Tate's Hell State Forest Management Plan

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Mediterranean Forests Are Extraordinarily Beautiful, a Fascinating an Extraordinary Patrimony of Wealth Whose Conservation Can Be Highly Controversy

THE editerraneanFORESTS mA NEW CONSERVATION STRATEGY 1 3 2 4 5 6 the unveiled a meeting point the mediterranean: amazing plant an unknown millennia forests on the global 200 the terrestrial current a brand new the state of WWF a new approach wealth of the of nature a sea of forests diversity animal world of human the wane in the sub-ecoregions mediterranean tool: the gap mediterranean in action for forest mediterranean and civilisations interaction with mediterranean in the forest cover analysis forests protection forests forests mediterranean 23 46 81012141617 18 19 22 24 7 1 Argania spinosa fruits, Essaouira, Morocco. Credit: WWF/P. Regato 2 Reed-parasol maker, Tunisia. Credit: WWF-Canon/M. Gunther 3 Black-shouldered Kite. Credit: Francisco Márquez 4 Endemic mountain Aquilegia, Corsica. Credit: WWF/P. Regato 5 Sacred ibis. Credit: Alessandro Re 6 Joiner, Kure Mountains, Turkey. Credit: WWF/P. Regato 7 Barbary ape, Morocco. Credit: A. & J. Visage/Panda Photo It is like no other region on Earth. Exotic, diverse, roamed by mythical WWF Mediterranean Programme Office launched its campaign in 1999 creatures, deeply shaped by thousands of years of human intervention, the to protect 10 outstanding forest sites among the 300 identified through cradle of civilisations. a comprehensive study all over the region. When we talk about the Mediterranean region, you could be forgiven for The campaign has produced encouraging results in countries such as Spain, thinking of azure seas and golden beaches, sun and sand, a holidaymaker’s Turkey, Croatia and Lebanon. NATURE AND CULTURE, of forest environments in the region. But in recent times, the balance AN INTIMATE RELATIONSHIP Long periods of considerable forest between nature and humankind has paradise. -

"National List of Vascular Plant Species That Occur in Wetlands: 1996 National Summary."

Intro 1996 National List of Vascular Plant Species That Occur in Wetlands The Fish and Wildlife Service has prepared a National List of Vascular Plant Species That Occur in Wetlands: 1996 National Summary (1996 National List). The 1996 National List is a draft revision of the National List of Plant Species That Occur in Wetlands: 1988 National Summary (Reed 1988) (1988 National List). The 1996 National List is provided to encourage additional public review and comments on the draft regional wetland indicator assignments. The 1996 National List reflects a significant amount of new information that has become available since 1988 on the wetland affinity of vascular plants. This new information has resulted from the extensive use of the 1988 National List in the field by individuals involved in wetland and other resource inventories, wetland identification and delineation, and wetland research. Interim Regional Interagency Review Panel (Regional Panel) changes in indicator status as well as additions and deletions to the 1988 National List were documented in Regional supplements. The National List was originally developed as an appendix to the Classification of Wetlands and Deepwater Habitats of the United States (Cowardin et al.1979) to aid in the consistent application of this classification system for wetlands in the field.. The 1996 National List also was developed to aid in determining the presence of hydrophytic vegetation in the Clean Water Act Section 404 wetland regulatory program and in the implementation of the swampbuster provisions of the Food Security Act. While not required by law or regulation, the Fish and Wildlife Service is making the 1996 National List available for review and comment. -

Global Ecological Forest Classification and Forest Protected Area Gap Analysis

United Nations Environment Programme World Conservation Monitoring Centre Global Ecological Forest Classification and Forest Protected Area Gap Analysis Analyses and recommendations in view of the 10% target for forest protection under the Convention on Biological Diversity (CBD) 2nd revised edition, January 2009 Global Ecological Forest Classification and Forest Protected Area Gap Analysis Analyses and recommendations in view of the 10% target for forest protection under the Convention on Biological Diversity (CBD) Report prepared by: United Nations Environment Programme World Conservation Monitoring Centre (UNEP-WCMC) World Wide Fund for Nature (WWF) Network World Resources Institute (WRI) Institute of Forest and Environmental Policy (IFP) University of Freiburg Freiburg University Press 2nd revised edition, January 2009 The United Nations Environment Programme World Conservation Monitoring Centre (UNEP- WCMC) is the biodiversity assessment and policy implementation arm of the United Nations Environment Programme (UNEP), the world's foremost intergovernmental environmental organization. The Centre has been in operation since 1989, combining scientific research with practical policy advice. UNEP-WCMC provides objective, scientifically rigorous products and services to help decision makers recognize the value of biodiversity and apply this knowledge to all that they do. Its core business is managing data about ecosystems and biodiversity, interpreting and analysing that data to provide assessments and policy analysis, and making the results -

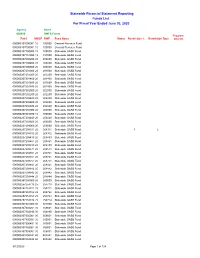

Funds List for Fiscal Year Ended June 30, 2020

Statewide Financial Statement Reporting Funds List For Fiscal Year Ended June 30, 2020 Agency Name 000000 SWFS Funds Program Fund SWGF SWF Fund Name Status Restriction % Restriction Type Interest 000000101000001 10 100000 General Revenue Fund 000000107000001 10 100000 General Revenue Fund 000000107100000 10 100000 Statewide GASB Fund 000000157151000 15 151000 Statewide GASB Fund 000000207200200 20 200200 Statewide GASB Fund 000000207200400 20 200400 Statewide GASB Fund 000000207200800 20 200800 Statewide GASB Fund 000000207201000 20 201000 Statewide GASB Fund 000000207201200 20 201200 Statewide GASB Fund 000000207201400 20 201400 Statewide GASB Fund 000000207201600 20 201600 Statewide GASB Fund 000000207201800 20 201800 Statewide GASB Fund 000000207202000 20 202000 Statewide GASB Fund 000000207202200 20 202200 Statewide GASB Fund 000000207202400 20 202400 Statewide GASB Fund 000000207202600 20 202600 Statewide GASB Fund 000000207202800 20 202800 Statewide GASB Fund 000000207203000 20 203000 Statewide GASB Fund 000000207203200 10 100000 Statewide GASB Fund 000000207203400 20 203400 Statewide GASB Fund 000000207203600 20 203600 Statewide GASB Fund 000000207208000 20 208000 Statewide GASB Fund 000000207208311 20 208311 Statewide GASB Fund 1 L 000000207208312 20 208312 Statewide GASB Fund 000000207208439 20 208439 Statewide GASB Fund 000000207208461 20 208461 Statewide GASB Fund 000000207208489 20 208489 Statewide GASB Fund 000000207208571 20 208571 Statewide GASB Fund 000000207208701 20 208701 Statewide GASB Fund 000000207208721 20 208721 -

2018 Annual Report

2018 ANNUAL REPORT Fish &Wildlife Foundation SECURING FLORIDA’S NATURAL FUTURE of FloridaT TM MESSAGE FROM THE CHAIRMAN Since our founding in 1994, the Fish & Wildlife and other gamefish populations are healthy. New we’re able to leverage your gifts many times Foundation of Florida has worked to ensure Florida wildlife preserves have been created statewide to over. From gopher tortoises and Osceola turkeys remains a place of unparalleled natural beauty, protect terns, plovers, egrets and other colonial to loggerhead turtles and snook, there are few iconic wildlife, world-famous ecosystems and nesting birds. Since 2010, more than 2.3 million native fish, land animals and habitats that aren’t unbounded outdoor recreational experiences. Florida children have participated in outdoor benefiting from your support. programs, thanks to the 350 private and public We’ve raised and given away more than $32 Please enjoy this annual report and visit our members of the Florida Youth Conservation million over that time, mostly to the Florida Fish website at www.wildlifeflorida.org. For 25 years, Centers Network, which includes FWC’s new and Wildlife Conservation Commission (FWC) for we’ve worked quietly behind the scenes to make Suncoast Youth Conservation Center in Apollo Table of Contents which we are a Citizens Support Organization. good things happen. With your continued help, Beach and the Everglades Youth Conservation But we are also Florida’s largest private funder of we’ll do so much more. WHO WE ARE 3 Camp in Palm Beach County. outdoor education and camps for youth, and we’re WHAT WE DO 9 one of the most important funders of freshwater Our Foundation supports all of this. -

Jim Stevenson Resource Manager of the Year” 2012 Awards Are Announced!

“Jim Stevenson Resource Manager of the Year” 2012 Awards are Announced! Author: Dana C. Bryan, Environmental Policy Coordinator, Florida Park Service Published in the CFEOR Updates Newsletter on May 10, 2013. The spectacular public conservation and recreation lands of Florida are managed by hundreds of skilled staff chiefly from three state agencies: the Florida Forest Service; the Florida Park Service; and the Florida Fish and Wildlife Conservation Commission. The Jim Stevenson Resource Manager of the Year Award is given annually by proclamation of the Governor and Cabinet to recognize a superior land manager from each of these agencies. The award is named for Jim A. Stevenson, who contributed tireless leadership in ecosystem management, prescribed burning, exotic plant control, and springs protection during his long career with DEP’s Florida Park Service and Division of State Lands. The 2012 winners are: Chris Colburn, Forestry Supervisor II, Tallahassee Forestry Center, Florida Forest Service, Department of Agriculture and Consumer Services Chris Colburn works on Lake Talquin State Forest (LTSF), which is comprised of fifteen tracts totaling 19,347 acres in Leon, Gadsden, Liberty, and Wakulla counties. Chris provides all of the resource management planning to meet annual and 10-year management objectives for the Forest, provides all of the resource management oversight, and performs most of the silviculture and restoration fieldwork. In addition, Chris has filled in as the State Lands Forester on Wakulla State Forest and has provided technical support to both Wakulla and Tate’s Hell state forests. These are examples of his desire to provide quality management on all public lands. -

National List of Vascular Plant Species That Occur in Wetlands 1996

National List of Vascular Plant Species that Occur in Wetlands: 1996 National Summary Indicator by Region and Subregion Scientific Name/ North North Central South Inter- National Subregion Northeast Southeast Central Plains Plains Plains Southwest mountain Northwest California Alaska Caribbean Hawaii Indicator Range Abies amabilis (Dougl. ex Loud.) Dougl. ex Forbes FACU FACU UPL UPL,FACU Abies balsamea (L.) P. Mill. FAC FACW FAC,FACW Abies concolor (Gord. & Glend.) Lindl. ex Hildebr. NI NI NI NI NI UPL UPL Abies fraseri (Pursh) Poir. FACU FACU FACU Abies grandis (Dougl. ex D. Don) Lindl. FACU-* NI FACU-* Abies lasiocarpa (Hook.) Nutt. NI NI FACU+ FACU- FACU FAC UPL UPL,FAC Abies magnifica A. Murr. NI UPL NI FACU UPL,FACU Abildgaardia ovata (Burm. f.) Kral FACW+ FAC+ FAC+,FACW+ Abutilon theophrasti Medik. UPL FACU- FACU- UPL UPL UPL UPL UPL NI NI UPL,FACU- Acacia choriophylla Benth. FAC* FAC* Acacia farnesiana (L.) Willd. FACU NI NI* NI NI FACU Acacia greggii Gray UPL UPL FACU FACU UPL,FACU Acacia macracantha Humb. & Bonpl. ex Willd. NI FAC FAC Acacia minuta ssp. minuta (M.E. Jones) Beauchamp FACU FACU Acaena exigua Gray OBL OBL Acalypha bisetosa Bertol. ex Spreng. FACW FACW Acalypha virginica L. FACU- FACU- FAC- FACU- FACU- FACU* FACU-,FAC- Acalypha virginica var. rhomboidea (Raf.) Cooperrider FACU- FAC- FACU FACU- FACU- FACU* FACU-,FAC- Acanthocereus tetragonus (L.) Humm. FAC* NI NI FAC* Acanthomintha ilicifolia (Gray) Gray FAC* FAC* Acanthus ebracteatus Vahl OBL OBL Acer circinatum Pursh FAC- FAC NI FAC-,FAC Acer glabrum Torr. FAC FAC FAC FACU FACU* FAC FACU FACU*,FAC Acer grandidentatum Nutt. -

Ross Prairie State Forest Te Florida Scrub Jay Makes Ross Prairie State Forest Its Home

STATE FOREST SPOTLIGHT Tings to Know When Visiting Florida Forest Service Florida Scrub Jay Ross Prairie State Forest Te Florida Scrub Jay makes Ross Prairie State Forest its home. Tis bird was federally listed as a threatened species in 1987 primarily because of habitat loss, fragmentation and degradation. Florida Scrub Jays are picky about habitat, restricted to thickets of oak • Te Florida Park Service’s trailhead and Ross Prairie scrub 3 to 10 feet in height with areas of bare sand campground gates close at 7 P.M. during interspersed. Te habitat needs to be dry and well daylight savings time. State Forest drained. Unfortunately for the Scrub Jay, this same habitat is desirable for urban development because of the well-drained soils. • Pets are welcome but must remain on a leash. Florida Scrub Jays are ofen confused with the more common Blue Jay because they are similar in size. • Do not create new trails. However, Scrub Jays have no crest, are much duller in overall color, have no bold black markings, and lack white-tipped wings and tail feathers. Te most common • All horses must have proof of current negative Scrub Jay vocalization is a loud scratchy weep. Te Coggins test results when on state lands. principal plant food for the Scrub Jay is the acorn. Te majority of acorns gathered, up to 6,000 per year, are hidden in the sand for future meals. • Take all garbage with you when you leave the forest. Containers are not provided. Love the state forests? So do we! • For primitive camping information visit FloridaForestService.ReserveAmerica.com. -

3. Canary Islands and the Laurel Forest 13

The Laurel Forest An Example for Biodiversity Hotspots threatened by Human Impact and Global Change Dissertation 2014 Dissertation submitted to the Combined Faculties for the Natural Sciences and for Mathematics of the Ruperto–Carola–University of Heidelberg, Germany for the degree of Doctor of Natural Sciences presented by Dipl. biol. Anja Betzin born in Kassel, Hessen, Germany Oral examination date: 2 The Laurel Forest An Example for Biodiversity Hotspots threatened by Human Impact and Global Change Referees: Prof. Dr. Marcus A. Koch Prof. Dr. Claudia Erbar 3 Eidesstattliche Erklärung Hiermit erkläre ich, dass ich die vorgelegte Dissertation selbst verfasst und mich dabei keiner anderen als der von mir ausdrücklich bezeichneten Quellen und Hilfen bedient habe. Außerdem erkläre ich hiermit, dass ich an keiner anderen Stelle ein Prüfungsverfahren beantragt bzw. die Dissertation in dieser oder anderer Form bereits anderweitig als Prü- fungsarbeit verwendet oder einer anderen Fakultät als Dissertation vorgelegt habe. Heidelberg, den 23.01.2014 .............................................. Anja Betzin 4 Contents I. Summary 9 1. Abstract 10 2. Zusammenfassung 11 II. Introduction 12 3. Canary Islands and the Laurel Forest 13 4. Aims of this Study 20 5. Model Species: Laurus novocanariensis and Ixanthus viscosus 21 5.1. Laurus ...................................... 21 5.2. Ixanthus ..................................... 23 III. Material and Methods 24 6. Sampling 25 7. Laboratory Procedure 27 7.1. DNA Extraction . 27 7.2. AFLP Procedure . 27 7.3. Scoring . 29 7.4. High Resolution Melting . 30 8. Data Analysis 32 8.1. AFLP and HRM Data Analysis . 32 8.2. Hotspots — Diversity in Geographic Space . 34 8.3. Ecology — Ecological and Bioclimatic Analysis . -

Macbridea Alba

Macbridea alba (White birds-in-a-nest) 5-Year Review: Summary and Evaluation Lathrop Management Area, Bay County. Photos by Vivian Negrón-Ortiz U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service Southeast Region Panama City Field Office Panama City, Florida 5-YEAR REVIEW Macbridea alba (White birds-in-a-nest) I. GENERAL INFORMATION A. Methodology used to complete the review This review was accomplished using information obtained from the plant’s 1994 Recovery Plan, peer reviewed scientific publications, unpublished field survey results, reports of current research projects, unpublished field observations by Service, State and other experienced biologists, and personal communications. These documents are on file at the Panama City Field Office. A Federal Register notice announcing the review and requesting information was published on April 16, 2008 (73 FR 20702). Comments received and suggestions from peer reviewers were evaluated and incorporated as appropriate (see appendix A). No part of this review was contracted to an outside party. This review was completed by the Service’s lead Recovery botanist in the Panama City Field Office, Florida. B. Reviewers Lead Field Office: Dr. Vivian Negrón-Ortiz, Panama City Field Office, 850-769-0552 ext. 231, [email protected] Lead Region: Southeast Region: Kelly Bibb, 404-679-7132 Peer reviewers: Ms. Louise Kirn, District Ecologist Apalachicola National Forest P.O. Box 579, Bristol, FL 32321 Ms. Faye Winters, Field Office Biologist BLM Jackson Field Office 411 Briarwood Drive, Suite 404 Jackson, MS 39206 C. Background 1. FR Notice citation announcing initiation of this review: 73 FR 20702 (April 16, 2008). 1 2. Species status: Unknown (Recovery Data Call 2008); the species status is unknown until all the Element Occurrences1 (EO’s) are revisited. -

Florida State and Private Forestry Fact Sheet 2021

Information last updated: 1/29/2021 4:48 PM Report prepared: 9/24/2021 9:30 PM State and Private Forestry Fact Sheet Florida 2021 Investment in State's Cooperative Programs Program FY 2020 Final Community Forestry and Open Space $0 Cooperative Lands - Forest Health Management $687,577 Forest Legacy $2,943,000 Forest Stewardship $160,717 Landscape Scale Restoration $688,000 State Fire Assistance $1,506,726 Urban and Community Forestry $860,340 Volunteer Fire Assistance $424,145 Total $7,270,505 NOTE: This funding is for all entities within the state, not just the State Forester's office. Program Goals • Cooperative programs are administered and implemented through a partnership between the Florida Forest Service (FFS), the USDA Forest Service and many other private and government entities. These programs promote the health and productivity of forestlands and rural economies. Programs emphasize forest sustainability and the production of commodity and amenity values such as wildlife, water quality, and environmental services. • The overarching goal is to maintain and improve the health of urban and rural forests and related economies as well as to protect the forests and citizens of the state. These programs maximize cost effectiveness through the use of partnerships in program delivery, increase forestland value and sustainability, and do so in a voluntary and non-regulatory manner. Key Issues • Florida continues to recover from the unprecedented timber damage caused by Hurricane Michael in October 2018. Due to the severity of damage, FFS crews provided immediate response and are still providing hurricane recovery operations. Over 2.8 million acres of forest were impacted, equating to 1.29 billion dollars in damaged resources and impacting approximately 16,000 private forest landowners. -

Outdoor Recreation in Florida — 2008

State of Florida DEPARTMENT OF ENVIRONMENTAL PROTECTION Michael W. Sole Secretary Bob Ballard Deputy Secretary, Land & Recreation DIVISION OF RECREATION AND PARKS Mike Bullock Director and State Liaison Officer Florida Department of Environmental Protection Division of Recreation and Parks Marjory Stoneman Douglas Building 3900 Commonwealth Boulevard Tallahassee, Florida 32399-3000 The Florida Department of Environmental Protection is an equal opportunity agency, offering all persons the benefits of participating in each of its programs and competing in all areas of employment regardless of race, color, religion, sex, national origin, age, disability or other non-merit factors. OUTDOOR RECREATION IN FLORIDA — 2008 A Comprehensive Program For Meeting Florida’s Outdoor Recreation Needs State of Florida, Department of Environmental Protection Division of Recreation and Parks Tallahassee, Florida Outdoor Recreation in Florida, 2008 Table of Contents PAGE Chapter 1: Introduction and Background.............................................................................. 1-1 Purpose and Scope of the Plan ........................................................................................1-1 Outdoor Recreation - A Legitimate Role for Government................................................1-3 Outdoor Recreation Defined..............................................................................................1-3 Roles in Providing Outdoor Recreation ............................................................................1-4 Need