ACE Inhibitors and Arbs: Managing Potassium and Renal Function

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A Comparison of the Tolerability of the Direct Renin Inhibitor Aliskiren and Lisinopril in Patients with Severe Hypertension

Journal of Human Hypertension (2007) 21, 780–787 & 2007 Nature Publishing Group All rights reserved 0950-9240/07 $30.00 www.nature.com/jhh ORIGINAL ARTICLE A comparison of the tolerability of the direct renin inhibitor aliskiren and lisinopril in patients with severe hypertension RH Strasser1, JG Puig2, C Farsang3, M Croket4,JLi5 and H van Ingen4 1Technical University Dresden, Heart Center, University Hospital, Dresden, Germany; 2Department of Internal Medicine, La Paz Hospital, Madrid, Spain; 31st Department of Internal Medicine, Semmelweis University, Budapest, Hungary; 4Novartis Pharma AG, Basel, Switzerland and 5Novartis Institutes for Biomedical Research, Cambridge, MA, USA Patients with severe hypertension (4180/110 mm Hg) LIS 3.4%). The most frequently reported AEs in both require large blood pressure (BP) reductions to reach groups were headache, nasopharyngitis and dizziness. recommended treatment goals (o140/90 mm Hg) and At end point, ALI showed similar mean reductions from usually require combination therapy to do so. This baseline to LIS in msDBP (ALI À18.5 mm Hg vs LIS 8-week, multicenter, randomized, double-blind, parallel- À20.1 mm Hg; mean treatment difference 1.7 mm Hg group study compared the tolerability and antihyperten- (95% confidence interval (CI) À1.0, 4.4)) and mean sitting sive efficacy of the novel direct renin inhibitor aliskiren systolic blood pressure (ALI À20.0 mm Hg vs LIS with the angiotensin converting enzyme inhibitor À22.3 mm Hg; mean treatment difference 2.8 mm Hg lisinopril in patients with severe hypertension (mean (95% CI À1.7, 7.4)). Responder rates (msDBPo90 mm Hg sitting diastolic blood pressure (msDBP)X105 mm Hg and/or reduction from baselineX10 mm Hg) were 81.5% and o120 mm Hg). -

Ace Inhibitors (Angiotensin-Converting Enzyme)

Medication Instructions Ace Inhibitors (Angiotensin-Converting Enzyme) Generic Brand Benazepril Lotensin Captopril Capoten Enalapril Vasotec Fosinopril Monopril Lisinopril Prinivil, Zestril Do not Moexipril Univasc Quinapril Accupril stop taking Ramipril Altace this medicine Trandolapril Mavik About this Medicine unless told ACE inhibitors are used to treat both high blood pressure (hypertension) and heart failure (HF). They block an enzyme that causes blood vessels to constrict. This to do so allows the blood vessels to relax and dilate. Untreated, high blood pressure can damage to your heart, kidneys and may lead to stroke or heart failure. In HF, using by your an ACE inhibitor can: • Protect your heart from further injury doctor. • Improve your health • Reduce your symptoms • Can prevent heart failure. Generic forms of ACE Inhibitors (benazepril, captopril, enalapril, fosinopril, and lisinopril) may be purchased at a lower price. There are no “generics” for Accupril, Altace Mavik, and of Univasc. Thus their prices are higher. Ask your doctor if one of the generic ACE Inhibitors would work for you. How to Take Use this drug as directed by your doctor. It is best to take these drugs, especially captopril, on an empty stomach one hour before or two hours after meals (unless otherwise instructed by your doctor). Side Effects Along with needed effects, a drug may cause some unwanted effects. Many people will not have any side effects. Most of these side effects are mild and short-lived. Check with your doctor if any of the following side effects occur: • Fever and chills • Hoarseness • Swelling of face, mouth, hands or feet or any trouble in swallowing or breathing • Dizziness or lightheadedness (often a problem with the first dose) Report these side effects if they persist: • Cough – dry or continuing • Loss of taste, diarrhea, nausea, headache or unusual fatigue • Fast or irregular heartbeat, dizziness, lightheadedness • Skin rash Special Guidelines • Sodium in the diet may cause you to retain fluid and increase your blood pressure. -

Angioedema After Long-Term Use of an Angiotensin-Converting Enzyme Inhibitor

J Am Board Fam Pract: first published as 10.3122/jabfm.10.5.370 on 1 September 1997. Downloaded from BRIEF REPORTS Angioedema After Long-Term Use of an Angiotensin-Converting Enzyme Inhibitor Adriana]. Pavietic, MD Angioedema is an uncommon adverse effect of cyclobenzaprine, her angioedema was initially be angiotensin-converting enzyme (ACE) inhib lieved to be an allergic reaction to this drug, and itors. Its frequency ranges from 0.1 percent in pa it was discontinued. She was also given 125 mg of tients on captopril, lisinopril, and quinapril to 0.5 methylprednisolone intramuscularly. Her an percent in patients on benazepril. l Most cases are gioedema did not improve, and she returned to mild and occur within the first week of treat the clinic the following day. She was seen by an ment. 2-4 Recent reports indicate that late-onset other physician, who discontinued lisinopril, and angioedema might be more prevalent than ini her symptoms resolved within 24 hours. Mter her tially thought, and fatal cases have been de ACE inhibitor was discontinued, she experienced scribed.5-11 Many physicians are not familiar with more symptoms and an increased frequency of late-onset angioedema associated with ACE in palpitations, but she had no change in exercise hibitors, and a delayed diagnosis can have poten tolerance. A cardiologist was consulted, who pre tially serious consequences.5,8-II scribed the angiotensin II receptor antagonist losartan (initially at dosages of 25 mg/d and then Case Report 50 mg/d). The patient was advised to report any A 57-year-old African-American woman with symptoms or signs of angioedema immediately copyright. -

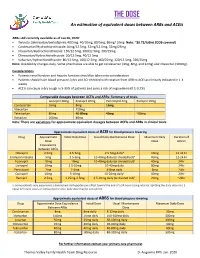

THE DOSE an Estimation of Equivalent Doses Between Arbs and Aceis

THE DOSE An estimation of equivalent doses between ARBs and ACEIs ARBs still currently available as of Jan 26, 2020: Twynsta (telmisartan/amlodipine): 40/5mg. 40/10mg, 80/5mg, 80mg/ 10mg Note: ~$0.73/tablet (ODB covered) Candesartan/Hydrochlorothiazide:16mg/12.5mg, 32mg/12.5mg, 32mg/25mg Irbesartan/Hydrochlorothiazide: 150/12.5mg, 300/12.5mg, 300/25mg Olmesartan/Hydrochlorothiaizde: 20/12.5mg, 40/12.5mg Valsartan/Hydrochlorothiazide: 80/12.5mg, 160/12.5mg, 160/25mg, 320/12.5mg, 320/25mg Note: Availability changes daily. Some pharmacies are able to get candesartan (4mg, 8mg, and 32mg) and irbesartan (300mg). Considerations Patients renal function and hepatic function should be taken into consideration Patients should have blood pressure, lytes and SCr checked with rotation from ARB to ACEI as clinically indicated in 1-4 weeks ACEIs can cause a dry cough in 5-35% of patients and carry a risk of angioedema (0.1-0.2%) Comparable dosages between ACEIs and ARBs- Summary of trials Lisinopril 20mg Enalapril 20mg Perindopril 4mg Ramipril 10mg Candesartan 16mg 8mg 16mg Irbesartan 150mg Telmisartan 80mg 40-80mg 40mg ~80mg Valsartan 160mg 80mg Note: There are variations for approximate equivalent dosages between ACEIs and ARBs in clinical trials. Approximate equivalent doses of ACEI for blood pressure lowering Drug Approximate Initial Daily Dose Usual Daily Maintenance Dose Maximum Daily Duration of Dose Dose Action Equivalence Between ACEIs Cilazapril 2.5mg 2.5-5mg 2.5-5mg dailya 10mg 12-24 hr Enalapril maleate 5mg 2.5-5mg 10-40mg daily (or divided bid)a 40mg 12-24 hr Fosinopril 10mg 10mg 10-40mg daily (or divided bid)a 40mg 24hr Lisinopril 10mg 2.5-10mg 10-40mg daily 80mg 24hr Perindopril 2mg 2-4mg 4-8mg daily 8mg 24hr Quinapril 10mg 5-10mg 10-20mg dailya 40mg 24hr Ramipril 2.5mg 1.25mg-2.5mg 2.5-10mg daily (or divided bid)a 20mg ~24hr a: Some patients may experience a diminished antihypertensive effect toward the end of a 24-hour dosing interval. -

Angiotensin-Converting Enzyme (ACE) Inhibitors

Angiotensin-Converting Enzyme (ACE) Inhibitors Summary Blood pressure reduction is similar for the ACE inhibitors class, with no clinically meaningful differences between agents. Side effects are infrequent with ACE inhibitors, and are usually mild in severity; the most commonly occurring include cough and hypotension. Captopril and lisinopril do not require hepatic conversion to active metabolites and may be preferred in patients with severe hepatic impairment. Captopril differs from other oral ACE inhibitors in its rapid onset and shorter duration of action, which requires it to be given 2-3 times per day; enalaprilat, an injectable ACE inhibitor also has a rapid onset and shorter duration of action. Pharmacology Angiotensin Converting Enzyme Inhibitors (ACE inhibitors) block the conversion of angiotensin I to angiotensin II through competitive inhibition of the angiotensin converting enzyme. Angiotensin is formed via the renin-angiotensin-aldosterone system (RAAS), an enzymatic cascade that leads to the proteolytic cleavage of angiotensin I by ACEs to angiotensin II. RAAS impacts cardiovascular, renal and adrenal functions via the regulation of systemic blood pressure and electrolyte and fluid balance. Reduction in plasma levels of angiotensin II, a potent vasoconstrictor and negative feedback mediator for renin activity, by ACE inhibitors leads to increased plasma renin activity and decreased blood pressure, vasopressin secretion, sympathetic activation and cell growth. Decreases in plasma angiotensin II levels also results in a reduction in aldosterone secretion, with a subsequent decrease in sodium and water retention.[51035][51036][50907][51037][24005] ACE is found in both the plasma and tissue, but the concentration appears to be greater in tissue (primarily vascular endothelial cells, but also present in other organs including the heart). -

Hyponatremia Induced by Angiotensin Converting Enzyme Inhibitors and Angiotensin

DOI: 10.7860/JCDR/2018/31983.11754 Original Article Hyponatremia Induced by Angiotensin Converting Enzyme Inhibitors and Angiotensin Pharmacology Section Receptor Blockers-A Pilot Study S BHUVANESHWARI1, PRAKASH VEL SANKHYA SAROJ2, D VIJAYA3, M SABARI SOWMYA4, R SENTHIL KUMAR5 ABSTRACT Results: Among all, 48% (24 out of 50) of the study population Introduction: Hyponatremia, serum sodium <135 mmol/L, can administered with ACEI and ARB developed hyponatremia. result in neurological manifestation in acute cases, may lead Predisposition to develop hyponatremia was high in males to seizures and coma. Angiotensin Converting Enzyme Inhibitor compared to females. Incidence of hyponatremia was 62.5% (10 (ACEI) and Angiotensin II Receptor Blockers (ARB) are drugs out of 16) in the age group of 56-75 years. Though, incidence of that have been commonly prescribed for the treatment of hyponatremia was 54.5% (18 out of 33) in ACEI group compared hypertension and cardiac diseases. It has become important to 35.2% (6 out of 17) in ARB group, but it was not statistically to evaluate and investigate the incidence of hyponatremia on significant. The study also revealed that metosartan had a higher consumption of these drugs. association with hyponatremia compared to other drugs. Aim: To determine the susceptibility of patients on ACEI and Conclusion: Hyponatremia was induced in nearly 50% of ARB to hyponatremia and to ascertain the drug producing patients taking ACEI and ARB. The incidence of hyponatremia notable hyponatremia among ACEI and ARB. among patients on these two drugs did not show statistical variation. Metosartan showed a higher incidence of Materials and Methods: The study was conducted in a tertiary hyponatremia compared to enalapril, ramipril, captopril, care hospital. -

Zestril® (Lisinopril) Tablets Label

HIGHLIGHTS OF PRESCRIBING INFORMATION • Hypersensitivity (4) These highlights do not include all the information needed to use • Co-administration of aliskiren with Zestril in patients with diabetes (4, ZESTRIL safely and effectively. See full prescribing information for 7.4) ZESTRIL ----------------------- WARNINGS AND PRECAUTIONS --------------------- Zestril® (lisinopril) tablets, for oral use Initial U.S. Approval: 1988 • Angioedema: Discontinue Zestril, provide appropriate therapy and monitor until resolved (5.2) WARNING: FETAL TOXICITY • Renal impairment: Monitor renal function periodically (5.3) See full prescribing information for complete boxed warning. • Hypotension: Patients with other heart or renal diseases have increased • When pregnancy is detected, discontinue Zestril as soon as possible. risk, monitor blood pressure after initiation (5.4) (5.1) • Hyperkalemia: Monitor serum potassium periodically (5.5) • Drugs that act directly on the rennin-angiotensin system can cause • injury and death to the developing fetus. (5.1) Cholestatic jaundice and hepatic failure: Monitor for jaundice or signs of liver failure (5.6) ------------------------------ ADVERSE REACTIONS ---------------------------- --------------------------- INDICATIONS AND USAGE -------------------------- Common adverse reactions (events 2% greater than placebo) by use: Zestril is an angiotensin converting enzyme (ACE) inhibitor indicated for: • Hypertension: headache, dizziness and cough (6.1) • Treatment of hypertension in adults and pediatric patients 6 years of age • Heart Failure: hypotension and chest pain (6.1) and older (1.1) • Acute Myocardial Infarction: hypotension (6.1) • Adjunct therapy for heart failure (1.2) To report SUSPECTED ADVERSE REACTIONS, contact AstraZeneca • Treatment of Acute Myocardial Infarction (1.3) Pharmaceuticals LP at 1-800-236-9933 or FDA at 1-800-FDA-1088 or ---------------------- DOSAGE AND ADMINISTRATION --------------------- www.fda.gov/medwatch. -

Lisinopril (Ethics) Lisinopril Tablets 5 Mg, 10 Mg, 20 Mg

New Zealand Data Sheet Lisinopril (Ethics) Lisinopril Tablets 5 mg, 10 mg, 20 mg 1. NAME OF THE MEDICINAL PRODUCT LISINOPRIL (Ethics) 5 mg, tablet LISINOPRIL (Ethics) 10 mg, tablet LISINOPRIL (Ethics) 20 mg, tablet 2. QUALITATIVE AND QUANTITATIVE COMPOSITION Lisinopril (Ethics) tablets come in three strengths and contain lisinopril dihydrate equivalent to 5 mg, 10 mg or 20 mg lisinopril. 3. PHARMACEUTICAL FORM 5 mg tablet: A light pink coloured, circular, biconvex uncoated tablet. The tablet has a break line and is embossed with ‘5’ on one side and embossed with ‘BL’ on the other side. 10 mg tablet: A light pink coloured, circular, biconvex uncoated tablet. The tablet is embossed with ‘10’ on one side and embossed with ‘BL’ on the other side. 20 mg tablet: A pink, circular, biconvex uncoated tablet. The tablet is embossed with ‘20’ on one side and embossed with ‘BL’ on the other side. Lisinopril dihydrate. The chemical name for lisinopril dihydrate is N-[N-[(1S)-1-carboxy-3- phenylpropyl]-L-lysyl]-L-proline dihydrate. Its structural formula is: C21H31N3O5.2H2O, Molecular weight: 441.53, CAS No.: 83915-83-7 Lisinopril dihydrate is a white to off-white crystalline powder that is soluble in water, sparingly soluble in methanol and practically insoluble in ethanol. A synthetic peptide derivative, lisinopril dihydrate is an oral long acting angiotensin converting enzyme inhibitor. It is a lysine analogue of enalaprilat (active metabolite of enalapril). 4. CLINICAL PARTICULARS 4.1 Therapeutic indications Lisinopril is indicated in the treatment of essential hypertension and in renovascular hypertension. It may be used alone or concomitantly with other classes of antihypertensive agents. -

Switching Ace-Inhibitors

Switching Ace-inhibitors http://www.ksdl.kamsc.org.au/dtp/switching_ace_inhibitors.html Change to → Enalapril Quinapril Ramipril Change from ↓ (Once daily dosing) (Once daily dosing) (Once daily dosing) Captopril Captopril 12.5mg daily Enalapril 2.5mg1 Quinapril 2.5mg Ramipril 1.25mg Captopril 25mg daily Enalapril 5mg1 Quinapril 5mg Ramipril 1.25-2.5mg Captopril 50mg daily Enalapril 7.5mg1 Quinapril 10mg Ramipril 2.5-5mg Captopril 100mg daily Enalapril 20mg1 Quinapril 20mg Ramipril 5-10mg2 Captopril 150mg daily Enalapril 40mg Quinapril 40mg Ramipril 10mg Fosinopril Fosinopril 5mg daily Enalapril 5mg Quinapril 5mg Ramipril 1.25mg Fosinopril 10mg daily Enalapril 10mg Quinapril 10mg Ramipril 2.5mg Fosinopril 20mg daily Enalapril 20mg Quinapril 20mg Ramipril 5mg Fosinopril 40mg daily Enalapril 40mg Quinapril 40mg Ramipril 10mg Lisinopril Lisinopril 5mg daily Enalapril 5mg Quinapril 5mg Ramipril 1.25mg Lisinopril 10mg daily Enalapril 10mg Quinapril 10mg Ramipril 2.5mg Lisinopril 20mg daily Enalapril 20mg Quinapril 20mg Ramipril 5mg Lisinopril 40mg Enalapril 40mg Quinapril 40mg Ramipril 10mg Perindopril Perindopril 2mg daily Enalapril 5-10mg Quinapril 5-10mg Ramipril 2.5mg Perindopril 4mg daily Enalapril 10mg-20mg Quinapril 10mg-20mg Ramipril 5mg Perindopril 8mg daily Enalapril 20-40mg Quinapril 20-40mg Ramipril 10mg Trandolapril Trandolapril 0.5mg d Enalapril 5mg Quinapril 5mg Ramipril 1.25mg Trandolapril 1mg daily Enalapril 10mg Quinapril 10mg Ramipril 2.5mg Trandolapril 2mg daily Enalapril 20mg Quinapril 20mg Ramipril 5mg Trandolapril 4mg daily Enalapril 40mg Quinapril 40mg Ramipril 10mg There are few studies comparing equivalent doses of ACE-inhibitors, for specific indications. Therefore, the above recommendations are based on clinical experiences and are not specific for any indication. -

ACE2 As a Therapeutic Target for COVID-19; Its Role in Infectious Processes and Regulation by Modulators of the RAAS System

Journal of Clinical Medicine Review ACE2 as a Therapeutic Target for COVID-19; Its Role in Infectious Processes and Regulation by Modulators of the RAAS System Veronique Michaud 1,2, Malavika Deodhar 1, Meghan Arwood 1, Sweilem B Al Rihani 1, Pamela Dow 1 and Jacques Turgeon 1,2,* 1 Tabula Rasa HealthCare Precision Pharmacotherapy Research & Development Institute, Orlando, FL 32827, USA; [email protected] (V.M.); [email protected] (M.D.); [email protected] (M.A.); [email protected] (S.B.A.R.); [email protected] (P.D.) 2 Faculty of Pharmacy, Université de Montréal, Montreal, QC H3C 3J7, Canada * Correspondence: [email protected]; Tel.: +856-938-8793 Received: 11 June 2020; Accepted: 2 July 2020; Published: 3 July 2020 Abstract: Angiotensin converting enzyme 2 (ACE2) is the recognized host cell receptor responsible for mediating infection by severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2). ACE2 bound to tissue facilitates infectivity of SARS-CoV-2; thus, one could argue that decreasing ACE2 tissue expression would be beneficial. However, ACE2 catalytic activity towards angiotensin I (Ang I) and II (Ang II) mitigates deleterious effects associated with activation of the renin-angiotensin-aldosterone system (RAAS) on several organs, including a pro-inflammatory status. At the tissue level, SARS-CoV-2 (a) binds to ACE2, leading to its internalization, and (b) favors ACE2 cleavage to form soluble ACE2: these actions result in decreased ACE2 tissue levels. Preserving tissue ACE2 activity while preventing ACE2 shredding is expected to circumvent unrestrained inflammatory response. Concerns have been raised around RAAS modulators and their effects on ACE2 expression or catalytic activity. -

Incidence of Adverse Events with Telmisartan Compared with ACE Inhibitors: Evidence from a Pooled Analysis of Clinical Trials

Patient Preference and Adherence Dovepress open access to scientific and medical research Open Access Full Text Article ORigiNAL RESEARCH Incidence of adverse events with telmisartan compared with ACE inhibitors: evidence from a pooled analysis of clinical trials Giuseppe Mancia1 Abstract: Telmisartan is indicated for the prevention of cardiovascular events in high-risk Helmut Schumacher2 patients, based on comparable efficacy to the angiotensin-converting enzyme (ACE) inhibi- tor, ramipril, in the ONgoing Telmisartan Alone and in combination with Ramipril Global 1Universita degli Studi Milano-Bicocca, Ospedale San Gerardo di Monza, Endpoint Trial (ONTARGET®) trial. However, tolerability must be considered when selecting Milan, Italy; 2Boehringer Ingelheim treatments. This analysis compared the tolerability of telmisartan and ACE inhibitors using Pharma GmbH and Co KG, Ingelheim, Germany data pooled from 12 comparative, randomized studies involving 2564 telmisartan-treated patients and 2144 receiving ACE inhibitors (enalapril, lisinopril, or ramipril). Incidence rates of adverse events for the combined ACE inhibitor treatments and for telmisartan were similar (42.8% vs 43.9%, respectively) as were the rates of serious adverse events (1.8% vs 1.7% for For personal use only. telmisartan, respectively). Patients receiving ACE inhibitors had more cough (8.6% vs 2.6% with telmisartan, P , 0.0001). Results were similar irrespective of age, gender, or ethnicity. The adverse event of angioedema was observed in four patients (0.2%) receiving ACE inhibitors versus none with telmisartan (P = 0.043). There were small, numerical differences in serious adverse events. A total of 107 patients (5.0%) receiving ACE inhibitors and 93 patients (3.6%) receiving telmisartan discontinued treatment because of adverse events (P = 0.021); of these, 32.7% and 5.4%, respectively, were discontinuations due to cough (relative risk reduction of 88% [P , 0.0001] with telmisartan). -

Angiotensin Modulators: ACE Inhibitors and Direct Renin Inhibitors Review 10/09/2008

Angiotensin Modulators: ACE Inhibitors and Direct Renin Inhibitors Review 10/09/2008 Copyright © 2004 - 2008 by Provider Synergies, L.L.C. All rights reserved. Printed in the United States of America. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, digital scanning, or via any information storage and retrieval system without the express written consent of Provider Synergies, L.L.C. All requests for permission should be mailed to: Attention: Copyright Administrator Intellectual Property Department Provider Synergies, L.L.C. 5181 Natorp Blvd., Suite 205 Mason, Ohio 45040 The materials contained herein represent the opinions of the collective authors and editors and should not be construed to be the official representation of any professional organization or group, any state Pharmacy and Therapeutics committee, any state Medicaid Agency, or any other clinical committee. This material is not intended to be relied upon as medical advice for specific medical cases and nothing contained herein should be relied upon by any patient, medical professional or layperson seeking information about a specific course of treatment for a specific medical condition. All readers of this material are responsible for independently obtaining medical advice and guidance from their own physician and/or other medical professional in regard to the best course of treatment for their specific medical condition. This publication, inclusive of all forms contained herein, is intended to be educational in nature and is intended to be used for informational purposes only. Comments and suggestions may be sent to [email protected].