Strength of Faults on Mars from MOLA Topography

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Interpretations of Gravity Anomalies at Olympus Mons, Mars: Intrusions, Impact Basins, and Troughs

Lunar and Planetary Science XXXIII (2002) 2024.pdf INTERPRETATIONS OF GRAVITY ANOMALIES AT OLYMPUS MONS, MARS: INTRUSIONS, IMPACT BASINS, AND TROUGHS. P. J. McGovern, Lunar and Planetary Institute, Houston TX 77058-1113, USA, ([email protected]). Summary. New high-resolution gravity and topography We model the response of the lithosphere to topographic loads data from the Mars Global Surveyor (MGS) mission allow a re- via a thin spherical-shell flexure formulation [9, 12], obtain- ¡g examination of compensation and subsurface structure models ing a model Bouguer gravity anomaly ( bÑ ). The resid- ¡g ¡g ¡g bÓ bÑ in the vicinity of Olympus Mons. ual Bouguer anomaly bÖ (equal to - ) can be Introduction. Olympus Mons is a shield volcano of enor- mapped to topographic relief on a subsurface density interface, using a downward-continuation filter [11]. To account for the mous height (> 20 km) and lateral extent (600-800 km), lo- cated northwest of the Tharsis rise. A scarp with height up presence of a buried basin, we expand the topography of a hole Ö h h ¼ ¼ to 10 km defines the base of the edifice. Lobes of material with radius and depth into spherical harmonics iÐÑ up h with blocky to lineated morphology surround the edifice [1-2]. to degree and order 60. We treat iÐÑ as the initial surface re- Such deposits, known as the Olympus Mons aureole deposits lief, which is compensated by initial relief on the crust mantle =´ µh c Ñ c (hereinafter abbreviated as OMAD), are of greatest extent to boundary of magnitude iÐÑ . These interfaces the north and west of the edifice. -

No. 40. the System of Lunar Craters, Quadrant Ii Alice P

NO. 40. THE SYSTEM OF LUNAR CRATERS, QUADRANT II by D. W. G. ARTHUR, ALICE P. AGNIERAY, RUTH A. HORVATH ,tl l C.A. WOOD AND C. R. CHAPMAN \_9 (_ /_) March 14, 1964 ABSTRACT The designation, diameter, position, central-peak information, and state of completeness arc listed for each discernible crater in the second lunar quadrant with a diameter exceeding 3.5 km. The catalog contains more than 2,000 items and is illustrated by a map in 11 sections. his Communication is the second part of The However, since we also have suppressed many Greek System of Lunar Craters, which is a catalog in letters used by these authorities, there was need for four parts of all craters recognizable with reasonable some care in the incorporation of new letters to certainty on photographs and having diameters avoid confusion. Accordingly, the Greek letters greater than 3.5 kilometers. Thus it is a continua- added by us are always different from those that tion of Comm. LPL No. 30 of September 1963. The have been suppressed. Observers who wish may use format is the same except for some minor changes the omitted symbols of Blagg and Miiller without to improve clarity and legibility. The information in fear of ambiguity. the text of Comm. LPL No. 30 therefore applies to The photographic coverage of the second quad- this Communication also. rant is by no means uniform in quality, and certain Some of the minor changes mentioned above phases are not well represented. Thus for small cra- have been introduced because of the particular ters in certain longitudes there are no good determi- nature of the second lunar quadrant, most of which nations of the diameters, and our values are little is covered by the dark areas Mare Imbrium and better than rough estimates. -

Appendix a Conceptual Geologic Model

Newberry Geothermal Energy Establishment of the Frontier Observatory for Research in Geothermal Energy (FORGE) at Newberry Volcano, Oregon Appendix A Conceptual Geologic Model April 27, 2016 Contents A.1 Summary ........................................................................................................................................... A.1 A.2 Geological and Geophysical Context of the Western Flank of Newberry Volcano ......................... A.2 A.2.1 Data Sources ...................................................................................................................... A.2 A.2.2 Geography .......................................................................................................................... A.3 A.2.3 Regional Setting ................................................................................................................. A.4 A.2.4 Regional Stress Orientation .............................................................................................. A.10 A.2.5 Faulting Expressions ........................................................................................................ A.11 A.2.6 Geomorphology ............................................................................................................... A.12 A.2.7 Regional Hydrology ......................................................................................................... A.20 A.2.8 Natural Seismicity ........................................................................................................... -

Martian Crater Morphology

ANALYSIS OF THE DEPTH-DIAMETER RELATIONSHIP OF MARTIAN CRATERS A Capstone Experience Thesis Presented by Jared Howenstine Completion Date: May 2006 Approved By: Professor M. Darby Dyar, Astronomy Professor Christopher Condit, Geology Professor Judith Young, Astronomy Abstract Title: Analysis of the Depth-Diameter Relationship of Martian Craters Author: Jared Howenstine, Astronomy Approved By: Judith Young, Astronomy Approved By: M. Darby Dyar, Astronomy Approved By: Christopher Condit, Geology CE Type: Departmental Honors Project Using a gridded version of maritan topography with the computer program Gridview, this project studied the depth-diameter relationship of martian impact craters. The work encompasses 361 profiles of impacts with diameters larger than 15 kilometers and is a continuation of work that was started at the Lunar and Planetary Institute in Houston, Texas under the guidance of Dr. Walter S. Keifer. Using the most ‘pristine,’ or deepest craters in the data a depth-diameter relationship was determined: d = 0.610D 0.327 , where d is the depth of the crater and D is the diameter of the crater, both in kilometers. This relationship can then be used to estimate the theoretical depth of any impact radius, and therefore can be used to estimate the pristine shape of the crater. With a depth-diameter ratio for a particular crater, the measured depth can then be compared to this theoretical value and an estimate of the amount of material within the crater, or fill, can then be calculated. The data includes 140 named impact craters, 3 basins, and 218 other impacts. The named data encompasses all named impact structures of greater than 100 kilometers in diameter. -

![Arxiv:2003.06799V2 [Astro-Ph.EP] 6 Feb 2021](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/4215/arxiv-2003-06799v2-astro-ph-ep-6-feb-2021-614215.webp)

Arxiv:2003.06799V2 [Astro-Ph.EP] 6 Feb 2021

Thomas Ruedas1,2 Doris Breuer2 Electrical and seismological structure of the martian mantle and the detectability of impact-generated anomalies final version 18 September 2020 published: Icarus 358, 114176 (2021) 1Museum für Naturkunde Berlin, Germany 2Institute of Planetary Research, German Aerospace Center (DLR), Berlin, Germany arXiv:2003.06799v2 [astro-ph.EP] 6 Feb 2021 The version of record is available at http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.icarus.2020.114176. This author pre-print version is shared under the Creative Commons Attribution Non-Commercial No Derivatives License (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0). Electrical and seismological structure of the martian mantle and the detectability of impact-generated anomalies Thomas Ruedas∗ Museum für Naturkunde Berlin, Germany Institute of Planetary Research, German Aerospace Center (DLR), Berlin, Germany Doris Breuer Institute of Planetary Research, German Aerospace Center (DLR), Berlin, Germany Highlights • Geophysical subsurface impact signatures are detectable under favorable conditions. • A combination of several methods will be necessary for basin identification. • Electromagnetic methods are most promising for investigating water concentrations. • Signatures hold information about impact melt dynamics. Mars, interior; Impact processes Abstract We derive synthetic electrical conductivity, seismic velocity, and density distributions from the results of martian mantle convection models affected by basin-forming meteorite impacts. The electrical conductivity features an intermediate minimum in the strongly depleted topmost mantle, sandwiched between higher conductivities in the lower crust and a smooth increase toward almost constant high values at depths greater than 400 km. The bulk sound speed increases mostly smoothly throughout the mantle, with only one marked change at the appearance of β-olivine near 1100 km depth. -

Shape of the Northern Hemisphere of Mars from the Mars Orbiter Laser Altimeter (MOLA)

GEOPHYSICAL RESEARCH LETTERS, VOL. 25, NO. 24, PAGES 4393-4396, DECEMBER 15, 1998 Shape of the northern hemisphere of Mars from the Mars Orbiter Laser Altimeter (MOLA) Maria T. Zuber1,2, David E. Smith2, Roger J. Phillips3, Sean C. Solomon4, W. Bruce Banerdt5,GregoryA.Neumann1,2, Oded Aharonson1 Abstract. Eighteen profiles of ∼N-S-trending topography potentially change the flattening by at most 5%. Allowing from the Mars Orbiter Laser Altimeter (MOLA) are used for the 3.1-km offset of the center of mass (COM) from the to analyze the shape of Mars’ northern hemisphere. MOLA center of figure (COF) along the polar axis [Smith and Zuber, observations show smaller northern hemisphere flattening 1996], we can expect the flattening of the full planet to be than previously thought. The hypsometric distribution is less than that of the northern hemisphere by ∼ 15%, or narrowly peaked with > 20% of the surface lying within 200 1/174 6. This is significantly less than the earlier value m of the mean elevation. Low elevation correlates with low of 1/154.4[Bills and Ferrari, 1978] and slightly less than surface roughness, but the elevation and roughness may re- the ellipsoidal value of 1/166.53 [Smith and Zuber, 1996] flect different mechanisms. Bouguer gravity indicates less that have been used in geophysical analyses. However, it variability in crustal thickness and/or lateral density struc- is larger than the flattening of 1/192 used in making maps ture than previously expected. The 3.1-km offset between [Wu, 1991]. Consideration of ice cap topography will further centers of mass and figure along the polar axis results in a decrease the value. -

Sinuous Ridges in Chukhung Crater, Tempe Terra, Mars: Implications for Fluvial, Glacial, and Glaciofluvial Activity

This is a repository copy of Sinuous ridges in Chukhung crater, Tempe Terra, Mars: Implications for fluvial, glacial, and glaciofluvial activity. White Rose Research Online URL for this paper: http://eprints.whiterose.ac.uk/166644/ Version: Published Version Article: Butcher, F.E.G. orcid.org/0000-0002-5392-7286, Balme, M.R., Conway, S.J. et al. (6 more authors) (2021) Sinuous ridges in Chukhung crater, Tempe Terra, Mars: Implications for fluvial, glacial, and glaciofluvial activity. Icarus, 357. 114131. ISSN 0019-1035 https://doi.org/10.1016/j.icarus.2020.114131 Reuse This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) licence. This licence allows you to distribute, remix, tweak, and build upon the work, even commercially, as long as you credit the authors for the original work. More information and the full terms of the licence here: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/ Takedown If you consider content in White Rose Research Online to be in breach of UK law, please notify us by emailing [email protected] including the URL of the record and the reason for the withdrawal request. [email protected] https://eprints.whiterose.ac.uk/ Journal Pre-proof Sinuous ridges in Chukhung crater, Tempe Terra, Mars: Implications for fluvial, glacial, and glaciofluvial activity Frances E.G. Butcher, Matthew R. Balme, Susan J. Conway, Colman Gallagher, Neil S. Arnold, Robert D. Storrar, Stephen R. Lewis, Axel Hagermann, Joel M. Davis PII: S0019-1035(20)30473-5 DOI: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.icarus.2020.114131 Reference: YICAR 114131 To appear in: Icarus Received date: 2 June 2020 Revised date: 19 August 2020 Accepted date: 28 September 2020 Please cite this article as: F.E.G. -

Pre-Mission Insights on the Interior of Mars Suzanne E

Pre-mission InSights on the Interior of Mars Suzanne E. Smrekar, Philippe Lognonné, Tilman Spohn, W. Bruce Banerdt, Doris Breuer, Ulrich Christensen, Véronique Dehant, Mélanie Drilleau, William Folkner, Nobuaki Fuji, et al. To cite this version: Suzanne E. Smrekar, Philippe Lognonné, Tilman Spohn, W. Bruce Banerdt, Doris Breuer, et al.. Pre-mission InSights on the Interior of Mars. Space Science Reviews, Springer Verlag, 2019, 215 (1), pp.1-72. 10.1007/s11214-018-0563-9. hal-01990798 HAL Id: hal-01990798 https://hal.archives-ouvertes.fr/hal-01990798 Submitted on 23 Jan 2019 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. Open Archive Toulouse Archive Ouverte (OATAO ) OATAO is an open access repository that collects the wor of some Toulouse researchers and ma es it freely available over the web where possible. This is an author's version published in: https://oatao.univ-toulouse.fr/21690 Official URL : https://doi.org/10.1007/s11214-018-0563-9 To cite this version : Smrekar, Suzanne E. and Lognonné, Philippe and Spohn, Tilman ,... [et al.]. Pre-mission InSights on the Interior of Mars. (2019) Space Science Reviews, 215 (1). -

Appendix I Lunar and Martian Nomenclature

APPENDIX I LUNAR AND MARTIAN NOMENCLATURE LUNAR AND MARTIAN NOMENCLATURE A large number of names of craters and other features on the Moon and Mars, were accepted by the IAU General Assemblies X (Moscow, 1958), XI (Berkeley, 1961), XII (Hamburg, 1964), XIV (Brighton, 1970), and XV (Sydney, 1973). The names were suggested by the appropriate IAU Commissions (16 and 17). In particular the Lunar names accepted at the XIVth and XVth General Assemblies were recommended by the 'Working Group on Lunar Nomenclature' under the Chairmanship of Dr D. H. Menzel. The Martian names were suggested by the 'Working Group on Martian Nomenclature' under the Chairmanship of Dr G. de Vaucouleurs. At the XVth General Assembly a new 'Working Group on Planetary System Nomenclature' was formed (Chairman: Dr P. M. Millman) comprising various Task Groups, one for each particular subject. For further references see: [AU Trans. X, 259-263, 1960; XIB, 236-238, 1962; Xlffi, 203-204, 1966; xnffi, 99-105, 1968; XIVB, 63, 129, 139, 1971; Space Sci. Rev. 12, 136-186, 1971. Because at the recent General Assemblies some small changes, or corrections, were made, the complete list of Lunar and Martian Topographic Features is published here. Table 1 Lunar Craters Abbe 58S,174E Balboa 19N,83W Abbot 6N,55E Baldet 54S, 151W Abel 34S,85E Balmer 20S,70E Abul Wafa 2N,ll7E Banachiewicz 5N,80E Adams 32S,69E Banting 26N,16E Aitken 17S,173E Barbier 248, 158E AI-Biruni 18N,93E Barnard 30S,86E Alden 24S, lllE Barringer 29S,151W Aldrin I.4N,22.1E Bartels 24N,90W Alekhin 68S,131W Becquerei -

DETAILED GEOMORPHOLOGIC-TECTONIC MAPPING of the TEMPE TERRA REGION, MARS UNDER CONSIDERATION of CHRONOSTRATIGRAPHIC ASPECTS A. Neesemann1, S

45th Lunar and Planetary Science Conference (2014) 2313.pdf DETAILED GEOMORPHOLOGIC-TECTONIC MAPPING OF THE TEMPE TERRA REGION, MARS UNDER CONSIDERATION OF CHRONOSTRATIGRAPHIC ASPECTS A. Neesemann1, S. van Gasselt1, S. Walter1, 1Inst. of Geological Sciences, Freie Universitaet Berlin, Planetary Sciences and Remote Sensing Group, Dep. of Earth Sciences, Malteserstr. 74-100, 12249 Berlin, (Germany); [email protected]; Introduction: We have completed a new fice of 3.51 Ga which is highly consistent with own age 1:3,000,000 geomorphologic-tectonic map of Tempe determinations of 3.53 Ga. However, our detailed in- Terra along with parts of sorrounding units based on vestigation of the volcano using CTX data reveals new -1 Context Camera [1] (CTX) image data at ˜6 mpx insights into relative and absolute stratigraphic relations resolution. CTX data gaps that only make out a few between volcanic emplacement and rifting. Narrow lava percent of the mapping area were filled with data flows (Fig.1a) which represent later eruptions and acquired by the High Resolution Stereo Camera [2, 3] should therefore be younger than 3.53 Ga (or 3.51 Ga) (HRSC) at resolutions between 12.5 to 25 mpx-1. While are cut by major curvlinear border faults of Tempe Fos- the focus of this map lies on the study of recent surface sae and linear, narrow faults of Mareotis Fossae. Thus, processes and the complex volcano-tectonic history rifting or at least faulting seems to have been active after that has sustainably shaped Tempe Terra, adjacent the latest eruptions. units associated with the formation of major geologic Ancient lakes and river beds: In the eastern part regions (Arcadia Planitia, Kasei Valles, Tharsis) were of Tempe Terra, Nochian cratered units are often carved also included to get a comprehensive insight in the by irregular, often labyrinth-like, flat-floored and rim- regional geology. -

Cambridge University Press 978-1-107-03629-1 — the Atlas of Mars Kenneth S

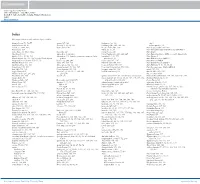

Cambridge University Press 978-1-107-03629-1 — The Atlas of Mars Kenneth S. Coles, Kenneth L. Tanaka, Philip R. Christensen Index More Information Index Note: page numbers in italic indicates figures or tables Acheron Fossae 76, 76–77 cuesta 167, 169 Hadriacus Cavi 183 orbit 1 Acidalia Mensa 86, 87 Curiosity 9, 32, 62, 195 Hadriacus Palus 183, 184–185 surface gravity 1, 13 aeolian, See wind; dunes Cyane Catena 82 Hecates Tholus 102, 103 Mars 3 spacecraft 6, 201–202 Aeolis Dorsa 197 Hellas 30, 30, 53 Mars Atmosphere and Volatile Evolution (MAVEN) 9 Aeolis Mons, See Mount Sharp Dao Vallis 227 Hellas Montes 225 Mars Chart 1 Alba Mons 80, 81 datum (zero elevation) 2 Hellas Planitia 220, 220, 226, 227 Mars Exploration Rovers (MER), See Spirit, Opportunity albedo 4, 5,6,10, 56, 139 deformation 220, See also contraction, extension, faults, hematite 61, 130, 173 Mars Express 9 alluvial deposits 62, 195, 197, See also fluvial deposits grabens spherules 61,61 Mars Global Surveyor (MGS) 9 Amazonian Period, history of 50–51, 59 Deimos 62, 246, 246 Henry crater 135, 135 Mars Odyssey (MO) 9 Amenthes Planum 143, 143 deltas 174, 175, 195 Herschel crater 188, 189 Mars Orbiter Mission (MOM) 9 Apollinaris Mons 195, 195 dikes, igneous 82, 105, 155 Hesperia Planum 188–189 Mars Pathfinder 9, 31, 36, 60,60 Aram Chaos 130, 131 domical mound 135, 182, 195 Hesperian Period, history of 50, 188 Mars Reconnaissance Orbiter (MRO) 9 Ares Vallis 129, 130 Dorsa Argentea 239, 240 Huygens crater 183, 185 massif 182, 224 Argyre Planitia 213 dunes 56, 57,69–70, 71, 168, 185, -

The Surface of Mars Michael H. Carr Index More Information

Cambridge University Press 978-0-521-87201-0 - The Surface of Mars Michael H. Carr Index More information Index Accretion 277 Areocentric longitude Sun 2, 3 Acheron Fossae 167 Ares Vallis 114, 116, 117, 231 Acid fogs 237 Argyre 5, 27, 159, 160, 181 Acidalia Planitia 116 floor elevation 158 part of low around Tharsis 85 floor Hesperian in age 158 Admittance 84 lake 156–8 African Rift Valleys 95 Arsia Mons 46–9, 188 Ages absolute 15, 23 summit caldera 46 Ages, relative, by remote sensing 14, 23 Dikes 47 Alases 176 magma supply rate 51 Alba Patera 2, 17, 48, 54–7, 92, 132, 136 Arsinoes Chaos 115, 117 low slopes 54 Ascreus Mons 46, 49, 51 flank fractures 54 summit caldera 49 fracture ring 54 flank vents 49 dikes 55 rounded terraces 50 pit craters 55, 56, 88 Asteroids 24 sheet flows 55, 56 Astronomical unit 1, 2 Tube-fed flows 55, 56 Athabasca Vallis 59, 65, 122, 125, 126 lava ridges 55 Atlantis Chaos 151 dilatational faults 55 Atmosphere collapse 262 channels 56, 57 Atmosphere, chemical composition 17 pyroclastic deposits 56 circulation 8 graben 56, 84, 86 convective boundary layer 9 profile 54 CO2 retention 260 Albedo 1, 9, 193 early Mars 263, 271 Albor Tholus 60 eddies 8 ALH84001 20, 21, 78, 267, 273–4, 277 isotopic composition 17 Alpha Particle X-ray Spectrometer 232 mass 16 Alpha Proton-ray Spectrometer 231 meridional flow 1 Alpheus Colles 160 pressure variations and range 5, 16 AlQahira 122 temperatures 6–8 Amazonian 277 scale height 5, 16 Amazonis Planitia 45, 64, 161, 195 water content 11 flows 66, 68 column water abundance 174 low