OFFSHORE MAGAZINE ARTICLE on the MACGREGOR 26 Two Boats

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Accidents ΠSee Anchors/Anchoring Binoculars Boat ΠAccidents

Subject Article Author Issue & Page Accidents – See Boat – Accidents Tow Vehicle – Accidents Trailer – Accidents Advice-See Sailing Stories Anchors/Anchoring Lights Anchor Light Alternative Brandt Spr 91 p33 Cockpit/Anchor Light Christensen Spr 98 p26 Rights Anchoring: A Right or a Privilege Ed Fall 93 p20 Anchoring Charges in Ontario Hodgson Spr 98 p28 Markers The World’s Best Anchor Buoy Christensen Spr 97 p10 Another Anchor Marker Ziliox Sum 97 p23 Shore tie anchoring Reading in the Rain Christensen Spr 99 p6 Summer ’98 Around Lake Huron (Almost) Vanderhulst Spr 99 p19 Storage Me and my Mac 26-Bow Pulpit Anchor Storage Bracket Schmitt Sum 97 p25 Stories & Techniques Dragging Anchor With a Nudist Hodgson Spr 90 p39 Dinghy Mooring Christensen Spr 93 p15 How to Gain Experience Collins Spr 94 p38 A New Slant on Anchoring Collins Fall 94 p38 Blown Away in the Florida Keys McComb Fall 97 p15 From Cleveland to Jurassic Park (and Back) Reichert Spr 98 p15 Reading in the Rain Christensen Spr 99 p6 Unusual Anchors Cove Dwellers Butler Spr 87 p11 Ants-See Pests-Bugs & Critters Batteries – See Electrical Beer – See Liquor Bimini-See Cockpit Binoculars The Bahamas Despite El Nino Kulish Fall 98 p3 Boat – Accidents The Shortest Cruise Cooperman Fall 90 p4 Just One Armadillo Hodgson Fall 90 p32 Chronicles of a Budding Sailor Bradley Spr 94 p80 Sail Safely Arnett Spr 96 p16 Beached Miller, M Sum 97 p11 Prepare for a Fire Emergency Collins Sum 97 p17 Subject Article Author Issue & Page Boat – Bottom Barnacles Bubble, Bubble, Toil and Trouble Hodgson -

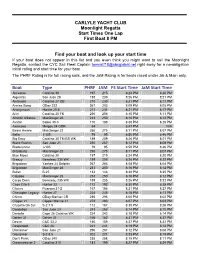

Boat Type PHRF JAM FS Start Time Jam Start Time

CARLYLE YACHT CLUB Moonlight Regatta Start Times One Lap First Boat 8 PM Find your boat and look up your start time If your boat does not appear in this list and you even think you might want to sail the Moonlight Regatta, contact the CYC Sail Fleet Captain [email protected] right away for a no-obligation initial rating and start time for your boat. The PHRF Rating is for full racing sails, and the JaM Rating is for boats raced under Jib & Main only. Boat Type PHRF JAM FS Start Time JaM Start Time Akcestas Catalina 30 197 215 8:24 PM 8:20 PM Algeciras San Juan 28 188 209 8:26 PM 8:21 PM Ambrosia Catalina 27 OB 210 230 8:21 PM 8:17 PM Annies Song ODay 222 267 283 8:09 PM 8:05 PM Anonymous Hunter 25.5 211 231 8:21 PM 8:17 PM Ariel Catalina 25 FK 236 256 8:15 PM 8:11 PM Atlantic Alliance MacGregor 26 233 250 8:16 PM 8:12 PM Avatar Sabre 30-3 170 189 8:30 PM 8:26 PM Axomoxa Melges 24 ODR 94 8:47 PM N/A Beare Amare MacGregor 22 255 275 8:11 PM 8:07 PM Bella J-105 79 95 8:50 PM 8:46 PM Big Easy Catalina 30 TM BS WK 189 209 8:26 PM 8:21 PM Black Rushin San Juan 21 250 267 8:12 PM 8:08 PM Bladerunner J-105 79 95 8:50 PM 8:46 PM Blitzeburg MacGregor 22 255 275 8:11 PM 8:07 PM Blue Moon Catalina 30 197 215 8:24 PM 8:20 PM Breezy Beneteau 235 WK 189 205 8:26 PM 8:22 PM Brigadoon Yankee 24 Dolphin 267 286 8:08 PM 8:04 PM Brigadoon MacGregor 26 233 250 8:16 PM 8:12 PM Bullet B-25 133 148 8:38 PM 8:35 PM Calypso MacGregor 26 233 250 8:16 PM 8:12 PM Carpe Diem Beneteau 235 WK 189 205 8:26 PM 8:22 PM Casa Cita II Hunter 33 172 192 8:30 PM 8:25 -

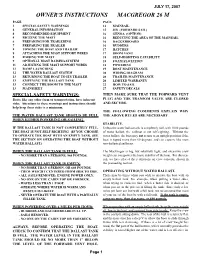

Owner's Instructions Macgregor 26 M

JULY 17, 2007 OWNER’S INSTRUCTIONS MACGREGOR 26 M PAGE PAGE 1 SPECIAL SAFETY WARNINGS 14 MAINSAIL 4 GENERAL INFORMATION 15 JIB (FORWARD SAIL) 4 RECOMMENDED EQUIPMENT 16 GENOA (OPTION) 4 RIGGING THE MAST 16 REDUCING THE AREA OF THE MAINSAIL 6 PREPARING FOR TRAILERING 16 DAGGERBOARD 7 PREPARING THE TRAILER 16 RUDDERS 8 TOWING THE BOAT AND TRAILER 17 HATCHES 8 ATTACHING THE MAST SUPPORT WIRES 17 BOOM VANG 8 RAISING THE MAST 18 SELF-RIGHTING CAPABILITY 9 OPTIONAL MAST RAISING SYSTEM 18 FOAM FLOTATION 11 ADJUSTING THE MAST SUPPORT WIRES 18 POWERING 12 RAMP LAUNCHING 19 BOAT MAINTENANCE 12 THE WATER BALLAST SYSTEM 20 WIRING DIAGRAM 13 RETURNING THE BOAT TO ITS TRAILER 20 TRAILER MAINTENANCE 13 EMPTYING THE BALLAST TANK 20 LIMITED WARRANTY 13 CONNECT THE BOOM TO THE MAST 22 HOW TO SAIL 13 MAINSHEET 27 SAFETY DECALS SPECIAL SAFETY WARNINGS: THEN MAKE SURE THAT THE FORWARD VENT Boats, like any other form of transportation, have inherent PLUG AND THE TRANSOM VALVE ARE CLOSED risks. Attentions to these warnings and instructions should AND SECURE. help keep these risks to a minimum. THE FOLLOWING COMMENTS EXPLAIN WHY THE WATER BALLAST TANK SHOULD BE FULL THE ABOVE RULES ARE NECESSARY. WHEN EITHER POWERING OR SAILING. STABILITY. IF THE BALLAST TANK IS NOT COMPLETELY FULL, Unless the water ballast tank is completely full, with 1000 pounds THE BOAT IS NOT SELF RIGHTING. (IF YOU CHOOSE of water ballast, the sailboat is not self-righting. Without the TO OPERATE THE BOAT WITH AN EMPTY TANK, SEE water ballast, the boat may not return to an upright position if the THE SECTION ON OPERATING THE BOAT WITHOUT boat is tipped more than 60 degrees, and can capsize like most WATER BALLAST.) non-ballasted sailboats. -

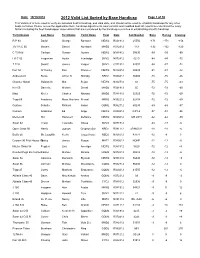

2012 Valid List Sorted by Base Handicap

Date: 10/19/2012 2012 Valid List Sorted by Base Handicap Page 1 of 30 This Valid List is to be used to verify an individual boat's handicap, and valid date, and should not be used to establish handicaps for any other boats not listed. Please review the appilication form, handicap adjustments, boat variants and modified boat list reports to understand the many factors including the fleet handicapper observations that are considered by the handicap committee in establishing a boat's handicap Yacht Design Last Name First Name Yacht Name Fleet Date Sail Number Base Racing Cruising R P 90 David George Rambler NEW2 R021912 25556 -171 -171 -156 J/V I R C 66 Meyers Daniel Numbers MHD2 R012912 119 -132 -132 -120 C T M 66 Carlson Gustav Aurora NEW2 N081412 50095 -99 -99 -90 I R C 52 Fragomen Austin Interlodge SMV2 N072412 5210 -84 -84 -72 T P 52 Swartz James Vesper SMV2 C071912 52007 -84 -87 -72 Farr 50 O' Hanley Ron Privateer NEW2 N072412 50009 -81 -81 -72 Andrews 68 Burke Arthur D Shindig NBD2 R060412 55655 -75 -75 -66 Chantier Naval Goldsmith Mat Sejaa NEW2 N042712 03 -75 -75 -63 Ker 55 Damelio Michael Denali MHD2 R031912 55 -72 -72 -60 Maxi Kiefer Charles Nirvana MHD2 R041812 32323 -72 -72 -60 Tripp 65 Academy Mass Maritime Prevail MRN2 N032212 62408 -72 -72 -60 Custom Schotte Richard Isobel GOM2 R062712 60295 -69 -69 -57 Custom Anderson Ed Angel NEW2 R020312 CAY-2 -57 -51 -36 Merlen 49 Hill Hammett Defiance NEW2 N020812 IVB 4915 -42 -42 -30 Swan 62 Tharp Twanette Glisse SMV2 N071912 -24 -18 -6 Open Class 50 Harris Joseph Gryphon Soloz NBD2 -

Delta Doo Dah: Season of Change, 2015

DELTA DOO DAH 7 At the end of last year's Delta Doo Dah feature story, we promised big changes for 2015, and indeed Delta Doo vorite destination has been Three River Dah 7 was like none other. Heck, even Since this year's Delta Doo Dah Reach. the Delta itself, where change comes retained a strong DIY element, we'll let "This year when we got there I more slowly than it does in the faster- the sailors pick up the tale: thought that it was odd that there were paced Bay Area, does not stand still. no other boats anchored, as it has been Among the changes affecting sailors Itzayana — Beneteau Oceanis 331 typical to see anywhere from 5 to 20 was a salinity dam that blocked the west- Liam Wald & Jane Wong, Santa Cruz others. Luckily we were going in at high ern entrance to False River (a popular "We were part of the Doo Dah again tide, as we found that the depth under shortcut and entrance to Franks Tract this year and had a great time as usual," the 6-ft keel was 1.5-2 feet. The tide was and Bethel Island), and produced strong writes Liam Wald. "We've been going to going to drop more than that, leaving currents in and around Fisherman's Cut. the Delta every year (sometimes twice) us in the mud. In years past there was Besides the new dam, various bridge for the last 10 years or so, and our fa- usually at least 3-4 feet under the keel closings, planned and unplanned, forced sailors to adapt their routes. -

Southern Bay Racing News You Can Use #491 SBRNYCU Is an Independent Weekly Publication of Southern Chesapeake Bay Racing Happenings

Page 1 of 3 Subj: #491 SOUTHERN BAY RACING NEWS YOU CAN USE Date: 5/3/2010 8:34:53 A.M. Eastern Daylight Time From: [email protected] To: [email protected] For additional information contact: Lin McCarthy, (757) 850-4225 Southern Bay Racing News You Can Use #491 SBRNYCU is an independent weekly publication of southern Chesapeake Bay racing happenings. Founded in April, 2000. CCV SPRING SERIES IS A WRAP. SEA STAR, COOL CHANGE, QUICKY, and BLACK WIDOW are fleet winners. Sunday proved perfect for the final two races of the five race series that traditionally opens the season on the southern Bay. A rock solid breeze out of 240 that ranged between 12 and 20 knots was just what the doctor ordered and the fleet of 36 boats made the most of it. The Spring Series (overall) awards will be presented at the CCV Annual Awards Party in early November. Here are the top finishers in each fleet: PHRF A (10 boats racing): 1.Dave Eberwine, Sea Star, J/36; 2.Phil Briggs, Feather, J/36; 3.Christian Schaumloffel, Mirage, Hobie 33; 4.Bob Mosby, Cyrano, Frers 36. PHRF B (13 boats racing): 1.Rusty Burshell, Cool Change, J/30; 2.Bob Archer, Bad Habit, Pearson Flyer; 3.Graham Field, Independence, Islander 36; 4.Chuck Monsees, Rockette, J/29. PHRF C (12 boats racing): 1.Mike Veraldi, Quicky, J/24; 2.Alan & Will Bomar, Roundabout, J/24; 3.Justin Morris, The Hunter, Hunter 26.5; 4.Jonathan Phillips, Fine, Kirby 25. PHRF Non-Spin (7 boats racing): 1.Leo Wardrup, Black Widow, Irwin 38; 2.Don Barfield & Steve Smith, Checko, Macgregor 26; 3.Mitch Doughtie, Old School, S2 7.9. -

PHRF of the Alamo 01-17-2016

PHRF of the Alamo January 17, 2016 Boat Type PHRF Boat Type PHRF Boat Type PHRF Beneteau First 23.5 198-P Columbia 26 229 J-105 ODR 88 Beneteau Oceanis 321 165 Ericson 25 + OB 205 J-105 SD 87 Beneteau Oceanis 323 147 Ericson 28 + SD 187 J-105 SD ODR 94 Beneteau Oceanis 331 148 Extreme Force 25 90-P* Macgregor 26 218 C & C 35-3 122 Hobie 33 ODR 93-P O'Day 27-2 229 Cal 24-3 218 Holder 20 185 O'Day 28 TM / DK 192* Cal 25-1 225 Hunter 25 OB 223 O'Day 30 180 Cal 27-2 IB 207 Hunter 25.5 OB 206 Olson 30 102 Cal 34 174 Hunter 28 186 Precision 23 233 Capri 18 286 Hunter 28.5 180 Precision 28 IB 195-P Capri 26 212 Hunter 33.5 147 Ranger 28 TM 183 Catalina 22 SK / FK 270 Hunter 356 138 Ranger 30 173-P Catalina 25 FK TM 223 Hunter 37.5 Legend 120 S-2 27 IB 186 Catalina 25 WK TM 226 Irwin 31 Citation 171 S-2 7.3 SD 242 Catalina 25 SK 228 J-22 ODR 180 S-2 9.2 C SD 183 Catalina 27 OB 204-P J-24 170 Sabre 362 CB 118 Catalina 27 IB 204-P J-27 126 Seaward 25 270 Catalina 270 199 J-70 117-P Soling ODR 153 Catalina 30 184 J-80 114 Sonar 23 177-P* Catalina 34 WK 157* J-80 ODR 120 Spirit 28 195 Catalina 36 141 J-92 104 Starwind 22 FR 270 Colgate 26 163 J-105 81 Starwind 27 OB 177 VX One 102-P Viper 640 98-P * = Change from 2014 PHRF Rating P = Provisional Rating ODR = One Design Racer PHRF Assumptions: 1) Spinnaker pole length equal to the base of the fore triangle - "J"; 2) Spinnaker maximum width is 180% of "J"; 3) Spinnaker maximum length is 95% of the length of the jib stay; 4) Genoa LP is between 150% and 155% of "J"; 5) The boat is in racing condition; 6) The boat has a folding or feathering prop or an outboard motor; 7) The hull and appendages are unmodified; 8) Multihulls are not to be fleeted with monohulls; 9) All keels and weighted centerboards shall remain down while racing. -

Lake Michigan Devours Its Wounded: Boats and Sailors Cruising Western Lake Superior Minneapolis & Strictly Sail Shows Boatspeed IQ Test

Volume XVIII No. 10 Dec 2007 Lake Michigan Devours Its Wounded: Boats and Sailors Cruising Western Lake Superior Minneapolis & Strictly Sail Shows Boatspeed IQ Test Over 500 New and Used Boats hicag r, C o, ie IL P y v a N 20 08 Come Sail Away! Strictly Sail® Chicago January 31–February 3, 2008 • Navy Pier, Chicago The Midwest’s only all-sail boat show! Skip the lines! For advance tickets and show details visit StrictlySailChicago.com or call 800.817.7245 Northland Yachts Celebrating 34 years of serving the sailing community. SEE US EXCLUSIVELY ON ***http://www.northland-yachts.com/*** Featured Listings Lake Minnetonka’s 37' Tartan $275,000 40' C&C $74,995 Premier Sailboat Marina 30' Baba $72,500 38' Morgan 382 $59,900 Now Reserving Slips for 34' Pacific Seacraft $139,000 40' Pacific Seacraft $295,000 the 2008 Sailing Season! email: [email protected] See our brokerage listings in the Call About Our Multi-List section of Northern Breezes. New Customer Northland Yachts Specials Port Superior Marina 34475 Port Superior Road 952-474-0600 Bayfield, Wisconsin 54814 Phone & Fax: (715) 779-3339 Mobile: (715) 209-5742 [email protected] S A I L I N G S C H O O L Safe, fun, learning Safe, fun, learning . Caribbean School of British Virgin Islands Learning Adventures in the best cruising grounds in the Caribbean. the Year ASA One-Week Courses in the Caribbean: Basic Cruising/Bareboat Charter, Cruising Multihull, Gold Standard Advanced Coastal Cruising, Fun only/Flotilla (No Experience). Feb 20-27, Feb 27-Mar 5 Basic Cruising/Bareboat Charter • Cruising Multihull • Flotilla • Sail & Dive/Flotilla Week aboard our boats or your own bareboat. -

Monthly Newsletter October 2000

October 2000 Monthly Newsletter From the Commodore Board of Directors Commodore Rob Wilson Im. Past Commodore Voldi Maki As I told you in a previous Telltale, dock, moving an existing dock to Vice Commodore Phil Spletter we are taking advantage of the low this location, or moving a small Secretary Gail Bernstein lake level to prepare for some pos- dock if we reduce the length of one Treasurer Becky Heston sible harbor modifications. Using or more of our existing docks. the recently completed topographic Race Commander Bob Harden Project 3 - Widen the north Buildings & Grounds Michael Stan survey, Ray Schull and Tom Groll have prepared some prelimi- ramp. This proposal is to ex- Fleet Commander Doug Laws cavate the area to allow us to Sail Training Brigitte Rochard nary plans for three possible modifications to the harbor. double the width of the current ramp. This would allow for AYC Staff Project 1 - Excavate the area multiple boats to launch/ General Manager Nancy Boulmay under the regular location of Docks retrieve and greatly reduce the Office Manager Cynthia Eck 2 - 6. This project would allow the congestion and waiting required at Caretakers Tom Cunningham docks to remain in their regular lo- the ramp. This work will also re- Vic Farrow cation until the lake level reaches duce the silt buildup on the ramp 655’. Currently docks 4, 5, and 6 by properly sloping back the have been relocated to the point ground from the new ramp edge. Austin Yacht Club approximately 21% of the time We also propose to repair the ero- 5906 Beacon Drive since 1980. -

July 2008 PDF Version (7.00MB)

Volume XIX No. 6 July 2008 Sailing for a Cause Boat Smart: Coast Guard Channel Jib Trimming Tips Airis Inflatable Kayak Review New Feature: Cruising Recipe ADA Regatta on Lake Minnetonka Over 500 New and Used Boats Two Great Lakes THREE GREAT MARINA SERVICE CENTERS LAKE SUPERIOR 715-392-7131 barkers-island-marina.com 250 Marina Dr., Superior, WI LAKE MICHIGAN LAKE SUPERIOR 218-834-6076 920-682-5117 knife-river-marina.com manitowoc-marina.com 115 Marina Rd., Knife River, MN 425 Maritime Dr., Manitowoc, WI R EPAIR & REFINISHING Before After 26 years of yacht refinishing experience using AWLGRIP® coating systems. Complete fiberglass/composite repairs & Custom wood working, refinishing. Cosmetic gelcoat repairs, blister fiberglass & composite repairs prevention & repair. Structural hull, deck and core repairs. N AVIGATION &ELECTRICAL S TORAGE &HANDLING Authorized Service • Indoor Heated & Outdoor Storage Expert advice, installation and servicing of all electrical systems and • Marine Travelifts navigation electronics. • Brownell Hydraulic Boat Handling Lifts & Trailers. M ECHANICAL S ERVICES R IGGING &SAILING S YSTEMS Diesel Propulsion Experienced sailors and riggers ready Systems Sales, to assist you with improvements to your Service and Repair boat’s rigging, sails & sail handling systems for cruising or racing Anchor handling systems, Custom Bow & Stern deck hardware upgrades: Thruster Installations hatches, ports, winches. for Power & Sail Steering system upgrades Servicing and Outfitting Coastal and World Cruisers Since 1970 Seawear -

Centerboard Classes NAPY D-PN Wind HC

Centerboard Classes NAPY D-PN Wind HC For Handicap Range Code 0-1 2-3 4 5-9 14 (Int.) 14 85.3 86.9 85.4 84.2 84.1 29er 29 84.5 (85.8) 84.7 83.9 (78.9) 405 (Int.) 405 89.9 (89.2) 420 (Int. or Club) 420 97.6 103.4 100.0 95.0 90.8 470 (Int.) 470 86.3 91.4 88.4 85.0 82.1 49er (Int.) 49 68.2 69.6 505 (Int.) 505 79.8 82.1 80.9 79.6 78.0 A Scow A-SC 61.3 [63.2] 62.0 [56.0] Akroyd AKR 99.3 (97.7) 99.4 [102.8] Albacore (15') ALBA 90.3 94.5 92.5 88.7 85.8 Alpha ALPH 110.4 (105.5) 110.3 110.3 Alpha One ALPHO 89.5 90.3 90.0 [90.5] Alpha Pro ALPRO (97.3) (98.3) American 14.6 AM-146 96.1 96.5 American 16 AM-16 103.6 (110.2) 105.0 American 18 AM-18 [102.0] Apollo C/B (15'9") APOL 92.4 96.6 94.4 (90.0) (89.1) Aqua Finn AQFN 106.3 106.4 Arrow 15 ARO15 (96.7) (96.4) B14 B14 (81.0) (83.9) Bandit (Canadian) BNDT 98.2 (100.2) Bandit 15 BND15 97.9 100.7 98.8 96.7 [96.7] Bandit 17 BND17 (97.0) [101.6] (99.5) Banshee BNSH 93.7 95.9 94.5 92.5 [90.6] Barnegat 17 BG-17 100.3 100.9 Barnegat Bay Sneakbox B16F 110.6 110.5 [107.4] Barracuda BAR (102.0) (100.0) Beetle Cat (12'4", Cat Rig) BEE-C 120.6 (121.7) 119.5 118.8 Blue Jay BJ 108.6 110.1 109.5 107.2 (106.7) Bombardier 4.8 BOM4.8 94.9 [97.1] 96.1 Bonito BNTO 122.3 (128.5) (122.5) Boss w/spi BOS 74.5 75.1 Buccaneer 18' spi (SWN18) BCN 86.9 89.2 87.0 86.3 85.4 Butterfly BUT 108.3 110.1 109.4 106.9 106.7 Buzz BUZ 80.5 81.4 Byte BYTE 97.4 97.7 97.4 96.3 [95.3] Byte CII BYTE2 (91.4) [91.7] [91.6] [90.4] [89.6] C Scow C-SC 79.1 81.4 80.1 78.1 77.6 Canoe (Int.) I-CAN 79.1 [81.6] 79.4 (79.0) Canoe 4 Mtr 4-CAN 121.0 121.6 -

2018 Charity Boat Auction Inventory Thank You for Your Generous

Thank you for your generous support of the Chesapeake Bay Maritime Museum ! 2018 Charity Boat Auction Inventory INV # DESCRIPTION TYPE MACGREGOR 26. 1987. Iconic trailerable weekender w/ 9.9 hp Honda 4 stroke o/b motor and good tandem axle 5009 untitled storage trailer. Fantastic bay and inland cruiser for most anywhere you can haul and launch her. Sea Sail of Cortez anyone ? Untitled storage trailer included. MD 6620 CH. CURRENT DESIGNS FITNESS KAYAK. Freedom model. 18 ft. long and 21 3/4 beam. Only 33 lbs. ! Kevlar 5019 construction with rudder and adjustable seat. As new condition . No paddle. Untitled, unregistered smallcraft not Paddle intended for motorization. AMF SUNFISH. 1969 Original owner boat used exclusively on fresh water lake in PA. Green stripe and splash 5031 guard. Well cared for and complete boat ready for more fun. Everyone loves a Sunfish. Why not treat yourself or Sail your kids to one. Untitled, unregistered smallcraft not intended for motorization. MISTRAL WINDSURFER. Really nice condition! Mast, boom, two sails (one brand new!), and sailbag included. 5038 Sail Untitled, unregistered smallcraft. BOMBARDIER SEADOO CHALLENGER 1800. 1997 twin Rotax water jet sport boat with bimini top. Motors need 5045 attention / replacement, jet pumps appear sound. Good project / parts boat, or buy it for the very nice galvanized, Power titled Sea Doo trailer. MD 3421 BJ. CAPE COD SENIOR KNOCKABOUT. Beautiful 23 ft. Spaulding Dunbar design built by Cape Cod Shipbuilding 1940's. Graceful c/b sloop with large cockpit and simple rig. Quite similiar to a Sakonnet 23 with a counter stern, W Class 22, Hodgon 21, etc..