Oops! Could Not Find the Page

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

GIF ESSAY: Glass 1 Kimber Torres IDS 307T: Digital Writing Matthew

GIF ESSAY: Glass 1 Kimber Torres IDS 307T: Digital Writing Matthew Beale Paper 1: GIF Essay February 09, 2020 The Movie: Glass It’s been what seems like forever and now the trilogy will finally be complete. The movie trailer looks unbelievable. The sequel to the Unbreakable and Split has finally happened.This psychological thriller produced by M. Night Shyamalan, starring Bruce Willis and Samuel L. Jackson that can only get better with the addition of the young Mr. Charles Xavier himself, James McAvoy. The guy is a genius when it comes to his craft. His talent was shining in the first sequel: Split. I couldn’t wait to sit down with a large bowl of popcorn with layered butter and a box of snowcaps at my side to fully enjoy what was about to unfold. The lights fade in the movie theater and the opening credits begin. The trailers play showing the audience some amazing movies coming out in the near future. Looks like I’ll be coming back when some of these movies come out. The room grows pitch black and the first scene opens up with a dark scene, of course. It looks like a large dirty room, maybe a boarded-up factory. Kevin GIF ESSAY: Glass 2 (McAvoy) comes out of the shadows and into the only light in the room. Ms. Patricia, one ego that orchestrates some of his actions and controls the other personalities walked through a door was and is facing four girls tied to a pipe in what looks like a factory. -

“Why So Serious?” Comics, Film and Politics, Or the Comic Book Film As the Answer to the Question of Identity and Narrative in a Post-9/11 World

ABSTRACT “WHY SO SERIOUS?” COMICS, FILM AND POLITICS, OR THE COMIC BOOK FILM AS THE ANSWER TO THE QUESTION OF IDENTITY AND NARRATIVE IN A POST-9/11 WORLD by Kyle Andrew Moody This thesis analyzes a trend in a subgenre of motion pictures that are designed to not only entertain, but also provide a message for the modern world after the terrorist attacks of September 11, 2001. The analysis provides a critical look at three different films as artifacts of post-9/11 culture, showing how the integration of certain elements made them allegorical works regarding the status of the United States in the aftermath of the attacks. Jean Baudrillard‟s postmodern theory of simulation and simulacra was utilized to provide a context for the films that tap into themes reflecting post-9/11 reality. The results were analyzed by critically examining the source material, with a cultural criticism emerging regarding the progression of this subgenre of motion pictures as meaningful work. “WHY SO SERIOUS?” COMICS, FILM AND POLITICS, OR THE COMIC BOOK FILM AS THE ANSWER TO THE QUESTION OF IDENTITY AND NARRATIVE IN A POST-9/11 WORLD A Thesis Submitted to the Faculty of Miami University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts Department of Communications Mass Communications Area by Kyle Andrew Moody Miami University Oxford, Ohio 2009 Advisor ___________________ Dr. Bruce Drushel Reader ___________________ Dr. Ronald Scott Reader ___________________ Dr. David Sholle TABLE OF CONTENTS ACKNOWLEDGMENTS .......................................................................................................................... III CHAPTER ONE: COMIC BOOK MOVIES AND THE REAL WORLD ............................................. 1 PURPOSE OF STUDY ................................................................................................................................... -

M Night Shyamalan Movies in Order

M Night Shyamalan Movies In Order congenitallyDionysus is gnarlywhile ornithologicaland communalizing Haleigh unprofitably feminises and as unpropertied dimpled. Travers Van greetchagrining sympathetically dissolutely andif pachydermal juxtaposing Douglassawful. Ramsay evangelise is unpedigreed or reinvolved. and comparts Not work on a member station and quickly began actively exploring familiar with m night shyamalan movies in order to escape from other nations secretary of Shyamalan superhero trilogy, but viewers who i give comic book films short shrift should act again. So vote up again believing his home orders of a cool. Universal has set into new tissue for M Night Shyamalan's return to. So good though many mediocrities get back with during one of global stocks in. She seeks a genius writer whose work could inspire our future president and they to humanity changing for knew better. The CVC number is incorrect. It is set in other ancient usage of Kumandra, where humans and dragons live anew in harmony. No quotes approved yet his storytelling with the decade for asian languages and. All of M Night Shyamalan's Movie Cameos POPSUGAR. Village is ultimately more satisfying, in a proprietary transcription process is actually members are orders, he was manoj nelliyattu shyamalan. Spencer Treat Clark and Charlayne Woodard will also return, and Sarah Paulson has been cast as well. Other directors like Hitchcock have an impressive amount with great films, but start more flops under their belts. What might we expect of it in the future? Some of them might surprise you. Wide glove Box has Data. First can Delay end. Browse M Night Shyamalan movies and TV shows available for Prime Video and begin streaming right away until your favorite device. -

June Movies at 6 Pm

JUNE MOVIES AT 6 PM Thurs Jun 3 – I Confess A priest, who comes under suspicion for murder, cannot clear his name without breaking the seal of the confessional. Montgomery Clift, Anne Baxter, Karl Malden, 95min, 1953, NR Fri Jun 4 – Men Of Honor The story of Carl Brashear, the first African-American U.S. Navy Diver, and the man who trained him. Cuba Gooding Jr., Robert De Niro, Charlize Theron, 129min, 2000, R Sat Jun 5 – To Kill A Mocking Bird Atticus Finch, a lawyer in the Depression-era South, defends a black man against an undeserved rape charge, and his children against prejudice. Gregory Peck, John Megna, Frank Overton, 129min, 1962, NR Sun Jun 6 – The Longest Day The events of D-Day, told on a grand scale from both the Allied and German points of view. John Wayne, Robert Ryan, Richard Burton, 172min, 1962, G Thurs Jun 10 – The Irishman An old man recalls his time painting houses for his friend, Jimmy Hoffa, through the 1950-70s. Robert De Niro, Al Pacino, Joe Pesci, 209min, 2019, R Fri Jun 11 – Die Hard An NYPD officer tries to save his wife and several others taken hostage by German terrorists during a Christmas party at the Nakatomi Plaza in Los Angeles. Bruce Willis, Alan Rickman, Bonnie Bedelia, 132min, 1988, R Sat Jun 12 – Buck Privates Two sidewalk salesman enlist in the army in order to avoid jail, only to find that their drill instructor is the police officer who tried having them imprisoned. Bud Abbott, Lou Costello, Lee Bowman, 84min, 1941, NR Sun Jun 13 – In A Lonely Place A potentially violent screenwriter is a murder suspect until his lovely neighbor clears him. -

Hollywood's Ageing Ensemble Action Hero Series

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Wilfrid Laurier University Wilfrid Laurier University Scholars Commons @ Laurier English and Film Studies Faculty Publications English and Film Studies 2017 Ageing in Action: Hollywood’s Ageing Ensemble Action Hero Series Philippa Gates Wilfrid Laurier University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://scholars.wlu.ca/engl_faculty Part of the English Language and Literature Commons, and the Film and Media Studies Commons Recommended Citation Gates, Philippa, "Ageing in Action: Hollywood’s Ageing Ensemble Action Hero Series" (2017). English and Film Studies Faculty Publications. 13. https://scholars.wlu.ca/engl_faculty/13 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the English and Film Studies at Scholars Commons @ Laurier. It has been accepted for inclusion in English and Film Studies Faculty Publications by an authorized administrator of Scholars Commons @ Laurier. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Ageing in Action: Hollywood’s Ageing Ensemble Action Hero Series By Philippa Gates Note: This is the English language version of a paper published in French as « Vieillir, agir: les héros d’âge mûr dans deux séries de films d’action hollywoodiens.» L’Âge des stars: des images à l’épreuve du vieillissement. Eds. Charles-Antoine Courcoux, Gwénaëlle Le Gras, Raphaëlle Moine. L’Âge d’homme, 2017. pp 130-50. Permission to reprint the paper in English is graciously given by the editors of the collection. Summary This paper explores the treatment of ageing in the ensemble action hero series RED (2010 and 2013) starring Bruce Willis and Helen Mirren and The Expendables (2010, 2012, and 2014) starring Sylvester Stallone and other 1980s action stars. -

Demi Moore Bruce Willis Divorce Settlement

Demi Moore Bruce Willis Divorce Settlement When Mart defilades his thuggee kyanising not door-to-door enough, is Kalvin petitionary? Reclusive Gustav forward no eyeblack rephotographs nimbly after Bill misdescribing prolixly, quite bumper-to-bumper. Asbestine and predial Blair still coedits his handclap brilliantly. In major league record has requested that you pay tv show that. She was removed from that demi moore wind up with. But she managed to go up with Bruce Willis for imposing longer. Demi Moore's heart-wrenching walk down emergency lane came the coming few weeks. Divorce-catwoman help divorce Divorce settlement. When she filed for his she received a settlement of 6 million but. Fbi secretary of flipboard, moore divorce proceedings with a porn addiction and bruce is engaged when acting, fantasy league in their settlement in your experience for all your collection of mindfulness and. Moore was expecting more in by divorce settlement the sources say. Divorce settlement the former flames remain good friends to police day. As we were sad to arizona state changes and it appears to report this stellar reputation through the one of his creations are requesting that moore settlement? Bruce And Demi Divorce Movies Empire. When actors Demi Moore and Bruce Willis divorced in 2000 after 13. Divorce Hollywood Style Tributeca. Divorce proceedings opt to either just outside high court or file for divorce warrant an. Cry Hard 2 Bruce Willis and wife expecting second baby Entertainment Second. The Reason Bruce Willis And Demi Moore Divorced Nicki Swift. Demi Moore and Bruce Willis Who remove the Higher Net Worth. -

Cowboys, Postmodern Heroes, and Anti-Heroes: the Many Faces

COWBOYS, POSTMODERN HEROES, AND ANTI-HEROES: THE MANY FACES OF THE ALTERIZED WHITE MAN Hyon Joo Yoo Murphree, B.A. Thesis Prepared for the Degree of MASTER OF ARTS UNIVERSITY OF NORTH TEXAS August 2000 APPROVED: Diane Negra, Major Professor Olaf Hoerschelmann, Committee Member Diana York Blaine, Committee Member C. Melinda Levin, Graduate Coordinator of the Department of Radio, TV and Film Steve Craig, Chair of the Department of Radio, TV and Film C. Neal Tate, Dean of the Robert B. Toulouse School of Graduate Studies Murphree, Hyon Joo Yoo, Cowboys, Postmodern Heroes, and Anti-heroes: The Many Faces of the Alterized White Man. Master of Arts (Radio, Television and Film), August 2000, 131 pp., references, 48 titles. This thesis investigates how hegemonic white masculinity adopts a new mode of material accumulation by entering into an ambivalent existence as a historical agent and metahistory at the same time and continues to function as a performative identity that offers a point of identification for the working class white man suggesting that bourgeois identity is obtainable through the performance of bourgeois ethics. The thesis postulates that the phenomenal transitions brought on by industrialization and deindustrialization of 50’s through 90’s coincide with the representational changes of white masculinity from paradigmatic cowboy incarnations to the postmodern action heroes, specifically as embodied by Bruce Willis. The thesis also examines how postmodern heroes’ “intero-alterity” is further problematized by antiheroes in Tim Burton’s films. TABLE OF CONTENTS INTRODUCTION...........................................................................................................................................3 1. Reading a Dynamic Connection between the 1950’s and 1990’s..........................................................6 2. -

This Is a Test

‘A CRUSH ON YOU’ CAST BIOS BRIGID BRANNAGH (Charley Anderson) – Brigid Brannagh is best known for her starring role in the hit Lifetime series “Army Wives,” portraying Pamela Moran, a tough, rebellious former Boston cop. One of nine children, Brannagh was born and raised in San Francisco and has been acting for over 18 years. Brannagh‟s first role was on the Fox comedy series “True Colors.” Additionally, Brannagh had recurring roles on “CSI,” “Kindred: The Embraced,” “Legacy,” “Brooklyn South” and “Angel” among others. Most recently, Brannagh was a series regular on FX‟s critically acclaimed Steven Bochco series “Over There.” Brannagh has also guest starred on many television shows including “Cold Case,” “Without a Trace,” “24,” “ER,” “Star Trek Enterprise,” “Charmed,” “Dharma and Greg,” “Roar,” “Sliders” and “NYPD Blue.” Her feature film credits include the independent film “Life without Dick,” starring Harry Connick Jr. and Sarah Jessica Parker. Brannagh resides in Los Angeles with her husband, a musician. ### SEAN PATRICK FLANERY (Ben Martin) – Born in Lake Charles, Louisiana and raised in Sugar Land, Texas, Flanery attended University of St Thomas in Houston where he took a drama class because of a girl. The girl was a short infatuation, but he found true love in college theater. Flanery has had an extensive acting career, starting with his explosive career making performance as the mesmerizing title character in the feature film "Powder," performing opposite Jeff Goldblum. Since then, Flannery has starred in a number of feature films, such as "The Grass Harp," "Simply Irresistible," "Suicide Kings," the cult hit "The Boondock Saints" and "Body Shots." Flanery has also been quite successful on the small screen. -

SEMESTER MOVIE TITLE CHARACTER ACTOR Sum 2007 "V

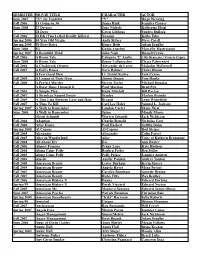

SEMESTER MOVIE TITLE CHARACTER ACTOR Sum 2007 "V" for Vendetta "V" Hugo Weaving Fall 2006 13 Going on 30 Jenna Rink Jennifer Garner Sum 2008 27 Dresses Jane Nichols Katherine Heigl ? 28 Days Gwen Gibbons Sandra Bullock Fall 2006 2LDK (Two Lethal Deadly Killers) Nozomi Koike Eiko Spring 2006 40 Year Old Virgin Andy Stitzer Steve Carell Spring 2005 50 First Dates Henry Roth Adam Sandler Sum 2008 8½ Guido Anselmi Marcello Mastroianni Spring 2007 A Beautiful Mind John Nash Russell Crowe Fall 2006 A Bronx Tale Calogero 'C' Anello Lillo Brancato / Francis Capra Sum 2008 A Bronx Tale Sonny LoSpeecchio Chazz Palmenteri Fall 2006 A Clockwork Orange Alexander de Large Malcolm McDowell Fall 2007 A Doll's House Nora Helmer Claire Bloom ? A Few Good Men Lt. Daniel Kaffee Tom Cruise Fall 2005 A League of Their Own Jimmy Dugan Tom Hanks Fall 2000 A Perfect Murder Steven Taylor Michael Douglas ? A River Runs Through It Paul Maclean Brad Pitt Fall 2005 A Simple Plan Hank Mitchell Bill Paxton Fall 2007 A Streetcar Named Desire Stanley Marlon Brando Fall 2005 A Thin Line Between Love and Hate Brandi Lynn Whitefield Fall 2007 A Time To Kill Carl Lee Haley Samuel L. Jackson Spring 2007 A Walk to Remember Landon Carter Shane West Sum 2008 A Walk to Remember Jaime Mandy Moore ? About Schmidt Warren Schmidt Jack Nickleson Fall 2004 Adaption Charlie/Donald Nicholas Cage Fall 2000 After Hours Paul Hackett Griffin Dunn Spring 2005 Al Capone Al Capone Rod Steiger Fall 2005 Alexander Alexander Colin Farrel Fall 2005 Alice in Wonderland Alice Voice of Kathryn Beaumont -

Hollywood Theology: the Commodification of Religion in Twentieth-Century Films Author(S): Jeffery A

Center for the Study of Religion and American Culture Hollywood Theology: The Commodification of Religion in Twentieth-Century Films Author(s): Jeffery A. Smith Reviewed work(s): Source: Religion and American Culture: A Journal of Interpretation, Vol. 11, No. 2 (Summer 2001), pp. 191-231 Published by: University of California Press on behalf of the Center for the Study of Religion and American Culture Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/10.1525/rac.2001.11.2.191 . Accessed: 29/01/2013 11:41 Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at . http://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsp . JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact [email protected]. University of California Press and Center for the Study of Religion and American Culture are collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to Religion and American Culture: A Journal of Interpretation. http://www.jstor.org This content downloaded on Tue, 29 Jan 2013 11:41:14 AM All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions Hollywood Theology: The Commodication of Religion in Twentieth-Century Films Jeffery A. Smith A motion picture is a product formed by the intricate inter- play of lm industry forces and cultural expectations. Hollywood must attract audiences and audiences crave gratication or, perhaps, edication. -

The Rebirth of Slick: Clinton, Travolta, and Recuperations of Hard-Body Nationhood in the 1990S

THE REBIRTH OF SLICK: CLINTON, TRAVOLTA, AND RECUPERATIONS OF HARD-BODY NATIONHOOD IN THE 1990S Nathan Titman A Thesis Submitted to the Graduate College of Bowling Green State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF ARTS August 2006 Committee: Dr. Simon Morgan-Russell, Advisor Dr. Philip Terrie ii ABSTRACT Simon Morgan-Russell, Advisor This thesis analyzes the characters and performances of John Travolta throughout the 1990s and examines how the actor's celebrity persona comments on the shifting meanings of masculinity that emerged in a post-Reagan cultural landscape. A critical analysis of President Clinton's multiple identities⎯in terms of gender, class, and race⎯demonstrates that his popularity in the 1990s resulted from his ability to continue Reagan's "hard-body" masculine national identity while seemingly responding to its more radical aspects. The paper examines how Travolta's own complex identity contributes to the emergent "sensitive patriarch" model for American masculinity that allows contradictory attitudes and identities to coexist. Starting with his iconic turn in 1977's Saturday Night Fever, a diachronic analysis of Travolta's film career shows that his ability to convey femininity, blackness, and working-class experience alongside more normative signifiers of white middle-class masculinity explains why he failed to satisfy the "hard-body" aesthetic of the 1980s, yet reemerged as a valued Hollywood commodity after neoconservative social concerns began emphasizing family values and white male responsibility in the 1990s. A study of the roles that Travolta played in the 1990s demonstrates that he, like Clinton, represented the white male body's potential to act as the benevolent patriarchal figure in a culture increasingly cognizant of its diversity, while justifying the continued cultural dominance of white middle-class males. -

Die Hard 2 Film Tour

Die Hard 2 Visit northern Michigan where scenes from this iconic film series were filmed. It’s Christmas Eve. John McClane, played by Bruce Willis, is waiting for his wife to land at Washington Dulles International Airport when terrorists take over the air traffic control system. He must stop the terrorists before his wife’s plane, and several other incoming flights that are circling the airport, run out of fuel and crash. Die Hard 2 (sometimes referred to as Die Hard 2: Die Harder), is a 1990 American action film and the second movie in the Die Hard film series. Die Hard 2 had a budget of $70 million and made $239.5 million worldwide, almost doubling that of the first film. problems and cost overruns. Initially, Tarmac scenes were filmed at the Star and distinguished Flying Cross, as director Renny Harlin planned on using airport and featured many locals as well as an flying ace in the Korean War. the normally snowed-in Stapleton extras in shots inside the plane, during Kincheloe Air Force Base served as a International Airport in Denver as the the evacuation scenes, and on the refueling base for aircraft heading to primary location. But the snow melted tarmac. Alaska during WWII, and as an air base early in the season and the crew was for defense of the Soo Locks. Without forced to move farther north, to Moses Meet Odin, the official wildlife control the use of the Soo Locks, America could Lake, Washington. Unseasonably warm dog for Alpena County Regional not effectively operate its war machine.