Information to Users

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Regional Municipal Planning Strategy

Regional Municipal Planning Strategy OCTOBER 2014 Regional Municipal Planning Strategy I HEREBY CERTIFY that this is a true copy of the Regional Municipal Planning Strategy which was duly passed by a majority vote of the whole Regional Council of Halifax Regional Municipality held on the 25th day of June, 2014, and approved by the Minister of Municipal Affairs on October 18, 2014, which includes all amendments thereto which have been adopted by the Halifax Regional Municipality and are in effect as of the 05th day of June, 2021. GIVEN UNDER THE HAND of the Municipal Clerk and under the corporate seal of the Municipality this _____ day of ____________________, 20___. ____________________________ Municipal Clerk TABLE OF CONTENTS CHAPTER 1: INTRODUCTION .............................................................................................................. 1 1.1 THE FIRST FIVE YEAR PLAN REVIEW ......................................................................................................... 1 1.2 VISION AND PRINCIPLES ................................................................................................................................ 3 1.3 OBJECTIVES ....................................................................................................................................................... 3 1.4 HRM: FROM PAST TO PRESENT .................................................................................................................... 7 1.4.1 Settlement in HRM ................................................................................................................................... -

Numerical Simulation of the Howard Street Tunnel Fire

Fire Technology, 42, 273–281, 2006 C 2006 Springer Science + Business Media, LLC. Manufactured in The United States DOI: 10.1007/s10694-006-7506-9 Numerical Simulation of the Howard Street Tunnel Fire Kevin McGrattan and Anthony Hamins, National Institute of Standards and Technology, Gaithersburg, MD 20899, USA Published online: 24 April 2006 Abstract. The paper presents numerical simulations of a fire in the Howard Street Tunnel, Baltimore, Maryland, following the derailment of a freight train in July, 2001. The model was validated for this application using temperature data collected during a series of fire experi- ments conducted in a decommissioned highway tunnel in West Virginia. The peak predicted temperatures within the Howard Street Tunnel were approximately 1,000◦C (1,800◦F) within the flaming regions, and approximately 500◦C (900◦F) averaged over a length of the tunnel equal to about four rail cars. Key words: fire modeling, Howard Street Tunnel fire, tunnel fires Introduction On July 18, 2001, at 3:08 pm, a 60 car CSX freight train powered by 3 locomotives traveling through the Howard Street Tunnel in Baltimore, Maryland, derailed 11 cars. A fire started shortly after the derailment. The tunnel is 2,650 m (8,700 ft, 1.65 mi) long with a 0.8% upgrade in the section of the tunnel where the fire occurred. There is a single track within the tunnel. Its lower entrance (Camden portal) is near Orioles Park at Camden Yards; its upper entrance is at Mount Royal Station. The train was traveling towards the Mount Royal portal when it derailed. -

Note to Users

NOTE TO USERS This reproduction is the best copy available. UMI ARCHITECTURAL POSTCARDS AND THB COICBPTIOW OP PLACE: lediating Cultural Bxperience Carole Schef fes A thesis in the ~umanitiesProgram Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy at Concordia University Montreal, Quebec, Canada May 1999 Q Carole Scheffer, 1999 National Library Bibliothèque nationale 1+1 of Canada du Canada Acquisitions and Acquisitions et Bibliographie Services services bibliographiques 395 Wellington Street 395, rue Wellington Ottawa ON KI A ON4 Otlawa ON KIA ON4 Canada Canada Your hie Votre reterence Ow lFie Narrtl relermm The author has granted a non- L'auteur a accordé une licence non exclusive licence allowing the exclusive permettant a la National Library of Canada to Bibliothèque nationale du Canada de reproduce, loan, distribute or sel1 reproduire, prêter, distribuer ou copies of this thesis in microform, vendre des copies de cette thèse sous paper or electro'onic formats. la fome de microfiche/filrn, de reproduction sur papier ou sur format électronique. The author retains ownership of the L'auteur conserve la propriété du copyright in hsthesis. Neither the droit d'auteur qui protège cette thèse. thesis nor substantial extracts fiom it Ni la thèse ni des extraits substantiels may be printed or otherwise de celle-ci ne doivent être imprimés reproduced without the author's ou autrement reproduits sans son permission. autorisation. ABSTRACT ARCHITECTURAL POSTCARDS AHD THE COISCEPTIOM OF PLACE: Mediating Cultural Pxpetience Carole Scheffer, Ph.D. Concordia University, 1999 By radically altering accesaibility to architectural images, the postcard has promoted the dissemination of diverse values and ideas that both mediate and are mediated by the cultural experience of architecture and place. -

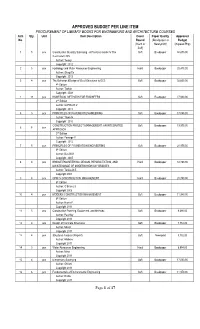

APPROVED BUDGET PER LINE ITEM PROCUREMENT of LIBRARY BOOKS for ENGINEERING and ARCHITECTURE COURSES Item Qty

APPROVED BUDGET PER LINE ITEM PROCUREMENT OF LIBRARY BOOKS FOR ENGINEERING AND ARCHITECTURE COURSES Item Qty. Unit Item Description Cover Paper Quality Approved No. Bound (Bookpaper or Budget (Hard or Newsprint) (in peso/Php) Soft) 1 5 pcs Construction Quantity Surveying - A Practical Guide for The Soft Bookpaper 30,475.00 Contractor's QS Author: Towey Copyright 2012 2 5 pcs Hydrology and Water Resources Engineering Hard Bookpaper 20,475.00 Author: Shagufta Copyright 2013 3 4 pcs The Behavior &Design of Steel Structures to EC3 Soft Bookpaper 30,600.00 4th Edition Author: Trahair Copyright 2008 4 14 pcs NUMERICAL METHODS FOR ENGINEERS Soft Bookpaper 27,930.00 2nd Edition Author: Griffiths D.V. Copyright 2011 5 3 pcs PRINCIPLES OF PAVEMENT ENGINEERING Soft Bookpaper 17,085.00 Author: Thom N. Copyright 2010 CONSTRUCTION PROJECT MANAGEMENT: AN INTEGRATED Soft Bookpaper 19,975.00 6 5 pcs APPROACH 2nd Edition Author: Fewings P. Copyright 2012 7 5 pcs PRINCIPLES OF FOUNDATION ENGINEERING Soft Bookpaper 20,975.00 6th Edition Author: Das B.M. Copyright 2007 8 4 pcs BRIDGE ENGINEERING: DESIGN, REHABILITATION, AND Hard Bookpaper 32,780.00 MAINTENANCE OF MODERN HIGHWAY BRIDGES Author: Tonias D.E. Copyright 2007 9 4 pcs CPM IN CONSTRUCTION MANAGEMENT Hard Bookpaper 28,780.00 6th Edition Author: O’Brien J.J. Copyright 2006 10 4 pcs MODERN CONSTRUCTION MANAGEMENT Soft Bookpaper 11,980.00 6th Edition Author: Harris F. Copyright 2013 11 5 pcs Construction Planning, Equipment, and Methods Soft Bookpaper 9,690.00 Author: Peurifoy Copyright 2011 12 4 pcs -

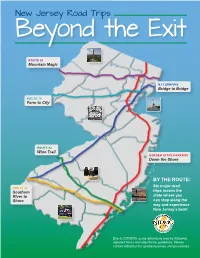

Beyond the Exit

New Jersey Road Trips Beyond the Exit ROUTE 80 Mountain Magic NJ TURNPIKE Bridge to Bridge ROUTE 78 Farm to City ROUTE 42 Wine Trail GARDEN STATE PARKWAY Down the Shore BY THE ROUTE: Six major road ROUTE 40 Southern trips across the River to state where you Shore can stop along the way and experience New Jersey’s best! Due to COVID19, some attractions may be following adjusted hours and attendance guidelines. Please contact attraction for updated policies and procedures. NJ TURNPIKE – Bridge to Bridge 1 PALISADES 8 GROUNDS 9 SIX FLAGS CLIFFS FOR SCULPTURE GREAT ADVENTURE 5 6 1 2 4 3 2 7 10 ADVENTURE NYC SKYLINE PRINCETON AQUARIUM 7 8 9 3 LIBERTY STATE 6 MEADOWLANDS 11 BATTLESHIP PARK/STATUE SPORTS COMPLEX NEW JERSEY 10 OF LIBERTY 11 4 LIBERTY 5 AMERICAN SCIENCE CENTER DREAM 1 PALISADES CLIFFS - The Palisades are among the most dramatic 7 PRINCETON - Princeton is a town in New Jersey, known for the Ivy geologic features in the vicinity of New York City, forming a canyon of the League Princeton University. The campus includes the Collegiate Hudson north of the George Washington Bridge, as well as providing a University Chapel and the broad collection of the Princeton University vista of the Manhattan skyline. They sit in the Newark Basin, a rift basin Art Museum. Other notable sites of the town are the Morven Museum located mostly in New Jersey. & Garden, an 18th-century mansion with period furnishings; Princeton Battlefield State Park, a Revolutionary War site; and the colonial Clarke NYC SKYLINE – Hudson County, NJ offers restaurants and hotels along 2 House Museum which exhibits historic weapons the Hudson River where visitors can view the iconic NYC Skyline – from rooftop dining to walk/ biking promenades. -

RIDING ROUTE 66 - the Chicago to LA Tour & Rally a GUIDED MOTORCYCLE & AUTO TOUR & RALLY DAILY TOUR ITINERARY

RIDING ROUTE 66 - The Chicago to LA Tour & Rally A GUIDED MOTORCYCLE & AUTO TOUR & RALLY DAILY TOUR ITINERARY Friday, August 27 to Saturday, September 11, 2021 Day 1: Friday, August 27: Arrive in Chicago, Illinois The Riding Route 66 - Chicago to LA Tour officially kicks off today! Participants will spend the early part of the day traveling to Chicago and arriving at Willowbrook, IL. Those who will be flying in and need to rent a Harley, or a vehicle, will need to do so in the afternoon. Your ground transportation is your responsibility. All participants/passengers and motorcycles/vehicles will need to be checked in at the Hotel prior to 6:00 p.m. After Check-In participants and/or passengers will be free until we meet for dinner and drinks at 7:30 p.m. to get better acquainted, enjoy dinner/refreshments along with an introductory presentation about pertinent information and features and tips of the Tour from your Tour Guide(s). Day 2: Saturday, August 28: Willowbrook, Illinois to Chicago, Illinois & Return Approximately 85 miles Today is a newly added day to allow those who cannot arrive on Friday to arrive or those interested in visiting downtown Chicago, IL, to do so. Eat at Lou Mitchell’s, travel the Route 66 Loop, visit the End of Route 66 Signpost and the Begin Route 66 Signpost, Grant Park, the Miracle Mile and return down Ogden Ave/Route 66, maybe stop for photos at Henry’s Hot Dogs, Castle Car Wash or Steak n’ Egger ... and enjoy a little Route 66 experience Chicago-style. -

Songs by Title

Karaoke Song Book Songs by Title Title Artist Title Artist #1 Nelly 18 And Life Skid Row #1 Crush Garbage 18 'til I Die Adams, Bryan #Dream Lennon, John 18 Yellow Roses Darin, Bobby (doo Wop) That Thing Parody 19 2000 Gorillaz (I Hate) Everything About You Three Days Grace 19 2000 Gorrilaz (I Would Do) Anything For Love Meatloaf 19 Somethin' Mark Wills (If You're Not In It For Love) I'm Outta Here Twain, Shania 19 Somethin' Wills, Mark (I'm Not Your) Steppin' Stone Monkees, The 19 SOMETHING WILLS,MARK (Now & Then) There's A Fool Such As I Presley, Elvis 192000 Gorillaz (Our Love) Don't Throw It All Away Andy Gibb 1969 Stegall, Keith (Sitting On The) Dock Of The Bay Redding, Otis 1979 Smashing Pumpkins (Theme From) The Monkees Monkees, The 1982 Randy Travis (you Drive Me) Crazy Britney Spears 1982 Travis, Randy (Your Love Has Lifted Me) Higher And Higher Coolidge, Rita 1985 BOWLING FOR SOUP 03 Bonnie & Clyde Jay Z & Beyonce 1985 Bowling For Soup 03 Bonnie & Clyde Jay Z & Beyonce Knowles 1985 BOWLING FOR SOUP '03 Bonnie & Clyde Jay Z & Beyonce Knowles 1985 Bowling For Soup 03 Bonnie And Clyde Jay Z & Beyonce 1999 Prince 1 2 3 Estefan, Gloria 1999 Prince & Revolution 1 Thing Amerie 1999 Wilkinsons, The 1, 2, 3, 4, Sumpin' New Coolio 19Th Nervous Breakdown Rolling Stones, The 1,2 STEP CIARA & M. ELLIOTT 2 Become 1 Jewel 10 Days Late Third Eye Blind 2 Become 1 Spice Girls 10 Min Sorry We've Stopped Taking Requests 2 Become 1 Spice Girls, The 10 Min The Karaoke Show Is Over 2 Become One SPICE GIRLS 10 Min Welcome To Karaoke Show 2 Faced Louise 10 Out Of 10 Louchie Lou 2 Find U Jewel 10 Rounds With Jose Cuervo Byrd, Tracy 2 For The Show Trooper 10 Seconds Down Sugar Ray 2 Legit 2 Quit Hammer, M.C. -

Evaluation of Bridge Inspection and Assessment in Illinois

FINAL REPORT EVALUATION OF BRIDGE INSPECTION AND ASSESSMENT IN ILLINOIS Project IVD-H1, FY 00/01 Report No. ITRC FR 00/01-3 Prepared by Farhad Ansari Ying Bao Sue McNeil Adam Tennant Ming Wang and Laxmana Reddy Rapol Urban Transportation Center University of Illinois at Chicago Chicago, Illinois December 2003 Illinois Transportation Research Center Illinois Department of Transportation ILLINOIS TRANSPORTATION RESEARCH CENTER This research project was sponsored by the State of Illinois, acting by and through its Department of Transportation, according to the terms of the Memorandum of Understanding established with the Illinois Transportation Research Center. The Illinois Transportation Research Center is a joint Public-Private- University cooperative transportation research unit underwritten by the Illinois Department of Transportation. The purpose of the Center is the conduct of research in all modes of transportation to provide the knowledge and technology base to improve the capacity to meet the present and future mobility needs of individuals, industry and commerce of the State of Illinois. Research reports are published throughout the year as research projects are completed. The contents of these reports reflect the views of the authors who are responsible for the facts and the accuracy of the data presented herein. The contents do not necessarily reflect the official views or policies of the Illinois Transportation Research Center or the Illinois Department of Transportation. This report does not constitute a standard, specification, or regulation. Neither the United States Government nor the State of Illinois endorses products or manufacturers. Trade or manufacturers’ names appear in the reports solely because they are considered essential to the object of the reports. -

Designing the Airstream: the Cultural History of Compact Space, Ca. 1920 to the 1960S” a Thesis Submitted to the Kent St

"Designing the Airstream: The Cultural History of Compact Space, ca. 1920 to the 1960s” A thesis submitted to the Kent State University Honors College in partial fulfillment of the requirements for General Honors by Ronald Balas Aug. 6, 2014 Table of Contents Introduction 1 Background 4 Airstream Design and Development 17 Data Visualization 25 Conclusion 34 List of Figures (if any) List of Illustrations (if any) List of Tables (if any) Preface, including acknowledgements, or acknowledgements alone if there is no preface List of Illustrations Model T with tent 10 Covered Wagon (vardos) 17 Diagram of Airstream 23 Diagram of music 25 Levittown 28 Airstream roundup 28 Airstream diagram 29 Girls on train 30 Airstream blueprint 30 Color diagram 31 Floor plan diagram 32 Base camp diagram with photos 33 I would like to thank Dr. Diane Scillia for all of her patience, guidance, and understanding during my commitment to this thesis. I would not have been able to complete this without her and her knowledge. I would also like to thank my wife, Katherine, and my kids for putting up with this ‘folly of going back to school at my age...’ "DESIGNING THE AIRSTREAM: THE CULTURAL HISTORY OF COMPACT SPACE, CA. 1920 TO THE 1960S" INTRO Since 1931, with more than 80 years of war, social, and political changes, there is an industry that began with less than 50 manufacturers, swelled within seven years to more than 400, only to have one company from that time period remain: the Airstream1. To make this even more astounding: the original design never changed. -

Songs by Artist

73K October 2013 Songs by Artist 73K October 2013 Title Title Title +44 2 Chainz & Chris Brown 3 Doors Down When Your Heart Stops Countdown Let Me Go Beating 2 Evisa Live For Today 10 Years Oh La La La Loser Beautiful 2 Live Crew Road I'm On, The Through The Iris Do Wah Diddy Diddy When I'm Gone Wasteland Me So Horny When You're Young 10,000 Maniacs We Want Some P---Y! 3 Doors Down & Bob Seger Because The Night 2 Pac Landing In London Candy Everybody Wants California Love 3 Of A Kind Like The Weather Changes Baby Cakes More Than This Dear Mama 3 Of Hearts These Are The Days How Do You Want It Arizona Rain Trouble Me Thugz Mansion Love Is Enough 100 Proof Aged In Soul Until The End Of Time 30 Seconds To Mars Somebody's Been Sleeping 2 Pac & Eminem Closer To The Edge 10cc One Day At A Time Kill, The Donna 2 Pac & Eric Williams Kings And Queens Dreadlock Holiday Do For Love 311 I'm Mandy 2 Pac & Notorious Big All Mixed Up I'm Not In Love Runnin' Amber Rubber Bullets 2 Pistols & Ray J Beyond The Gray Sky Things We Do For Love, The You Know Me Creatures (For A While) Wall Street Shuffle 2 Pistols & T Pain & Tay Dizm Don't Tread On Me We Do For Love She Got It Down 112 2 Unlimited First Straw Come See Me No Limits Hey You Cupid 20 Fingers I'll Be Here Awhile Dance With Me Short Dick Man Love Song It's Over Now 21 Demands You Wouldn't Believe Only You Give Me A Minute 38 Special Peaches & Cream 21st Century Girls Back Where You Belong Right Here For You 21St Century Girls Caught Up In You U Already Know 3 Colours Red Hold On Loosely 112 & Ludacris Beautiful Day If I'd Been The One Hot & Wet 3 Days Grace Rockin' Into The Night 12 Gauge Home Second Chance Dunkie Butt Just Like You Teacher, Teacher 12 Stones 3 Doors Down Wild Eyed Southern Boys Crash Away From The Sun 3LW Far Away Be Like That I Do (Wanna Get Close To We Are One Behind Those Eyes You) 1910 Fruitgum Co. -

Super Natural Hybrid Strategies for Urban Flood Protection in Coney Island NY

SUPER NATURAL hybrid strategies for urban flood protection in Coney Island NY GEORGES FISCHER MLA Candidate 2017 Rhode Island School of Design A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Master of Landscape Architecture Degree in the Department of Landscape Architecture of the Rhode Island School of Design, Providence, Rhode Island. By Georges Fischer May 30, 2017 Approved by Masters Examination Committee: Scheri Fultineer, Department Head, Landscape Architecture Suzanne Mathew, Primary Thesis Advisor Theodore Hoerr, Secondary Thesis Advisor Contents 6 INTRODUCTION PHASE 1 11 introduction 12 wave diagrams 14 land-sea breezes 17 wave form experiments 20 history and site sections 22 findings and conclusions PHASE 2 26 introduction 28 - 46 case studies 48 kit of parts 50 emotional aspects of sand loss 52 existing site sand retention 54 visualizing volumes of sand 58 findings and conclusions PHASE 3 62 introduction 64 dystopian scenario in twenty years 66 initial concepts 68 site rezoning strategy 70 study model 72 schematic plan 74 alternative scenario in twenty years 76 findings and conclusions CONCLUSIONS 80 final conclusions + bibliography Overview Site How will inundation change the design of city coastlines? This thesis is an In Phase 3, this range of analyses are synthesized to form new hybridized Coney Island has been selected because the highest points are barely 10 feet At that time, Coney Island was a resort for the everyday person. While elites investigation into strategies to mitigate urban flooding from storm surge in coastal edges. This method has yielded new insights into coastal urban above the high tide line. -

Songs by Artist

Sound Master Entertianment Songs by Artist smedenver.com Title Title Title .38 Special 2Pac 4 Him Caught Up In You California Love (Original Version) For Future Generations Hold On Loosely Changes 4 Non Blondes If I'd Been The One Dear Mama What's Up Rockin' Onto The Night Thugz Mansion 4 P.M. Second Chance Until The End Of Time Lay Down Your Love Wild Eyed Southern Boys 2Pac & Eminem Sukiyaki 10 Years One Day At A Time 4 Runner Beautiful 2Pac & Notorious B.I.G. Cain's Blood Through The Iris Runnin' Ripples 100 Proof Aged In Soul 3 Doors Down That Was Him (This Is Now) Somebody's Been Sleeping Away From The Sun 4 Seasons 10000 Maniacs Be Like That Rag Doll Because The Night Citizen Soldier 42nd Street Candy Everybody Wants Duck & Run 42nd Street More Than This Here Without You Lullaby Of Broadway These Are Days It's Not My Time We're In The Money Trouble Me Kryptonite 5 Stairsteps 10CC Landing In London Ooh Child Let Me Be Myself I'm Not In Love 50 Cent We Do For Love Let Me Go 21 Questions 112 Loser Disco Inferno Come See Me Road I'm On When I'm Gone In Da Club Dance With Me P.I.M.P. It's Over Now When You're Young 3 Of Hearts Wanksta Only You What Up Gangsta Arizona Rain Peaches & Cream Window Shopper Love Is Enough Right Here For You 50 Cent & Eminem 112 & Ludacris 30 Seconds To Mars Patiently Waiting Kill Hot & Wet 50 Cent & Nate Dogg 112 & Super Cat 311 21 Questions All Mixed Up Na Na Na 50 Cent & Olivia 12 Gauge Amber Beyond The Grey Sky Best Friend Dunkie Butt 5th Dimension 12 Stones Creatures (For A While) Down Aquarius (Let The Sun Shine In) Far Away First Straw AquariusLet The Sun Shine In 1910 Fruitgum Co.