Of Slaveholders and Renegades: Semantic Uncertainties in Volodymyr Antonovych's Conversion to Ukrainianness

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Young Narcyza Żmichowska's Reception of Western Cultural

Rocznik Komparatystyczny – Comparative Yearbook – Komparatistisches Jahrbuch 7 (2016) DOI: 10.18276/rk.2016.7-16 Ursula Phillips UCL School of Slavonic and East European Studies (SSEES) With Open Eyes: The Young Narcyza Żmichowska’s Reception of Western Cultural Influences Narcyza Żmichowska (1819–1876) is not a name instantly recognizable outside Poland. In the English-speaking world, however, she is not unknown thanks to research on women’s history, where she is usually discussed in connection with the group of women with whom she was associated in the 1840s known as the Enthu- siasts (Fraisse and Perrot, 1993: 485). It is thanks to the appearance of Grażyna Borkowska’s book in English (2001) that her achievements as a literary author have become better known among Slavists and women’s literature researchers outside Poland. An English translation of Żmichowska’s best known novel Poganka (The Heathen) appeared in 2012 with a substantial introduction placing the work in both its Polish and European contemporary contexts (Żmichowska, 2012). Recently, this novel has featured alongside works by Charlotte Brontë, Daphne du Maurier and others, in a PhD dissertation inspired by psychoanalytic theories of femininity and mirroring, thereby proving her potential for comparative analysis (Naszkowska, 2012). The aim of the current article is to discuss this non-Polish context, and how foreign inspirations made their way into Żmichowska’s work and thinking. Like many other Polish cultural figures, Żmichowska maintained a close con- nection with France, although she never became an émigrée. Her literary activity is a testament nonetheless to how, despite spending more or less her whole life in the partitioned Polish lands, mostly in the Russian partition but also in the 1840s in the Poznań region of the Prussian, she was able to keep abreast of philosophical, political and literary developments in France and Germany and, in the latter part of her life, in Britain, North America, Italy and Scandinavia. -

Studia O Poezji I Prozie Oświecenia Author: Bożena Mazurkowa Citation

Title: Z potrzeby chwili i ku pamięci... : studia o poezji i prozie Oświecenia Author: Bożena Mazurkowa Citation style: Mazurkowa Bożena. (2019). Z potrzeby chwili i ku pamięci... : studia o poezji i prozie Oświecenia. Kraków : Wydawnictwo Uniwersytetu Jagiellońskiego. Wydanie książki dofinansowane ze środków Uniwersytetu Śląskiego w Katowicach. Książka udostępniona w otwartym dostępie na podstawie umowy między Uniwersytetem Śląskim a wydawcą. Książkę możesz pobierać z Repozytorium Uniwersytetu Śląskiego i korzystać z niej w ramach dozwolonego użytku. Aby móc umieścić pliki książki na innym serwerze, musisz uzyskać zgodę wydawcy (możesz jednak zamieszczać linki do książki na serwerze Repozytorium Uniwersytetu Śląskiego). Książka Bożeny Mazurkowej BOŻENA MAZURKOWA ma wymiar monograficzny. Zawarte w niej rozprawy scala naczelna idea skupienia się na faktach literackich z zakresu twórczości publiczno-okolicznościowej i osobisto-okazjonalnej. Wypada stwierdzić, CHWILIZ POTRZEBY I KU PAMIĘCI... że Bożena Mazurkowa doskonale porusza się w obrębie podjętej problematyki i przedstawionym zbiorem wkracza w grono czołowych badaczy oświeceniowej literatury okolicznościowej. Wszystkie rozprawy mają charakter nowatorski, dotyczą materii ważnych, godnych pilnej, dokładnej analizy. Książka Bożeny Mazurkowej BOŻENA MAZURKOWA Z potrzeby chwili i ku pamięci… rozprawy rozprawy Studia o poezji literackie literackie Z POTRZEBY CHWILI i prozie oświecenia w sposób istotny dopełni I KU PAMIĘCI... naszą wiedzę o rzeczywistości społeczno-literackiej tej epoki. -

Conrad's Cracow

Yearbook of Conrad Studies (Poland) Vol. VII 2012, pp. 7–49 doi:10.4467/20843941YC.12.001.0690 CONRAD’S CRACOW Stefan Zabierowski The University of Silesia, Katowice Abstract: This article discusses Joseph Conrad’s links with Cracow, the historic capital of Poland and a major centre of Polish culture. Conrad fi rst came to Cracow in February 1869, accompanied by his father Apollo Korzeniowski, who — after several years of exile in northern Russia — had become gravely ill. Conrad visited the city a second time in the summer of 1914, having accepted an invitation from the young Polish politician Józef Hieronim Retinger, and (not without some dif- fi culty) eventually managed to get himself and his family safely back to Britain after the outbreak of World War I. Both of these sojourns in Cracow played an important role in Conrad’s life — and, one might say, in his creative work as a writer. One of the most vivid memories of his fi rst stay in Cracow was the hero’s funeral given to his father, who had been a victim of tsarist oppression. It was from Cracow that the young Conrad set out for France in order to take up a maritime career in Marseilles. During his second stay in Cracow (and Zakopane) Conrad made the acquaintance of many members of the Polish intellectual elite and took the decision to become actively involved in the cause of Polish independence. Keywords: Cracow, Joseph Conrad, Józef Hieronim Retinger, the Polish Question during WWI 1 If we were to ask ourselves which of the Polish towns in which he had occasion to stay — Warsaw, Lwów or Cracow — exerted a particularly strong infl uence on the shaping of the personality and views of a certain Józef Teodor Konrad Nałęcz- Korzeniowski (known all over the world by his literary pseudonym “Joseph Conrad”), then Cracow would have to come fi rst. -

The Grunwald Trail

n the Grunwald fi elds thousands of soldiers stand opposite each other. Hidden below the protec- tive shield of their armour, under AN INVITATION Obanners waving in the wind, they hold for an excursion along long lances. Horses impatiently tear their bridles and rattle their hooves. Soon the the Grunwald Trail iron regiments will pounce at each other, to clash in a deadly battle And so it hap- pens every year, at the same site knights from almost the whole of Europe meet, reconstructing events which happened over six hundred years ago. It is here, on the fi elds between Grunwald, Stębark and Łodwigowo, where one of the biggest battles of Medieval Europe took place on July . The Polish and Lithuanian- Russian army, led by king Władysław Jagiełło, crushed the forces of the Teutonic Knights. On the battlefi eld, knights of the order were killed, together with their chief – the great Master Ulrich von Jungingen. The Battle of Grunwald, a triumph of Polish and Lithuanian weapons, had become the symbol of power of the common monarchy. When fortune abandoned Poland and the country was torn apart by the invaders, reminiscence of the battle became the inspiration for generations remembering the past glory and the fi ght for national independence. Even now this date is known to almost every Pole, and the annual re- enactment of the battle enjoys great popularity and attracts thousands of spectators. In Stębark not only the museum and the battlefi eld are worth visiting but it is also worthwhile heading towards other places related to the great battle with the Teutonic Knights order. -

Eastern Europe, Literature, Postimperial Difference

Form and Instability 8flashpoints The FlashPoints series is devoted to books that consider literature beyond strictly national and disciplinary frameworks, and that are distinguished both by their historical grounding and by their theoretical and conceptual strength. Our books engage theory without losing touch with history and work historically without falling into uncritical positivism. FlashPoints aims for a broad audience within the humanities and the social sciences concerned with moments of cultural emergence and transformation. In a Benjaminian mode, FlashPoints is interested in how literature contributes to forming new constellations of culture and history and in how such formations function critically and politically in the present. Series titles are available online at http://escholarship.org/uc/flashpoints. series editors: Ali Behdad (Comparative Literature and English, UCLA), Founding Editor; Judith Butler (Rhetoric and Comparative Literature, UC Berkeley), Founding Editor; Michelle Clayton (Hispanic Studies and Comparative Literature, Brown University); Edward Dimendberg (Film and Media Studies, Visual Studies, and European Languages and Studies, UC Irvine), Coordinator; Catherine Gallagher (English, UC Berkeley), Founding Editor; Nouri Gana (Comparative Literature and Near Eastern Languages and Cultures, UCLA); Susan Gillman (Literature, UC Santa Cruz); Jody Greene (Literature, UC Santa Cruz); Richard Terdiman (Literature, UC Santa Cruz) A complete list of titles is on page 222. Form and Instability Eastern Europe, Literature, Postimperial Difference Anita Starosta northwestern university press ❘ evanston, illinois THIS BOOK IS MADE POSSIBLE BY A COLLABORATIVE GRANT FROM THE ANDREW W. MELLON FOUNDATION. Northwestern University Press www.nupress.northwestern.edu Copyright © 2016 by Northwestern University Press. Published 2016. All rights reserved. Digital Printing isbn 978-0-8101-3202-3 paper isbn 978-0-8101-3259-7 cloth Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication data are available from the Library of Congress. -

The Ukrainian Bible and the Valuev Circular of July 18, 1863

Acta Slavica Iaponica, Tomus 28, pp. 1‒21 Articles The Ukrainian Bible and the Valuev Circular of July 18, 1863 Andrii Danylenko On July 18 of 1863, a circular sent by Pёtr Valuev,1 Russia’s minister of internal affairs, to the censorship committees imposed restrictions on Ukraini- an-language publications in the Russian Empire. In accordance with this docu- ment, the Censorship Administration could “license for publication only such books in this language that belong to the realm of fine literature; at the same time, the authorization of books in Little Russian with either spiritual content or intended generally for primary mass reading should be ceased.”2 The gen- esis of this circular, which was incorporated into a later act limiting Ukrainian- language publishing, namely, the so-called Ems Decree of May 18, 1876, has been the focus of numerous studies. Various historians (Fedir Savčenko, David Saunders, Alexei Miller, Ricarda Vulpius) tackled the emergence of the Valuev Circular from various points of view that appear sometimes complementary, sometimes kaleidoscopic, while covering loosely related aspects of the prob- lem. In this paper, the Valuev Circular will be addressed in the context of the appearance of modern translations of the Holy Scriptures into vernacular Ukrainian, thus expanding conventional approaches to the initiation of pro- hibitive measures against the Ukrainian language. ON THE GENESIS OF THE CIRCULAR Among circumstantial theories, premised on some secondary aspects of the genesis of the Valuev Circular, deserving of attention is Remy’s recent at- tempt to treat the appearance of anti-Ukrainian edicts as an incidental intru- sion of the individual into the historical chain of events. -

Venice According… Venice According to Odyniec (And Mickiewicz?) in Romantic Contexts

Czytanie Literatury https://doi.org/10.18778/2299-7458.09.04 Łódzkie Studia Literaturoznawcze 9/2020 ISSN 2299–7458 ANNA KURSKA e-ISSN 2449–8386 Jan Kochanowski University of Kielce 0000-0002-2776-2449 65 VeNICe ACCoRDING… VeNICe Venice According to Odyniec (and Mickiewicz?) in Romantic Contexts SUMMARY This text is a reconstruction of the image of Venice offered in Listy z podróży by Antoni Edward Odyniec. Against the background of Romantic traditions (Byron, Chateaubriand, Shelley, and Radcliffe), I present how the author shaped the portrait of Venice suspended between the Romantic vision of the city/monster (Leviathan) and the ballad-based vision of the city/Siren. I indicate not only the fact that the im- age of Venice was rooted in the sentimental/Romantic stereotype, but I also define to what extent it was formed by the imagined world of Polish nobility, i.e. szlachta. Most of all, however, I am interested in the traces present in Listy z podróży which enable one to uncover Mickiewicz’s influence on how Odyniec shaped the image of Venice. Keywords Adam Mickiewicz, Antoni Edward Odyniec, Venice, Romanticism, journey. Mickiewicz arrived with Odyniec in Venice on 7 October 1829 “at one in the afternoon”; they stayed at the de Luna Inn, from where they moved the very next day to a private apartment at “Ponte dei Dai, Torre Correnta, al. Moro.” Their visit lasted until 20 October and it was recorded by Antoni Edward Odyniec in a fragment of Listy z podróży that he wrote to Julian Korsak and Ignacy Chodźko. His description raises a major question: to what degree © by the author, licensee Łódź University – Łódź University Press, Łódź, Poland. -

NARRATING the NATIONAL FUTURE: the COSSACKS in UKRAINIAN and RUSSIAN ROMANTIC LITERATURE by ANNA KOVALCHUK a DISSERTATION Prese

NARRATING THE NATIONAL FUTURE: THE COSSACKS IN UKRAINIAN AND RUSSIAN ROMANTIC LITERATURE by ANNA KOVALCHUK A DISSERTATION Presented to the Department of Comparative Literature and the Graduate School of the University of Oregon in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy June 2017 DISSERTATION APPROVAL PAGE Student: Anna Kovalchuk Title: Narrating the National Future: The Cossacks in Ukrainian and Russian Romantic Literature This dissertation has been accepted and approved in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Doctor of Philosophy degree in the Department of Comparative Literature by: Katya Hokanson Chairperson Michael Allan Core Member Serhii Plokhii Core Member Jenifer Presto Core Member Julie Hessler Institutional Representative and Scott L. Pratt Dean of the Graduate School Original approval signatures are on file with the University of Oregon Graduate School. Degree awarded June 2017 ii © 2017 Anna Kovalchuk iii DISSERTATION ABSTRACT Anna Kovalchuk Doctor of Philosophy Department of Comparative Literature June 2017 Title: Narrating the National Future: The Cossacks in Ukrainian and Russian Romantic Literature This dissertation investigates nineteenth-century narrative representations of the Cossacks—multi-ethnic warrior communities from the historical borderlands of empire, known for military strength, pillage, and revelry—as contested historical figures in modern identity politics. Rather than projecting today’s political borders into the past and proceeding from the claim that the Cossacks are either Russian or Ukrainian, this comparative project analyzes the nineteenth-century narratives that transform pre- national Cossack history into national patrimony. Following the Romantic era debates about national identity in the Russian empire, during which the Cossacks become part of both Ukrainian and Russian national self-definition, this dissertation focuses on the role of historical narrative in these burgeoning political projects. -

Life Histories of Etnos Theory in Russia and Beyond

A Life Histories of Etnos Theory NDERSON in Russia and Beyond , A , Edited by David G. Anderson, Dmitry V. Arzyutov RZYUTOV and Sergei S. Alymov The idea of etnos came into being over a hundred years ago as a way of understanding the collecti ve identi ti es of people with a common language and shared traditi ons. In AND the twenti eth century, the concept came to be associated with Soviet state-building, and it fell sharply out of favour. Yet outside the academy, etnos-style arguments not A only persist, but are a vibrant part of regional anthropological traditi ons. LYMOV Life Histories of Etnos Theory in Russia and Beyond makes a powerful argument for etnos reconsidering the importance of in our understanding of ethnicity and nati onal ( identi ty across Eurasia. The collecti on brings to life a rich archive of previously EDS unpublished lett ers, fi eldnotes, and photographic collecti ons of the theory’s early proponents. Using contemporary fi eldwork and case studies, the volume shows .) Life Histories of Etnos Theory how the ideas of these ethnographers conti nue to impact and shape identi ti es in various regional theatres from Ukraine to the Russian North to the Manchurian Life Histories of steppes of what is now China. Through writi ng a life history of these collecti vist in Russia and Beyond concepts, the contributors to this volume unveil a world where the assumpti ons of liberal individualism do not hold. In doing so, they demonstrate how noti ons of belonging are not fl eeti ng but persistent, multi -generati onal, and bio-social. -

Conrad and Piłsudski

Yearbook of Conrad Studies (Poland) Vol. IX 2014, pp. 7–22 doi:10.4467/20843941YC.14.001.3073 CONRAD AND PIŁSUDSKI Stefan Zabierowski The University of Silesia, Katowice Abstract: Although there would seem to be no apparent link between the English novelist Joseph Conrad and Marshal Józef Piłsudski, who restored the Polish State after World War I, they did in fact have much in common. Both hailed from the Polish eastern borderlands and both came from patriotic noble families. Both had been nurtured on the Polish Romantic poets – and Słowacki in particular. For both of them the failure of the 1863 January Uprising was a traumatic experience and both of them suffered exile in Russia. However, whereas Conrad did not believe that Poland would ever be able to regain her independence, Piłsudski led a successful armed struggle for the Polish cause, thus earning the writer’s unstinting admiration. Piłsudski for his part took pleasure in reading Conrad’s Lord Jim. Keywords: Polish eastern borderlands, Conrad, Piłsudski, January Uprising, 1863 Uprising, Polish independence. The idea of linking these two names would at fi rst sight appear to be rather far- fetched. Could there have been any real connection between one of the greatest English novelists of the twentieth century and one of the main architects of the resto- ration of the State of Poland in 1918? Could the brilliant amateur military command- er who masterminded the Bezdany mail train robbery of 1908 have had anything in common with the elegant English gentleman who penned The Secret Agent and Under Western Eyes? In actual fact, the differences were far fewer than the similarities and a closer ex- amination of the latter can only enrich our understanding of these two exceptional people. -

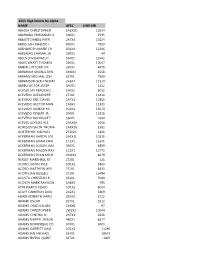

15E5 Ssgt Selects by Alpha

15E5 SSgt Selects by Alpha NAME AFSC LINE-NR ABADIA CHRISTOPHER 2A5X2D 10234 ABARAWA EMMANUEL K 3S0X1 1595 ABBOTT DANIEL PATR 2A7X3 10224 ABDULLAH MALIZIO J 3P0X1 7420 ABENDROTH MARIE CH 00XXX 11386 ABESAMIS CHAMAL JA 2S0X1 44 ABLES LOVIEANGELO 3S0X1 11062 ABLES WYATT THOMAS 2S0X1 10007 ABNER CLIFFORD LEE 3P0X1 4479 ABRAHAM SHARLA DEN 3M0X1 3558 ABRAMS MICHAEL JOH 3E7X1 7500 ABRAMSON SETH NEWM 2A6X4 11510 ABREU VICTOR JOSEP 3P0X1 1412 ACASIO JAY PEROCHO 1P0X1 8032 ACEVEDO ALEXANDER 2T3X1 11416 ACEVEDO ERIC DAVID 2A7X1 12965 ACEVEDO HECTOR MAN 1A0X1 11303 ACEVEDO JANIECE PA 3D0X1 13070 ACEVEDO ROBERT JR 2F0X1 11918 ACEVEDO RODRIGUEZ 3S0X1 2680 ACEVES ULYSSES ALE 2A3X4A 1056 ACHESON SHON THOMA 2A8X2B 5382 ACHTERHOF MICHAEL 2T3X2C 1821 ACKERMAN AARON JOS 2A3X3L 10231 ACKERMAN ADAM CRAI 1C1X1 11641 ACKERMAN LOGAN JAM 3P0X1 8889 ACKERMAN MASON RAY 1C3X1 12772 ACKERMAN RYAN MICH 2M0X3 8079 ACKLEY MARSHALL RY 2T2X1 321 ACORD JUSTIN KYLE 3D1X2 5960 ACORD MATTHEW WILL 2T2X1 5433 ACORN IAN RUSSELL 2T1X1 12494 ACOSTA CHRISTIAN R 3E3X1 7080 ACOSTA MARK RAYMON 2A6X2 495 ACRI MARCO ELIGIO 3D1X2 8009 ACUFF CAMERON DAVI 2A2X1 6869 ADAIR KENNETH HARO 3D0X2 8722 ADAME OSCAR 3E7X1 1512 ADAMS CHAD KALANI 2A6X6 97 ADAMS CHRISTOPHER 2W1X1 10004 ADAMS CYNTHIA N 2A7X3 2658 ADAMS DARRYL JEMON 4B0X1 5627 ADAMS DOMINIQUE CO 3P0X1 3003 ADAMS GARRETT DAVI 3D1X3 11290 ADAMS IAN MICHAEL 3E4X1 10643 ADAMS IRVING QUINT 3E7X1 3407 ADAMS JAMES COLBY 2T3X1 2522 ADAMS JASON ROBERT 1U0X1 7795 ADAMS JOSEPH AARON 2A9X2E 2595 ADAMS KEITH JR 3P0X1 2642 ADAMS KYLE EDWARD 3D0X2 -

Conrad's Footprints

THE MARIA CURIE-SKŁODOWSKA UNIVERSITY – COLUMBIA UNIVERSITY PRESS CONRAD PROJECT CONRAD’S FOOTPRINTS SIXTH INTERNATIONAL JOSEPH CONRAD CONFERENCE CENTRE FOR CONRAD STUDIES, ENGLISH DEPARTMENT MARIA CURIE-SKŁODOWSKA UNIVERSITY, LUBLIN, POLAND Under the Honorary Patronage of The European Parliament and Its President Mr. Martin Schulz LUBLIN: 20-24 JUNE 2016 Organising Committee Centre for Conrad Studies, English Department Maria Curie-Skłodowska University, Lublin Prof. dr hab. Wiesław Krajka (chairman) Dr hab. Katarzyna Sokołowska, Dr Wojciech Kozak Mgr Agata Łukasiewicz, Mgr Dominika Spadło Organizers of session in Lviv Ivan Franko National University of Lviv Maria Curie-Skłodowska University, Lublin Organizers of session in Zhytomyr Zhytomyr Ivan Franko State University Maria Curie-Skłodowska University, Lublin Co-operating Institutions European Parliament Columbia University Press Lublin Province Museum Consulate of the Republic of Poland in Lviv Consulate of the Republic of Poland in Vinnitsa The Organising Committee is honoured to invite .......................................................................... .......................................................................... to CONRAD’S FOOTPRINTS Sixth International Joseph Conrad Conference The conference is organized in honour of East European Monographs, the co-publisher of volumes I-XXII of the series Conrad: Eastern and Western Perspectives, and the staff of Columbia University Press, the distribution agency of all the volumes of the series published so far (I-XXV) The conference is held at the Lublin Province Museum in Lublin, 20 June 2016 The School of Humanities, Maria Curie-Skłodowska University, 21–24 June 2016 The conference also includes two outgoing sessions: at Ivan Franko National University of Lviv on 25 June 2016 and Zhytomyr Ivan Franko State University on 27 June 2016, accompanied by a study tour of Conrad’s footprints in Ukraine 24–29 June 2016 3 Monday, 20 June 2016 10.00 Lublin Province Museum in Lublin The official opening of the conference 1.