State-Owned Lands in the Eastern United States: Lessons from State Land Management in Practice

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

National Forests in Michigan

OriqiMI from Digitized by Go gle UNIVERSITY OF MICHIGAN NATIONAL FORESTS IN MICHIGAN UNITED STATES DEPARTMENT OF AGRICULTURE FOREST SERVICE NORTH CENTRAL REGION • MILWAUKEE, WIS. ON THE COVER. —Great Conglomerate Falls on the Black River. p-3e«M ERRATA Page Line 5 3 97,000,000 should be 45,000,000. 7 4 Porcupine should not be listed vvilh fur bearers. 17 7 Si.o'jld read "the red pine by its ClUoLC"G Cf t»Vj". 44 2-3 Should read "4 rniies east of Munising". UNITED STATES GOVERNMENT PRINTING OFFICE WASHINGTON : 1941 sEr^ •*«$• . AU TRAIN FALLS ON THE HIAWATHA NATIONAL FOREST. Drama of Michigan Forests DRAMA of the forests of Michigan has been written in several acts THEeach with its colorful pageantry. The action has concerned the magni ficent woodlands of the redman, the rapid depletion of those forests in the last century, and their slow but sure rebuilding in the present. The elusive "northwest passage" to China, Indian furs and Indian souls, iron and land and copper brought the white men to Michigan. In 1621, only 1 year after the Pilgrims landed at Plymouth Rock, young Etienne Brule, protege of Champlain, reached Lake Superior and was disappointed to find its waters fresh. Thirteen years later, Jean Nicolet, another protege of the French governor of Canada, entered the unknown Lake Michigan through the Straits of Mackinac. Though he never found the longed-for route to the Orient, Nicolet did initiate the French fur trade with the Indians in this territory. Heroic followers of Brule and Nicolet were the Jesuit fathers Jogues and Raymbault, who preached to the Ojibwas in 1641 at Sault Ste. -

Six Nations Unit Management Plan Final

New York State Department of Environmental Conservation Division of Lands & Forests SIX NATIONS UNIT MANAGEMENT PLAN FINAL Schuyler County towns of Orange, Dix, Tyrone and Reading Steuben County towns of Bradford, Hornby, Campbell and Erwin November, 2013 Lead Agency: NYS Department of Environmental Conservation Region 8 Sub-Office 7291 Coon Rd. Bath, New York 14810 ANDREW CUOMO, Governor JOE MARTENS, Commissioner ROB DAVIES, State Forester ANDREW M. CUOMO JOE MARTENS GOVERNOR COMMISSIONER STATE OF NEW YORK DEPARTMENT OF ENVIRONMENTAL CONSERVATION ALBANY, NEW YORK 12233-1010 MEMORANDUM TO: The Record FROM: Joseph J. Marte~l DATE: ()c.!- '30, ;!-013 SUBJECT: Final Six Nations UMP The Unit Management Plan for the Six Nations unit has been completed. The Plan is consistent with Department policy and procedure, involved public participation and is consistent with the Environmental Conservation Law, Rules and Regulations. The plan includes management objectives for a ten year period and is hereby approved and adopted. NYS Department of Environmental Conservation’s Mission “The quality of our environment is fundamental to our concern for the quality of life. It is hereby declared to be the policy of the State of New York to conserve, improve and protect its natural resources and environment and to prevent, abate and control water, land and air pollution, in order to enhance the health, safety and welfare of the people of the state and their overall economic and social well-being.” - Environmental Conservation Law 1-0101(1) PREFACE It is the policy of the New York State Department of Environmental Conservation (NYS DEC) to manage state lands for multiple benefits to serve the people of New York State. -

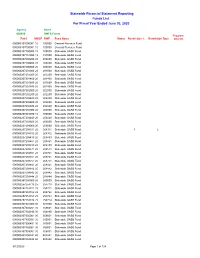

Funds List for Fiscal Year Ended June 30, 2020

Statewide Financial Statement Reporting Funds List For Fiscal Year Ended June 30, 2020 Agency Name 000000 SWFS Funds Program Fund SWGF SWF Fund Name Status Restriction % Restriction Type Interest 000000101000001 10 100000 General Revenue Fund 000000107000001 10 100000 General Revenue Fund 000000107100000 10 100000 Statewide GASB Fund 000000157151000 15 151000 Statewide GASB Fund 000000207200200 20 200200 Statewide GASB Fund 000000207200400 20 200400 Statewide GASB Fund 000000207200800 20 200800 Statewide GASB Fund 000000207201000 20 201000 Statewide GASB Fund 000000207201200 20 201200 Statewide GASB Fund 000000207201400 20 201400 Statewide GASB Fund 000000207201600 20 201600 Statewide GASB Fund 000000207201800 20 201800 Statewide GASB Fund 000000207202000 20 202000 Statewide GASB Fund 000000207202200 20 202200 Statewide GASB Fund 000000207202400 20 202400 Statewide GASB Fund 000000207202600 20 202600 Statewide GASB Fund 000000207202800 20 202800 Statewide GASB Fund 000000207203000 20 203000 Statewide GASB Fund 000000207203200 10 100000 Statewide GASB Fund 000000207203400 20 203400 Statewide GASB Fund 000000207203600 20 203600 Statewide GASB Fund 000000207208000 20 208000 Statewide GASB Fund 000000207208311 20 208311 Statewide GASB Fund 1 L 000000207208312 20 208312 Statewide GASB Fund 000000207208439 20 208439 Statewide GASB Fund 000000207208461 20 208461 Statewide GASB Fund 000000207208489 20 208489 Statewide GASB Fund 000000207208571 20 208571 Statewide GASB Fund 000000207208701 20 208701 Statewide GASB Fund 000000207208721 20 208721 -

2018 Annual Report

2018 ANNUAL REPORT Fish &Wildlife Foundation SECURING FLORIDA’S NATURAL FUTURE of FloridaT TM MESSAGE FROM THE CHAIRMAN Since our founding in 1994, the Fish & Wildlife and other gamefish populations are healthy. New we’re able to leverage your gifts many times Foundation of Florida has worked to ensure Florida wildlife preserves have been created statewide to over. From gopher tortoises and Osceola turkeys remains a place of unparalleled natural beauty, protect terns, plovers, egrets and other colonial to loggerhead turtles and snook, there are few iconic wildlife, world-famous ecosystems and nesting birds. Since 2010, more than 2.3 million native fish, land animals and habitats that aren’t unbounded outdoor recreational experiences. Florida children have participated in outdoor benefiting from your support. programs, thanks to the 350 private and public We’ve raised and given away more than $32 Please enjoy this annual report and visit our members of the Florida Youth Conservation million over that time, mostly to the Florida Fish website at www.wildlifeflorida.org. For 25 years, Centers Network, which includes FWC’s new and Wildlife Conservation Commission (FWC) for we’ve worked quietly behind the scenes to make Suncoast Youth Conservation Center in Apollo Table of Contents which we are a Citizens Support Organization. good things happen. With your continued help, Beach and the Everglades Youth Conservation But we are also Florida’s largest private funder of we’ll do so much more. WHO WE ARE 3 Camp in Palm Beach County. outdoor education and camps for youth, and we’re WHAT WE DO 9 one of the most important funders of freshwater Our Foundation supports all of this. -

Jim Stevenson Resource Manager of the Year” 2012 Awards Are Announced!

“Jim Stevenson Resource Manager of the Year” 2012 Awards are Announced! Author: Dana C. Bryan, Environmental Policy Coordinator, Florida Park Service Published in the CFEOR Updates Newsletter on May 10, 2013. The spectacular public conservation and recreation lands of Florida are managed by hundreds of skilled staff chiefly from three state agencies: the Florida Forest Service; the Florida Park Service; and the Florida Fish and Wildlife Conservation Commission. The Jim Stevenson Resource Manager of the Year Award is given annually by proclamation of the Governor and Cabinet to recognize a superior land manager from each of these agencies. The award is named for Jim A. Stevenson, who contributed tireless leadership in ecosystem management, prescribed burning, exotic plant control, and springs protection during his long career with DEP’s Florida Park Service and Division of State Lands. The 2012 winners are: Chris Colburn, Forestry Supervisor II, Tallahassee Forestry Center, Florida Forest Service, Department of Agriculture and Consumer Services Chris Colburn works on Lake Talquin State Forest (LTSF), which is comprised of fifteen tracts totaling 19,347 acres in Leon, Gadsden, Liberty, and Wakulla counties. Chris provides all of the resource management planning to meet annual and 10-year management objectives for the Forest, provides all of the resource management oversight, and performs most of the silviculture and restoration fieldwork. In addition, Chris has filled in as the State Lands Forester on Wakulla State Forest and has provided technical support to both Wakulla and Tate’s Hell state forests. These are examples of his desire to provide quality management on all public lands. -

Draft Mcdonough Unit Management Plan

McDonough UNIT MANAGEMENT PLAN DRAFT Towns of McDonough, Preston & Smithville County of Chenango June 2019 DIVISION OF LANDS AND FORESTS Bureau of State Land Management, Region 7 2715 State Highway 80 Sherburne, NY 13460 www.dec.ny.gov McDonough UNIT MANAGEMENT PLAN COVERING FOUR STATE FORESTS IN CHENANGO COUNTY, NY: McDONOUGH - CHENANGO R.A. # 1 & 11 LUDLOW CREEK - CHENANGO R.A.# 6 GENEGANTSLET-CHENANGO R.A. # 26 March 2019 Prepared By: Gregory Owens, Senior Forester Andrew Blum, Senior Forester Christopher Sprague, Senior Forester New York State Department of Environmental Conservation Lands & Forests Office 2715 State Highway 80 Sherburne, New York 13460 607-674-4036 Contributing Staff: Scott Prindle, Aquatic Biologist Linda Collart, Mineral Resources Supervisor Glenn Wolford, Regional Supervisor, Real Property Richard Chapin, Operations Supervisor 1 DEC’s Mission "The quality of our environment is fundamental to our concern for the quality of life. It is hereby declared to be the policy of the State of New York to conserve, improve and protect its natural resources and environment and to prevent, abate and control water, land and air pollution, in order to enhance the health, safety and welfare of the people of the state and their overall economic and social well-being." - Environmental Conservation Law 1-0101(1) * Highlighted (bold) terms are defined in the Glossary. Vision Statement State Forests on the McDonough Unit will be managed in a sustainable manner by promoting ecosystem health, enhancing landscape biodiversity, protecting soil productivity and water quality. In addition, the State Forests on this unit will continue to provide the many recreational, social and economic benefits valued so highly by the people of New York State. -

Ross Prairie State Forest Te Florida Scrub Jay Makes Ross Prairie State Forest Its Home

STATE FOREST SPOTLIGHT Tings to Know When Visiting Florida Forest Service Florida Scrub Jay Ross Prairie State Forest Te Florida Scrub Jay makes Ross Prairie State Forest its home. Tis bird was federally listed as a threatened species in 1987 primarily because of habitat loss, fragmentation and degradation. Florida Scrub Jays are picky about habitat, restricted to thickets of oak • Te Florida Park Service’s trailhead and Ross Prairie scrub 3 to 10 feet in height with areas of bare sand campground gates close at 7 P.M. during interspersed. Te habitat needs to be dry and well daylight savings time. State Forest drained. Unfortunately for the Scrub Jay, this same habitat is desirable for urban development because of the well-drained soils. • Pets are welcome but must remain on a leash. Florida Scrub Jays are ofen confused with the more common Blue Jay because they are similar in size. • Do not create new trails. However, Scrub Jays have no crest, are much duller in overall color, have no bold black markings, and lack white-tipped wings and tail feathers. Te most common • All horses must have proof of current negative Scrub Jay vocalization is a loud scratchy weep. Te Coggins test results when on state lands. principal plant food for the Scrub Jay is the acorn. Te majority of acorns gathered, up to 6,000 per year, are hidden in the sand for future meals. • Take all garbage with you when you leave the forest. Containers are not provided. Love the state forests? So do we! • For primitive camping information visit FloridaForestService.ReserveAmerica.com. -

United States Department of the Interior

United States Department of the Interior FISH AND WILDLIFE SERVICE East Lansing Field Office (ES) 2651 Coolidge Road, Suite 101 IN REPLY REFER TO: East Lansing, Michigan 48823-6316 May 1, 2015 Leslie Auriermno, Forest Supervisor Huron-Manistee National Forests 1755 South Mitchell St. Cadillac, MI 49601-8533 Re: Fonnal Section 7 Consultation on the Huron-Manistee National Forests' Ongoing and Planned Actions- Log# 1O-R3-ELF0-03 Dear Ms. Amiemmo: This letter transmits the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service's Biological Opinion for the Huron Manistee National Forests' (HMNF) ongoing and planned actions in accordance with Section 7 of the Endangered Species Act (Act) of 1973, as amended (16 U.S .C. 1531 et seq.). The HMNF detennined that the proposed actions were "Likely to Adversely Affect" the norihern long-eared bat (Myotis septentrionalis). We base the enclosed Opinion on information provided in several documents, including your northern long-eared project matrix and Biological Assessment, the Programmatic Biological Assessment and Opinion for the HMNF's Land and Resource Management Plan, and our April 1, 2015, Conference Opinion. Other sources ofinfonnation include previous telephone conversations, e-mails and meetings. A complete administrative record of this consultation is on file at our East Lansing Field Office. After reviewing the current status of northern long-eared bat, the environmental baseline for the action area, the effects of the proposed action, and the cumulative effects, it is our biological opinion that the action, as proposed, is not likely to jeopardize the continued existence of northern long-eared bat With respect to ESA compliance, all aspects of the project description are binding. -

November/December 2010

90 Years of Trail Magic More Trail Magic Ahead What we’ve accomplished: Our trails, volunteers, partners, a timeline in pictures. and trail users will all be more SEE PAGES 6 & 7 numerous and more diverse. READ MORE ON PAGE 3 O UR 90TH YEAR November/December 2010 New York-New Jersey Trail Conference — Connecting People with Nature since 1920 www.nynjtc.org Trail Conference Aids Efforts New Teatown- The Trail Route TKT, which is blazed in distinctive pUrple, Kitchawan Trail begins at the North CoUnty Trailway near to Revitalize Lenape Trail and RoUte 134, and makes its way west across Links Multiple the Kitchawan Reserve near RoUte 134 in Liberty Water Gap Trail in NJ the soUtheast corner of Yorktown. When it By Steve Marano Parks and Trails reaches Arcady Road, it crosses onto DEP land and continUes throUgh the woods and he 34-mile Lenape Trail in Essex in Westchester meadows of Stayback Hill. CoUnty, NJ, is enjoying a bUrst of The trail then follows Croton Lake TvolUnteer energy and sUpport from On October 6, Westchester CoUnty’s trails Road, a lightly traveled and largely dirt-sUr - the Trail Conference, which is providing got a big boost in connectivity with the face road, in order to pass Under the north expertise in trail work and volUnteer train - opening of the Teatown-Kitchawan Trail and soUth lanes of the Taconic State Park - ing and sUpport to area residents who seek (TKT). The new east-west trail links the way. Once Under the parkway, the trail to revitalize the trail. -

Summer 2016 New York–North Jersey Chapter

& Trails Waves News from the Appalachian Mountain Club Volume 38, Issue 2 • Summer 2016 New York–North Jersey Chapter OPEN FOR BUSINESS: the new Harriman Outdoor AMC TRAILS & WAVES SUMMER 2016 NEW YORK - NORTH JERSEY CHAPTER 1 Center IN THIS ISSUE Chapter Picnic 3 The Woods Around Us 4 Our Public Lands 7 Leadership Workshop 13 Membership Chair 14 Thanks! 16 Letter to the Editor 18 Harriman FAQs 19 Fuel it Up 21 Book Review 24 Photo Contest 29 An Easy Access Wilderness? 30 Harriman Activities 34 Dunderberg Mountain 37 Message from the Chair ummer started early and outdoor This year we have also been working on a activities are going strong. We are solid Path to Leadership Program and S very excited about the opening of the Leadership Workshop. Excellence in Harriman Outdoor Center. For those of you outdoor leadership is part of the AMC who have not seen, we encourage you to join Vision 2020 and we are working with a work crew or take a tour. The camp opening Boston staff for the Workshop to be held is scheduled for July 2nd. Cabins are available September 23rd through September 25th. Our for rent, so get a group together and go! leaders are what set us apart from the many Contact [email protected] for more other groups in the area. Leaders have been information. The chapter has planned 19 polled and an agenda pulled together to offer weekend activities with programs for both advanced training and training for paddlers, hikers, cycling, trail maintainers, potential leaders. We hope many of you will leader training and much more. -

5 April 2019 Forester Seth Thomas, NYSDEC, P.O. Box 1316 Northville, NY 12134 Email: [email protected]

5 April 2019 Forester Seth Thomas, NYSDEC, P.O. Box 1316 Northville, NY 12134 Email: [email protected] RE: Draft Fulton County State Forests Unit Management Plan (UMP) Dear Seth, Thank you for the opportunity to comment on the Fulton County State Forests Unit Management Plan (UMP), including Lassellsville State Forest in the towns of Ephratah and Oppenheim; Peck Hill State Forest in the town of Johnstown; and Rockwood State Forest in the towns of Ephratah and Johnstown. Adirondack Mountain Club ADK is dedicated to protecting and advocating for New York State’s wild lands and waters while also teaching people how to enjoy natural places responsibly. Since 1922, the organization has offered people opportunities to stay and play in as well as protect, discover, and explore the outdoors. Today, ADK has 30,000 members in 27 chapters statewide and is served by a professional, year-round staff. The organization is recognized as a vital voice in the commitment to environmental stewardship and ethical outdoor recreation in New York State. ADK members hike, camp, snowshoe, cross-country ski, paddle, and cycle the lands and waters of the Adirondack Park and other state lands. Our members are also monitors and maintainers of trails and recreation infrastructure as well as watchdogs of public lands and watersheds to monitor for invasive species or irresponsible and destructive motorized trespass. We respectfully request that you consider the following concerns and comments outlined below. ADK Supports DEC in Banning ATVs on Fulton County State Forests and on All State Forest Lands ADK does not support the use of ATVs on New York State Land. -

Lake Huron, Off the Northeast Coast of Location

www.thunderbay.noaa.gov (989) 356-8805 Alpena, MI 49707 500 West Fletcher Street Heritage Center Great Lakes Maritime Contact Information N T ATIONAL ATIONAL HUNDER 83°30'W 83°15'W 83°00'W New Presque Isle Lighthouse Park 120 120 30 50 80 M 5 60 120 20 120 ARINE North Bay 90 10 70 82°45'W Wreck 50 110 130 5 100 Old Presque Isle Lighthouse Park 120 B 110 130 Presque Isle 40 140 Harbor S 120 ANCTUARY AY North Albany Point Cornelia B. 120 140 Windiate 140 130 Albany 110 • Types of Vessels Lost at Thunder Bay 110 130 South Albany Point Sail Powered • • • Scows Ships, Brigs, Schooners Barks 130 Lake Esau Grand Norman Island Wreck Point 130 140 Presque Isle 120 140 Lotus Lake 160 Typo Lake of the Florida • 140 Woods Steam Powered Brown • • 150 Island Sidewheelers Propellers John J. 110 170 Grand Audubon LAKE Lake 110 iver 110 R ll e 140 B 110 HURON 120 Whiskey False Presque Isle 150 Point Knight Bay • 110 Other 60 • • Unpowered Combustion Motor Powered 45°15'N 45°15'N Bell Czar 120 Bolton Point 140 Besser State Besser Bell Natural Area Wreck 120 Defiance (by quantity of loss for all wrecks) Cargoes Lost at Thunder Bay 130 • • • • 20 Iron ore Grain Coal Lumber products Ferron Point 120 Mackinaw 20 State Forest 30 Dump Scow 10 100 Rockport 130 70 80 • • • • 60 90 100 23 Middle Island Sinkhole Fish Salt Package freight Stone Long Portsmouth 50 Lake 40 100 120 Middle Island Middle Island Lighthouse 120 5 5 5 110 5 120 110 Middle 20 Lake • • • Copper ore Passengers Steel Monaghan Point New Orleans 100 120 90 220 Long Lake Creek 20 Morris D.M.