Brief of the Legislative Parties ______

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Funds List for Fiscal Year Ended June 30, 2020

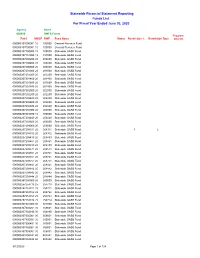

Statewide Financial Statement Reporting Funds List For Fiscal Year Ended June 30, 2020 Agency Name 000000 SWFS Funds Program Fund SWGF SWF Fund Name Status Restriction % Restriction Type Interest 000000101000001 10 100000 General Revenue Fund 000000107000001 10 100000 General Revenue Fund 000000107100000 10 100000 Statewide GASB Fund 000000157151000 15 151000 Statewide GASB Fund 000000207200200 20 200200 Statewide GASB Fund 000000207200400 20 200400 Statewide GASB Fund 000000207200800 20 200800 Statewide GASB Fund 000000207201000 20 201000 Statewide GASB Fund 000000207201200 20 201200 Statewide GASB Fund 000000207201400 20 201400 Statewide GASB Fund 000000207201600 20 201600 Statewide GASB Fund 000000207201800 20 201800 Statewide GASB Fund 000000207202000 20 202000 Statewide GASB Fund 000000207202200 20 202200 Statewide GASB Fund 000000207202400 20 202400 Statewide GASB Fund 000000207202600 20 202600 Statewide GASB Fund 000000207202800 20 202800 Statewide GASB Fund 000000207203000 20 203000 Statewide GASB Fund 000000207203200 10 100000 Statewide GASB Fund 000000207203400 20 203400 Statewide GASB Fund 000000207203600 20 203600 Statewide GASB Fund 000000207208000 20 208000 Statewide GASB Fund 000000207208311 20 208311 Statewide GASB Fund 1 L 000000207208312 20 208312 Statewide GASB Fund 000000207208439 20 208439 Statewide GASB Fund 000000207208461 20 208461 Statewide GASB Fund 000000207208489 20 208489 Statewide GASB Fund 000000207208571 20 208571 Statewide GASB Fund 000000207208701 20 208701 Statewide GASB Fund 000000207208721 20 208721 -

2018 Annual Report

2018 ANNUAL REPORT Fish &Wildlife Foundation SECURING FLORIDA’S NATURAL FUTURE of FloridaT TM MESSAGE FROM THE CHAIRMAN Since our founding in 1994, the Fish & Wildlife and other gamefish populations are healthy. New we’re able to leverage your gifts many times Foundation of Florida has worked to ensure Florida wildlife preserves have been created statewide to over. From gopher tortoises and Osceola turkeys remains a place of unparalleled natural beauty, protect terns, plovers, egrets and other colonial to loggerhead turtles and snook, there are few iconic wildlife, world-famous ecosystems and nesting birds. Since 2010, more than 2.3 million native fish, land animals and habitats that aren’t unbounded outdoor recreational experiences. Florida children have participated in outdoor benefiting from your support. programs, thanks to the 350 private and public We’ve raised and given away more than $32 Please enjoy this annual report and visit our members of the Florida Youth Conservation million over that time, mostly to the Florida Fish website at www.wildlifeflorida.org. For 25 years, Centers Network, which includes FWC’s new and Wildlife Conservation Commission (FWC) for we’ve worked quietly behind the scenes to make Suncoast Youth Conservation Center in Apollo Table of Contents which we are a Citizens Support Organization. good things happen. With your continued help, Beach and the Everglades Youth Conservation But we are also Florida’s largest private funder of we’ll do so much more. WHO WE ARE 3 Camp in Palm Beach County. outdoor education and camps for youth, and we’re WHAT WE DO 9 one of the most important funders of freshwater Our Foundation supports all of this. -

Jim Stevenson Resource Manager of the Year” 2012 Awards Are Announced!

“Jim Stevenson Resource Manager of the Year” 2012 Awards are Announced! Author: Dana C. Bryan, Environmental Policy Coordinator, Florida Park Service Published in the CFEOR Updates Newsletter on May 10, 2013. The spectacular public conservation and recreation lands of Florida are managed by hundreds of skilled staff chiefly from three state agencies: the Florida Forest Service; the Florida Park Service; and the Florida Fish and Wildlife Conservation Commission. The Jim Stevenson Resource Manager of the Year Award is given annually by proclamation of the Governor and Cabinet to recognize a superior land manager from each of these agencies. The award is named for Jim A. Stevenson, who contributed tireless leadership in ecosystem management, prescribed burning, exotic plant control, and springs protection during his long career with DEP’s Florida Park Service and Division of State Lands. The 2012 winners are: Chris Colburn, Forestry Supervisor II, Tallahassee Forestry Center, Florida Forest Service, Department of Agriculture and Consumer Services Chris Colburn works on Lake Talquin State Forest (LTSF), which is comprised of fifteen tracts totaling 19,347 acres in Leon, Gadsden, Liberty, and Wakulla counties. Chris provides all of the resource management planning to meet annual and 10-year management objectives for the Forest, provides all of the resource management oversight, and performs most of the silviculture and restoration fieldwork. In addition, Chris has filled in as the State Lands Forester on Wakulla State Forest and has provided technical support to both Wakulla and Tate’s Hell state forests. These are examples of his desire to provide quality management on all public lands. -

Ross Prairie State Forest Te Florida Scrub Jay Makes Ross Prairie State Forest Its Home

STATE FOREST SPOTLIGHT Tings to Know When Visiting Florida Forest Service Florida Scrub Jay Ross Prairie State Forest Te Florida Scrub Jay makes Ross Prairie State Forest its home. Tis bird was federally listed as a threatened species in 1987 primarily because of habitat loss, fragmentation and degradation. Florida Scrub Jays are picky about habitat, restricted to thickets of oak • Te Florida Park Service’s trailhead and Ross Prairie scrub 3 to 10 feet in height with areas of bare sand campground gates close at 7 P.M. during interspersed. Te habitat needs to be dry and well daylight savings time. State Forest drained. Unfortunately for the Scrub Jay, this same habitat is desirable for urban development because of the well-drained soils. • Pets are welcome but must remain on a leash. Florida Scrub Jays are ofen confused with the more common Blue Jay because they are similar in size. • Do not create new trails. However, Scrub Jays have no crest, are much duller in overall color, have no bold black markings, and lack white-tipped wings and tail feathers. Te most common • All horses must have proof of current negative Scrub Jay vocalization is a loud scratchy weep. Te Coggins test results when on state lands. principal plant food for the Scrub Jay is the acorn. Te majority of acorns gathered, up to 6,000 per year, are hidden in the sand for future meals. • Take all garbage with you when you leave the forest. Containers are not provided. Love the state forests? So do we! • For primitive camping information visit FloridaForestService.ReserveAmerica.com. -

Florida State and Private Forestry Fact Sheet 2021

Information last updated: 1/29/2021 4:48 PM Report prepared: 9/24/2021 9:30 PM State and Private Forestry Fact Sheet Florida 2021 Investment in State's Cooperative Programs Program FY 2020 Final Community Forestry and Open Space $0 Cooperative Lands - Forest Health Management $687,577 Forest Legacy $2,943,000 Forest Stewardship $160,717 Landscape Scale Restoration $688,000 State Fire Assistance $1,506,726 Urban and Community Forestry $860,340 Volunteer Fire Assistance $424,145 Total $7,270,505 NOTE: This funding is for all entities within the state, not just the State Forester's office. Program Goals • Cooperative programs are administered and implemented through a partnership between the Florida Forest Service (FFS), the USDA Forest Service and many other private and government entities. These programs promote the health and productivity of forestlands and rural economies. Programs emphasize forest sustainability and the production of commodity and amenity values such as wildlife, water quality, and environmental services. • The overarching goal is to maintain and improve the health of urban and rural forests and related economies as well as to protect the forests and citizens of the state. These programs maximize cost effectiveness through the use of partnerships in program delivery, increase forestland value and sustainability, and do so in a voluntary and non-regulatory manner. Key Issues • Florida continues to recover from the unprecedented timber damage caused by Hurricane Michael in October 2018. Due to the severity of damage, FFS crews provided immediate response and are still providing hurricane recovery operations. Over 2.8 million acres of forest were impacted, equating to 1.29 billion dollars in damaged resources and impacting approximately 16,000 private forest landowners. -

Outdoor Recreation in Florida — 2008

State of Florida DEPARTMENT OF ENVIRONMENTAL PROTECTION Michael W. Sole Secretary Bob Ballard Deputy Secretary, Land & Recreation DIVISION OF RECREATION AND PARKS Mike Bullock Director and State Liaison Officer Florida Department of Environmental Protection Division of Recreation and Parks Marjory Stoneman Douglas Building 3900 Commonwealth Boulevard Tallahassee, Florida 32399-3000 The Florida Department of Environmental Protection is an equal opportunity agency, offering all persons the benefits of participating in each of its programs and competing in all areas of employment regardless of race, color, religion, sex, national origin, age, disability or other non-merit factors. OUTDOOR RECREATION IN FLORIDA — 2008 A Comprehensive Program For Meeting Florida’s Outdoor Recreation Needs State of Florida, Department of Environmental Protection Division of Recreation and Parks Tallahassee, Florida Outdoor Recreation in Florida, 2008 Table of Contents PAGE Chapter 1: Introduction and Background.............................................................................. 1-1 Purpose and Scope of the Plan ........................................................................................1-1 Outdoor Recreation - A Legitimate Role for Government................................................1-3 Outdoor Recreation Defined..............................................................................................1-3 Roles in Providing Outdoor Recreation ............................................................................1-4 Need -

John Bethea State Forest Management Plan

TEN-YEAR LAND MANAGEMENT PLAN FOR THE JOHN M. BETHEA STATE FOREST BAKER COUNTY, FLORIDA PREPARED BY FLORIDA DEPARTMENT OF AGRICULTURE AND CONSUMER SERVICES FLORIDA FOREST SERVICE APPROVED ON FEBRUARY 19, 2016 TEN-YEAR LAND MANAGEMENT PLAN JOHN M. BETHEA STATE FOREST TABLE OF CONTENTS Land Management Plan Executive Summary ............................................................................... 1 I. Introduction ................................................................................................................................ 2 A. General Mission and Management Plan Direction ............................................................ 2 B. Past Accomplishments ....................................................................................................... 2 C. Goals/Objectives for the Next Ten Year Period ................................................................. 3 II. Administration Section ............................................................................................................. 8 A. Descriptive Information ..................................................................................................... 8 1. Common Name of Property .......................................................................................... 8 2. Legal Description and Acreage..................................................................................... 8 3. Proximity to Other Public Resource ............................................................................. 9 4. Property Acquisition -

Orv Final Text 8/15

OUT OF CONTROL THE IMPACTS OF OFF-ROAD VEHICLES AND ROADS ON WILDLIFE AND HABIT AT IN FLORIDA’S NATIONAL FORESTS Defenders of Wildlife August 2002 Acknowledgments Linda Duever of Conway Conservation, Inc. compiled and prepared the information for this report based on extensive research. Busy Shires assisted with information gathering and processing tasks. Several Defenders of Wildlife staff mem- bers worked on producing the final report: Christine Small supervised the project, coordinated field surveys of impacts on each forest and contributed to the writing and editing; Laura Watchman and Laurie Macdonald provided insight, and guidance; Kate Davies edited the report; Mary Selden and Lisa Hummon proofread and worked on the bibliogra- phy. Heather Nicholson and Chapman Stewart provided assistance with the appended species vulnerability tables. Cissy Russell designed the report and laid out the pages. Cover photos by Corbis Corporation/Lester Lefkowitz (ATV) and Marcie Clutter (background Ocala scene). About Defenders of Wildlife Defenders of Wildlife is a leading nonprofit conservation organization recognized as one of the nation’s most progressive advocates for wildlife and its habitat. Defenders uses education, litigation, research and pro- motion of conservation policies to protect wild animals and plants in their natural communities. Known for its effective leadership on endangered species issues, Defenders also advocates new approaches to wildlife conservation that protect species before they become endangered. Founded in 1947, Defenders of Wildlife is a 501(c)(3) membership organization with more than 450,000 members and supporters. Defenders is head- quartered in Washington, D.C. and has field offices in several states including Florida. -

Timucuan Ecological and Historic Preserve

National Park Service U.S. Department of the Interior Timucuan Ecological and Historic Preserve One-Day Excursions Jacksonville is one of the largest metropolitan areas in the United States. Plan an excursion to explore the city’s urban and natural treasures. Listed below are many parks, museums, and attractions that are within the Timucuan Preserve or near the city of Jacksonville. Please call each site for up-to-date information regarding hours, prices and facilities. Park Areas Fort Caroline National Memorial Talbot Islands State Parks Home of the Timucuan Preserve Visitor Center, These two beautiful park areas offer nature this park memorializes the site of a 16th-century trails, campsites, picnic areas and lots of beach. French colony – the first European settlement in Open daily 8 am to sunset. Admission fee the area. Open daily 9 am to 5 pm, closed charged. Located off Hwy A1A, approx. 3 miles Thanksgiving, New Years Day, Christmas Day. north of the St. Johns River ferry. (904) 251 Free admission. 12713 Ft. Caroline Rd. (904) 2320, 641-7155, www.nps.gov/timu www.floridastateparks.org/littletalbotisland Fort Clinch State Park Theodore Roosevelt Area This restored Civil War fort from the 1840s is This 600-acre natural area within the surrounded by beaches and nature trails. Park Timucuan Preserve has over 5 miles of hiking offers fishing, campsites and picnic grounds. trails winding through one of North Florida’s Open daily 8 am to sundown; Fort open daily 9 most pristine areas. Summer hours: 6 am to 8 am to 5 pm. Located off Hwy A1A in Fernandina pm; Winter hours: 6 am to 6 pm. -

11-15-12 LCJ Sec A.Indd

Around Levy County Be in a Christmas CHS Thanksgiving Food Th e Levy County Journal offi ces Go Back in Time Parade or Pageant Donations will be closed Wednesday, See page 8B Clean up the Suwannee See page Levy Life 1B Th ursday and Friday Nov. 21, 22 and 23, 2012. See Levy Life 1B Need a Pie for the Holidays? See page 6A Your Locally-Owned County Paper of Record since 1923 VOL. 89, NO. 19 THURSDAY, NOVEMBER 15, 2012 50 CENTS Meth Cookers Busted Wounded Veterans Hunt in Florida Florida Commissioner of by Inglis PD, LC Drug Agriculture Adam H. Putnam and Florida’s agriculture community are Task Force and Citrus honoring the service of our nation’s military by off ering unique hunting opportunities to wounded veterans Tactical Unit on Florida state forests and private Law enforcement’s message – lands during Operation Outdoor Freedom Weekend, November If you’re cooking, we’re coming! 17 through 18. Th e fi rst weekend was Nov. 10 through 11 as part of Operation Outdoor Freedom, a program of the Florida Department of Agriculture and Consumer Services’ Florida Forest Service that provides recreational opportunities to Florida’s wounded veterans. “Th ere is no greater sacrifi ce than to serve our country and I’m proud Suwannee counties hosted by fi ve private landowners, to honor our nation’s veterans through Operation in cooperation with Operation Outdoor Freedom. Outdoor Freedom,” said Commissioner Putnam. “Th is Th e hosts will provide meals and accommodations in hunting season, we’ve partnered with the agriculture addition to the activities. -

Hiking Trails a Guide to Florida’S Top Hiking Trails Florida Hiking Trails

FloridaHiking Trails A Guide to Florida’s Top Hiking Trails Florida Hiking Trails Hiking Florida Blessed with an abundance of sunshine and foliage, Florida presents the perfect destination for hikers to explore and experience the Sunshine State’s natural and historic diversity. In Florida, hiking opens your eyes to the dynamic environmental changes that occur as elevation increases from below sea level to only 345 feet. With more than 80 different natural communities, Florida presents more botanical diversity than any other state on the East Coast, and does so with grace along its thousands of miles of hiking trails. From the tropical hammocks of the Keys to the pine forests of the Panhandle, Florida’s hiking trails provide more to explore, including 10,000 years of cultural history. From short self-guided nature trails to overnight hiking trips along the National Scenic Trail, Florida has it all. You’ll find hiking trails for every season and for every experience. So grab your pack and water bottle, and Hike Florida! How to use this Guide: Each destination listed in the brochure may have multiple types of trails. Each trail mentioned for the destination is color-coded based on the type of trail. Trails marked in blue are gentle strolls on nature trails. Green signifies the opportunity to take a longer hike, of up to 10 miles in a day. Trails marked red are best for an overnight backpacking experience. The destination itself is color- coded to signify the easiest type of hike available at that destination. Parking Picnic Area Restrooms Camping Area Wheelchair Access Cabins Water Fountain Bird Watching Food and/or Bottled Water All times listed are EST (Eastern Standard Time) unless otherwise noted CST (Central Standard Time). -

Message from the Director

January 2015 ISSUE 02 FLForestryOFFICIAL NEWSLETTER OF THE FLORIDA FOREST SERVICE News This Issue Tree Farmer of the Year P.02 Forest Legacy P.03 Wildlife Best Management Practices P.04 The Florida Forest Service Timber Sales on State Forests P.05 is a division of the Florida New State Forest in Alachua County P.06 Department of Agriculture and Trailwarrior Program P.07 Consumer Services and consists Arbor Day and Reforestation P.08 of more than 1,250 dedicated Firewise Communities in Florida employees who manage more P.09 than 1 million acres of public for- Federal Excess Program P.10 Tate’s Hell State Forest estland while protecting 26 million acres of homes, forestland and Message from the Director natural resources from the devas- Another year has come to a • Certified 59 Firewise Communities and completed tating effects of wildfire close and I truly hope that 38 county-wide Community Wildfire Protection all of our readers have had Plans. In addition to managing more the opportunity to enjoy some than 1 million acres of State quality time with family and • Hosted 62 Operation Outdoor Freedom Events, Forests for multiple public uses loved ones. This past year, which provided outdoor recreational opportunities including timber, recreation and the Florida Forest Service has for 400 of Florida’s wounded veterans. wildlife habitat, the Florida Forest Jim Karels, State Forester achieved many accomplish- Service also provides services to ments for Florida’s citizens. I remain as proud as • Assisted more than 470 landowners, providing landowners throughout the state, ever to be the director of this first-class forestry and more than $1.7 million in federal funding to help including technical information maintain healthy, productive forests on more than and grant program administration.