade length 40mm Code Description SC-PM/017 Blade length 76mm Solid Forged Scalpel Stainless steel Pelvic Organ Knife 165mm long Stainless steel, curved, double edged Code Description Code SC-PM/93 Blade length 50mm SC-PM/020 194 Need advice? Our friendly team of experts will be happy to assist you Scalpels and Knives Slicing Knife For brain or organ, solid forged stainless steel, 22mm blade Post Mortem/Autopsy Post Code Description -

Practice Guidelines for Central Venous Access 2020 an Updated Report by the American Society of Anesthesiologists Task Force on Central Venous Access*

Embargoed for release until approved by ASA House of Delegates. No part of this document may be released, distributed or reprinted until approved. Any unauthorized copying, reproduction, appropriation or communication of the contents of this document without the express written consent of the American Society of Anesthesiologists is subject to civil and criminal prosecution to the fullest extent possible, including punitive damages. Practice Guidelines for Central Venous Access 2020 An Updated Report by the American Society of Anesthesiologists Task Force on Central Venous Access* 1 PRACTICE Guidelines are systematically developed recommendations that assist the practitioner and patient 2 in making decisions about health care. These recommendations may be adopted, modified, or rejected according 3 to clinical needs and constraints, and are not intended to replace local institutional policies. In addition, Practice 4 Guidelines developed by the American Society of Anesthesiologists (ASA) are not intended as standards or 5 absolute requirements, and their use cannot guarantee any specific outcome. Practice Guidelines are subject to 6 revision as warranted by the evolution of medical knowledge, technology, and practice. They provide basic 7 recommendations that are supported by a synthesis and analysis of the current literature, expert and practitioner 8 opinion, open forum commentary, and clinical feasibility data. 9 This document updates the “Practice Guidelines for Central Venous Access: A Report by the American 10 Society of Anesthesiologists Task Force on Central Venous Access,” adopted by the ASA in 2011 and published 11 in 2012.1 12 Methodology 13 Definition of Central Venous Access 14 For these Guidelines, central venous access is defined as placement of a catheter such that the catheter is 15 inserted into a venous great vessel. -

Catalogues, Internet, Exhibi Tions & Personal Visits to Different Countries of the World

General Surgical Instruments About us: A team of professional experts joined hands to form MAST PAI< SURGICAL CORPORATION with the sole aim to export high Quality surgical Instruments, Specialist in Needle Holder Forceps with Tungsten carbide. Our products were advertised throughout the world by the help of catalogues, Internet, Exhibi tions & personal visits to different countries of the world. These efforts bore fruit and we managed to establish our credibility and began exporting our products. MAST PAI< SURGICAL CORPORATION achieved tremendous success by virtue of constant ded icated efforts, devotion to duty and maintenance of quality control. This quality management system was properly implemented and is being successfully executed at all production stages, which indeed a result of constant professional and vigorous team effort undertaken by MAST PAI< SURGICAL CORPORATION most responsible, professional and dedicated staff members. Its always been our endeavor to maintain a high standard of production, quality control and customer satisfaction. We finally offer our sincere regard and gratitude to all our valued clients for patronizing MAST PAI< SURGICAL CORPORATION and helping us to achieve our goals. Our Mission Establish a global presesnce as a leading designer and manufacturer of high quality handled surgical instruments in the dental and medical surgical fields. Our goal will be achieved through the offering of excellent products and services: and by our commitment of exceed customer expectations. High achievement always takes -

Overview of Gynecologic Oncology

Overview of Gynecologic Oncology “The Blue Book” R. Kevin Reynolds, MD 11th Edition, Revised February 2010 www.med.umich.edu/obgyn/gynonc Gyn Oncology.......................................................................734-764-9106 Cancer Center Answer Line ...............................................800-865-1125 Contents Gyn Tumors Page Breast Cancer ......................................................................... 1 Cervical Cancer 6 Endometrial Cancer................................................. 17 Gestational Trophoblastic Neoplasia 24 Ovarian Cancer ....................................................... 29 Sarcomas 44 Vaginal Cancer........................................................ 51 Vulvar Cancer 53 Associated Treatment Modalities Nutrition, Fluid and Electrolytes 66 Radiation Therapy ................................................... 71 Chemotherapy 75 Perioperative Management ..................................... 94 Tools and Equipment for the Art of Surgery 108 Appendix Out-of-Date Staging Rules .................................... 123 GOG Toxicity Criteria 125 Performance Status............................................... 129 Web Resources 130 Special thanks to William Burke, MD, and to Catherine Christen, PharmD Favorite Quotes "Statistics are no substitute for judgment." Henry Clay "A leading authority is anyone who has guessed right more than once." Frank A. Clark "Well done is better than well said." Ben Franklin "Trust me. I'm a doctor" Donald H. Chamberlain, MD "To err is human; to repeat the