Orv Final Text 8/15

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Building 27, Suite 3 Fort Missoula Road Missoula, MT 59804

Photo by Louis Kamler. www.nationalforests.org Building 27, Suite 3 Fort Missoula Road Missoula, MT 59804 Printed on recycled paper 2013 ANNUAL REPORT Island Lake, Eldorado National Forest Desolation Wilderness. Photo by Adam Braziel. 1 We are pleased to present the National Forest Foundation’s (NFF) Annual Report for Fiscal Year 2013. During this fourth year of the Treasured Landscapes campaign, we have reached $86 million in both public and private support towards our $100 million campaign goal. In this year’s report, you can read about the National Forests comprising the centerpieces of our work. While these landscapes merit special attention, they are really emblematic of the entire National Forest System consisting of 155 National Forests and 20 National Grasslands. he historical context for these diverse and beautiful Working to protect all of these treasured landscapes, landscapes is truly inspirational. The century-old to ensure that they are maintained to provide renewable vision to put forests in a public trust to secure their resources and high quality recreation experiences, is National Forest Foundation 2013 Annual Report values for the future was an effort so bold in the late at the core of the NFF’s mission. Adding value to the 1800’s and early 1900’s that today it seems almost mission of our principal partner, the Forest Service, is impossible to imagine. While vestiges of past resistance what motivates and challenges the NFF Board and staff. to the public lands concept live on in the present, Connecting people and places reflects our organizational the American public today overwhelmingly supports values and gives us a sense of pride in telling the NFF maintaining these lands and waters in public ownership story of success to those who generously support for the benefit of all. -

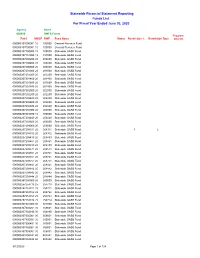

Funds List for Fiscal Year Ended June 30, 2020

Statewide Financial Statement Reporting Funds List For Fiscal Year Ended June 30, 2020 Agency Name 000000 SWFS Funds Program Fund SWGF SWF Fund Name Status Restriction % Restriction Type Interest 000000101000001 10 100000 General Revenue Fund 000000107000001 10 100000 General Revenue Fund 000000107100000 10 100000 Statewide GASB Fund 000000157151000 15 151000 Statewide GASB Fund 000000207200200 20 200200 Statewide GASB Fund 000000207200400 20 200400 Statewide GASB Fund 000000207200800 20 200800 Statewide GASB Fund 000000207201000 20 201000 Statewide GASB Fund 000000207201200 20 201200 Statewide GASB Fund 000000207201400 20 201400 Statewide GASB Fund 000000207201600 20 201600 Statewide GASB Fund 000000207201800 20 201800 Statewide GASB Fund 000000207202000 20 202000 Statewide GASB Fund 000000207202200 20 202200 Statewide GASB Fund 000000207202400 20 202400 Statewide GASB Fund 000000207202600 20 202600 Statewide GASB Fund 000000207202800 20 202800 Statewide GASB Fund 000000207203000 20 203000 Statewide GASB Fund 000000207203200 10 100000 Statewide GASB Fund 000000207203400 20 203400 Statewide GASB Fund 000000207203600 20 203600 Statewide GASB Fund 000000207208000 20 208000 Statewide GASB Fund 000000207208311 20 208311 Statewide GASB Fund 1 L 000000207208312 20 208312 Statewide GASB Fund 000000207208439 20 208439 Statewide GASB Fund 000000207208461 20 208461 Statewide GASB Fund 000000207208489 20 208489 Statewide GASB Fund 000000207208571 20 208571 Statewide GASB Fund 000000207208701 20 208701 Statewide GASB Fund 000000207208721 20 208721 -

2018 Annual Report

2018 ANNUAL REPORT Fish &Wildlife Foundation SECURING FLORIDA’S NATURAL FUTURE of FloridaT TM MESSAGE FROM THE CHAIRMAN Since our founding in 1994, the Fish & Wildlife and other gamefish populations are healthy. New we’re able to leverage your gifts many times Foundation of Florida has worked to ensure Florida wildlife preserves have been created statewide to over. From gopher tortoises and Osceola turkeys remains a place of unparalleled natural beauty, protect terns, plovers, egrets and other colonial to loggerhead turtles and snook, there are few iconic wildlife, world-famous ecosystems and nesting birds. Since 2010, more than 2.3 million native fish, land animals and habitats that aren’t unbounded outdoor recreational experiences. Florida children have participated in outdoor benefiting from your support. programs, thanks to the 350 private and public We’ve raised and given away more than $32 Please enjoy this annual report and visit our members of the Florida Youth Conservation million over that time, mostly to the Florida Fish website at www.wildlifeflorida.org. For 25 years, Centers Network, which includes FWC’s new and Wildlife Conservation Commission (FWC) for we’ve worked quietly behind the scenes to make Suncoast Youth Conservation Center in Apollo Table of Contents which we are a Citizens Support Organization. good things happen. With your continued help, Beach and the Everglades Youth Conservation But we are also Florida’s largest private funder of we’ll do so much more. WHO WE ARE 3 Camp in Palm Beach County. outdoor education and camps for youth, and we’re WHAT WE DO 9 one of the most important funders of freshwater Our Foundation supports all of this. -

Jim Stevenson Resource Manager of the Year” 2012 Awards Are Announced!

“Jim Stevenson Resource Manager of the Year” 2012 Awards are Announced! Author: Dana C. Bryan, Environmental Policy Coordinator, Florida Park Service Published in the CFEOR Updates Newsletter on May 10, 2013. The spectacular public conservation and recreation lands of Florida are managed by hundreds of skilled staff chiefly from three state agencies: the Florida Forest Service; the Florida Park Service; and the Florida Fish and Wildlife Conservation Commission. The Jim Stevenson Resource Manager of the Year Award is given annually by proclamation of the Governor and Cabinet to recognize a superior land manager from each of these agencies. The award is named for Jim A. Stevenson, who contributed tireless leadership in ecosystem management, prescribed burning, exotic plant control, and springs protection during his long career with DEP’s Florida Park Service and Division of State Lands. The 2012 winners are: Chris Colburn, Forestry Supervisor II, Tallahassee Forestry Center, Florida Forest Service, Department of Agriculture and Consumer Services Chris Colburn works on Lake Talquin State Forest (LTSF), which is comprised of fifteen tracts totaling 19,347 acres in Leon, Gadsden, Liberty, and Wakulla counties. Chris provides all of the resource management planning to meet annual and 10-year management objectives for the Forest, provides all of the resource management oversight, and performs most of the silviculture and restoration fieldwork. In addition, Chris has filled in as the State Lands Forester on Wakulla State Forest and has provided technical support to both Wakulla and Tate’s Hell state forests. These are examples of his desire to provide quality management on all public lands. -

MSRP Appendix A

APPENDIX A: RECOVERY TEAM MEMBERS Multi-Species Recovery Plan for South Florida Appendix A. Names appearing in bold print denote those who authored or prepared Appointed Recovery various components of the recovery plan. Team Members Ralph Adams Geoffrey Babb Florida Atlantic University The Nature Conservancy Biological Sciences 222 South Westmonte Drive, Suite 300 Boca Raton, Florida 33431 Altimonte Springs, Florida 32714-4236 Ross Alliston Alice Bard Monroe County, Environmental Florida Department of Environmental Resource Director Protection 2798 Overseas Hwy Florida Park Service, District 3 Marathon , Florida 33050 1549 State Park Drive Clermont, Florida 34711 Ken Alvarez Florida Department of Enviromental Bob Barron Protection U.S. Army Corps of Engineers Florida Park Service, 1843 South Trail Regulatory Division Osprey, Florida 34229 P.O. Box 4970 Jacksonville, Florida 32232-0019 Loran Anderson Florida State University Oron L. “Sonny” Bass Department of Biological Science National Park Service Tallahassee, Florida 32306-2043 Everglades National Park 40001 State Road 9336 Tom Armentano Homestead, Florida 33034-6733 National Park Service Everglades National Park Steven Beissinger 40001 State Road 9336 Yale University - School of Homestead, Florida 33034-6733 Forestry & Environmental Studies Sage Hall, 205 Prospect Street David Arnold New Haven, Connecticut 06511 Florida Department of Environmental Protection Rob Bennetts 3900 Commonwealth Boulevard P.O. Box 502 Tallahassee, Florida 32399-3000 West Glacier, Montana 59936 Daniel F. Austin Michael Bentzien Florida Atlantic University U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service Biological Sciences Jacksonville Field Office 777 Glades Road 6620 Southpoint Drive South, Suite 310 Boca Raton, Florida 33431 Jacksonville, Florida 32216-0912 David Auth Nancy Bissett University of Florida The Natives Florida Museum of Natural History 2929 J.B. -

Fight Speciesism 8

ISSUE 8 --- SPRING 2009 FREE / DONATION anti -speciesist, anti -capit alist, abolitionist direct action news NETHERLANDS SPAIN MEXICO CITY ITALY SHAC 7 SOLIDARITY / OPERATION SINKING SHIP HUNT SABBING / MINK RELEASED / INTERNATIONAL ACTIONS MAX MARA / MONKEYS FIGHT BACK / BULLRING RIOTS ALF NETHERLANDS / ELF MEXICO / PRISONER SUPPORT / + MORE RIOTING IN LONDON – BATTLE OF KENSINGTON TO THOSE WHO DREAM OF FREEDOM Two weeks into Israels latest war of aggression against the people of Palestine over 800 people are dead, over 257 of which are children. th Around the world there have been militant protests and on the 10 January saw the second UK national demonstration since the invasion took place in London. Between 50,000 and 100,000 people took part in the march, which went from London's Hyde Park to the Israeli embassy. Other demonstrations and actions took place across the country over the whole weekend. “Four shops in total had their windows put through, two starbucks, one very posh optitions and for good measure a very posh clothes shop called top gun (wall to wall fur coats) so was good day for everyone. The police where extremely violent and willingly pushed large crouds of protesters into and over rows of upturned barrier, this is when many injuries occurd. At least four police helmets, 3 riot shields and some other filth apparel was conviscated by the protesters who used it to defend themselves against the pressing riot cops. Fireworks where thrown at police and the bastards in uniform FIVE TRUCKS TORCHED AT CHICKEN SLAUGHTERHOUSE - NORWAY where made to dance as they went off.” - ARA EDO SMASHED – SOLIDARITY WITH THE PEOPLE OF GAZA 2. -

Ross Prairie State Forest Te Florida Scrub Jay Makes Ross Prairie State Forest Its Home

STATE FOREST SPOTLIGHT Tings to Know When Visiting Florida Forest Service Florida Scrub Jay Ross Prairie State Forest Te Florida Scrub Jay makes Ross Prairie State Forest its home. Tis bird was federally listed as a threatened species in 1987 primarily because of habitat loss, fragmentation and degradation. Florida Scrub Jays are picky about habitat, restricted to thickets of oak • Te Florida Park Service’s trailhead and Ross Prairie scrub 3 to 10 feet in height with areas of bare sand campground gates close at 7 P.M. during interspersed. Te habitat needs to be dry and well daylight savings time. State Forest drained. Unfortunately for the Scrub Jay, this same habitat is desirable for urban development because of the well-drained soils. • Pets are welcome but must remain on a leash. Florida Scrub Jays are ofen confused with the more common Blue Jay because they are similar in size. • Do not create new trails. However, Scrub Jays have no crest, are much duller in overall color, have no bold black markings, and lack white-tipped wings and tail feathers. Te most common • All horses must have proof of current negative Scrub Jay vocalization is a loud scratchy weep. Te Coggins test results when on state lands. principal plant food for the Scrub Jay is the acorn. Te majority of acorns gathered, up to 6,000 per year, are hidden in the sand for future meals. • Take all garbage with you when you leave the forest. Containers are not provided. Love the state forests? So do we! • For primitive camping information visit FloridaForestService.ReserveAmerica.com. -

Historic Distributions of Wet Savannas in Tates Hell State Forest

HISTORIC DISTRIBUTION OF WET SAVANNAS IN TATE'S HELL STATE FOREST FINAL REPORT DECEMBER 1997 CAROLYN KINDELL, PRO.JECT MANAGER/EcOLOGIST '. I Historic Distribution of I Wet Savannas in I Tate's Hell State Forest I Final Report • for the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service I (Agreement #1448-0004-96-9102) and Northwest Florida Water Management District • • December 1997 • Carolyn Kindell, M Project Manager/Ecologist - � - Florida Natural Areas Inventory 1018 Thomasville Road, Suite #200c • Tallahassee, Florida 32303 (850) 224-8207 , http://www . fnai. org • Gary R. Knight, Program Director • • Cover Photographs: top: Wet prairie in Apalachicola National Forest, Ann Johnson, FNAI middle: 1942 BW aerial of a selected portion of Tate's Hell State Forest, National Archives, Washington, D.C. bottom: 1994 infrared aerial of a selected portion of Tate's Hell State Forest, National Aerial Photography Program, Photo Science, Inc., Gaithersburg, MD. Recommended Citation: Kindell, Carolyn. 1997. Historic Distribution of Wet Savannas in Tate's Hell State Forest. Final Report for the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service (Agreement #1448,0004,96,9102) and Northwest Florida Water Management District. Florida Natural Areas Inventory, Tallahassee, Florida. ABSTRACT Tate's Hell State Forest is currently 131,000 acres or low pine tJatwoods, pine plantation, swamps, and coastal scmh in Franklin and Liberty Counties, Plorida and is managed by the Florida Department of Agriculture's Division of Forestry (FDOF). The original 214,000 acre tract was proposed for purchase under the Florida Conservation and Recreation Lands (CARL) program in 1992, and acquisition is still underway. The Tate's Hell tract is vital to the maintenance of water quality in Apalachicola Bay and provides critical habitat for rare plants, animals, and natural communities. -

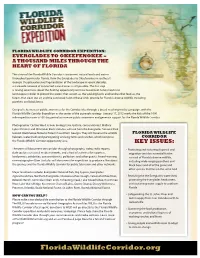

Everglades to Okeefenokee – a Thousand Miles Through the Heart of Florida

FLORIDA WILDLIFE CORRIDOR EXPEDITION: EVERGLADES TO OKEEFENOKEE – A THOUSAND MILES THROUGH THE HEART OF FLORIDA The vision of the Florida Wildlife Corridor is to connect natural lands and waters throughout peninsular Florida, from the Everglades to Okeefenokee in southeast Georgia. Despite extensive fragmentation of the landscape in recent decades, a statewide network of connected natural areas is still possible. The first step is raising awareness about the fleeting opportunity we have to connect natural and rural landscapes in order to protect the waters that sustain us, the working farms and ranches that feed us, the forests that clean our air, and the combined habitat these lands provide for Florida’s diverse wildlife, including panthers and black bears. Our goal is to increase public awareness for the Corridor idea through a broad-reaching media campaign, with the Florida Wildlife Corridor Expedition as the center of the outreach strategy. January 17, 2012 marks the kick off the 1000 mile expedition over a 100 day period to increase public awareness and generate support for the Florida Wildlife Corridor. Photographer Carlton Ward Jr, bear biologist Joe Guthrie, conservationist Mallory Lykes Dimmitt and filmmaker Elam Stoltzfus will trek from the Everglades National Park toward Okefenokee National Forest in southern Georgia. They will traverse the wildlife FLORIDA WILDLIFE habitats, watersheds and participating working farms and ranches, which comprise CORRIDOR the Florida Wildlife Corridor opportunity area. KEY ISSUES: The team will document the corridor through photography, video, radio reports, • Protecting and restoring dispersal and daily updates on social media networks, and a host of activities for reporters, migration corridors essential for the landowners, celebrities, conservationists, politicians and other guests. -

Il Modello Shac the Militant Forces Against

Il “modello SHAC” è applicabile anche ad altre lotte e a contesti diversi da quello della liberazione animale? In quali condizioni? Quali sono i suoi THE MILITANT FORCES vantaggi e difetti? Oggi che una delle campagne di pressione più importanti, a livello glo- AGAINST HLS (MFAH) bale, del movimento di liberazione animale si è conclusa (è dell’estate 2014 il comunicato uffi ciale che pone fi ne alla campagna), è tempo di rifl ettere sugli aspetti negativi e positivi di questo modello di attivismo e militanza, che è quasi riuscito a mettere in ginocchio una multinazionale della vivisezione, ma infi ne ha subìto i colpi di una durissima repressione, che lo stesso movimento non era preparato per aff rontare. Un modello ba- sato sulla diversità di tattiche mirate a uno stesso obiettivo, la chiusura di una multinazionale o di un luogo di tortura, attraverso l’attacco ai suoi clienti, fornitori, azionisti e a tutte le altre aziende che ne rendono pos- sibile il business. Quel che è fuori da ogni dubbio è che questa campagna non avrebbe potuto ottenere le vittorie che ha ottenuto se non fosse stata supportata dalle centinaia di azioni dirette (sabotaggi, liberazioni, in- cendi, minacce e imbrattamenti) realizzate nel corso degli ultimi 10 anni dall’ALF, dalle Militant Forces Against HLS e da altri gruppi o individui determinati a passare all’azione. IL MODELLO SHAC UNA RACCOLTA DI COMUNICATI DELLE AZIONI FIRMATE ‘MILITANT FORCES AGAINST HLS’ TRA IL 2009 E IL 2012 A SEGUIRE UN’ANALISI DELLA STRATEGIA DI SHAC E LA SUA POSSIBILE 56 1 APPLICABILITÀ AD ALTRE LOTTE. -

Creating a Greenway in Northern Florida

Creating a Greenway in Northern Florida Congressional District: 4 Florida Baker and Columbia Counties Member: Ander Crenshaw Location On the Osceola National Forest in northeastern Florida. Acquired to Date Method Acres Cost ($) Purchase 45,370 $16,799,000 Purpose Conserve and enhance critical scenic, recreational, and wildlife Exchange 18,528 n/a resources; achieve landscape scale conservation with an Donation 7,000 n/a emphasis on restoration, watersheds, natural treasures, climate Partners 40,765 $31,500,000+ change, sustainable bioenergy, and recreation. President’s Buget FY2012 Purchase Acres Cost ($) SWC 435 $1,000,000 Pending Future Action Method Acres* Cost ($) SMR 1,060 $3,500,000 Pending 3,500 $9,000,000 Partners The Suwannee River Water Management District will contribute up to $600,000 towards the purchase of the Suwannee tract. The Trust for Public Land has contributed to pre-acquisition work and is holding the St. Mary’s tract pending Federal purchase. Cooperators State of Florida, Columbia County, Baker County, Florida Sierra Club, The Nature Conservancy, National and Supporters Florida Wildlife Federations, Defenders of Wildlife, Florida and National Audubon Societies, Save the Panther, Habitat for Bears, Florida Defenders of the Environment, Ducks Unlimited. Project These acquisitions are located near the Interstate-10 corridor west of Jacksonville and adjacent to the Osceola Description National Forest. As one of the major export/import locations in the South, the Interstate 10 corridor is under constant pressure as industrial and residential developments expand from suburban Jacksonville, with major industrial growth expected over the next 12 to 36 months. Acquiring these tracts in advance of new development will prevent conversion to other uses. -

Schedule of Proposed Action (SOPA) 10/01/2018 to 12/31/2018 National Forests in Florida This Report Contains the Best Available Information at the Time of Publication

Schedule of Proposed Action (SOPA) 10/01/2018 to 12/31/2018 National Forests In Florida This report contains the best available information at the time of publication. Questions may be directed to the Project Contact. Expected Project Name Project Purpose Planning Status Decision Implementation Project Contact National Forests In Florida, Occurring in more than one District (excluding Forestwide) R8 - Southern Region Apalachicola Route - Recreation management On Hold N/A N/A Harold Shenk Designation Revision - Road management 850-926-3561 x 6502 EA [email protected] Description: The Apalachicola National Forest is evaluating monitoring information and public comments received during the first year of implementation of the 2007 Apalachicola National Forest Motorized Route Designation for a possible revision. Location: UNIT - Apalachicola Ranger District, Wakulla Ranger District. STATE - Florida. COUNTY - Calhoun, Leon, Liberty. LEGAL - Not Applicable. Aplachicola National Forest. National Forests In Florida Apalachicola Ranger District (excluding Projects occurring in more than one District) R8 - Southern Region Big Gully Analysis Area - Recreation management In Progress: Expected:09/2018 10/2018 Branden Tolver EA - Wildlife, Fish, Rare plants Scoping Start 03/17/2017 936-344-6205 - Forest products Est. Comment Period Public [email protected] - Vegetation management Notice 07/2018 (other than forest products) - Fuels management Description: The proposed action would include treatments such as first thinning of young pine plantations, intermediate thinning of mature slash and longleaf stands, and herbicide application for timber stand improvement. Web Link: http://www.fs.usda.gov/project/?project=50776 Location: UNIT - Apalachicola Ranger District. STATE - Florida. COUNTY - Liberty. LEGAL - Not Applicable. The project area is located in compartments 15, 16, and 23 and is within the Apalachicola Ranger District, Apalachicola National Forest, Liberty County, FL.