Elevated Police Turnover Following the Summer of George Floyd Protests: a Synthetic Control Study∗

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Derek Chauvin Trial: 3 Questions America Needs to Ask About Seeking Racial Justice in a Court of Law

4/13/2021 Derek Chauvin trial: 3 questions America needs to ask about seeking racial justice in a court of law Close Academic rigor, journalistic flair A demonstration outside the Hennepin County Government Center in Minneapolis on March 29, 2021, the day Derek Chauvin’s trial began on charges he murdered George Floyd. Stephen Maturen/Getty Images Derek Chauvin trial: 3 questions America needs to ask about seeking racial justice in a court of law April 12, 2021 8.27am EDT There is a difference between enforcing the law and being the law. The world is now Author witnessing another in a long history of struggles for racial justice in which this distinction may be ignored. Derek Chauvin, a 45-year-old white former Minneapolis police officer, is on trial for Lewis R. Gordon third-degree murder and second-degree manslaughter for the May 25, 2020, death of Professor of Philosophy, University of George Floyd, a 46-year-old African American man. Connecticut There are three questions I find important to consider as the trial unfolds. These questions address the legal, moral and political legitimacy of any verdict in the trial. I offer them from my perspective as an Afro-Jewish philosopher and political thinker who studies oppression, justice and freedom. They also speak to the divergence between how a trial is conducted, what rules govern it – and the larger issue of racial justice raised by George Floyd’s death after Derek Chauvin pressed his knee on Floyd’s neck for more than nine minutes. They are questions that need to be asked: https://theconversation.com/derek-chauvin-trial-3-questions-america-needs-to-ask-about-seeking-racial-justice-in-a-court-of-law-158505 1/6 4/13/2021 Derek Chauvin trial: 3 questions America needs to ask about seeking racial justice in a court of law 1. -

Ferguson Effect Pre-Print

See discussions, stats, and author profiles for this publication at: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/292982609 Ferguson Effect pre-print Dataset · February 2016 READS 95 1 author: David C. Pyrooz University of Colorado Boulder 47 PUBLICATIONS 532 CITATIONS SEE PROFILE All in-text references underlined in blue are linked to publications on ResearchGate, Available from: David C. Pyrooz letting you access and read them immediately. Retrieved on: 12 April 2016 WAS THERE A FERGUSON EFFECT ON CRIME RATES IN LARGE U.S. CITIES? David C. Pyrooz* Department of Sociology University of Colorado Boulder Scott H. Decker School of Criminology and Criminal Justice Arizona State University Scott E. Wolfe Department of Criminology and Criminal Justice University of South Carolina John A. Shjarback School of Criminology and Criminal Justice Arizona State University * forthcoming in the Journal of Criminal Justice doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.jcrimjus.2016.01.001 This is the authors’ pre-print copy of the article. Please download and cite the post-print copy published on the JCJ website (link above) *Correspondence concerning this article should be addressed to David C. Pyrooz, Department of Sociology and Institute of Behavioral Science, UCB 483, University of Colorado Boulder, Boulder, CO, 80309-0483, USA. [email protected] 1 WAS THERE A FERGUSON EFFECT ON CRIME RATES IN LARGE U.S. CITIES?1 ABSTRACT Purpose: There has been widespread speculation that the events surrounding the shooting death of an unarmed young black man by a white police officer in Ferguson, Missouri—and a string of similar incidents across the country—have led to increases in crime in the United States. -

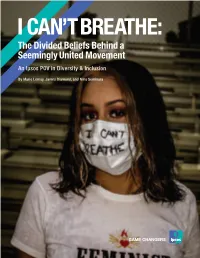

The Divided Beliefs Behind a Seemingly United Movement an Ipsos POV in Diversity & Inclusion

I CAN’T BREATHE: The Divided Beliefs Behind a Seemingly United Movement An Ipsos POV in Diversity & Inclusion By Marie Lemay, James Diamond, and Nina Seminara May 25 marks the one-year anniversary of the killing of George Floyd, an event that sparked outrage against police brutality—particularly toward Black people—in Floyd’s hometown of Minneapolis. Soon after, Americans in over 2,000 cities across all 50 states began organizing demonstrations, with protests extending beyond America’s borders to all corners of the world. Though most of the protests were peaceful, there were instances of violence, vandalism, destruction and death in several cities, provoking escalated police intervention, curfews and in some cases, the mobilization of the National Guard. The nationwide engagement with the Black Lives Matter movement throughout the 2020 protests, and data from a survey conducted nearly a year later showing 71% of Americans believed Chauvin is guilty of murder, paint the picture of a seem- ingly united people. ENGAGEMENT WITH THE GEORGE FLOYD PROTESTS MADE IT CLEAR THAT MANY AMERICANS ACROSS THE NATION ARE NO LONGER WILLING TO TOLERATE RACIAL INJUSTICE. Key Takeaways: • However, major gaps in perception exist when comparing how Black and White Americans understood and perceived the 2020 protests. • Ipsos conducted several national surveys throughout the duration of the Black Lives Matter protests to gain a sense of Americans’ attitudes and opinions towards the events that unfolded. Here’s what we found. 2 IPSOS | I CAN’T BREATHE: THE DIVIDED BELIEFS BEHIND A SEEMINGLY UNITED MOVEMENT What is your personal view on the Do you support or oppose the protests circumstances around the death and demonstrations taking place of George Floyd in Minneapolis? across the country following the death of George Floyd in Minneapolis? % It was murder. -

Transcript Was Exported on Jun 15., 2020 View Latest Versiun Here

27-CR-20-12951 Filed in District Court State of Minnesota - 7/7/2020 11:00 AM This transcript was exported on Jun 15., 2020 View latest versiun here.- Speaker 1: [silence] Speaker 1: Before they drive off, he’s parked right here, Its a fake bill from the Gentlemen, sorry. ' Kueng: - The driver in there? - LanerThe blue Benz? . I Speaker 1: Which one? Speaker3 : That blue one over there. Kueng Which one? Lane: yup-yup Just head back In. They're moving around a lot. Let me see your hands. George Floyd: Hey, man. I'm sorry! Lane: Stay in the car, let me see your other hand. George Floyd: l'm sorry, I'm sorry! Lane: Let me see your other hand! George Floyd: Please, Mr. Officer. Lane: Both hands. George Floyd: ldidn‘t do nothing. Lane: Put your fucking hands up right now! Let me see yOur other hand. Shawanda Hill: let him see your other hand George Floyd: All right. What l do though? What we do Mr Ofcer? Lane: Put your hand up there. Put your fucking hand up there! Jesus Christ, keep your fucking hands on the wheel. George Floyd: igot shot. [crosstalk 00:02:00]. EXHIB'T Lane: § 0‘3}?st Axon_Body_3_Video_2020-05-25_2008 (Completed 06/10/20) Transcript by Rev.com Page l of 25 27-CR-20-12951 Filed in District Court State of Minnesota 7/7/2020 11:00 AM This Lmnscript was exported on Jun IS. 3020 - view latest version here. Keep your fucking hands on the wheel. George Floyd: Yes, sir. -

Teen's Extradition Delayed

WISCONSIN CASES — DAILY KENOSHA COUNTY CASES — DAILY COVID-19 UPDATE POSITIVE +843 NEGATIVE +8,313 2,929 POSITIVE (+9) 32,185 NEGATIVE (+370) 62 DEATHS (+0) DAILY POSITIVE RATE 9.2% SOURCE: Wisconsin Department of Health Services website DEATHS +2 CURRENTLY HOSPITALIZED 309 dhs.wisconsin.gov/covid-19/county.htm For the safety of our staff and carrier force, delivery deadlines have been extended until 9 a.m. today MOSTLY SUNNY AND NOT AS WARM 78 • 57 FORECAST, A8 | SATURDAY, AUGUST 29, 2020 | kenoshanews.com | $2.00 COMPLETE COVERAGE | OFFICER-INVOLVED SHOOTING IN KENOSHA TEEN’S EXTRADITION DELAYED Held on $2M bond, he There is a $2 million bond at- Friday’s hearing at her request. Be- Rosenbaum, 36, of Kenosha. He Sunday. tached to the warrant seeking his cause of the COVID-19 pandemic, is also charged with two counts As Rittenhouse has been em- seeks private attorney return to Wisconsin. He is being the hearing was held remotely, and of first-degree recklessly endan- braced by right wing commenta- held in a juvenile detention facility only a portion of the hearing was gering safety for shooting his AR- tors and gun rights advocates. DENEEN SMITH in Illinois. visible to the public online. 15-style rifle toward other people High-profile conservative at- [email protected] At an extradition status hearing Rittenhouse is charged with who were not injured, and with torneys L. Lin Wood and John Kyle Rittenhouse won’t be re- in Lake County Friday, a public first degree intentional homicide possession of a dangerous weapon Pierce and the law firm Pierce turning to Kenosha County any- defender representing Ritten- for the death of 26-year-old Silver by a person under 18. -

30 Rock: Complexity, Metareferentiality and the Contemporary Quality Sitcom

30 Rock: Complexity, Metareferentiality and the Contemporary Quality Sitcom Katrin Horn When the sitcom 30 Rock first aired in 2006 on NBC, the odds were against a renewal for a second season. Not only was it pitched against another new show with the same “behind the scenes”-idea, namely the drama series Studio 60 on the Sunset Strip. 30 Rock’s often absurd storylines, obscure references, quick- witted dialogues, and fast-paced punch lines furthermore did not make for easy consumption, and thus the show failed to attract a sizeable amount of viewers. While Studio 60 on the Sunset Strip did not become an instant success either, it still did comparatively well in the Nielson ratings and had the additional advantage of being a drama series produced by a household name, Aaron Sorkin1 of The West Wing (NBC, 1999-2006) fame, at a time when high-quality prime-time drama shows were dominating fan and critical debates about TV. Still, in a rather surprising programming decision NBC cancelled the drama series, renewed the comedy instead and later incorporated 30 Rock into its Thursday night line-up2 called “Comedy Night Done Right.”3 Here the show has been aired between other single-camera-comedy shows which, like 30 Rock, 1 | Aaron Sorkin has aEntwurf short cameo in “Plan B” (S5E18), in which he meets Liz Lemon as they both apply for the same writing job: Liz: Do I know you? Aaron: You know my work. Walk with me. I’m Aaron Sorkin. The West Wing, A Few Good Men, The Social Network. -

Ads Play on Fear As Trump Raises Tension in Cities

C M Y K Nxxx,2020-07-22,A,001,Bs-4C,E1 Late Edition Today, clouds and sunshine, show- ers, thunderstorms, humid, high 90. Tonight, thunderstorms, low 77. To- morrow, strong thunderstorms, hu- mid, high 90. Weather map, Page C8. VOL. CLXIX . ...No. 58,762 © 2020 The New York Times Company NEW YORK, WEDNESDAY, JULY 22, 2020 $3.00 ADS PLAY ON FEAR AS TRUMP RAISES TENSION IN CITIES AN EFFORT TO TAR BIDEN Clashes With Protesters Used to Fuel Message of ‘Law and Order’ This article is by Maggie Ha- berman, Nick Corasaniti and Annie Karni. As President Trump deploys federal agents to Portland, Ore., and threatens to dispatch more to other cities, his re-election cam- paign is spending millions of dol- lars on several ominous television ads that promote fear and dovetail with his political message of “law and order.” The influx of agents in Portland has led to scenes of confrontations and chaos that Mr. Trump and his White House aides have pointed to as they try to burnish a false narrative about Democratic elected officials allowing danger- ous protesters to create wide- spread bedlam. The Trump campaign is driving home that message with a new ad that tries to tie its dark portrayal of Democratic-led cities to Mr. Trump’s main rival, Joseph R. Bi- den Jr. — with exaggerated im- ages intended to persuade view- PHOTOGRAPHS BY MASON TRINCA FOR THE NEW YORK TIMES ers that lawless anarchy would In Portland, Ore., federal officers in camouflage have used aggressive tactics like firing tear gas canisters against protesters, which included a peaceful line of mothers. -

Police Defunding and Reform : What Changes Are Needed? / by Olivia Ghafoerkhan

® About the Authors Olivia Ghafoerkhan is a nonfiction writer who lives in northern Virginia. She is the author of several nonfiction books for teens and young readers. She also teaches college composition. Hal Marcovitz is a former newspaper reporter and columnist who has written more than two hundred books for young readers. He makes his home in Chalfont, Pennsylvania. © 2021 ReferencePoint Press, Inc. Printed in the United States For more information, contact: ReferencePoint Press, Inc. PO Box 27779 San Diego, CA 92198 www.ReferencePointPress.com ALL RIGHTS RESERVED. No part of this work covered by the copyright hereon may be reproduced or used in any form or by any means—graphic, electronic, or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, taping, web distribution, or information storage retrieval systems—without the written permission of the publisher. Picture Credits: Cover: ChameleonsEye/Shutterstock.com 28: katz/Shutterstock.com 6: Justin Berken/Shutterstock.com 33: Vic Hinterlang/Shutterstock.com 10: Leonard Zhukovsky/Shutterstock.com 37: Maury Aaseng 14: Associated Press 41: Associated Press 17: Imagespace/ZUMA Press/Newscom 47: Tippman98x/Shutterstock.com 23: Associated Press 51: Stan Godlewski/ZUMA Press/Newscom LIBRARY OF CONGRESS CATALOGING- IN- PUBLICATION DATA Names: Ghafoerkhan, Olivia, 1982- author. Title: Police defunding and reform : what changes are needed? / by Olivia Ghafoerkhan. Description: San Diego, CA : ReferencePoint Press, 2021. | Series: Being Black in America | Includes bibliographical references and index. Identifiers: LCCN 2020048103 (print) | LCCN 2020048104 (ebook) | ISBN 9781678200268 (library binding) | ISBN 9781678200275 (ebook) Subjects: LCSH: Police administration--United States--Juvenile literature. | Police brutality--United States--Juvenile literature. | Discrimination in law enforcement--United States--Juvenile literature. -

News Release George Floyd Justice in Policing

Fortified by the Past… Focused on the Future RELEASE FOR: WEDNESDAY, FEBRUARY 24, 2021 CONTACT: Tkeban X.T. Jahannes (404) 944-1615 | [email protected] Civil Rights Leaders Call on Congress To Pass George Floyd Justice In Policing Act Today, civil rights leaders called on the U.S. House of Representatives to pass the George Floyd Justice in Policing Act – a critical step to holding law enforcement accountable for unconstitutional and unethical conduct. The 2020 killing of George Floyd sparked a year of national protests in all 50 states calling for an end to police brutality against Black and Brown communities and a demand for accountability in every sector of law enforcement. Addressing this nation’s history of violent, discriminatory policing requires passing legislation that advances systemic reforms rooted in transparency and accountability. It is the responsibility of the federal government to set standards on justice, policing, and safety. A vital step in this process is the passage of the George Floyd Justice in Policing Act, which recognizes the importance of stripping law enforcement of qualified immunity; creating a national registry of police misconduct complaints; declaring prohibitions for law enforcement profiling; limiting the transfer of military-grade equipment to state and local law enforcement; and restricting funds from law enforcement agencies that do not prohibit the use of chokeholds. “The killing of George Floyd held a mirror up to a truth about the American legal system. It showed us in the most stark and irrefutable way, that there are deep, fundamental problems with how this country allows law enforcement to intimidate, abuse, torture, and kill unarmed Black people. -

Blacklivesmatter—Getting from Contemporary Social Movements to Structural Change

Georgetown University Law Center Scholarship @ GEORGETOWN LAW 2021 #BlackLivesMatter—Getting from Contemporary Social Movements to Structural Change Jamillah Bowman Williams Georgetown University Law Center, [email protected] Naomi Mezey Georgetown University Law Center, [email protected] Lisa O. Singh Georgetown University, [email protected] This paper can be downloaded free of charge from: https://scholarship.law.georgetown.edu/facpub/2387 https://ssrn.com/abstract=3860435 California Law Review Online, Vol. 12, Reckoning and Reformation symposium. This open-access article is brought to you by the Georgetown Law Library. Posted with permission of the author. Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarship.law.georgetown.edu/facpub Part of the Criminal Law Commons, Law and Race Commons, and the Law and Society Commons #BlackLivesMatter— Getting from Contemporary Social Movements to Structural Change Jamillah Bowman Williams*, Naomi Mezey**, and Lisa Singh*** Introduction ................................................................................................. 2 I. Methodology ............................................................................................ 5 II. BLM: From Contemporary Social Movement to Structural Change ..... 6 A. Black Lives Matter as a Social Media Powerhouse ................. 6 B. Tweets and Streets: The Dynamic Relationship between Online and Offline Activism ................................................. 12 C. A Theory of How to Move from Social Media -

Chauvin Guilty Verdict: 'If Facebook Can Be Safer for Black People, Why Isn't That the Default Setting?' 21 April 2021, by Jessica Guynn, Usa Today

Chauvin guilty verdict: 'If Facebook can be safer for Black people, why isn't that the default setting?' 21 April 2021, by Jessica Guynn, Usa Today death last May under Chauvin's knee went viral and set off months of protests in the U.S. and abroad condemning police brutality and calling for racial justice. In anticipation of a verdict in the trial, Facebook pledged to remove posts from Facebook and Instagram that urged people to take up arms and any content that praised, celebrated or mocked George Floyd's death. It also designated Minneapolis as a "high risk location." "As we have done in emergency situations in the past, we may also limit the spread of content that our systems predict is likely to violate our Credit: Unsplash/CC0 Public Domain Community Standards in the areas of hate speech, graphic violence, and violence and incitement," Monika Bickert, vice president of content policy, said in a blog post. Facebook said it would take emergency steps to limit hate speech and calls for violence that "could Facebook took similar steps to curb flow of lead to civil unrest or violence" when the verdict misinformation and calls to violence in the came down in the murder trial of former aftermath of the 2020 presidential election. Minneapolis police officer Derek Chauvin. Emerson Brooking, resident fellow at the Atlantic The social media giant has used these powerful Council's Digital Forensic Research Lab, says moderation tools before. And that has Facebook Facebook's handling of the Chauvin verdict is a critics asking: Why don't they deploy them all the case study "in just how far we've come in the past time? year." "If Facebook can be safer for Black people, why "In 2020, the social media platforms struggled and isn't that the default setting?" said Rashad often failed to contain violent rhetoric, especially Robinson, president of Color Of Change. -

Iges Ish2 :I Dr Ndici

.........■■ -I- Bed a)mdbreakfcfasts: Intirmate acazommodaations, spt)ecialfood d - c i = = = = = = = ifofrrry Brpwn ot I win t-al ^ © w f eb © y s 8 soleId his hide-a-jjed-- ^ i c t 1 - in-oonly-1-<Jay-with------ 5 classified adi i ■ ^ o o l - B f ^ Shoot out^Sagee - B4 all 733-0626 Nolowl^ " - • HC f t n x i 2 5 ^ ' dnesday, July 2 2 , 1 9 8 7 82nd year, No. 203 Twin Fallslls, I d a h o W ednt J u d i g e s I q u a :i s h 2: i d ri i g i in d ic it m e rn t s do n o th in g o r d o so m eething." tl down afteiiler more thnn six m onthsI of appoint a jury comn:imrssiorier in the deci.sionion 1to throw out the Indict Shc said it wouldI 1be too costly invcstigatiia tio n in T%vin F o ils b y lawnw TVin'Falls County. m ents 10 mmir in u te s a fte r la w y e r s con- Jury seielection flc\awed nnd time-consuming ttto take the 21 cnforccnicment agencics. That jury commissiisioner, Kath* eluded theirieir arguments. dofendants through stistandard court DefenseISC attorneys for tho 21 de*lc* loen Noh of Kimberly,ly, is’ to com- In hin finnHnul argum ent. Wood, suid st for jury se- the county's,ty's jury selection proce- By CRAIG UNCOLNLN ■- in g o f ua mi aster list to the Belectionion proceedings, und she wiilw opt to use fendants.s filedf motions to quash the.he plete a now master list TimcS'Ncwa writer o f juiror ro i candidates, were in tho grand jury systemn ia g a in .