Seven Challenges the Isle of Man Must Confront in the Near Future

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

1 Gd 2020/0058

GD 2020/0058 2020/21 1 Programme for Government October 2020 – July 2021 Introduction The Council of Ministers is pleased to bring its revised Programme for Government to Tynwald. The Programme for Government was agreed in Tynwald in January 2017, stating our strategic objectives for the term of our administration and the outcomes we hoped to achieve through it. As we enter the final year of this parliament, the world finds itself in the grip of the COVID-19 pandemic. This and other external factors, such as the prospect of a trade agreement between the UK and the EU, will undoubtedly continue to influence the work of Government in the coming months and years. What the Isle of Man has achieved over the past six months, in the face of COVID-19, has been truly remarkable, especially when compared to our nearest neighbours. The collective response of the people of our Island speaks volumes of the strength of our community and has served to remind us of the qualities that make our Island so special. At the beginning of the pandemic the Council of Ministers suspended the Programme for Government, and any work within it, to bring to bear the complete resources of the public service in the fight against coronavirus as we worked to keep our island and its people safe. Through the pandemic we have seen behaviour changes in society and in Government, and unprecedented times seem to have brought unprecedented ways of working. It is important for the future that we learn from the experiences of COVID and carry forward the positive elements of both what was achieved, and how Government worked together to achieve it. -

Actions Reporting

PROGRAMME FOR GOVERNMENT Q1 REPORTING 2017 ACTIONS Actions The Programme for Government ‘Our Island - a special place to live and work’ was approved by Tynwald in January 2017 and in April 2017 a performance framework, ‘Delivering a Programme for Government’, was also approved. The ‘Programme for Government 2016-21’ is a strategic plan that outlines measurable goals for Government. The Council of Ministers have committed to providing a public update against the performance framework on a quarterly basis. This report provides an update on performance through monitoring delivery of the actions committed to. The first quarter for 2017/18 ran April, May, June and reporting for this period has been undertaken during the past 4 weeks. Information has been provided from across Government Departments, Boards and Offices, and the Cabinet Office have collated these to provide this report on Key Performance Indicators. The Programme for Government outlines a number of initial actions that were agreed by the Council of Ministers which will help take Government closer to achieving its overall objectives and outcomes. Departments Boards and Offices have developed action plans to deliver these actions and this report provides an update status report on delivery against these action plans. POLITICAL OUTCOME TITLE Q1 Data Comment SPONSOR Promote and drive the Enterprise Development Fund and Martyn Perkins ensure it is delivering jobs and new businesses for our GREEN We have an economy where Chairman OFT local entrepreneurship is Island supported and thriving -

Newsletter from the West of the Island

Geoffrey Ray Harmer Boot MHK for MHK for Glenfaba & Peel Glenfaba & Peel Minister of Minister of Environment Food Infrastructure & Agriculture (DOI) (DEFA) Tynwald: 01624 685485 Tynwald: 01624 685596 Mobile: 07624 381497 Mobile: 07624 215577 www.geoffreyboot.org Spring 2017 www.rayharmer.im [email protected] [email protected] Glenfaba & Peel Welcome to our first newsletter from the West of the Island. We both gave a commitment during the election to stay in touch, part of that commitment revolved around hard copy newsletters as we are aware that not everyone has access to websites, Facebook and Twitter. Programme for Government One of the most important tasks for any new administration is to put together a Programme for Government for the next five years. In the past this has been a lengthy process, sometimes taking up to 18 months. After the election in September and our appointments to the Council of Ministers, the Chief Minister was determined we echo his sentiments by putting together a programme as quickly as possible but as inclusively as possible. Consultation with all MHKs started almost immediately and there were invitations for participation in the preparation for the programme to interested external parties including businesses. As a result a 100 days after the election the Programme for Government 2016 – 2021 was approved unanimously by Tynwald. The programme is available on this link www.gov.im/media/1354840/ programme-for-government.pdf and it is not our intention to go into great detail in this newsletter but there are three strategic objectives which are overarching aims of the Council of Ministers in the long term and approved by all members. -

P R O C E E D I N G S

T Y N W A L D C O U R T O F F I C I A L R E P O R T R E C O R T Y S O I K O I L Q U A I Y L T I N V A A L P R O C E E D I N G S D A A L T Y N HANSARD S T A N D I N G C O M M I T T E E O F T Y N W A L D O N E C O N O M I C P O L I C Y R E V I E W B I N G V E A Y N T I N V A A L M Y C H I O N E A A S C R U T A G H E Y P O L A S E E Y N T A R M A Y N A G H Douglas, Wednesday, 7th March 2012 PP59/12 EPRC, No. 1 All published Official Reports can be found on the Tynwald website www.tynwald.org.im/Official Papers/Hansards/Please select a year: Reports, maps and other documents referred to in the course of debates may be consulted on application to the Tynwald Library or the Clerk of Tynwald’s Office. Supplementary material subsequently made available following Questions for Oral Answer is published separately on the Tynwald website, www.tynwald.org.im/Official Papers/Hansards/Hansard Appendix Published by the Office of the Clerk of Tynwald, Legislative Buildings, Finch Road, Douglas, Isle of Man, IM1 3PW. -

KPMG Isle of Man Egaming Summit Report

KPMG eGaming Summit Isle of Man September 2017 2 Kindly sponsored by A Word from the Sponsor Once again, we are delighted to be the sponsors of this year’s KPMG Isle of Man eGaming Summit report. The annual summit goes from strength to strength and this year was characterised by an industry call for social responsibility, diversity, and innovation. A hearty embrace of these three key areas is visible across several sectors of the Island’s business community, and undeniably prevalent in eGaming. Indeed, the presence of industry leaders such as Microgaming and The Stars Group plays testament to our values. We at Continent 8 are committed to enhancing the Isle of Man’s position as a pivotal hub on the eGaming world stage, and are proud to call it our home. An unrivalled telecommunications network, empathic public/private sector bond, and growing community of experts, continues to add to our reputation as a premiere eGaming location. We are uniquely placed as the market leader in player fund protection, and in being home to no fewer than six Tier 3+ data centres. Centrally situated in the Island, our world-class data centre constitutes the footprint for a wealth of resources servicing Dublin, Gibraltar, Guernsey, Malta, Milan, Montreal, Paris and Singapore. Continent 8 is proud to have become the most recognised brand for consummate security and reliable services in the eGaming industry. The resilient nature of eGaming means challenges can be met with flex: 2018 promises to be a busy year for the sector. We hope you enjoy this year’s report and look forward to welcoming everyone again at the next summit which KPMG is due to host in Gibraltar on 26 April 2018. -

National Telecommunications Strategy October 2018

NATIONAL TELECOMMUNICATIONS STRATEGY OCTOBER 2018 GD 2018/0062 CONTENTS Foreword 04 Hon. Howard Quayle MHK – Chief Minister Hon. Laurence Skelly MHK – Minister for Enterprise Executive Summary 06 Our Telecommunications Vision 07 The six key strategic themes 08 Why we need a Telecommunications Strategy 09 Theme 1: Making it Happen 10 Theme 2: Regulation and Legislation 12 Theme 3: National Broadband Plan 15 Theme 4: Subsea Cables 22 Theme 5: Planning and Wayleaves 24 Theme 6: Government Operations 26 Summary 28 Conclusion 30 Glossary 31 3 FOREWORD HON. HOWARD QUAYLE, MHK CHIEF MINISTER The Isle of Man Government is determined to support the development of a telecoms infrastructure which meets the needs of both business and the public, now and into the future. We must have this if we are to be an Island of enterprise and opportunity, a special place to live and work. This strategy will support growth supports the economy as a whole. It The Isle of Man can be recognised and productivity and give everyone sends a clear message that the Island once more as being at the forefront the opportunity to engage in a is forward-looking in its approach of telecoms innovation. A fully modern connected world. The and is actively looking to grow digital connected Island with access to need for high speed broadband is a related industries such as Fintech and choice, value and a sustainable question being addressed by every Digital Health. telecommunications infrastructure. developed and many developing countries around the world. It The Island, as an internationally My Government fully supports has been shown that high quality, respected and trusted Crown this strategy and I am determined high speed communications are Dependency, has a long to see it deliver real benefits for essential for economic growth and history of reliable and stable all those who live and work on social inclusion. -

Jersey, Guernsey and the Isle of Man Meet the Rt Hon Penny Mordaunt MP, Before the Next Round of UK-EU Negotiations

Wednesday, 3 June 2020 Jersey, Guernsey and the Isle of Man meet the Rt Hon Penny Mordaunt MP, before the next round of UK-EU negotiations Jersey’s Minister for External Relations, together with the Chief Ministers of Guernsey and the Isle of Man and Guernsey’s Minister for External Relations, has met the Rt Hon Penny Mordaunt MP, the Paymaster General and Minister at the Cabinet Office responsible for representing the Islands’ interests during the UK-EU negotiations. They met on Monday 1 June to discuss the next round of negotiations being held this week. The work to prepare for the negotiations and for the end of the transition period has continued since the UK left the EU on 31 January 2020. Restrictions in place as a result of the COVID-19 pandemic have meant new ways of working remotely and meeting virtually with UK counterparts. This has maintained the pace of these negotiations throughout the last few months as a priority for the UK and the Islands’ governments. In June the UK and EU will hold a High Level Conference to review progress on the negotiations. This week’s meeting with the Rt Hon Penny Mordaunt MP allowed for discussion before this round of negotiations on matters which could affect Jersey, Guernsey and the Isle of Man. The Minister for External Relations, Senator Ian Gorst, said: “These are complex negotiations and in order to maintain and develop our trading relationships with the EU we have worked closely with counterparts in Guernsey and the Isle of Man. We have shared interests and our close working will strengthen our positions for both these EU negotiations, and those the UK will be having on Free Trade Agreements with the rest of the world.” Deputy St Pier, Chief Minister of Guernsey said: “It has been an exceptionally busy few months for all of our Governments and this looks set to continue as we develop and manage our respective economic recovery strategies. -

Mission to Isle of Man 22-23 November 2018

Special Committee on Tax Crimes, Tax Evasion and Tax Avoidance (TAX3) Mission to Isle of Man 22-23 November 2018 PRELIMINARY DRAFT PROGRAMME Thursday, 22 ARRIVAL TO ISLE OF MAN of Members foreseen for November 2018 Thursday afternoon at 15.00 local time (departure from Brussels in the morning). Thursday, 22 November 2018 Time Institution/Host Address/Tel Subject Scenic tour of the Island with a short stop at Tynwald Hill established by the Vikings where the Island’s Parliament, which Pick up from the 15.15 - 16.45 is 1,000 years old, airport annually promulgates the Island’s laws at the Island’s National Day every 5th July. Arrival to hotel for the first meeting Fight against Meeting with money laundering Taxwatch, informal Fight against Isle of Man-based corporate and discussion group on individual tax 17.00 - 18.00 Hotel the topics of tax evasion avoidance and the Transparency of offshore finance beneficial industry ownership VAT Time Institution/Host Address/Tel Subject Fight against money laundering, tax evasion and 18.10 - 19.10 Meeting with Appelby Hotel tax avoidance Transparency of beneficial ownership Checking in at the hotel and transfer to the venue of the dinner (walking distance) Working dinner with Hon Howard Quayle MHK, Chief Minister Hon Alfred Cannan MHK, Minister for the Treasury Hon Laurence Skelly MHK, Minister for Fight against Enterprise money laundering Fight against Mr Will Greenhow, Organised by the corporate and Chief Secretary IoM Government individual tax 20.00 - 22.00 evasion Mr John Quinn, HM Venue -

Office of the Chief Minister 29Th March 2021 Dear Mr

Office of The Chief Minister Oik yn Ard-Shirveishagh Hon Howard Quayle MHK Chief Minister DOUGLAS Isle of Man IM1 3PG British Isles Telephone: +44 (0) 1624 685706 Email: [email protected] 29th March 2021 Dear Mr President, Mr Speaker, Honourable Members During the March 2021 Sitting of Tynwald I made a series of commitments. Firstly, in relation to Urgent Question from the Hon. Member for Arbory, Castletown and Malew, Mr Moorhouse. Mr Moorhouse asked a supplementary question on the testing of the Isle of Man Steam Packet Company (‘IOMSPC’) Crew members and if I knew how many crew members had refused a COVID test (Hansard Ref. 330). As I explained in my response to the supplementary question, this is not a about a refusal at the point of test. The Exemption Certificate, issued to non-resident crew members, includes a condition that the IOMSPC crew members must undertake surveillance testing at the beginning and end of their rostered shift cycle. This is a condition of their entry to the Island and failure to comply is an offence. The Direction Notice issued to IOM resident crew members, requires them to undertake surveillance testing so as to be excluded from self-isolation requirements. If a crew member does not agree to the surveillance testing then they would be required to self-isolate for 21 consecutive days from the date of their arrival back to the Island. Failure to comply is an offence. Secondly, I was asked by Honourable Member for Douglas Central, Mr Thomas, how many COVID cases has the IOMSPC has had over the course of the Pandemic. -

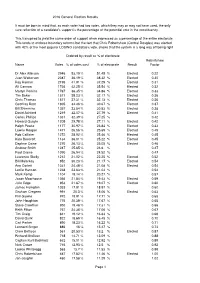

2016 General Election Statistics Summary

2016 General Election Results It must be born in mind that, as each voter had two votes, which they may or may not have used, the only sure reflection of a candidate's support is the percentage of the potential vote in the constituency. This transpired to yield the same order of support when expressed as a percentage of the entire electorate This tends to endorse boundary reforms but the fact that Chris Robertshaw (Central Douglas) was elected with 42% of the most popular LOSING candidate's vote, shows that the system is a long way off being right Ordered by result as % of electorate Robertshaw Name Votes % of votes cast % of electorate Result Factor Dr Alex Allinson 2946 53.19 % 51.45 % Elected 0.22 Juan Watterson 2087 36.19 % 38.32 % Elected 0.30 Ray Harmer 2195 41.91 % 37.29 % Elected 0.31 Alf Cannan 1736 42.25 % 35.54 % Elected 0.32 Martyn Perkins 1767 36.35 % 34.86 % Elected 0.33 Tim Baker 1571 38.23 % 32.17 % Elected 0.36 Chris Thomas 1571 37.31 % 32.13 % Elected 0.36 Geoffrey Boot 1805 34.46 % 30.67 % Elected 0.37 Bill Shimmins 1357 33.54 % 30.53 % Elected 0.38 David Ashford 1219 32.07 % 27.79 % Elected 0.41 Carlos Phillips 1331 32.39 % 27.25 % 0.42 Howard Quayle 1205 29.78 % 27.11 % Elected 0.42 Ralph Peake 1177 30.97 % 26.84 % Elected 0.43 Lawrie Hooper 1471 26.56 % 25.69 % Elected 0.45 Rob Callister 1272 28.92 % 25.46 % Elected 0.45 Kate Beecroft 1134 36.01 % 25.22 % Elected 0.45 Daphne Caine 1270 26.13 % 25.05 % Elected 0.46 Andrew Smith 1247 25.65 % 24.6 % 0.47 Paul Craine 1090 26.94 % 24.52 % 0.47 Laurence Skelly 1212 21.02 -

Department of Economic Development

Department of Economic Development Isle of Man Rheynn Lhiasaghey Tarmaynagh Hon. Laurence Skelly MHK Government Minister for Economic Development Department of Economic Development Refityi. Vrinoliri 1st Floor, St George's Court Upper Church Street Douglas, Isle of Man IM1 1EX Direct Dial No: (01624) 686401 Fax: (01624) 686454 Website: www.gov.im/ded Email: [email protected] 26 June 2015 To: Mr Speaker and Members of the House Of Keys Dear Mr Speaker and Members of the House of Keys Re: House of Keys Sitting 23 June 2015 — Oral Question 5 At this week's sitting of the House of Keys, I responded to the question on Local Regeneration Committees from the Honourable Member for Onchan, Mr Quirk. As part of my response I committed to provide to the Honourable Members details of the wider remit for the Local Regeneration Committees, and details of the assistance to areas outside of Douglas available under the Financial Assistance Scheme. The information is attached in the Annex to this letter. In addition, I have included the full current terms of reference of the Local Regeneration Committees and current membership. Yours sincerely Hon Laurence Skelly MHK Minister for Economic Development Enc. Annex Annex Wider remit of the Local Regeneration Committees The wider remit of the Committees could include matters such as: • Supporting the delivery of Vision 2020 and the Government's economic growth agenda. • Compiling, in conjunction with Government, a baseline of local economic information which includes, employment sectors, employment numbers, unemployment, housing numbers and types, retail information, number of new businesses established, the businesses benefitting from grants, footfall figures and vacant shop unit data. -

Brexit Report: Steps Taken by the Government of Jersey

STATES OF JERSEY BREXIT REPORT: STEPS TAKEN BY THE GOVERNMENT OF JERSEY BEFORE NOTIFICATION BY THE GOVERNMENT OF THE UNITED KINGDOM UNDER ARTICLE 50 OF THE UK’S INTENTION TO WITHDRAW FROM THE EU Lodged au Greffe on 31st January 2017 by the Minister for External Relations STATES GREFFE 2017 P.7 PROPOSITION THE STATES are asked to decide whether they are of opinion (a) to recognise that the Government of the United Kingdom is likely to issue a notice under Article 50 of the Treaty on European Union to withdraw from the European Union; and (b) to endorse the Council of Ministers’ intention to propose the repeal of the European Union (Jersey) Law 1973. MINISTER FOR EXTERNAL RELATIONS Page - 2 P.7/2017 CONTENTS Page Foreword by the Minister for External Relations ............................................ 4 1. INTRODUCTION ................................................................................... 5 2. BACKGROUND ..................................................................................... 5 3. DEVELOPMENTS SINCE THE REFERENDUM ................................ 6 4. WHAT JERSEY HAS DONE SINCE THE REFERENDUM ................ 7 5. WHAT IS JERSEY DOING NEXT? ...................................................... 10 Page - 3 P.7/2017 REPORT Foreword by the Minister for External Relations The Ministry for External Relations and other departments of the Government of Jersey, have been working assiduously to assert the Jersey interests that were identified in our report R.72/2016, presented to the States shortly after the UK’s referendum on EU Membership. This further report not only summarises what we have been doing since 23rd June 2016 to make our interests known and understood, but also identifies the first steps that Jersey will be taking to carry forward the withdrawal process, chief among which will be the repeal of the European Union (Jersey) Law 1973.