A Narrative Review of the History of Skin Grafting in Burn Care

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Transplantation and Hepatic Pathology University of Pittsburgh Medical Center November, 2007

Resident Handbook Division of Transplantation and Hepatic Pathology University of Pittsburgh Medical Center November, 2007 For private use of residents only- not for public distribution Table of Contents Anatomic Transplantation Pathology Rotation Clinical Responsibilities of the Division ........................................................3 Categorizations of Specimens and Structure of Signout.................................3 Resident Responsibilities................................................................................4 Learning Resources.........................................................................................4 Transplantation Pathology on the World-Wide Web......................................4 Weekly Schedule ............................................................................................6 Staff Locations and Telephone Numbers........................................................7 Background Articles Landmarks in Transplantation ........................................................................8 Trends in Organ Donation and Transplantation US 1996-2005.....................18 Perspectives in Organ Preservation………....................................................26 Transplant Tolerance- Editorial……………………………………….…….36 Kidney Grading Systems Banff 2005 Update……………………….....................................................42 Banff 97 Components (I t v g etc.) ................................................................44 Readings Banff 05 Meeting Report………………………………………...................47 -

Absorbable Surgical Gut Suture

Food and Drug Administration, HHS § 878.4840 § 878.4800 Manual surgical instrument in subpart E of part 807 of this chapter, for general use. subject to the limitations in § 878.9. (a) Identification. A manual surgical [53 FR 23872, June 24, 1988, as amended at 61 instrument for general use is a non- FR 1123, Jan. 16, 1996; 66 FR 38803, July 25, powered, hand-held, or hand-manipu- 2001] lated device, either reusable or dispos- able, intended to be used in various § 878.4820 Surgical instrument motors general surgical procedures. The device and accessories/attachments. includes the applicator, clip applier, bi- (a) Identification. Surgical instrument opsy brush, manual dermabrasion motors and accessories are AC-pow- brush, scrub brush, cannula, ligature ered, battery-powered, or air-powered carrier, chisel, clamp, contractor, cu- devices intended for use during surgical rette, cutter, dissector, elevator, skin procedures to provide power to operate graft expander, file, forceps, gouge, in- various accessories or attachments to strument guide, needle guide, hammer, cut hard tissue or bone and soft tissue. hemostat, amputation hook, ligature Accessories or attachments may in- passing and knot-tying instrument, clude a bur, chisel (osteotome), knife, blood lancet, mallet, disposable dermabrasion brush, dermatome, drill or reusable aspiration and injection bit, hammerhead, pin driver, and saw needle, disposable or reusable suturing needle, osteotome, pliers, rasp, re- blade. tainer, retractor, saw, scalpel blade, (b) Classification. Class I (general con- scalpel handle, one-piece scalpel, snare, trols). The device is exempt from the spatula, stapler, disposable or reusable premarket notification procedures in stripper, stylet, suturing apparatus for subpart E of part 807 of this chapter the stomach and intestine, measuring subject to § 878.9. -

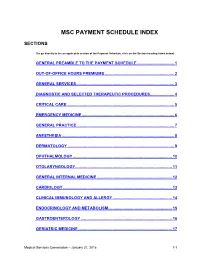

Msc Payment Schedule Index

MSC PAYMENT SCHEDULE INDEX SECTIONS (To go directly to the an applicable section of the Payment Schedule, click on the Section heading listed below) GENERAL PREAMBLE TO THE PAYMENT SCHEDULE .................................. 1 2. OUT-OF-OFFICE HOURS PREMIUMS ............................................................... 2 3. GENERAL SERVICES ......................................................................................... 3 4. DIAGNOSTIC AND SELECTED THERAPEUTIC PROCEDURES ...................... 4 5. CRITICAL CARE .................................................................................................. 5 6. EMERGENCY MEDICINE .................................................................................... 6 7. GENERAL PRACTICE ......................................................................................... 7 8. ANESTHESIA ...................................................................................................... 8 9. DERMATOLOGY ................................................................................................. 9 10. OPHTHALMOLOGY .......................................................................................... 10 11. OTOLARYNGOLOGY ........................................................................................ 11 12. GENERAL INTERNAL MEDICINE .................................................................... 12 13. CARDIOLOGY ................................................................................................... 13 14. CLINICAL IMMUNOLOGY AND ALLERGY -

Ultra Pure Collagen Regenerative Medicine

ENG Ultra pure collagen Regenerative medicine Because we are committed to limiting uncertainty, Specifications Integra continues to develop new products in regenerative technology. • An established product line with proven results. • Outstanding safety profile. • Integra LifeSciences has leveraged over 30 years of science and innovation in the development of • Implanted in over 900 000 patients. collagen technology. • Integra LifeSciences’ extensive collagen purification process, advanced bio-engineering proficiency, and manufacturing experience add value to our products designed for protection, regeneration and repair of human tissue in various clinical applications. • Ultra Pure Collagen™ is the base material of implants used successfully in over 10 million procedures worldwide. • Ultra Pure Collagen™ has been used in general surgery, burn surgery, neurosurgery, plastic and reconstructive surgery, peripheral nerve/tendon surgery & orthopedic surgery. Products for sale in Europe, Middle-East and Africa only Ultra pure collagen Regenerative medicine How was Integra LifeSciences’ Collagen Matrix Created? For over thirty years, Integra LifeSciences has been a leader in developing and manufacturing high quality collagen implants. In the early 1970’s, John F. Burke, MD, chief of Trauma Services at Massachusetts General Hospital and Shriners Burns Institute, identified the need to improve skin restoration of severely burned patients. While patient related donor skin was an option, immunorejection was a critical issue. Dr. Burke theorized that an artificial means to cover the skin might offer positive results without the potential for donor skin rejection. Dr. Burke collaborated with Dr. Ioannas Yannas, a professor What Makes Integra LifeSciences’ Collagen at MIT with a specialization in material sciences and Unique? physical chemistry, to develop a biocompatible product to improve wound healing. -

Skin Grafts in Cutaneous Oncology* Enxertia De Pele Em Oncologia

RevABDV81N5.qxd 07.11.06 17:07 Page 465 465 Artigo de Revisão Enxertia de pele em oncologia cutânea* Skin grafts in cutaneous oncology* José Anselmo Lofêgo Filho1 Paula Dadalti2 Diogo Cotrim de Souza3 Paulo Roberto Cotrim de Souza4 Marcos Aurélio Leiros da Silva5 Cristina Maeda Takiya6 Resumo: Em oncologia cutânea depara-se freqüentemente com situações em que a confec- ção de um enxerto é uma boa alternativa para o fechamento do defeito cirúrgico. Conhecer aspectos referentes à integração e contração dos enxertos é fundamental para que os cirur- giões dermatológicos procedam de maneira a não contrariar princípios básicos do trans- plante de pele. Os autores fazem uma revisão da classificação e fisiologia dos enxertos de pele, acrescendo considerações cirúrgicas determinantes para o sucesso do procedimento. Palavras-chave: Neoplasias cutâneas; Transplante de pele; Transplante homólogo Abstract: In cutaneous oncology, there are many situations in which skin grafts could be a good alternative for closing surgical defect. Dermatological surgeons should have enough knowledge about graft integration and contraction in order to not contradict the basic prin- ciples of skin transplantation. The authors review skin graft classification and physiology and make some surgical considerations on successful procedures. Keywords: Skin neoplasms; Skin transplantation; Transplantation, homologous INTRODUÇÃO Enxerto é parte de um tecido vivo transplanta- tológica. São simples quando apresentam um único do de um lugar para outro no mesmo organismo ou tipo de tecido e compostos quando constituídos de em organismos distintos.1 Contudo, a utilização da dois ou mais tipos de tecidos. Em oncologia cutânea, terminologia enxerto para designar uma modalidade um enxerto composto é usado quando o defeito cirúrgica, apesar de errônea, tornou-se coloquial. -

Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery

ORAL AND MAXILLOFACIAL SURGERY 3rd EDITION 2/2012 US Chapter Pages 1 BASIC SETS OMFS-SET 1-36 TELESCOPES AND INSTRUMENTS FOR FRAKT 37-54 2 ENDOSCOPIC FRACTURE TREATMENT TELESCOPES AND INSTRUMENTS FOR TMJ 55-60 3 ARTHROSCOPY OF TEMPOROMANDIBULAR JOINT TELESCOPES AND INSTRUMENTS FOR DENT 61-80 4 MAXILLARY ENDOSCOPY TELESCOPES AND INSTRUMENTS DENT-K 81-120 5 FOR DENTAL SURGERY TELESCOPES AND INSTRUMENTS SIAL 121-134 6 FOR SIALENDOSCOPY 7 FLEXIBLE ENDOSCOPES FL-E 135-142 8 HOSPITAL SUPPLIES HS 143-240 9 INSTRUMENTS FOR RHINOLOGY AND RHINOPLASTY N 241-298 10 BIPOLAR AND UNIPOLAR COAGULATION COA 299-312 11 HEADMIRRORS – HEADLIGHTS OMFS-J 313-324 12 AUTOFLUORESCENCE AF-INTRO, AF 325-342 13 HOLDING SYSTEMS HT 343-356 VISUALIZATION SYSTEMS OMFS-MICRO, OMFS-VITOM 357-378 14 FOR MICROSURGERY OMFS-UNITS-INTRO, UNITS AND ACCESSORIES U 1-54 15 OMFS-UNITS COMPONENTS OMFS-SP SP 1-58 16 SPARE PARTS KARL STORZ OR1 NEO™, TELEPRESENCE 17 HYGIENE, ENDOPROTECT1 ORAL AND MAXILLOFACIAL SURGERY 3rd EDITION 2/2012 US Important information for U.S. customers Note: Certain devices and references made herein to specific indications of use may have not received clearance or ap- proval by the United States Food and Drug Administration. Practitioners in the United States should first consult with their local KARL STORZ representative in order to ascertain product availability and specific labeling claims. Federal (USA) law restricts certain devices referenced herein to sale, distribution, and use by, or on the order of a physician, dentist, veterinarian, or other practitioner licensed by the law of the State in which she/he practices to use or order the use of the device. -

AMRITA HOSPITALS AMRITA AMRITA HOSPITALS HOSPITALS Kochi * Faridabad (Delhi NCR) Kochi * Faridabad (Delhi NCR)

AMRITA HOSPITALS HOSPITALS AMRITA AMRITA AMRITA HOSPITALS HOSPITALS Kochi * Faridabad (Delhi NCR) Kochi * Faridabad (Delhi NCR) A Comprehensive A Comprehensive Overview Overview A Comprehensive Overview AMRITA INSTITUTE OF MEDICAL SCIENCES AIMS Ponekkara P.O. Kochi, Kerala, India 682 041 Phone: (91) 484-2801234 Fax: (91) 484-2802020 email: [email protected] website: www.amritahospitals.org Copyright@2018 AMRITA HOSPITALS Kochi * Faridabad (Delhi-NCR) A COMPREHENSIVE OVERVIEW A Comprehensive Overview Copyright © 2018 by Amrita Institute of Medical Sciences All rights reserved. No portion of this book, except for brief review, may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means —electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise without permission of the publisher. Published by: Amrita Vishwa Vidyapeetham Amrita Institute of Medical Sciences AIMS Ponekkara P.O. Kochi, Kerala 682041 India Phone: (91) 484-2801234 Fax: (91) 484-2802020 email: [email protected] website: www.amritahospitals.org June 2018 2018 ISBN 1-879410-38-9 Amrita Institute of Medical Sciences and Research Center Kochi, Kerala INDIA AMRITA HOSPITALS KOCHI * FARIDABAD (DELHI-NCR) A COMPREHENSIVE OVERVIEW 2018 Amrita Institute of Medical Sciences and Research Center Kochi, Kerala INDIA CONTENTS Mission Statement ......................................... 04 Message From The Director ......................... 05 Our Founder and Inspiration Sri Mata Amritanandamayi Devi .................. 06 Awards and Accreditations ......................... -

Hesitant Steps from the Artificial Skin to Organ Regeneration

Hesitant steps from the artificial skin to organ regeneration The MIT Faculty has made this article openly available. Please share how this access benefits you. Your story matters. Citation Yannas, Ioannis V. “Hesitant Steps from the Artificial Skin to Organ Regeneration.” Regenerative Biomaterials (June 26, 2018). As Published http://dx.doi.org/10.1093/RB/RBY012 Publisher Oxford University Press (OUP) Version Final published version Citable link http://hdl.handle.net/1721.1/120040 Terms of Use Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International license Detailed Terms https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/ Regenerative Biomaterials, 2018, 189–195 doi: 10.1093/rb/rby012 Advance Access Publication Date: 26 June 2018 Review Hesitant steps from the artificial skin to organ regeneration Ioannis V. Yannas* Downloaded from https://academic.oup.com/rb/article-abstract/5/4/189/5045640 by MIT Libraries user on 14 January 2019 Department of Mechanical Engineering, Massachusetts Institute of Technology, Cambridge, MA 02139, USA *Correspondence address. Department of Mechanical Engineering, Massachusetts Institute of Technology, Room 3-332, 77 Mass. Ave., Cambridge, MA 02139-4307, USA. E-mail: [email protected] Received 7 May 2018; accepted on 10 May 2018 Abstract This is a historical account of the steps, both serendipitous and rational, that led my group of stu- dents and colleagues at MIT and Harvard Medical School to discover induced organ regeneration. Our research led to methods for growing back in adult mammals three heavily injured organs, skin, peripheral nerves and the conjunctiva. We conclude that regeneration in adults is induced by a modification of normal wound healing. -

CPT Code Description Charge Amount 83498 17-Alpha

CPT Code Description Charge Amount 83498 17-alpha-Hydroxyprogester 308.41 83497 5-HIAA, SO 125.99 83516 A MYELOPEROX (MPO) AB QL 74.1 86021 AB ID LEUKOCYTE AB/SO 610.25 86022 AB ID, PLATELET ABS;SRA U 1318 86720 AB LEPTOSPIRA/SO 166.12 86850 AB SCREEN (IDC) 207.83 86850 AB SCREEN RBC EA SRM TECH 195.25 86793 AB, YERSINIA/SO 149 74018 ABDOMEN 1 VIEW 348.75 74018 ABDOMEN 1 VIEW PORTABLE 321.36 74022 ABDOMEN ACUTE COMP WSGL V 398.36 74019 ABDOMEN COMPLETE 398.36 74018 ABDOMEN SGL ANTEROPOSTERI 475.8 49083 ABDOMINAL PARACENTESIS W/ 1216.89 86870 ABID,WNJ 294.85 ABLATOR APOLLORF XL90 ASP 877.8 86900 ABO BLOOD TYPE 370 86900 ABO,BBSO 176.5 73050 AC JOINTS W/WO WEIGHTS BI 297.94 ACCUGRID RADIOGRAPH BREAS 121.36 82164 ACE, CSF SO 144.38 83519 ACHR BIND AB QT,RIA/SO MA 258 83519 ACHR BIND QNT MGP/SO 181.37 83519 ACHR BLOC QNT MGP/SO 181.37 83519 ACHR GANGL NEUR AB,RIA/SO 258 83519 ACHR MOD QNT MGP/SO 201.16 87116 ACID FAST CULTURE SO 227.33 83519 ACR BLOCKING QNT SO 181.37 83519 ACR RECEPTOR QNT SO 108.61 82024 ACTH,SO 459.3 86602 ACTINOMYCES AB/SO 64 85347 ACTIVATED CLOTTING TIME 126.93 85307 Activated Protein C Resis 216.04 97535GO ACTIVITY DAILY LIVING 15 265.91 78278 ACUTE GI BLOOD LOSS IMAGI 1326.15 82017 ACYLCARNITINES; QUANT, EA 574 85397 ADAMSTS 13 ACTIVITY/SO 796.62 ADAPTER CATH LUER 8.69 ADAPTER CONFIDENCE CEMENT 743.66 ADAPTER DLP PERFUS Y W/6 47.54 ADAPTER FIBEROPTIC SWIVEL 73.16 ADAPTER LUER LOC SHORT 3/ 2.2 ADAPTER LUER TO COLDER 15.29 ADAPTER MALE-MALE 4.57 C1776 ADAPTER PFC SIGMA FEMORAL 8474.76 ADAPTER PLUG MALE CLAVE 5.02 ADAPTER PRODIGY EXTENSION 2340 ADAPTER UROSTOMY DRAIN TU 9.09 ADAPTER VERSO AIRWAY ADUL 33.51 82952 ADDL GLUCOSE > 3 SPEC 136.24 87260 ADENOV/ RSPFAC / SO 141.75 ADHESIVE DEMABOND .07 PEN 193.48 ADHESIVE DEMABOND .07 PEN 193.48 ADHESIVE DERMABOND PEN 0. -

Hospitals for War-Wounded

hospitals_war_cover_april2003 9.6.2005 13:47 Page 1 ICRC HOSPITALS FOR WAR-WOUNDED HOSPITALS FORHOSPITALS WAR-WOUNDED This book is intended for anyone who is faced A practical guide for setting up with the task of setting up or running a hospital and running a surgical hospital which admits war-wounded. It is a practical guide in an area of armed conflict based on the experience of four nurses who have managed independent hospitals set up by the International Committee of the Red Cross. It addresses specific problems associated with setting up a hospital in a difficult and potentially dangerous environment. It provides a framework for the administration of such a hospital. It also describes a system for managing the patients from admission to discharge and includes guidelines on how to manage an influx of wounded. These guidelines represent a realistic and achievable standard of care whatever the circumstances. A practical guide 0714/002 05/2005 1000 HOSPITALS FOR WAR-WOUNDED International Committee of the Red Cross 19 Avenue de la Paix 1202 Geneva, Switzerland T +41 22 734 6001 F +41 22 733 2057 E-mail: [email protected] www.icrc.org # ICRC, April 2005, revised and updated edition This book is dedicated to the memory of Jo´n Karlsson (died in Afghanistan, 22 April 1992) Fernanda Calado Hans Elkerbout Ingebjørg Foss Nancy Malloy Gunnhild Myklebust Sheryl Thayer (died in Chechnya, 17 December 1996) HOSPITALS FOR WAR-WOUNDED A practical guide for setting up and running a surgical hospital in an area of armed conflict Jenny Hayward-Karlsson Sue Jeffery Ann Kerr Holger Schmidt INTERNATIONAL COMMITTEE OF THE RED CROSS ISBN 2-88145-094-6 # International Committee of the Red Cross, Geneva, 1998 WEB address: http://www.icrc.org CONTENTS vii CONTENTS FOREWORD ............................................ -

Skin Resurfacing for the Burned Patient

00. ם NEW DIRECTIONS IN PLASTIC SURGERY, PART II 0094–1298/02 $15.00 SKIN RESURFACING FOR THE BURNED PATIENT Ryan A. Stanton, MD, and David A. Billmire, MD The ultimate goal and eventual reward in factory quality of life and adapt a functional treating severely burned patients is the estab- postburn lifestyle. A rough indicator of indi- lishment of a protective barrier from the out- vidual psychologic rehabilitation is reflected side world. Skin resurfacing for the burned by employment status. Patients who return to patient has made large strides since the mid- work after burn injury have less behavioral twentieth century. Improvements in resuscita- avoidance, higher self esteem, and greater at- tion, management of inhalation injuries, and tention to goals. It has been shown that the other advances in critical care are responsible most significant predictors of return to work for survival rates in burned patients nearly are involvement of the hand, grafting, size of doubling since the 1950s, increasing by al- burn, and age. Patients younger than 45 have most 1% each year.49, 57 Several factors have a higher return to work rate.74 The care of a contributed extensively to the evolution of severely burned patient requires the infra- clinical burn care, including a better under- structure of a dedicated burn center with in- standing of the critical need for adequate terdisciplinary involvement of nursing, coun- fluid resuscitation immediately postburn, seling, group therapy, and occupational and prophylaxis against wound sepsis and its physical therapy. Interventions designed to complications, the importance of adequate aid adjustment, work hardening, and other nutritional support, burn pathophysiology rehabilitative services and marital and family and its inflammatory mediators, management therapy are also important. -

1779-80 Encampment

yr / 1 ■>**' / « * 2 T ¿ v/.- X» '.- .I 3 2 1 !1 3 7 9 ? 7 MORRISTOWN NATIONAL HISTORICAL PARK 1779-80 ENCAMPMENT A STUDY OF MEDICAL SERVICES APRIL 1971 MORRISTOWN NATIONAL HISTORICAL PARK 1779-80 ENCAMPMENT A STUDY OF MEDICAL SERVICES by RICARDO TORRES-REYES OFFICE OF HISTORY AND HISTORIC ARCHITECTURE EASTERN SERVICE CENTER WASHINGTON, D. C. APRIL 1971 UNITED STATES DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR NATIONAL PARK SERVICE Foreword This report on the medical services at Morristown during the winter encampment of 1779-80 was undertaken to restudy and evaluate the subject in the light of the standard practices of the Continental Army Medical Department. One phase of the evaluation is to determine if the existence and location of the present replica of the so-called Tilton Hospital in the Jockey Hollow area can be justified historically. For interpretive purposes, the report reviews the organic structure of the medical or hospital department, identifies and describes health problems and diseases, and outlines the medical resources of the military surgeons to combat incident diseases and preserve the health of the soldiers. Research on the subject was conducted at the Library of Congress, the National Archives, Pennsylvania Historical Society, American Philosophical Society, the Library Company of Philadelphia and the Morristown NHP library. Several persons contributed to the completion of this study. As usual, Superintendent Stephen H. Lewis and Historians Bruce W. Steward and Diana F. Skiles provided splendid cooperation during my stay in the park; Leah S. Burt, Assistant Park Archivist, located Dr. Cochran's "LetterBook" in the Morristown Public Library. In the National Archives, the diligent efforts of Miss Marie Bouhnight, Office of Old Military Records, resulted in locating much-needed hospital returns of Valley Forge, Middlebrook and Morristown.