The Northern Ireland Women's Coalition: Origin, Influence And

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Peter Robinson DUP Reg Empey UUP Robin Newton DUP David Walter Ervine PUP Naomi Rachel Long Alliance Michael Stewart Copeland UUP

CANDIDATES ELECTED TO THE NORTHERN IRELAND ASSEMBLY 26 NOVEMBER 2003 Belfast East: Peter Robinson DUP Reg Empey UUP Robin Newton DUP David Walter Ervine PUP Naomi Rachel Long Alliance Michael Stewart Copeland UUP Belfast North: Nigel Alexander Dodds DUP Gerry Kelly Sinn Fein Nelson McCausland DUP Fred Cobain UUP Alban Maginness SDLP Kathy Stanton Sinn Fein Belfast South: Michael McGimpsey UUP Simon Mark Peter Robinson DUP John Esmond Birnie UUP Carmel Hanna SDLP Alex Maskey Sinn Fein Alasdair McDonnell SDLP Belfast West: Gerry Adams Sinn Fein Alex Atwood SDLP Bairbre de Brún Sinn Fein Fra McCann Sinn Fein Michael Ferguson Sinn Fein Diane Dodds DUP East Antrim: Roy Beggs UUP Sammy Wilson DUP Ken Robinson UUP Sean Neeson Alliance David William Hilditch DUP Thomas George Dawson DUP East Londonderry: Gregory Campbell DUP David McClarty UUP Francis Brolly Sinn Fein George Robinson DUP Norman Hillis UUP John Dallat SDLP Fermanagh and South Tyrone: Thomas Beatty (Tom) Elliott UUP Arlene Isobel Foster DUP* Tommy Gallagher SDLP Michelle Gildernew Sinn Fein Maurice Morrow DUP Hugh Thomas O’Reilly Sinn Fein * Elected as UUP candidate, became a member of the DUP with effect from 15 January 2004 Foyle: John Mark Durkan SDLP William Hay DUP Mitchel McLaughlin Sinn Fein Mary Bradley SDLP Pat Ramsey SDLP Mary Nelis Sinn Fein Lagan Valley: Jeffrey Mark Donaldson DUP* Edwin Cecil Poots DUP Billy Bell UUP Seamus Anthony Close Alliance Patricia Lewsley SDLP Norah Jeanette Beare DUP* * Elected as UUP candidate, became a member of the DUP with effect from -

OFFICIAL REPORT (Hansard)

OFFICIAL REPORT (Hansard) Vol u m e 2 (15 February 1999 to 15 July 1999) BELFAST: THE STATIONERY OFFICE LTD £70.00 © Copyright The New Northern Ireland Assembly. Produced and published in Northern Ireland on behalf of the Northern Ireland Assembly by the The Stationery Office Ltd, which is responsible for printing and publishing Northern Ireland Assembly publications. ISBN 0 339 80001 1 ASSEMBLY MEMBERS (A = Alliance Party; NIUP = Northern Ireland Unionist Party; NIWC = Northern Ireland Women’s Coalition; PUP = Progressive Unionist Party; SDLP = Social Democratic and Labour Party; SF = Sinn Fein; DUP = Ulster Democratic Unionist Party; UKUP = United Kingdom Unionist Party; UUP = Ulster Unionist Party; UUAP = United Unionist Assembly Party) Adams, Gerry (SF) (West Belfast) Kennedy, Danny (UUP) (Newry and Armagh) Adamson, Ian (UUP) (East Belfast) Leslie, James (UUP) (North Antrim) Agnew, Fraser (UUAP) (North Belfast) Lewsley, Patricia (SDLP) (Lagan Valley) Alderdice of Knock, The Lord (Initial Presiding Officer) Maginness, Alban (SDLP) (North Belfast) Armitage, Pauline (UUP) (East Londonderry) Mallon, Seamus (SDLP) (Newry and Armagh) Armstrong, Billy (UUP) (Mid Ulster) Maskey, Alex (SF) (West Belfast) Attwood, Alex (SDLP) (West Belfast) McCarthy, Kieran (A) (Strangford) Beggs, Roy (UUP) (East Antrim) McCartney, Robert (UKUP) (North Down) Bell, Billy (UUP) (Lagan Valley) McClarty, David (UUP) (East Londonderry) Bell, Eileen (A) (North Down) McCrea, Rev William (DUP) (Mid Ulster) Benson, Tom (UUP) (Strangford) McClelland, Donovan (SDLP) (South -

M Henderson MBE, WA Leathem, SP Porte

1 June, 2017 Chairman: Councillor T Morrow Vice-Chairman: Councillor A Givan Aldermen: M Henderson MBE, W A Leathem, S P Porter and J Tinsley Councillors: N Anderson, R T Beckett, J Gray MBE, V Kamble, H Legge, A McIntyre, S Skillen, N Trimble and R Walker Ex Officio The Right Worshipful the Mayor, Councillor R B Bloomfield MBE Deputy Mayor, Alderman S Martin The Monthly Meeting of the Leisure & Community Development Committee will be held in the Chestnut Room, Island Civic Centre, The Island, Lisburn, on Tuesday, 6 June, 2017, at 5.30 pm for the transaction of business on the undernoted agenda. Hot food will be available from 5.00 pm in Lighters Restaurant. You are requested to attend. Dr THERESA DONALDSON Chief Executive Lisburn & Castlereagh City Council 1 1. Apologies 2. Declarations of Interest 3. Minutes – Meeting of the Committee held on 2 May, 2017 (copy attached) 4. Report from the Director of Leisure & Community Services 4.1 Lands at Former Dunmurry High School Site, Seymour Hill 4.2 Linen Biennale 4.3 Departmental Budget Report 4.4 World War One Decade of Centenaries: Exhibitions & Projects 4.4.1 Lisburn 1918-23 Exhibition 4.4.2 Website Commemorating Lisburn and District WW1 Dead 4.4.3 Lisnagarvey Hockey Club and WW1 4.4.4 Proposed Blue Plaque for the Suffragette: Mrs Lilian Metge of Lisburn 4.4.5 Proposed New Plaque to Identify the ‘Peace Tree’ Planted in 1920 by Lisburn Board of Guardians 4.5 Display to Mark the 500th Anniversary of the Reformation 4.6 Google Cultural Institute Online Site 4.7 Report from Mr Ross Gillanders, -

Irish Language Andself- Determination the 'Rights'

27 MAY 1997 May/June 1997 Connolly Association: campaigning for a united and independent Ireland The 'rights' way Irish language Peter Berresfbrd forward for andself- Tory Sound Ellis: the sinking peace In Ireland determination Jiiishb&fin, of HMSWasp Page 7 Connolly Column: Page 6 Page 12 .jpsR ' . * • "i7?'.' | he dramatic landslide victory of as the potential pitfalls, are many. °EACE PROCESS respond to the new Labour govern- Moves on all of these key areas, Tony Blair and the Labour The electoral success of Sinn Fein ment in the coming months, will be along with a much hoped-for renewal Party has changed the political in West Belfast and Mid Ulster con- their response to Orange Order of the IRA ceasefire, and an end to all landscape of Britain and opened firmed beyond any doubt the party's marches in full, was indeed welcome. attempts to orchestrate a repeat of the forms of political and sectarian up a new opportunity for reviv- claim to have a mandate to speak on However, it is essential that the new the previous showdowns at violence, are essential for creating the ing the Irish peace process. behalf of a significant part of the commission is given powers immedi- Drumcree. It is essential that they do right conditions for progress. 1Labour's 179 seat majority in the nationalist population in die North. ately to ban and reroute contentious not allow some of the worst examples Labour has both an opportunity House of Commons ensures that the Their success increases both the marches where local agreements are of un mist triumphalism to win out and the ability to act decisively over British government is no longer at the need and desirability of their indu- not reached. -

8Th Congress Programme and Abstract Book British Association For

British Association for the Study and Prevention of Child Abuse and Neglect 8th Congress “Keeping Children Safe in an Uncertain World: Learning from Evidence and Practice” Programme and Abstract Book 15th – 18th April 2012 Queen’s University Belfast, Northern Ireland, UK BASPCAN was established to help to protect children from significant harm or risk of such harm, by providing support and information to professionals whose work involves them in the prevention, detection and treatment of child abuse and neglect. It is a unique multi-disciplinary organisation which brings together personnel from all agencies who work in the field of child protection. We have an interested, enthusiastic and knowledgeable membership which includes social workers, medical and nursing personnel, lawyers, police officers, psychologists, psychiatrists, therapists, teachers, researchers, academics and policy-makers. BASPCAN achieves this by: • Organising Study days, Seminars and Conferences throughout the UK • Holding a tri-ennial National Congress • Supporting the BASPCAN Regional Branch Network • Encouraging multi-disciplinary collaboration • Publishing a regular newsletter, ‘BASPCAN News’ • Providing responses to Government, Inquiries, Consultations, the media and others on issues relating to child maltreatment • Publishing, with Wiley Blackwell, the official journal of the Association, ‘Child Abuse Review’ • A Research Award Programme for BASPCAN members undertaking or completing small scale research projects on child protection BASPCAN works with a wide -

Report on Rights, Safeguards, Equality Issues and Victims

Session 2006/2007 Report on Rights, Safeguards, Equality Issues and Victims TOGETHER WITH THE MINUTES OF PROCEEDINGS, OFFICIAL REPORT AND PAPERS SUBMITTED BY PARTIES TO THE COMMITTEE ON THE PREPARATION FOR GOVERNMENT Directed by the Secretary of State for Northern Ireland to be printed 19 September 2006 £29.00 Committee on the Preparation for Government Under the terms of the Northern Ireland Act 2006 the Secretary of State for Northern Ireland, the Rt. Hon Peter Hain MP, directed on 26 May 2006 that a Committee should be established on the necessary business relating to the preparation for government. On 12 June 2006, the Secretary of State directed that the Committee should be chaired by the deputy presiding officers, Mr Jim Wells and Mr Francie Molloy. Membership The Committee has 14 members with a quorum of seven. The membership of the Committee since its establishment on 26 May 2006 is as follows: Mark Durkan MP Dr Sean Farren David Ford Michelle Gildernew MP Danny Kennedy Naomi Long Dr William McCrea MP Dr Alasdair McDonnell MP Alan McFarland Martin McGuinness MP *David McNarry Lord Morrow Conor Murphy MP Ian Paisley Jnr * Mr McNarry replaced Mr Michael McGimpsey on 10 July 2006. At its meeting on 12 June 2006, the Committee agreed that deputies could attend if members of the Committee were unable to do so. The following members attended at various times: Billy Armstrong George Ennis Alban Maginness Alex Attwood Michael Ferguson Alex Maskey Esmond Birnie Arlene Foster Sean Neeson Dominic Bradley William Hay Dermot Nesbitt PJ Bradley -

Client DEL Project Review of Widening Participation Funded

Client DEL Project Review of Widening Participation Funded Initiatives Appendices FINAL Division Public Sector Consultancy October 2010 Department for Employment and Learning Review of Widening Participation Funded Initiatives Final Appendices October 2010 Prepared On Behalf Of Department for Employment and Learning Review of Widening Participation Funded Initiatives Final Appendices October 2010 Table of Contents APPENDIX 1 – CONSULTEES ..............................................................................................................5 APPENDIX 2 – SUMMARY OF HEI ACCESS AGREEMENTS ............................................................7 APPENDIX 3 – RESEARCH INTO WIDENING PARTICIPATION ......................................................15 1.1 INTRODUCTION............................................................................................................................. 15 1.2 HE IN NI: A REPORT ON FACTORS ASSOCIATED WITH PARTICIPATION AND MIGRATION (2006) 15 1.3 STAYING THE COURSE: AN ECONOMETRIC ANALYSIS OF THE CHARACTERISTICS MOST ASSOCIATED WITH STUDENT ATTRITION BEYOND THE FIRST YEAR OF HE - MAIN REPORT (MARK BAILEY AND VANI K BOROOAH, UU; MAY 2006) .....................................................................................17 1.4 REVIEW OF WIDENING PARTICIPATION RESEARCH: ADDRESSING THE BARRIERS TO PARTICIPATION IN HIGHER EDUCATION - A REPORT TO HEFCE BY THE UNIVERSITY OF YORK, HEA AND INSTITUTE FOR ACCESS STUDIES (JULY 2006) ....................................................................19 -

Devolution Monitoring Programme 2006-08

DEVOLUTION MONITORING PROGRAMME 2006-08 Northern Ireland Devolution Monitoring Report January 2007 Professor Rick Wilford & Robin Wilson Queen’s University Belfast (eds.) ISSN 1751-3871 The Devolution Monitoring Programme From 1999 to 2005 the Constitution Unit at University College London managed a major research project monitoring devolution across the UK through a network of research teams. 103 reports were produced during this project, which was funded by the Economic and Social Research Council (grant number L 219 252 016) and the Leverhulme Nations and Regions Programme. Now, with further funding from the Economic and social research council and support from several government departments, the monitoring programme is continuing for a further three years from 2006 until the end of 2008. Three times per year, the research network produces detailed reports covering developments in devolution in five areas: Scotland, Wales, Northern Ireland, the Englsh Regions, and Devolution and the Centre. The overall monitoring project is managed by Professor Robert Hazell and Akash Paun at the Constitution Unit, UCL and the team leaders are as follows: Scotland: Peter Jones Honorary Senior Research Fellow, The Constitution Unit, UCL Former political correspondent for The Economist Wales: Dr Richard Wyn Jones & Dr Roger Scully Institute of Welsh Politics, University of Wales, Aberystwyth Northern Ireland: Professor Rick Wilford & Robin Wilson Queen’s University, Belfast English Regions: Martin Burch & James Rees, IPEG, University of Manchester Alan Harding, SURF, University of Salford The Centre: Professor Robert Hazell, The Constitution Unit, UCL Akash Paun, The Constitution Unit, UCL The Constitution Unit and the rest of the research network is grateful to all the funders of the devolution monitoring programme. -

Leverhulme-Funded Monitoring Programme

Leverhulme-funded monitoring programme Northern Ireland report 2 February 2000 Contents Summary Robin Wilson 3 Getting going Rick Wilford 4 The media Liz Fawcett 17 Public attitudes and identity (Nil return) Finance Paul Gorecki 19 Political parties and elections (Nil return) Intergovernmental relations Graham Walker/ 21 Robin Wilson Relations with the EU Elizabeth Meehan 26 Public policies Robin Wilson 30 Into suspension Robin Wilson 32 2 Summary The last monitoring report from Northern Ireland was unique in the tripartite study because only in Northern Ireland had powers not been transferred to the new devolved institutions. This, second, report is also unique in that, whatever crises the Scottish and Welsh executives have experienced, the Northern Ireland Executive Committee has, within the space of a little over two months, not only come but also, for the moment at least, gone. If ever the point needed proving that the region is, constitutionally and politically, sui generis, this latest episode on the roller coaster blandly described as the Northern Ireland ‘peace process’ surely underscored it. This report is therefore, in its tenor, once more a victim of the hypertrophy of politics in Northern Ireland. Relatively little emphasis is given to the ‘normal’ concerns addressed elsewhere, compared with the iterative reworking of the already well-worn themes in the political discourse—of decommissioning and devolution. As a result, what would come under the headings of the devolved government and the assembly/parliament in the other reports here focuses more on the establishment of the institutions than on their substantive work. And there is inevitably a long exegesis of the process leading to their demise. -

Assembly Portrait Key.Qxd

© Copyright of the Northern Ireland Assembly 2003. 1 4 2 3 7 103 5 6 8 80 83 84 85 24 63 82 101 102 23 44 45 46 47 52 53 55 62 64 65 10 25 26 61 81 104 50 54 9 12 22 49 51 86 14 48 108 58 87 88 89 90 11 13 28 27 56 66 67 91 106 29 68 69 107 109 110 15 30 57 70 105 17 16 31 93 59 72 92 94 32 34 71 18 33 95 114 115 60 73 111 37 96 20 36 97 112 19 35 38 43 74 75 113 41 100 76 78 79 98 99 116 40 77 42 39 117 21 1.Lord Alderdice (Speaker) 25. Mr Norman Boyd (NIUP) 48. Mr Patrick Roche (NIUP) 71. Ms Jane Morrice (NIWC) 94.Mr Mitchel McLaughlin (Sinn Féin) 2. Mr Arthur Moir (Clerk to the Assembly/Chief Executive) 26. Mr Fraser Agnew (UUAP) 49. Mr George Savage (UUP) 72. Mr Alex Attwood (SDLP) 95.Mr Conor Murphy (Sinn Féin) 3.Mr Joe Reynolds (Deputy Clerk) 27. Mr Alan McFarland (UUP) 50. Mr Mark Robinson (DUP) 73. Dr Séan Farren (SDLP) 96.Mr David Ford (Alliance) 4. Mr Gerald Colan-O’Leary (Head of Security) 28. Rt Hon David Trimble (UUP) 51. Mr Denis Haughey (SDLP) 74. Mr Paul Berry (DUP) 97.Mr David Ervine (PUP) 5.Mr Jim Shannon (DUP) 29. Mr David McClarty (UUP) 52. Mr Eddie McGrady (SDLP) 75. Mr Fred Cobain (UUP) 98.Mr Billy Hutchinson (PUP) 6. -

Minutes of Proceedings

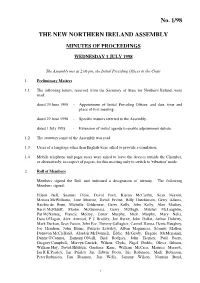

No. 1/98 THE NEW NORTHERN IRELAND ASSEMBLY MINUTES OF PROCEEDINGS WEDNESDAY 1 JULY 1998 The Assembly met at 2.06 pm, the Initial Presiding Officer in the Chair 1. Preliminary Matters 1.1 The following letters, received from the Secretary of State for Northern Ireland, were read: dated 29 June 1998 - Appointment of Initial Presiding Officer, and date, time and place of first meeting. dated 29 June 1998 - Specific matters referred to the Assembly. dated 1 July 1998 - Extension of initial agenda to enable adjournment debate. 1.2 The statutory remit of the Assembly was read. 1.3 Users of a language other than English were asked to provide a translation. 1.4 Mobile telephone and pager users were asked to leave the devices outside the Chamber, or alternatively, in respect of pagers, for this meeting only to switch to ’vibration’ mode. 2. Roll of Members Members signed the Roll and indicated a designation of identity. The following Members signed: Eileen Bell, Seamus Close, David Ford, Kieran McCarthy, Sean Neeson, Monica McWilliams, Jane Morrice, David Ervine, Billy Hutchinson, Gerry Adams, Bairbre de Brun, Michelle Gildernew, Gerry Kelly, John Kelly, Alex Maskey, Barry McElduff, Martin McGuinness, Gerry McHugh, Mitchel McLaughlin, Pat McNamee, Francie Molloy, Conor Murphy, Mick Murphy, Mary Nelis, Dara O’Hagan, Alex Atwood, P J Bradley, Joe Byrne, John Dallat, Arthur Doherty, Mark Durkan, Sean Farren, John Fee, Tommy Gallagher, Carmel Hanna, Denis Haughey, Joe Hendron, John Hume, Patricia Lewsley, Alban Maginness, Séamus Mallon, Donovan McClelland, -

The Northern Ireland Assembly

No. 1/99 NORTHERN IRELAND ASSEMBLY MINUTES OF PROCEEDINGS MONDAY 6 DECEMBER 1999 The Assembly met at 10.30 am, the Presiding Officer in the Chair 1. Personal Prayer or Meditation 1.1 Members observed two minutes’ silence. 2. Statutory Committee Business 2.1 Motion Proposed: That this Assembly confirms ‘MLA’ as designatory letters for Assembly Members. [Mr F Cobain] [Mr D Haughey] After debate, the Question being put, the Motion was carried without division. 2.2 Motion Proposed: After Standing Order 57 insert a new Standing Order: Standing Committee on European Affairs 1. There shall be a Standing Committee of the Assembly to be known as the Standing Committee on European Affairs. 2. It shall consider and review on an ongoing basis: (a) matters referred to it in relation to European Union issues; and (b) any other related matter or matters determined by the Assembly. 199 3. The Committee shall have powers to call for persons and papers. 4. The procedures of the Committee shall be such as the Committee shall determine. [Mr F Cobain] [Mr D Haughey] After debate, the Question being put, the Motion was carried without division. 2.3 Motion Proposed: After Standing Order 57 insert a new Standing Order: Committee on Equality, Human Rights and Community Relations 1. There shall be a Standing Committee of the Assembly to be known as the Equality, Human Rights and Community Relations Committee. 2. It shall consider and review on an ongoing basis: (a) matters referred to it in relation to Equality, Human Rights and Community Relations; and (b) any other related matter or matters determined by the Assembly.