The Old House Project, St. Andrew's Chapel Boxley, Kent Statement of Significance

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Hythe Ward Hythe Ward

Cheriton Shepway Ward Profile May 2015 Hythe Ward Hythe Ward -2- Hythe Ward Foreword ..........................................................................................................5 Brief Introduction to area .............................................................................6 Map of area ......................................................................................................7 Demographic ...................................................................................................8 Local economy ...............................................................................................11 Transport links ..............................................................................................16 Education and skills .....................................................................................17 Health & Wellbeing .....................................................................................22 Housing .........................................................................................................33 Neighbourhood/community ..................................................................... 36 Planning & Development ............................................................................41 Physical Assets ............................................................................................ 42 Arts and culture ..........................................................................................48 Crime .......................................................................................................... -

'All Wemen in Thar Degree Shuld to Thar Men Subiectit Be': the Controversial Court Career of Elisabeth Parr, Marchioness Of

‘All wemen in thar degree shuld to thar men subiectit be’: The controversial court career of Elisabeth Parr, marchioness of Northampton, c. 1547-1565 Helen Joanne Graham-Matheson, BA, MA. Thesis submitted to UCL for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy 1 Declaration I, Helen Joanne Graham-Matheson confirm that the work presented in this thesis is my own. Where information has been derived from other sources, I confirm that this has been indicated in the thesis. 2 Abstract This thesis reconstructs and analyses the life and agency of Elisabeth Parr, marchioness of Northampton (1526-1565), with the aim of increasing understanding of women’s networks of influence and political engagement at the mid-Tudor courts, c. 1547- 1565. Analysis of Elisabeth’s life highlights that in the absence of a Queen consort the noblewomen of the Edwardian court maintained and utilized access to those in power and those with political significance and authority. During the reign of Mary Tudor, Elisabeth worked with her natal family to undermine Mary’s Queenship and support Elizabeth Tudor, particularly by providing her with foreign intelligence. At the Elizabethan court Elisabeth regained her title (lost under Mary I) and occupied a position as one of the Queen’s most trusted confidantes and influential associates. Her agency merited attention from ambassadors and noblemen as well as from the Emperor Maximilian and King Erik of Sweden, due to the significant role she played in several major contemporary events, such as Elizabeth’s early marriage negotiations. This research is interdisciplinary, incorporating early modern social, political and cultural historiographies, gender studies, social anthropology, sociology and the study of early modern literature. -

George Etheridge, Wyatt's Conspiracy

George Etheridge, Wyatt’s Conspiracy (1557) Homeric Pastiche in Marian England 1. Introduction In Eton College Library resides a curious manuscript poem in Greek hexameters, composed for Queen Mary I (1516–58) by George Etheridge (1519–88), Regius Professor of Greek at Oxford. Completed in 1557, Etheridge’s poem, entitled Συνωμοσία Οὐέτου (hereafter Wyatt’s Conspiracy), survives uniquely in this neglected manuscript: it was never printed, has never been edited, and gives no indication of ever being read.1 Comprising a Latin prose preface and 369 lines of Greek hexameter, Etheridge’s text celebrates the quashing of Sir Thomas Wyatt the Younger’s Rebellion by Mary’s forces in the early months of 1554, reinscribes Etheridge’s allegiance to his royal patron (Mary), and parades his prodigious skill in Greek verse composition in the style of Homer. The poem, reconstructing the rebellion’s brief but climacteric engagements through a series of pseudo-epic set-pieces and imagined speeches, asserts Etheridge’s staunch Catholicism and reaffirms the legitimacy of Mary’s reign against heretical pretenders. It is remarkable not only as an overtly literary treatment of chronicle history sub specie Homeri, but also as a record of the synthetic processes that informed poetic Original orthography of early modern English texts has been lightly modernised: u/v and i/j distinctions are silently normalised, and English scribal contractions are expanded and reproduced as italics. All translations of Latin and Greek are mine, unless otherwise indicated. 1 George Etheridge, Συνωμοσία Οὐέτου [Wyatt’s Conspiracy], Windsor, Eton College Library, MS 148, fols 1r– 38r. -

Allington Castle Conway

http://kentarchaeology.org.uk/research/archaeologia-cantiana/ Kent Archaeological Society is a registered charity number 223382 © 2017 Kent Archaeological Society \ u"*_; <Ak_CL <&__•_ •E!**?f*K- TOff*^ ^ i if •P%% —5** **•"'. • . " ft - . if • i ' _! ' ' •_• .' |• > ' V ''% .; fl y H H i Pko^o.l ALLINGTON CASTLE (A): GENERAL VIEW FROM E. [W. ff.-B. ( 337 ) ALLINGTON CASTLE. BY SIR W. MARTIN CONWAY, M.A., E.S.A. THE immediate neighbourhood of Allington Castle appears to have been a very ancient site of human habitation. It lies close to what must have been an important ford over the Medway, at a point which was approximately the head of low-tide navigation. The road from the east, which debouches on the right bank of the river close beside the present Malta Inn, led straight to the ford, and its continua- tion on the other bank can be traced as a deep furrow through the Lock Wood, and almost as far as the church, though in part it has recently been obliterated by the dejection of quarry debris. This ancient road may be traced up to the Pilgrims' Way, from which it branched off. In the neighbourhood of the castle, at points not exactly recorded, late Celtic burials have been discovered containing remains of the Aylesford type. Where there were burials there was no doubt a settlement. In Roman days the site was likewise well occupied, and the buried ruins of a Roman villa are marked on the ordnance map in the field west of the castle. The site seems to be indicated by a level place on the sloping hill, and when the land in question falls into my hands I propose to make the researches necessary to reveal the situation and character of the villa. -

Edward Hasted the History and Topographical Survey of the County

Edward Hasted The history and topographical survey of the county of Kent, second edition, volume 6 Canterbury 1798 <i> THE HISTORY AND TOPOGRAPHICAL SURVEY OF THE COUNTY OF KENT. CONTAINING THE ANTIENT AND PRESENT STATE OF IT, CIVIL AND ECCLESIASTICAL; COLLECTED FROM PUBLIC RECORDS, AND OTHER AUTHORITIES: ILLUSTRATED WITH MAPS, VIEWS, ANTIQUITIES, &c. THE SECOND EDITION, IMPROVED, CORRECTED, AND CONTINUED TO THE PRESENT TIME. By EDWARD HASTED, Esq. F. R. S. and S. A. LATE OF CANTERBURY. Ex his omnibus, longe sunt humanissimi qui Cantium incolunt. Fortes creantur fortibus et bonis, Nec imbellem feroces progenerant. VOLUME VI. CANTERBURY PRINTED BY W. BRISTOW, ON THE PARADE. M.DCC.XCVIII. <ii> <blank> <iii> TO THOMAS ASTLE, ESQ. F. R. S. AND F. S. A. ONE OF THE TRUSTEES OF THE BRITISH MUSEUM, KEEPER OF THE RECORDS IN THE TOWER, &c. &c. SIR, THOUGH it is certainly a presumption in me to offer this Volume to your notice, yet the many years I have been in the habit of friendship with you, as= sures me, that you will receive it, not for the worth of it, but as a mark of my grateful respect and esteem, and the more so I hope, as to you I am indebted for my first rudiments of antiquarian learning. You, Sir, first taught me those rudiments, and to your kind auspices since, I owe all I have attained to in them; for your eminence in the republic of letters, so long iv established by your justly esteemed and learned pub= lications, is such, as few have equalled, and none have surpassed; your distinguished knowledge in the va= rious records of the History of this County, as well as of the diplomatique papers of the State, has justly entitled you, through his Majesty’s judicious choice, in preference to all others, to preside over the reposi= tories, where those archives are kept, which during the time you have been entrusted with them, you have filled to the universal benefit and satisfaction of every one. -

Sweetinburgharchcant137st Thomas Pageant.Pdf

Canterbury Christ Church University’s repository of research outputs http://create.canterbury.ac.uk Please cite this publication as follows: Sweetinburgh, S. (2016) Looking to the past: the St Thomas Pageant in early Tudor Canterbury. Archaeologia Cantiana, 137. pp. 163-184. ISSN 0066-5894. Link to official URL (if available): This version is made available in accordance with publishers’ policies. All material made available by CReaTE is protected by intellectual property law, including copyright law. Any use made of the contents should comply with the relevant law. Contact: [email protected] Archaeologia Cantiana Vol. 137 2016 LOOKING TO THE PAST: THE ST THOMAS PAGEANT IN EARLY TUDOR CANTERBURY SHEILA SWEETINBURGH From the State Opening of Parliament to the commemoration services and parades to mark historic battles and the beginning and ending of wars, rituals, whether viewed on TV or computer screens, or ‘by being there’, continue to be part of Brit- ish culture as they have been for centuries. What differs, however, are the societies in which ritual takes place, and this is equally the case whether we are looking chronologically and/or geographically. For the historian, therefore, it remains vital to analyse ritual and other related topics in terms of these specifics of time and place. This is not to discount the value of thinking cross-culturally or drawing on theoretical ideas developed in disciplines such as social anthropology and historical geography, but these need to be deployed with caution, and a realisation -

Lower Boxley Road, ME14 Maidstone | Kent Lower Boxley Road, ME14 ME14 2UU £925 Pcm

Lower Boxley Road, ME14 Maidstone | Kent Lower Boxley Road, ME14 ME14 2UU £925 pcm To Let 2 bedroom 1st floor apartment which has been fully refurbished throughout, just 0.9 miles from Maidstone Town Centre. Fully refurbished 1st floor apartment Spacious living room 2 double bedrooms Contemporary kitchen & bathroom Permit on street parking available through Maidstone borough council 0.9 miles from Maidstone town centre 0.3 miles from Maidstone East train station SANDERSONSUK.COM EXPERIENCE THE DIFFERENCE WITH SANDERSONS The Property This spacious two bedroom first floor apartment has been fully refurbished throughout and is just 0.9 miles from Maidstone Town Centre. The good size living room has plenty of pace for both a seating and dining area and opens onto the brand new fitted kitchen which has an oven and four burner hob and space and plumbing for an under counter fridge and a washing machine. There are two double bedrooms and a contemporary bathroom with a matching white suite and a shower over the bath. Permit on street parking is available in the immediate area through Maidstone borough council. Location Maidstone town centre is ranked in the top five shopping centres in the south east of England and with more than one million square feet of retail floor space, in the top 50 in the UK. Much of this space is provided by the two main shopping centres in the town, the Mall plus the Fremlin Walk, which opened in 2006. Other recent developments include the riverside Lockmeadow Centre, which includes a multiplex cinema, restaurants and nightclubs as well as the town's market. -

Item C1 TM/10/2029 – PROPOSED WESTERLY EXTENSION to HERMITAGE QUARRY, HERMITAGE LANE, AYLESFORD, KENT

SECTION C MINERALS AND WASTE DISPOSAL Background Documents - the deposited documents, views and representations received as referred to in the reports and included in the development proposals dossier for each case and also as might be additionally indicated. Item C1 TM/10/2029 – PROPOSED WESTERLY EXTENSION TO HERMITAGE QUARRY, HERMITAGE LANE, AYLESFORD, KENT A report by Head of Planning Applications Group to Planning Applications Committee on 10 May 2011. Planning application TM/10/2029 Proposed westerly extension to Hermitage Quarry, Hermitage Lane, Aylesford, Kent (MR. 717 556) Recommendation: Permission be granted subject to conditions. Local and adjoining Member(s): Mrs T Dean, Mrs P Stockell, Mr P Homewood, Mr D Daley, Mr M Robertson, Mrs V Dagger, Mrs S Hohler and Mr R Long, Classification: Unrestricted Background 1. The existing Hermitage Quarry lies within the strategic gap between Allington, to the east, the village of Aylesford, to the north and Barming Heath to the south. It forms part of 230ha of the Hermitage Farm Estate which comprises agricultural land and woodland as well as the quarry itself. The existing quarry has a purpose built access onto Hermitage Lane (B2246), leading to the A20 and M20 at junction 5. 2. Operational since 1990, the quarry is currently operating within an eastern extension area permitted under planning permission reference TM/05/2784. As part of the overall working plan, the consented phased working and restoration scheme requires the operator to work the site in an east to south direction, with final permitted reserves being worked in the permitted western extension (reference TM/02/2782) before infilling and restoration of the final phase which is currently occupied by the plant site area. -

Anne Boleyn: Whore Or Martyr?

Muhareb 1 Anne Boleyn: Whore or Martyr? An Individual’s Religious Beliefs Shaping the Perception of the Queen of England By Samia Muhareb Senior Thesis in History California State Polytechnic University, Pomona 9 June 2010 Grade: Advisor: Dr. Amanda Podany Muhareb 2 One of the most famous and influential English queen’s who altered society both politically and religiously was Anne Boleyn. The influence Anne Boleyn had on English society in the sixteenth century was summed up by historian Charles Beem, “our biggest enemy is terrorism…theirs was the Reformation. You can't overestimate how traumatic the changes in the church would have been. You might get close if you imagined that Monica Lewinsky had been a radical Islamist and Bill Clinton married her and made everyone convert.”1 Anne Boleyn was not the typical English Rose;2 she had an intense tempting quality that greatly attracted King Henry VIII. She was said to possess a delicate and attractive appearance, a vivacious personality, and exotic features since she was not brought up in the English court but rather the French to serve Queen Claude of France. To Henry, Anne symbolized the sophistication and charm of the French court he so earnestly desired.3 Anne Boleyn was the second wife of Henry VIII after his divorce from Katherine, a divorce that would revolutionize England as the country broke free from the Catholic Church and established the Church of England. Before King Henry VIII married Katherine of Aragon, Katherine was wedded to his elder brother Arthur in 1501. A year after their marriage, Arthur died; but the cause of death remains unknown. -

Congregationalism in Edwardian Hampshire 1901-1914

FAITH AND GOOD WORKS: CONGREGATIONALISM IN EDWARDIAN HAMPSHIRE 1901-1914 by ROGER MARTIN OTTEWILL A thesis submitted to the University of Birmingham for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY Department of History School of History and Cultures College of Arts and Law University of Birmingham May 2015 University of Birmingham Research Archive e-theses repository This unpublished thesis/dissertation is copyright of the author and/or third parties. The intellectual property rights of the author or third parties in respect of this work are as defined by The Copyright Designs and Patents Act 1988 or as modified by any successor legislation. Any use made of information contained in this thesis/dissertation must be in accordance with that legislation and must be properly acknowledged. Further distribution or reproduction in any format is prohibited without the permission of the copyright holder. Abstract Congregationalists were a major presence in the ecclesiastical landscape of Edwardian Hampshire. With a number of churches in the major urban centres of Southampton, Portsmouth and Bournemouth, and places of worship in most market towns and many villages they were much in evidence and their activities received extensive coverage in the local press. Their leaders, both clerical and lay, were often prominent figures in the local community as they sought to give expression to their Evangelical convictions tempered with a strong social conscience. From what they had to say about Congregational leadership, identity, doctrine and relations with the wider world and indeed their relative silence on the issue of gender relations, something of the essence of Edwardian Congregationalism emerges. In their discourses various tensions were to the fore, including those between faith and good works; the spiritual and secular impulses at the heart of the institutional principle; and the conflicting priorities of churches and society at large. -

Draught Copy Distribution List

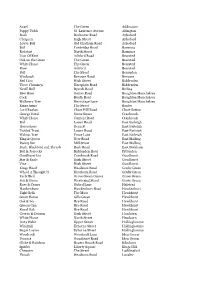

Angel The Green Addington Poppy Fields St. Laurence Avenue Allington Bush Rochester Road Aylesford Chequers High Street Aylesford Lower Bell Old Chatham Road Aylesford Bull Tonbridge Road Barming Redstart North Street Barming Lion Of Kent Ashford Road Bearsted Oak on the Green The Green Bearsted White Horse The Green Bearsted Rose Ashford Bearsted Bull The Street Benenden Woolpack Benover Road Benover Red Lion High Street Biddenden Three Chimneys Hareplain Road Biddenden Nevill Bull Ryarsh Road Birling Beer Barn Sutton Road Boughton Monchelsea Cock Heath Road Boughton Monchelsea Mulberry Tree Hermitage Lane Boughton Monchelsea Kings Arms The Street Boxley Lord Raglan Chart Hill Road Chart Sutton George Hotel Stone Street Cranbrook White Horse Carriers Road Cranbrook Bull Lower Road East Farleigh Horseshoes Dean St East Farleigh Tickled Trout Lower Road East Farleigh Walnut Tree Forge Lane East Farleigh King & Queen New Road East Malling Rising Sun Mill Street East Malling Bush, Blackbird and Thrush Bush Road East Peckham Bell & Jorrocks Biddenden Road Frttenden Goudhurst Inn Cranbrook Road Goudhurst Star & Eagle High Street Goudhurst Vine High Street Goudhurst Kings Head Headcorn Road Grafty Green Who'd A Thought It Headcorn Road Grafty Green Early Bird Grove Green Centre Grove Green Fox & Goose Weavering Street Grove Green Rose & Crown Otford Lane Halstead Hawkenbury Hawkenbury Road Hawkenbury Eight Bells The Moor Hawkhurst Great House Gills Green Hawkhurst Oak & Ivy Rye Road Hawkhurst Queens Inn Rye Road Hawkhurst Royal Oak Rye Road -

The Parish of Durris

THE PARISH OF DURRIS Some Historical Sketches ROBIN JACKSON Acknowledgments I am particularly grateful for the generous financial support given by The Cowdray Trust and The Laitt Legacy that enabled the printing of this book. Writing this history would not have been possible without the very considerable assistance, advice and encouragement offered by a wide range of individuals and to them I extend my sincere gratitude. If there are any omissions, I apologise. Sir William Arbuthnott, WikiTree Diane Baptie, Scots Archives Search, Edinburgh Rev. Jean Boyd, Minister, Drumoak-Durris Church Gordon Casely, Herald Strategy Ltd Neville Cullingford, ROC Archives Margaret Davidson, Grampian Ancestry Norman Davidson, Huntly, Aberdeenshire Dr David Davies, Chair of Research Committee, Society for Nautical Research Stephen Deed, Librarian, Archive and Museum Service, Royal College of Physicians Stuart Donald, Archivist, Diocesan Archives, Aberdeen Dr Lydia Ferguson, Principal Librarian, Trinity College, Dublin Robert Harper, Durris, Kincardineshire Nancy Jackson, Drumoak, Aberdeenshire Katy Kavanagh, Archivist, Aberdeen City Council Lorna Kinnaird, Dunedin Links Genealogy, Edinburgh Moira Kite, Drumoak, Aberdeenshire David Langrish, National Archives, London Dr David Mitchell, Visiting Research Fellow, Institute of Historical Research, University of London Margaret Moles, Archivist, Wiltshire Council Marion McNeil, Drumoak, Aberdeenshire Effie Moneypenny, Stuart Yacht Research Group Gay Murton, Aberdeen and North East Scotland Family History Society,