Joseph Haydn, String Quartet in G Major Op

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A Comparative Analysis of the Six Duets for Violin and Viola by Michael Haydn and Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart

A COMPARATIVE ANALYSIS OF THE SIX DUETS FOR VIOLIN AND VIOLA BY MICHAEL HAYDN AND WOLFGANG AMADEUS MOZART by Euna Na Submitted to the faculty of the Jacobs School of Music in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree, Doctor of Music Indiana University May 2021 Accepted by the faculty of the Indiana University Jacobs School of Music, in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree Doctor of Music Doctoral Committee ______________________________________ Frank Samarotto, Research Director ______________________________________ Mark Kaplan, Chair ______________________________________ Emilio Colón ______________________________________ Kevork Mardirossian April 30, 2021 ii I dedicate this dissertation to the memory of my mentor Professor Ik-Hwan Bae, a devoted musician and educator. iii Table of Contents Table of Contents ............................................................................................................................ iv List of Examples .............................................................................................................................. v List of Tables .................................................................................................................................. vii Introduction ...................................................................................................................................... 1 Chapter 1: The Unaccompanied Instrumental Duet... ................................................................... 3 A General Overview -

What Handel Taught the Viennese About the Trombone

291 What Handel Taught the Viennese about the Trombone David M. Guion Vienna became the musical capital of the world in the late eighteenth century, largely because its composers so successfully adapted and blended the best of the various national styles: German, Italian, French, and, yes, English. Handel’s oratorios were well known to the Viennese and very influential.1 His influence extended even to the way most of the greatest of them wrote trombone parts. It is well known that Viennese composers used the trombone extensively at a time when it was little used elsewhere in the world. While Fux, Caldara, and their contemporaries were using the trombone not only routinely to double the chorus in their liturgical music and sacred dramas, but also frequently as a solo instrument, composers elsewhere used it sparingly if at all. The trombone was virtually unknown in France. It had disappeared from German courts and was no longer automatically used by composers working in German towns. J.S. Bach used the trombone in only fifteen of his more than 200 extant cantatas. Trombonists were on the payroll of San Petronio in Bologna as late as 1729, apparently longer than in most major Italian churches, and in the town band (Concerto Palatino) until 1779. But they were available in England only between about 1738 and 1741. Handel called for them in Saul and Israel in Egypt. It is my contention that the influence of these two oratorios on Gluck and Haydn changed the way Viennese composers wrote trombone parts. Fux, Caldara, and the generations that followed used trombones only in church music and oratorios. -

Quartet Dimensions

concert program ii: Quartet Dimensions JOHANN SEBASTIAN BACH (1685–1750)! July 21 WOLFGANG AMADEUS MOZART (1756–1791) Sunday, July 21, 6:00 p.m., The Center for Performing Arts Fugue in E-flat Major, BWV 876, and Fugue in d minor, BWV 877, from at Menlo-Atherton Das wohltemperierte Klavier; arr. String Quartets nos. 7 and 8, K. 405 JOSEPH HAYDN (1732–1809) PROGRAM OVERVIEW String Quartet in d minor, op. 76, no. 2, Quinten (1796) The string quartet medium, arguably the spinal column of the Allegro chamber music literature, did not exist in Bach’s lifetime. Yet Andante o più tosto allegretto Minuetto: Allegro ma non troppo even here, Bach’s legacy is inescapable. The fugues of his semi- Finale: Vivace assai nal The Well-Tempered Clavier inspired no less a genius than Danish String Quartet: Frederik Øland, Rune Tonsgaard Sørensen, violins; Asbjørn Nørgaard, viola; Mozart, who arranged a set of them for string quartet. The influ- Fredrik Schøyen Sjölin, cello ence of Bach’s architectural mastery permeates the ingenious DMITRY SHOSTAKOVICH (1906–1975) Quinten Quartet of Joseph Haydn, the father of the modern Piano Quintet in g minor, op. 57 (1940) string quartet, and even Dmitry Shostakovich’s Piano Quintet, Prelude composed nearly two hundred years after Bach’s death. The Fugue Scherzo centerpiece of Beethoven’s Opus 132—the Heiliger Dankgesang Intermezzo CONCERT PROGRAMSCONCERT eines Genesenen an die Gottheit (“A Convalescent’s Holy Song Finale PROGRAMSCONCERT of Thanksgiving to the Divinity”)—recalls another Bachian signa- Gilbert Kalish, piano; Danish String Quartet: Frederik Øland, Rune Tonsgaard Sørensen, violins; ture: the Baroque master’s sacred chorales. -

The Compositional Influence of Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart on Ludwig Van Beethoven’S Early Period Works

Portland State University PDXScholar Young Historians Conference Young Historians Conference 2018 Apr 18th, 12:30 PM - 1:45 PM The Compositional Influence of olfW gang Amadeus Mozart on Ludwig van Beethoven’s Early Period Works Mary L. Krebs Clackamas High School Follow this and additional works at: https://pdxscholar.library.pdx.edu/younghistorians Part of the Musicology Commons Let us know how access to this document benefits ou.y Krebs, Mary L., "The Compositional Influence of olfW gang Amadeus Mozart on Ludwig van Beethoven’s Early Period Works" (2018). Young Historians Conference. 7. https://pdxscholar.library.pdx.edu/younghistorians/2018/oralpres/7 This Event is brought to you for free and open access. It has been accepted for inclusion in Young Historians Conference by an authorized administrator of PDXScholar. Please contact us if we can make this document more accessible: [email protected]. THE COMPOSITIONAL INFLUENCE OF WOLFGANG AMADEUS MOZART ON LUDWIG VAN BEETHOVEN’S EARLY PERIOD WORKS Mary Krebs Honors Western Civilization Humanities March 19, 2018 1 Imagine having the opportunity to spend a couple years with your favorite celebrity, only to meet them once and then receiving a phone call from a relative saying your mother was about to die. You would be devastated, being prevented from spending time with your idol because you needed to go care for your sick and dying mother; it would feel as if both your dream and your reality were shattered. This is the exact situation the pianist Ludwig van Beethoven found himself in when he traveled to Vienna in hopes of receiving lessons from his role model, Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart. -

Franz Joseph Haydn (1732-1809)

Composer Fact Sheets Franz Joseph Haydn (1732-1809) FAST FACTS • Learned music as a choirboy in Vienna • Dismissed from the choir for playing a practical joke on another choir member • Wrote, performed, and organized music and events for Prince Paul Anton Esterházy • Is known for his sense of humor that is very clear in his music Born: 1732 (Rohrau, Austria) Died: 1809 (Vienna, Austria) Joseph Haydn began his long musical career in St. Stephen’s Cathedral in Vienna, where he successfully auditioned into the choir. In the early 1700s, choirboys received a well-rounded education, so Haydn became proficient at singing, harpsichord, and violin. When he turned 17, his voice changed, so he left the cathedral choir to study music even further, realizing that he had received little training in the fundamentals of music. He studied and mastered music theory, the music of other composers, and took music composition lessons from a famous Italian composer and teacher. Haydn is also rumored to have been dismissed due to a practical joke he played on one of the other members of the choir. After his departure, Haydn struggled to support himself through part-time teaching and even street- serenading. He also performed freelance work for the chapel in Vienna, and filled in as an extra musician at balls that were given for orphaned children. Haydn began to gain a reputation, however, through his independent music studies and performing career. In 1761, Haydn entered the service of Prince Paul Anton Esterházy in Hungary. Haydn was required to compose music at a rapid pace, and to perform his works in concerts weekly, and to assist with chamber music concerts that took place nearly every day. -

The Classical Period (1720-1815), Music: 5635.793

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 096 203 SO 007 735 AUTHOR Pearl, Jesse; Carter, Raymond TITLE Music Listening--The Classical Period (1720-1815), Music: 5635.793. INSTITUTION Dade County Public Schools, Miami, Fla. PUB DATE 72 NOTE 42p.; An Authorized Course of Instruction for the Quinmester Program; SO 007 734-737 are related documents PS PRICE MP-$0.75 HC-$1.85 PLUS POSTAGE DESCRIPTORS *Aesthetic Education; Course Content; Course Objectives; Curriculum Guides; *Listening Habits; *Music Appreciation; *Music Education; Mucic Techniques; Opera; Secondary Grades; Teaching Techniques; *Vocal Music IDENTIFIERS Classical Period; Instrumental Music; *Quinmester Program ABSTRACT This 9-week, Quinmester course of study is designed to teach the principal types of vocal, instrumental, and operatic compositions of the classical period through listening to the styles of different composers and acquiring recognition of their works, as well as through developing fastidious listening habits. The course is intended for those interested in music history or those who have participated in the performing arts. Course objectives in listening and musicianship are listed. Course content is delineated for use by the instructor according to historical background, musical characteristics, instrumental music, 18th century opera, and contributions of the great masters of the period. Seven units are provided with suggested music for class singing. resources for student and teacher, and suggestions for assessment. (JH) US DEPARTMENT OP HEALTH EDUCATION I MIME NATIONAL INSTITUTE -

FRANZ JOSEPH HAYDN (1732–1809) Symphony No

FRI MAY 19 — 11 A.M. FRANZ JOSEPH HAYDN (1732–1809) Symphony No. 39 (1765) Symphony no. 39 in G minor was described as Sturm und Drang; a term taken from a literary movement named after a play of the same name by Friedrich Maximilian Klinger. The musical language is intensely expressive and full of extreme contrasts. James Webster describes the works of this period as “longer, more passionate, and more daring” and “proto-Romantic.” LISTEN FOR: 1. Allegro assai After a nervous first four measures, there’s a grand pause before we move on, heightening the tension and adding to the sense of unease. Can you hear why this movement was associated with Sturm und Drang? 2. Andante A.P. Brown describes this movement as an elegant, “ingratiating little waltz” for Recommended Recording: strings. It features a lot of rhythmic variation of the main themes, as well as a lot of strong Haydn: Symphonies Volume 5, contrasts in dynamics—which help tie this to the other Sturm und Drang movements. The Academy of Ancient Music, Christopher Hogwood, conducting 3. Menuet & Trio Another study in contrasts: a minor-keyed minuet contrasts with a bright trio in major, featuring high notes for the first horn. 4. Finale A true Sturm und Drang close to the symphony. It opens with a tremolando string accompaniment—quick, repeated notes that seem to tremble and shimmer. GYÖRGY LIGETI (1923–2006) Piano Concerto (1988) The piece was commissioned for pianist Anthony di Bonaventura, who wrote: “When it arrived, I just couldn’t decipher it.” The composer’s autograph score is incredibly dense, with thousands of notes and accidentals crammed into the tiniest spaces. -

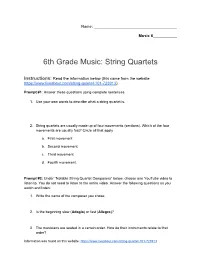

6Th Grade Music: String Quartets

Name: ______________________________________ Music 6___________ 6th Grade Music: String Quartets Instructions: Read the information below (this came from the website https://www.liveabout.com/string-quartet-101-723913). Prompt #1: Answer these questions using complete sentences. 1. Use your own words to describe what a string quartet is. 2. String quartets are usually made up of four movements (sections). Which of the four movements are usually fast? Circle all that apply a. First movement b. Second movement c. Third movement d. Fourth movement. Prompt #2: Under “Notable String Quartet Composers” below, choose one YouTube video to listen to. You do not need to listen to the entire video. Answer the following questions as you watch and listen: 1. Write the name of the composer you chose. 2. Is the beginning slow (Adagio) or fast (Allegro)? 3. The musicians are seated in a certain order. How do their instruments relate to that order? Information was found on this website: https://www.liveabout.com/string-quartet-101-723913 4. How do the musicians respond to each other while playing? Prompt #3: Under Modern String Quartet Music, find the Love Story quartet by Taylor Swift. Listen to it as you answer using complete sentences. 1. Which instrument is plucking at the beginning of the piece? (If you forgot, violins are the smallest instrument, violas are a little bigger, cellos are bigger and lean on the floor). 2. Reflect on how this version of Love Story is different from Taylor Swift’s original song. How would you describe the differences? What does this version communicate? Information was found on this website: https://www.liveabout.com/string-quartet-101-723913 String Quartet 101 All You Need to Know About the String Quartet The Jerusalem Quartet, a string quartet made of members (from left) Alexander Pavlovsky, Sergei Bresler, Kyril Zlontnikov and Ori Kam, perform Brahms’s String Quartet in A minor at the 92nd Street Y on Saturday night, October 25, 2014. -

Haydn and Beethoven

23 Season 2018-2019 Thursday, February 28, at 7:30 The Philadelphia Orchestra Friday, March 1, at 2:00 Saturday, March 2, at 8:00 Nathalie Stutzmann Conductor Benjamin Grosvenor Piano Haydn Symphony No. 94 in G major (“Surprise”) I. Adagio cantabile—Vivace assai II. Andante III. Menuetto: Allegro molto IV. Allegro di molto Beethoven Piano Concerto No. 1 in C major, Op. 15 I. Allegro con brio II. Largo III. Rondo: Allegro Intermission Beethoven Symphony No. 4 in B-flat major, Op. 60 I. Adagio—Allegro vivace II. Adagio III. Allegro vivace IV. Allegro ma non troppo This program runs approximately 2 hours. Philadelphia Orchestra concerts are broadcast on WRTI 90.1 FM on Sunday afternoons at 1 PM, and are repeated on Monday evenings at 7 PM on WRTI HD 2. Visit www.wrti.org to listen live or for more details. PO Book 27.indd 23 2/20/19 11:31 AM 24 PO Book 27.indd 24 2/20/19 11:31 AM 25 The Philadelphia Orchestra Jessica Griffin The Philadelphia Orchestra Philadelphia is home and orchestra, and maximizes is one of the preeminent the Orchestra continues impact through Research. orchestras in the world, to discover new and The Orchestra’s award- renowned for its distinctive inventive ways to nurture winning Collaborative sound, desired for its its relationship with its Learning programs engage keen ability to capture the loyal patrons at its home over 50,000 students, hearts and imaginations of in the Kimmel Center, families, and community audiences, and admired for and also with those who members through programs a legacy of imagination and enjoy the Orchestra’s area such as PlayINs, side-by- innovation on and off the performances at the Mann sides, PopUP concerts, concert stage. -

Franz Joseph Haydn

Press Conference with Franz Joseph Haydn Charles Gibson: Good evening from ABC news. We have just learned that the famous composer of the Classical era, Franz Joseph Haydn, has suddenly appeared at an elementary school in North Carolina. It’s not clear how he has come from the 1700s to the year 2005. He is holding a press conference with members of the press from all over the world. ABC news: Welcome to the United States. Have you come to give a concert? Haydn: If I’m invited to play, I would be glad to, but I’d rather conduct one of my symphonies. NBC news: Which symphony would you like to conduct? Haydn: That’s a good question. I might enjoy conducting one of my “London” symphonies or the Surprise symphony. (The) Creation was probably my greatest work though. The Sun Journal: Is that a symphony too? Haydn: Oh, no. That is an oratorio. News and Observer: Remind us again please. What is an oratorio? Haydn: It’s sort of like a play or an opera, but there are no costumes, no scenery, and no dramatic acting. The whole story is sung by a chorus, solo singers, and small groups of singers. Many oratorios are stories from the Bible, like my Creation oratorio. Wall Street Journal: When and where were you born? Haydn: In 1732 in Austria. Chicago Tribune: What language do you mainly speak? Haydn: German is my first language, but I’m doing my best to speak English to you today. New York Times: Is it true that you are called the “father of the symphony?” Haydn: I’ve heard that. -

PROGRAM NOTES Joseph Haydn Cello Concerto in C Major, Hob

PROGRAM NOTES by Phillip Huscher Joseph Haydn Born March 31, 1732, Rohrau, Austria. Died May 31, 1809, Vienna, Austria. Cello Concerto in C Major, Hob. VIIb:1 Haydn composed this cello concerto in C major between 1761 and 1765. The date of the first performance is not known. The score was lost during the composer’s lifetime and only rediscovered in 1961. It was performed on May 19, 1962, in Prague, by cellist Miloš Sádlo, with Charles Mackerras conducting the Czech Radio Symphony. The orchestra consists of two oboes, two horns, and strings. Performance time is approximately twenty-five minutes. The Chicago Symphony Orchestra’s first subscription concert performances of Haydn’s Cello Concerto in C major were given at Orchestra Hall on December 3 and 4, 1964, with János Starker as soloist and Jean Martinon conducting. Our most recent subscription concert performances were given on March 9, 10, 11, and 14, 1989, with Natasha Gutman as soloist and Christopher Keene conducting. Our most recent performance was given on a musicians’ pension fund concert on April 23, 2004, with Mstislav Rostropovich as soloist and William Eddins conducting. The Orchestra first performed this concerto at the Ravinia Festival on July 15, 1972, with János Starker as soloist and István Kertész conducting, and most recently on August 6, 2006, with Yo-Yo Ma as soloist and Miguel Harth-Bedoya conducting. Until 1961, there was just one cello concerto, in D major, by Haydn. It was long treasured by audiences and cellists alike as the single work of its kind from the great Viennese classical triumvirate—neither Mozart nor Beethoven wrote cello concertos. -

Ottoman Influences on European Music, Part 2

Ottoman influences on European music, part 2 A. Yunus Gencer Introduction This is a continuation of the essay entitled Ottoman influences on Euro- pean music in CMR 10, which briefly examines the history and charac- teristics of Turkish music and focuses on the influence of the Ottomans on European music to the mid-18th century. This second part covers the period from the mid-18th to the early 20th century. During this time, there was a crescendo, followed by a decrescendo, in the frequency and inten- sity of Ottoman-related concepts being utilised by European composers, with a climax occurring in the works of Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart (1756- 91). After Mozart’s death, as Europeans came into contact with various other ‘exotic’ cultures, and as Ottoman power declined further in the 19th century, Ottomania slowly but steadily died away. As it was dying, a reverse influence began, this time Europe being the influencer, and the ‘eternal state’ being the influenced. The reigns of reforming sultans such as Mahmud II (r. 1808-39) and Abdülaziz (r. 1861-76) saw increas- ing interest in European culture and music, as well as the reforming of the military bands (Janissary mehteran), which were the main element that had influenced European composers in the first place. Following the collapse of the empire, the succeeding Turkish Republic made consider- able efforts to Westernise the music scene in the country. It not only founded new conservatoires and orchestras solely devoted to teaching and playing European classical music, but went so far as to forbid Turk- ish classical and folk music education in its music institutions from 1926 to 1976.