Leverhulme-Funded Monitoring Programme

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Get Involved the Work of the Northern Ireland Assembly

Get Involved The work of the Northern Ireland Assembly Pól Callaghan MLA, Tom Elliott MLA, Gregory Campbell MP MLA and Martina Anderson MLA answer questions on local issues at Magee. Contents We welcome your feedback This first edition of the community We welcome your feedback on the newsletter features our recent Community Outreach programme conference at Magee and a number and on this newsletter. Please let of events in Parliament Buildings. us know what you think by emailing It is a snapshot of the Community [email protected] or by Outreach Programme in the Assembly. calling 028 9052 1785 028 9052 1785 Get Involved [email protected] Get Involved The work of the Northern Ireland Assembly Speaker’s overwhelmingly positive. I was deeply impressed by Introduction how passionately those who attended articulated Representative democracy the interests of their own through civic participation causes and communities. I have spoken to many As Speaker, I have always individuals and I am been very clear that greatly encouraged genuine engagement constituency. The event that they intend to get with the community is at Magee was the first more involved with the essential to the success time we had tried such Assembly as a result. of the Assembly as an a specific approach with effective democratic MLAs giving support and The Community Outreach institution. We know advice to community unit is available to that the decisions and groups including on how support, advise and liaise legislation passed in the to get involved with the with the community and Assembly are best when process of developing voluntary sector. -

Annual Report 2015 -16

Annual Report 2015 -16 Annual Report 2015 -16 1 Annual Report 2015 -16 Annual Report 2015 -16 Table of Contents Foreword 4 Our Vision 6 Mission Statement 7 Corporate Improvement Governance Framework 8-9 Our Council 10 Elected Members 11-14 15 PLACE 15-18 Summary of Key Achievements 2015 -16 PEOPLE 19-22 19 Summary of Key Achievements 2015 -16 PROSPERITY 23-26 23 Summary of Key Achievements 2015 -16 PERFORMANCE 27-29 27 Summary of Key Achievements 2015 -16 Financial Overview 30 Statutory Indicators 31 2 3 Annual Report 2015 -16 Strolling onAnnual Belfast Loughshore Report 2015 -16 Foreword and Introduction Welcome to Antrim and Newtownabbey Borough Council’s first Annual Report on performance for the In combining the two organisations, the Council has taken the opportunity to introduce a new year 2015 -16. In April 2015 we published our Corporate Plan, 2015 - 30 for the newly formed Council operating model, reduce costs, develop its people and improve and expand its services for our and outlined our commitment to delivering the long term vision to become a ‘Prosperous Place, Inspired customers and residents. by our People, and Driven by Ambition’. This Annual Report 2015 -16 provides an overview of the progress made in terms of the four In this inaugural year, we have put in place an ambitious programme, focusing on delivering, improving strategic pillars set out in the Corporate Plan 2015 - 30. It also includes an overview of the and transforming services for the benefit of our customers and ratepayers. We will continue with this Council’s financial performance for 2015 - 16 and provides detail on how we performed against a journey to achieve and excel on our customers and ratepayers behalf. -

<Election Title>

Electoral Office for Northern Ireland Election of Members of the Northern Ireland Assembly for the LAGAN VALLEY Constituency STATEMENT OF PERSONS NOMINATED and NOTICE OF POLL The following persons have been and stand validly nominated: SURNAME OTHER NAMES ADDRESS DESCRIPTION(if any) SUBSCRIBERS Catney Pat Address in Lagan Valley SDLP (Social Democratic JOHN PATRICK DRAKE, MARZENA & Labour Party) AGNIESZKA CZARNECKA, CONOR EOGHAN McNEILL, MARY THERESA McKEEVER, MARY THERESA LOWRY, ROSEMARY ANNE ORR, ANNE MONICA MAGENNIS, BRIDGET MARY MARSDEN, HENRY McGURNAGHAN, MICHAEL FINBAR RICKARD Craig Jonathan Address in Lagan Valley Democratic Unionist Party WILLIAM ALBERT LEATHEM, - D.U.P. JEFFREY MARK DONALDSON, JOHN ANDREW NELSON, MARGARET HENRIETTA TOLERTON, HAROLD TWYNAM McKIBBEN, DAVID JOSEPH CRAIG, SAMUEL PAUL PORTER, JAMES TATE MILLAR, WILLIAM JOHN THOMPSON, JAMES GRAHAM MARTIN Givan Paul Address in Lagan Valley Democratic Unionist Party JEFFREY MARK DONALDSON, - D.U.P. JOHN ANDREW NELSON, MARGARET HENRIETTA TOLERTON, WILLIAM ALBERT LEATHEM, ROBERT JAMES YOUNG, EDWIN CECIL POOTS, ALAN JOSEPH GIVAN, JACQUELINE PATRICIA EVANS, SAMUEL PAUL PORTER, HELEN ROBERTA JEAN K REDDICK Hale Brenda Address in Lagan Valley Democratic Unionist Party JEFFREY MARK DONALDSON, - D.U.P. EDWIN CECIL POOTS, JOHN ANDREW NELSON, PAUL JONATHAN GIVAN, DAVID JONATHAN CRAIG, PAUL STEWART, ALLAN GEORGE EWART, JONATHAN SCOTT CARSON, ELIZABETH VIRTUE GREEN, WILLIAM ALBERT LEATHEM Hill Mark 8 Chestnut Hall Court, Ulster Unionist Party IAN VINCENT, JAMES BAIRD, Maghaberry, -

Page 1 of 2 a Sad and Painful Week

A Sad And Painful Week - Ulster Unionist Party Northern Ireland - For all of u Page 1 of 2 Home Policy Newsrooms Elected Representatives Unionist.TV Join Us Contact Us Europe Text Only 19th March 2009 You are here » Home » Newsrooms » Latest News » General Site last updated 19th March 2009 Search site A Sad And Painful Week Speeches & Articles Go Reflecting on a painful week for Northern Ireland, Ulster Unionist MEP Jim Policing and Justice - Alan McFarland UUP Newsroom Nicholson has stressed the strength of cross- Latest News community and cross-party Northern Ireland Needs Leadership General opposition to dissident republican terrorism. Environment Mr. Nicholson said, "It has been a sad, painful week Text of a speech by Sir Reg Empey to the Health for the people of AGM of the Ulster Unionist Council on Agriculture Northern Ireland. Those of us who lived through the Saturday, May 31, 2008. Troubles hoped that Objectives and Policy such events would never again occur on our streets. Speech by Sir Reg Empey to UUP Annual Objectives We hoped that the Conference Standing up for Northern Ireland generation that came of age after 1998 would never witness what we A Competitive Economy witnessed. Instead, this past week three families have been left grieving because of the actions of evil people. Making a mess of the Maze A Northern Ireland for Everyone Protecting our Environment "Amidst the pain and grief of this week, there have also been signs of Text of a speech to the AGM of the UUP Quality Public Services hope. On Wednesday the people of Northern Ireland in Belfast, Newry, East Antrim Constituency Association. -

Download Minutes

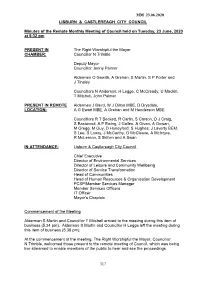

MM 23.06.2020 LISBURN & CASTLEREAGH CITY COUNCIL Minutes of the Remote Monthly Meeting of Council held on Tuesday, 23 June, 2020 at 5:32 pm PRESENT IN The Right Worshipful the Mayor CHAMBER: Councillor N Trimble Deputy Mayor Councillor Jenny Palmer Aldermen O Gawith, A Grehan, S Martin, S P Porter and J Tinsley Councillors N Anderson, H Legge, C McCready, U Mackin, T Mitchell, John Palmer PRESENT IN REMOTE Aldermen J Baird, W J Dillon MBE, D Drysdale, LOCATION: A G Ewart MBE, A Grehan and M Henderson MBE Councillors R T Beckett, R Carlin, S Carson, D J Craig, S Eastwood, A P Ewing, J Gallen, A Givan, A Gowan, M Gregg, M Guy, D Honeyford, S Hughes, J Laverty BEM, S Lee, S Lowry, J McCarthy, G McCleave, A McIntyre, R McLernon, S Skillen and A Swan IN ATTENDANCE: Lisburn & Castlereagh City Council Chief Executive Director of Environmental Services Director of Leisure and Community Wellbeing Director of Service Transformation Head of Communities Head of Human Resources & Organisation Development PCSP/Member Services Manager Member Services Officers IT Officer Mayor’s Chaplain Commencement of the Meeting Alderman S Martin and Councillor T Mitchell arrived to the meeting during this item of business (5.34 pm). Alderman S Martin and Councillor H Legge left the meeting during this item of business (5.36 pm). At the commencement of the meeting, The Right Worshipful the Mayor, Councillor N Trimble, welcomed those present to the remote meeting of Council, which was being live streamed to enable members of the public to hear and see the proceedings. -

A Fresh Start? the Northern Ireland Assembly Election 2016

A fresh start? The Northern Ireland Assembly election 2016 Matthews, N., & Pow, J. (2017). A fresh start? The Northern Ireland Assembly election 2016. Irish Political Studies, 32(2), 311-326. https://doi.org/10.1080/07907184.2016.1255202 Published in: Irish Political Studies Document Version: Peer reviewed version Queen's University Belfast - Research Portal: Link to publication record in Queen's University Belfast Research Portal Publisher rights Copyright 2016 Taylor & Francis. This work is made available online in accordance with the publisher’s policies. Please refer to any applicable terms of use of the publisher. General rights Copyright for the publications made accessible via the Queen's University Belfast Research Portal is retained by the author(s) and / or other copyright owners and it is a condition of accessing these publications that users recognise and abide by the legal requirements associated with these rights. Take down policy The Research Portal is Queen's institutional repository that provides access to Queen's research output. Every effort has been made to ensure that content in the Research Portal does not infringe any person's rights, or applicable UK laws. If you discover content in the Research Portal that you believe breaches copyright or violates any law, please contact [email protected]. Download date:30. Sep. 2021 A fresh start? The Northern Ireland Assembly election 2016 NEIL MATTHEWS1 & JAMES POW2 Paper prepared for Irish Political Studies Date accepted: 20 October 2016 1 School of Sociology, Politics and International Studies, University of Bristol, Bristol, UK. Correspondence address: School of Sociology, Politics and International Studies, University of Bristol, 11 Priory Road, Bristol BS8 1TU, UK. -

Fund Focus Winter 2010

Fund Winter 2010 The Newsletter of the International Fund for Ireland news www.internationalfundforireland.com The International Fund for Ireland announces £12m/€14.4m to promote sharing and integration Following the Fund’s most recent Board continued commitment to bringing together “In building these closer links from meeting in County Antrim on 4 November people from the Unionist and Nationalist primary school age and upwards, 2010, Fund Chairman Dr Denis Rooney traditions, be it in a classroom, on a youth we are trying to foster a greater CBE announced £12m/€14.4m funding programme, in housing or through work understanding of and respect for both to support a wide range of pioneering with local communities. traditions - to live peaceably in a shared community relations initiatives in shared and tolerant society.” education, youth work, community “The Fund is committed to supporting development and re-imaging. projects that seek to dismantle traditional Full details of this latest funding barriers in an effort to create a truly announcement can be viewed Dr Denis Rooney said: “This funding integrated society that will underpin a lasting on our website: www.international announcement demonstrates the Fund’s peace, long after the Fund ceases to exist. fundforireland.com Fund’s Shared Neighbourhood Programme reaches its target The Shared Neighbourhood Programme, working within the 30 neighbourhoods in the which is designed to support and Shared Neighbourhood Programme continue encourage shared neighbourhoods to experience some very real difficulties and across Northern Ireland has achieved its challenges in pursuing the vision for their initial aim of attracting 30 participants communities.” onto the Programme in three years. -

Formal Minutes of the Committee

House of Commons Northern Ireland Affairs Committee Formal Minutes of the Committee Session 2010-12 Formal Minutes of the Committee Tuesday 27 July 2010 Members present: Mr Laurence Robertson, in the Chair1 Oliver Colvile Ian Paisley Mr Stephen Hepburn Stephen Pound Ian Lavery Mel Stride Naomi Long Gavin Williamson Jack Lopresti 1. Declaration of interests Members declared their interests, in accordance with the Resolution of the House of 13 July 1992 (see Appendix A). 2. Committee working methods The Committee considered this matter. Ordered, That the public be admitted during the examination of witnesses unless the Committee otherwise orders. Ordered, That witnesses who submit written evidence to the Committee are authorised to publish it on their own account in accordance with Standing Order No. 135, subject always to the discretion of the Chair or where the Committee orders otherwise. Resolved, That the Committee shall not consider individual cases. Resolved, That the Committee approves the use of electronic equipment by Members during public and private meetings, provided that they are used in accordance with the rules and customs of the House. 3. Future programme The Committee considered this matter. Resolved, That the Committee take evidence from Rt Hon Mr Owen Paterson MP, Secretary of State for Northern Ireland. 1 Elected by the House (S.O. No 122B) 9 June 2010, see Votes and Proceedings 10 June 2010 Resolved, That the Committee take evidence from the Lord Saville of Newdigate, Chair of the Bloody Sunday Inquiry. Resolved, That the Committee inquire into Corporation Tax in Northern Ireland. Resolved, That the Committee visit Northern Ireland. -

Building Government Institutions in Northern Ireland—Strand One Negotiations

BUILDING GOVERNMENT INSTITUTIONS IN NORTHERN IRELAND —STRAND ONE NEGOTIATIONS Deaglán de Bréadún —IMPLEMENTING STRAND ONE Steven King IBIS working paper no. 11 BUILDING GOVERNMENT INSTITUTIONS IN NORTHERN IRELAND —STRAND ONE NEGOTIATIONS Deaglán de Bréadún —IMPLEMENTING STRAND ONE Steven King No. 1 in the lecture series “Institution building and the peace process: the challenge of implementation” organised in association with the Conference of University Rectors in Ireland Working Papers in British-Irish Studies No. 11, 2001 Institute for British-Irish Studies University College Dublin Working Papers in British-Irish Studies No. 11, 2001 © the authors, 2001 ISSN 1649-0304 ABSTRACTS BUILDING GOVERNMENT INSTITUTIONS IN NORTHERN IRELAND —STRAND ONE NEGOTIATIONS The Good Friday Agreement was the culmination of almost two years of multi-party negotiations designed to resolve difficult relationships between the two main com- munities within Northern Ireland, between North and South and between Ireland and Great Britain. The three-stranded approach had already been in use for some time as a format for discussion. The multi-party negotiations in 1997-98 secured Sinn Féin’s reluctant acceptance of a Northern Ireland Assembly, which the party had earlier rejected, as a quid pro quo for significant North-South bodies. Despite the traditional nationalist and republican slogan of “No return to Stormont”, in the negotiations the nationalists needed as much devolution of power as possible if their ministers were to meet counterparts from the Republic on more or less equal terms on the proposed North-South Ministerial Council. Notwithstanding historic tensions between constitutional nationalists and republicans, the SDLP’s success in negotiating a cabinet-style executive, rather than the loose committee structure favoured by unionists, helped ensure there would be a substantial North-South Min- isterial Council, as sought by both wings of nationalism. -

LIST of POSTERS Page 1 of 30

LIST OF POSTERS Page 1 of 30 A hot August night’ feauturing Brush Shiels ‘Oh no, not Drumcree again!’ ‘Sinn Féin women demand their place at Irish peace talks’ ‘We will not be kept down easy, we will not be still’ ‘Why won’t you let my daddy come home?’ 100 years of Trade Unionism - what gains for the working class? 100th anniversary of Eleanor Marx in Derry 11th annual hunger strike commemoration 15 festival de cinema 15th anniversary of hunger strike 15th anniversary of the great Long Kesh escape 1690. Educate not celebrate 1969 - Nationalist rights did not exist 1969, RUC help Orange mob rule 1970s Falls Curfew, March and Rally 1980 Hunger Strike anniversary talk 1980 Hunger-Strikers, 1990 political hostages 1981 - 1991, H-block martyrs 1981 H-block hunger-strike 1981 hunger strikes, 1991 political hostages 1995 Green Ink Irish Book Fair 1996 - the Nationalist nightmare continues 20 years of death squads. Disband the murderers 200,000 votes for Sinn Féin is a mandate 21st annual volunteer Tom Smith commemoration 22 years in English jails 25 years - time to go! Ireland - a bright new dawn of hope and peace 25 years too long 25th anniversary of internment dividedsociety.org LIST OF POSTERS Page 2 of 30 25th anniversary of the introduction of British troops 27th anniversary of internment march and rally 5 reasons to ban plastic bullets 5 years for possessing a poster 50th anniversary - Vol. Tom Williams 6 Chontae 6 Counties = Orange state 75th anniversary of Easter Rising 75th anniversary of the first Dáil Éireann A guide to Irish history -

1 Demographic Change and Conflict in Northern Ireland

Demographic Change and Conflict in Northern Ireland: Reconciling Qualitative and Quantitative Evidence Eric Kaufmann James Fearon and David Laitin (2003) famously argued that there is no connection between the ethnic fractionalisation of a state’s population and its likelihood of experiencing ethnic conflict. This has contributed towards a general view that ethnic demography is not integral to explaining ethnic violence. Furthermore, sophisticated attempts to probe the connection between ethnic shifts and conflict using large-N datasets have failed to reveal a convincing link. Thus Toft (2007), using Ellingsen's dataset for 1945-94, finds that in world-historical perspective, since 1945, ethno-demographic change does not predict civil war. Toft developed hypotheses from realist theories to explain why a growing minority and/or shrinking majority might set the conditions for conflict. But in tests, the results proved inconclusive. These cross-national data-driven studies tell a story that is out of phase with qualitative evidence from case study and small-N comparative research. Donald Horowitz cites the ‘fear of extinction’ voiced by numerous ethnic group members in relation to the spectre of becoming minorities in ‘their’ own homelands due to differences of fertility and migration. (Horowitz 1985: 175-208) Slack and Doyon (2001) show how districts in Bosnia where Serb populations declined most against their Muslim counterparts during 1961-91 were associated with the highest levels of anti-Muslim ethnic violence. Likewise, a growing field of interest in African studies concerns the problem of ‘autochthony’, whereby ‘native’ groups wreak havoc on new settlers in response to the perception that migrants from more advanced or dense population regions are ‘swamping’ them. -

Welcome to the Northern Ireland Assembly

Welcome to the Northern Ireland Assembly MembershipWhat's HappeningCommitteesPublicationsAssembly CommissionGeneral InfoJob OpportunitiesHelp Session 2007/2008 First Report Assembly and Executive review committee Report on the Inquiry into the Devolution of Policing and Justice Matters Volume 2 Written Submissions, Other Correspondence , Party Position Papers, Research Papers, Other Papers Ordered by the Assembly and Executive Review Committee to be printed 26 February 2008 Report: 22/07/08R (Assembly and Executive Review Committee) REPORT EMBARGOED UNTIL Commencement of the debate in Plenary on Tuesday, 11 March 2008 This document is available in a range of alternative formats. http://www.niassembly.gov.uk/assem_exec/2007mandate/reports/report22_07_08R_vol2.htm (1 of 294)02/04/2008 16:04:02 Welcome to the Northern Ireland Assembly For more information please contact the Northern Ireland Assembly, Printed Paper Office, Parliament Buildings, Stormont, Belfast, BT4 3XX Tel: 028 9052 1078 Powers and Membership Powers The Assembly and Executive Review Committee is a Standing Committee established in accordance with Section 29A and 29B of the Northern Ireland Act 1998 and Standing Order 54 which provide for the Committee to: ● consider the operation of Sections 16A to 16C of the Northern Ireland Act 1998 and, in particular, whether to recommend that the Secretary of State should make an order amending that Act and any other enactment so far as may be necessary to secure that they have effect, as from the date of the election of the 2011 Assembly, as if the executive selection amendments had not been made; ● make a report to the Secretary of State, the Assembly and the Executive Committee, by no later than 1 May 2015, on the operation of Parts III and IV of the Northern Ireland Act 1998; and ● consider such other matters relating to the functioning of the Assembly or the Executive as may be referred to it by the Assembly.