Our Obligations to Act Together

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Supply Chain Management of Rations in Indian Army

47 SUPPLY CHAIN MANAGEMENT OF RATIONS IN INDIAN ARMY MINISTRY OF DEFENCE PUBLIC ACCOUNTS COMMITTEE 2011-2012 FORTY-SEVENTH REPORT FIFTEENTH LOK SABHA LOK SABHA SECRETARIAT NEW DELHI FORTY-SEVENTH REPORT PUBLIC ACCOUNTS COMMITTEE (2011-2012) (FIFTEENTH LOK SABHA) SUPPLY CHAIN MANAGEMENT OF RATIONS IN INDIAN ARMY MINISTRY OF DEFENCE Presented to Lok Sabha on 28 December, 2011 Laid in Rajya Sabha on 28 December, 2011 LOK SABHA SECRETARIAT NEW DELHI December, 2011/Pausa, 1933 (Saka) PAC NO. 1956 Price: ` 70.00 ©2011 BY LOK SABHA SECRETARIAT Published under Rule 382 of the Rules of Procedure and Conduct of Business in Lok Sabha (Fourteenth Edition) and Printed by the General Manager, Government of India Press, Minto Road, New Delhi-110 002. CONTENTS PAGE COMPOSITION OF THE PUBLIC ACCOUNTS COMMITTEE (2011-12) ...................... (iii) COMPOSITION OF THE PUBLIC ACCOUNTS COMMITTEE (2010-11) ...................... (V) INTRODUCTION ................................................................................................ (vii) REPORT PART I I. Introductory .......................................................................................... 1 II. Audit Review ....................................................................................... 2 III. Dry Rations (a) Provisioning of Dry Rations ...................................................... 3 (b) Opening Stock Balances Adopted at different levels for Demand Projections Differed Substantially ................................ 9 (c) Procurement of Dry Rations ...................................................... -

John Legend and Salamishah Tillet in Conversation on the Artist's Duty

Apollo Theater Presents John Legend and Salamishah Tillet in Conversation On the Artist’s Duty Wednesday, September 23 at 7pm On Apollo’s Digital Stage “An artist’s duty, as far as I’m concerned, is to reflect the times. I think that is true of painters, sculptors, poets, musicians. As far as I’m concerned, it’s their choice, but I CHOOSE to reflect the times and situations in which I find myself.” – Nina Simone Harlem, NY – September 8, 2020 – On September 23 at 7:00pm ET, the Apollo Theater presents In Conversation: John Legend and Salamishah Tillet. The event will be presented free of charge on the Apollo Digital Stage at www.ApolloTheater.org. Inspired by their mutual role model Nina Simone and her thoughts on the artist’s duty to reflect contemporary issues, Legend and Tillet will discuss art and social justice, the roots of Legend’s activism and what he believes the responsibilities of artists are at this critical moment in American history. For over 86 years, the Apollo has served as an incubator for social and civic advocacy in Harlem, and the Black community at-large. This conversation extends the non-profit Theater’s commitment to using its internationally renowned stage to amplify Black voices and stimulate timely conversations on race and social justice. To RSVP for the program, visit this link. Multiplatinum recording artist, composer, activist, and philanthropist John Legend has been an outspoken champion of civil and human rights. Throughout his life, Legend has been deeply committed to philanthropic efforts, launching several organizations, including the Show Me Campaign, an organization that works to break the cycle of poverty through education. -

Dave Tozer Press Kit (Rev. Jun 21 2010)

Dave Tozer | Press Kit Tozertunes Publishing | [email protected] Biography Dave Tozer is a producer, songwriter and musician. He has worked “Dave Tozer is a with several R&B, Hip-Hop, Rock and Pop artists including John talented, tasteful writer Legend, Jay-Z, Kanye West, Justin Timberlake, John Mayer, and producer with a Natasha Bedingfield, Musiq Soulchild, Estelle, Jazmine musical sensibility that Sullivan and Elliott Yamin. is both distinct and classic. Some of my Hailing from Bridgeton, New Jersey, Tozer taught himself guitar, bass best work has been in and keyboard. After moving to Philadelphia in the late 1990s, Tozer collaboration with Dave, honed his production skills at various Philadelphia-area studios and and I hope to work with began working as a freelance musician playing everything from Hip- him for many years in Hop and Rock to R&B and Pop. Through Max Blumenthal, a mutual the future.” friend, Tozer met University of Pennsylvania student John Stephens John Legend (later Grammy award-winning R&B star John Legend) and began a Recording Artist fruitful, professional relationship. In addition to developing creatively with Legend, Tozer produced his three independently released albums: John Stephens (2000), Live at Jimmy‘s Uptown (2001) and Live at SOB’s (2003). In 2004, Tozer contributed to eight tracks on Legend‘s Grammy Award-winning major label debut Get Lifted and his writing skills garnered him a publishing deal with Viacom-owned Famous Music Publishing. 2005 proved to be an important year for Tozer with the massive success of Get Lifted, which earned eight Grammy nominations and reached multi-platinum status. -

October, 2020

October 2020 The Importance of Voting This November This upcoming Election is one of the most important elections in history. Don’t forget to go to the voting polls November 3rd to cast your ballot. Not only has Donald Trump made his stance clear on immigration and the Black Lives Matter Movement, but his policies have been just as harmful as his Twitter rants. President CLICK HERE TO Trump implemented policies that have actively hurt the READ MORE CLICK HERE TO Read Read black community, such as being disproportionately left out More More from Trump’s tax cuts, rolling back Obama-era guidance on school discipline created to protect black students from severe CLICK HERE TO punishment and much more, according to democrats.org READ MORE CLICK CLICK CLICK HERE TO HERE TO HERE TO CLICK HERE TO READ MORE READ MORE READ MORE Read More Black PR Wire Offers Opportunity for Self-Promotion Promoting yourself, your business or your services is always a good thing. Self promotion enables you to present yourself as competent to other people – able to get the job done effectively. Did you know that there is an entire month dedicated CLICK HERE TO to self-promotion? The idea behind this observanceREAD MORE is that there’s nothing wrong CLICK HERE TO Read Read with being your own best promoter! More More In celebration of Self-Promotion Month, Black PR Wire is offering an exclusive opportunity for those who take a notion to engage in a little self- CLICK HERE TO promotion. All throughout the month of October,READ MORE Black PR Wire will offer a special discount to anyone who distributes a press release through CLICK CLICK CLICK HERE TO HERE TO HERE TO CLICK READ MORE READ MORE READ MORE us. -

American Express Presents

SIX-TIME GRAMMY® WINNER LADY GAGA TO RECEIVE THE JANE ORTNER ARTIST AWARD AT THE GRAMMY MUSEUM®'S 2016 JANE ORTNER EDUCATION AWARD LUNCHEON Event to be Marked by Special Performances from Lady Gaga and GRAMMY® and Oscar Winner John Legend Annual Luncheon Benefitting the Museum's Jane Ortner Education Award Program, Which Encourages Teachers To Utilize Music As A Tool to Enhance the Academic Experience, Will be Held Monday, April 4, 2016 LOS ANGELES (Feb. 5, 2016) — Six-time GRAMMY® Award winner Lady Gaga will be the recipient of the Jane Ortner Artist Award at the GRAMMY Museum®'s 2016 Jane Ortner Education Award Luncheon on April 4, 2016 at Ron Burkle's Green Acres home in Beverly Hills, Calif. The Artist Award honors a performer who has demonstrated passion and dedication to education through the arts. The recipient of this year's Jane Ortner Education Award, which honors K-12 academic teachers who use music in the classroom as a powerful educational tool, will be announced shortly. The luncheon will be marked by special performances from Lady Gaga and nine-time GRAMMY winner and Oscar winner John Legend, the recipient of the Museum's first- ever Jane Ortner Artist Award. Building on the Museum's successful education programs and initiatives, the Jane Ortner Education Award for teachers and the Jane Ortner Artist Award were established by the GRAMMY Museum in partnership with Charles Ortner — entertainment attorney, Museum Board member and husband of the late Jane Ortner, a devoted and beloved public school teacher who valued music as a tool for teaching academic subjects and building confidence and community. -

John Legend Announces 2014 North American Tour “An Evening with John Legend: the All of Me Tour”

For Immediate Release Media Contact: Anne Abrams Charles Zukow Associates 415.296.0677 or [email protected] JOHN LEGEND ANNOUNCES 2014 NORTH AMERICAN TOUR “AN EVENING WITH JOHN LEGEND: THE ALL OF ME TOUR” Legend to play Santa Rosa’s Wells Fargo Center for the Arts April 1, 2014 Exclusive Pre-Sale for Citi Cardmembers Begins January 28; General Public On-sale January 31 at Noon Santa Rosa (January 24, 2014) Nine-time Grammy Award winning artist John Legend has announced dates for his 2014 North American tour titled “An Evening with John Legend: The All of Me Tour.” The tour which begins March 20th in Temecula, CA and goes through early June will feature John in an intimate and acoustic setting, highlighted by guitar/vocal accompaniment as well as a string quartet. The tour will stop at Santa Rosa’s Wells Fargo Center for the Arts on Tuesday, April 1, with an 8 p.m. performance, and other stops on the tour will include a night at the prestigious Disney Concert Hall in Los Angeles, CA on March 26th as well the Brooklyn Academy of Music in Brooklyn, NY on May 31st. Citi cardmembers have access to presale tickets beginning Tuesday, January 28th at 10 a.m.; for more information on how to purchase tickets with a Citi credit card in advance of the public sale, visit www.citiprivatepass.com. Tickets will be available to the general public beginning Friday, January 31 at noon, and can be purchased online at wellsfargocenterarts.org, by calling 707.546.3600, or in person at 50 Mark West Springs Road in Santa Rosa. -

John Legend: Il 19 Giugno Esce Il Nuovo Album "Bigger Love"

GIOVEDì 14 MAGGIO 2020 Uscirà il 19 giugno "Bigger Love", il nuovo album di inediti del poliedrico artista John Legend. John Legend: il 19 giugno esce il nuovo album "Bigger Love" La super star americana, inoltre, domenica 17 maggio sarà ospite in esclusiva di Fabio Fazio a "Che tempo che fa", in prima serata su Rai 2. L'album prende il nome dall'omonimo singolo attualmente in ANTONIO GALLUZZO radio, "Bigger Love", di cui è stato recentemente pubblicato il video diretto da Mishka Kornai. "Il video è stato realizzato per celebrare insieme l'amore, la speranza e la resilienza", racconta Legend. "Stiamo usando la tecnologia per rimanere in contatto e per trovare modi creativi per reagire. Volevamo che il video fosse un grande abbraccio collettivo per tutte le persone nel mondo che [email protected] stanno cercando di rimanere in contatto con la propria famiglia, di SPETTACOLINEWS.IT aiutare i propri vicini o anche semplicemente di trovare un momento di pausa per scatenarsi in un ballo, nonostante il momento folle in cui siamo immersi". I fan da tutte le parti del mondo hanno inviato le loro clip da utilizzare nel video; il risultato è una sorta di viaggio all'insegna di messaggi personali, telefonate e video sui social media di varie persone, che mettono in evidenza i diversi modi in cui si resta connessi gli uni agli altri e con cui si diffonde l'amore in questi tempi così difficili. Scritta da Legend insieme a Ryan Tedder, Zach Skelton e Cautious Clay, "Bigger Love" segue la pubblicazione di "Actions" e di "Conversations In The Dark", entrambi inclusi nel nuovo disco della star internazionale. -

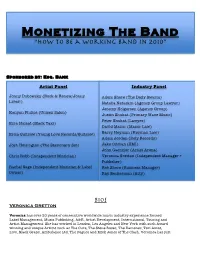

Monetizing the Band “How to Be a Working Band in 2010”

Monetizing The Band “How to be a working band in 2010” Sponsored by: Esq. Bank Artist Panel Industry Panel Jonny Dubowsky (Rock & Renew/Jonny Adam Shore (The Daily Swarm) Lives!) Natalia Nataskin (Agency Group Lawyer) Jeremy Holgersen (Agency Group) Kenyon Philips (Unisex Salon) Justin Shukat (Primary Wave Music) Peter Shukat (Lawyer) Ezra Huleat (Black Taxi) David Mazur (Masur Law) Erica Quitzow (Young Love Records/Quitzow) Barry Heyman (Heyman Law) Adam Jordan (Rely Records) Josh Hoisington (The Stationary Set) Jake Ottman (EMI) John Gaenzler (Artist Arena) Chris Robb (Independent Musician) Veronica Gretton (Independent Manager + Publisher) Rachel Sage (Independent Musician & Label Rob Shore (Business Manager) Owner) Ray Beckerman (Atty) Bios Veronica Gretton Veronica has over 20 years of consecutive worldwide music industry experience Record Label Management, Music Publishing, A&R, Artist Development, International, Touring and Artist Management. She has worked in London, Los Angeles and New York with such Award winning and unique Artists such as The Cure, The Stone Roses, The Ramones, Tori Amos, Live, Black Grape, Ambulance Ltd, The Pogues and Mick Jones of The Clash. Veronica has just launched a new Publishing Company, 401k Music which she will run in tandem with her Artist Management and Music Consultancy Company, Freedom In Exile Josh Hoisington Josh Hoisington has worked in and around the music business for the last decade. After studying music composition and theory at the University of Colorado, he returned to his home state of Michigan to complete his education at Michigan State University. While at MSU, Josh ran POP entertainment, a campus-based organization that booked national touring acts at various campus venues. -

January2019.Pdf

The-Cat’s-Dispatch Are you sticking to your New Year’s resolutions? There’s still time to renew that Planet Fitness subscription! Walnut Ridge, Arkansas Lawrence County School District www.bobcats.k12.ar.us February 6, 2019 Vol. 44 Issue No. 5 ~ Walnut Ridge High School supplement to The Times Dispatch since 1976 ~ Nash & Katie’s Reign Begins The Government Shutdown: By Jordyn Jones What You Need to Know On December 15, Nash of strawberry salad, chicken By Graham West Gill and Katie Kersey were strips, beef brisket, meatballs, declared king and queen of the twice baked potatoes, macaroni On December 22, the any bill that does not provide 2018 Winter Ball. and cheese, rolls, cheese cake, federal government failed to sufficient funding. Winter Ball has been a chocolate cake, and Italian creme agree on the appropriation of This disagreement WRHS tradition since 1984. For cake. funds for the 2019 fiscal year. As affects far more than just the the last three years it has been The music was delivered a result, the government shut border wall situation. Due to held at The Studio on Main by Elite Entertainment, a special down for 35 days, the longest the shutdown national parks Street. thank you to Mrs. Ross who government shutdown in and museums are closed, Mrs. Amanda Haynes hand-picked the judges for the United States history. government employees face catered the meal consisting big night. On January 25th, the reduced or no pay, health federal government reached inspections of food and the a tentative agreement to environment have halted, and temporarily reopen. -

The Mystery of Being Lifted Upwards

The Mystery of the Cross: the mystery of being lifted upwards ‘And I, when I am lifted up from the earth, will draw all people to myself’ (John 12: 32) The Great Lent John 12: 20 – 36 Now there were certain Greeks among those who came up to worship at the feast. Then they came to Philip, who was from Bethsaida of Galilee, and asked him, saying, “Sir, we wish to see Jesus.” Philip came and told Andrew, and in turn Andrew and Philip told Jesus. But Jesus answered them, saying, “The hour has come that the Son of Man should be glorified. Most assuredly, I say to you, unless a grain of wheat falls into the ground and dies, it remains alone; but if it dies, it produces much grain. He who loves his life will lose it, and he who hates his life in this world will keep it for eternal life. If anyone serves Me, let him follow Me; and where I am, there My servant will be also. If anyone serves Me, him My Father will honour. “Now My soul is troubled, and what shall I say? ‘Father, save Me from this hour’? But for this purpose I came to this hour. Father, glorify Your name.” Then a voice came from heaven, saying, “I have both glorified it and will glorify it again.” Therefore the people who stood by and heard it said that it had thundered. Others said, “An angel has spoken to Him.” Jesus answered and said, “This voice did not come because of Me, but for your sake. -

CHRESTO MATHY the Poetry Issue

CHRESTO MATHY Chrestomathy (from the Greek words krestos, useful, and mathein, to know) is a collection of choice literary passages. In the study of literature, it is a type of reader or anthology that presents a sequence of example texts, selected to demonstrate the development of language or literary style The Poetry Issue TOYIA OJiH ODUTOLA WRITING FROM THE SEVENTH GRADE, 2019-2020 THE CALHOUN MIDDLE SCHOOL 1 SADIE HAWKINS Fairy Tale Poem I Am Poem Curses are fickle. You may have heard the story, I am loyal and trusting. Sleeping Beauty, I wonder what next and what now? The royal family births a child I hear songs that aren’t played, An event like this is to be remembered in joy by I see a world beyond ours, all. I want to travel. Yet it was spoiled, I am loyal and trusting, Why, you ask? I pretend to be part of the books I read. The parents, out of fear, made a fatal mistake. I feel happy and sad, They left out one guest. I touch soft fluff. One of the fairies of the forest, I worry about the future, The other three came, all but one. I cry over those lost. When it came for this time for the gifts it I am loyal and trusting happened. I understand things change, This is the story of Maleficent. I say they get better. This is my story. I dream for a better world, I try to understand those around me. It had come, I hope that things will improve, The birth of the heir I am loyal and trusting. -

Academy Award-Winning Artist John Legend to Be Featured Alongside Cirque Du Soleil In

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE March 9, 2015 ACADEMY AWARD-WINNING ARTIST JOHN LEGEND TO BE FEATURED ALONGSIDE CIRQUE DU SOLEIL IN ONE NIGHT FOR ONE DROP MARCH 20 MGM Resorts International presents Third Annual Global Philanthropy Event Imagined by Cirque du Soleil Click to tweet: Oscar winner @JohnLegend gives exclusive performance @cirque #1Night1Drop in #Vegas on 3/20! #DoGoodInVegas Tix/Info: http://cirk.me/1nPIudK LAS VEGAS – One Night for ONE DROP imagined by Cirque du Soleil welcomes R&B recording artist John Legend for an exclusive performance at The Mirage Hotel & Casino Friday, March 20. The Academy Award-winning musician will celebrate World Water Day alongside more than 100 Cirque du Soleil artists in an original, one-night only production created by Mukhtar O.S. Mukhtar. “We are honored to have award-winning musician John Legend featured in One Night for ONE DROP,” said Mukhtar O.S. Mukhtar, creator/director of One Night for ONE DROP. “I admire his innovative approach to music, and his ability to combine different styles and genres seamlessly. His performance will be a huge asset to this unique, once in a lifetime performance.” Legend first broke into the music scene with his debut album Get Lifted, which went platinum and earned him three GRAMMY Awards for Best R&B Album, Best R&B Male Vocal Performance and Best New Artist. Following the album’s success, the R&B icon continued to produce countless hits including “Heaven” and “Green Light.” He has collaborated with a wide array of artists including Lauryn Hill, Alicia Keys, Twista, Janet Jackson and Kanye West.