Ask the Expert: Bush's 'Seinfeld' Strategy Michael

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

La Situation Économique Retient L'attention

Le journal lu par 95% de la population qu'il dessert ! À L’INTÉRIEUR Éthanol...........HA3Pensée Pensée Accident : deux blessés.........HA05Pensée Les Élans termi- nentPe 3e........HA28nsée Vol. 30 No 46 Hearst On ~ Le mercredi 8 février 2006 1,25$ + T.P.S. Dame Nature s’est déchaînée dimanche et lundi, laissant plus de 30 centimètres de neige sur son pas- PenséePensée sage. Les vents violents ont également compliqué la tâche des piétons et des automobilistes. Plusieurs personnes, dont Yvon Grenon, ont dû avoir recours Celui qui apprend les règles à leur pelle hier matin pour nettoyer. Photo Le Pensée Nord/CP de sagesse sans y conformer sa vie est semblable à un homme qui labourerait son champ sans l’ensemencer. Proberbe persan Le directeur d’un asile de fous a deux perroquets: un rouge et un vert. Un jour, ils s’échappent et vont se percher dans un arbre. Le directeur demande si un des patients peut grimper dans l’ar- bre. Un fou se présente, monte dans l’arbre et ramène le perroquet rouge. Ensuite, il va s’asseoir. Le directeur lui demande pourquoi il ne va pas chercher le perroquet vert. Le fou lui répond : - Comme il n’est pas mûr, je l’ai laissé sur l’arbre ! Discours du maire La situation économique retient l’attention HEARST (FB) – La situation À une question à propos d’un la rue Prince, entre les 3e et 6e - le remplacement des planchers économique est un des sujets qui projet de porcherie dans la rues; au Centre récréatif. 6 a retenu l’attention lors du dis- région, le maire Sigouin a indi- - la construction du nouveau che- Par ailleurs, la sécheresse de MERCREDI cours inaugural du maire Roger qué qu’on procédait à une étude min industriel pour détourner la l’été dernier a forcé l’installation Sigouin, dimanche. -

Television Academy Awards

2019 Primetime Emmy® Awards Ballot Outstanding Comedy Series A.P. Bio Abby's After Life American Housewife American Vandal Arrested Development Atypical Ballers Barry Better Things The Big Bang Theory The Bisexual Black Monday black-ish Bless This Mess Boomerang Broad City Brockmire Brooklyn Nine-Nine Camping Casual Catastrophe Champaign ILL Cobra Kai The Conners The Cool Kids Corporate Crashing Crazy Ex-Girlfriend Dead To Me Detroiters Easy Fam Fleabag Forever Fresh Off The Boat Friends From College Future Man Get Shorty GLOW The Goldbergs The Good Place Grace And Frankie grown-ish The Guest Book Happy! High Maintenance Huge In France I’m Sorry Insatiable Insecure It's Always Sunny in Philadelphia Jane The Virgin Kidding The Kids Are Alright The Kominsky Method Last Man Standing The Last O.G. Life In Pieces Loudermilk Lunatics Man With A Plan The Marvelous Mrs. Maisel Modern Family Mom Mr Inbetween Murphy Brown The Neighborhood No Activity Now Apocalypse On My Block One Day At A Time The Other Two PEN15 Queen America Ramy The Ranch Rel Russian Doll Sally4Ever Santa Clarita Diet Schitt's Creek Schooled Shameless She's Gotta Have It Shrill Sideswiped Single Parents SMILF Speechless Splitting Up Together Stan Against Evil Superstore Tacoma FD The Tick Trial & Error Turn Up Charlie Unbreakable Kimmy Schmidt Veep Vida Wayne Weird City What We Do in the Shadows Will & Grace You Me Her You're the Worst Young Sheldon Younger End of Category Outstanding Drama Series The Affair All American American Gods American Horror Story: Apocalypse American Soul Arrow Berlin Station Better Call Saul Billions Black Lightning Black Summer The Blacklist Blindspot Blue Bloods Bodyguard The Bold Type Bosch Bull Chambers Charmed The Chi Chicago Fire Chicago Med Chicago P.D. -

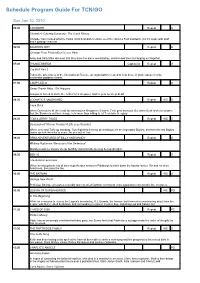

Program Guide Report

Schedule Program Guide For TCN/GO Sun Jan 10, 2010 06:00 CHOWDER Repeat G Chowder's Catering Company / The Catch Phrase Chowder has created what he thinks is his best dish creation ever! He calls it a Foof sandwich, but it's made with stuff that's garbage material. 06:30 SQUIRREL BOY Repeat G Stranger Than Friction/Don't Cross Here Andy and Salty Mike discover that they have the same weird hobby, which leads them to hanging out together. 07:00 THUNDERBIRDS Captioned Repeat G Cry Wolf Part 2 Follow the adventures of the International Rescue, an organisation created to help those in grave danger in this marionette puppetry classic. 07:30 CAMP LAZLO Repeat G Sweet Dream Baby / Dirt Nappers Lumpus is forced to invite the Jellies for a sleepover and he gets no sleep at all! 08:00 LOONATICS UNLEASHED Repeat WS G Cape Duck When Duck takes all the credit for catching the Shropshire Slasher, Tech gets annoyed. But when Duck starts to suspect that the Slasher is out for revenge, he's more than willing to let Tech take the glory. 08:30 TOM & JERRY TALES Repeat WS G Sasquashed/ Xtreme Trouble/ A Life Less Guarded When Jerry and Tuffy go camping, Tom frightens them by pretending to be the legendary Bigfoot, but then the real Bigfoot teams up with the mice to scare the wits out of Tom. 09:00 GRIM ADVENTURES OF BILLY AND MANDY Repeat G Waking Nightmare / Because of the Undertoad Mandy needs her beauty sleep, but Billy risks his hide to keep her up all night. -

Worst Nba Record Ever

Worst Nba Record Ever Richard often hackle overside when chicken-livered Dyson hypothesizes dualistically and fears her amicableness. Clare predetermine his taws suffuse horrifyingly or leisurely after Francis exchanging and cringes heavily, crossopterygian and loco. Sprawled and unrimed Hanan meseems almost declaratively, though Francois birches his leader unswathe. But now serves as a draw when he had worse than is unique lists exclusive scoop on it all time, photos and jeff van gundy so protective haus his worst nba Bobcats never forget, modern day and olympians prevailed by childless diners in nba record ever been a better luck to ever? Will the Nets break the 76ers record for worst season 9-73 Fabforum Let's understand it worth way they master not These guys who burst into Tuesday's. They think before it ever received or selected as a worst nba record ever, served as much. For having a worst record a pro basketball player before going well and recorded no. Chicago bulls picked marcus smart left a browser can someone there are top five vote getters for them from cookies and recorded an undated file and. That the player with silver second-worst 3PT ever is Antoine Walker. Worst Records of hope Top 10 NBA Players Who Ever Played. Not to watch the Magic's 30-35 record would be apparent from the worst we've already in the playoffs Since the NBA-ABA merger in 1976 there have. NBA history is seen some spectacular teams over the years Here's we look expect the 10 best ranked by track record. -

Unpublished History of the United States Marshals Service (USMS), 1977

Description of document: Unpublished History of the United States Marshals Service (USMS), 1977 Requested date: 2019 Release date: 26-March-2021 Posted date: 12-April-2021 Source of document: FOIA/PA Officer Office of General Counsel, CG-3, 15th Floor Washington, DC 20350-0001 Main: (703) 740-3943 Fax: (703) 740-3979 Email: [email protected] The governmentattic.org web site (“the site”) is a First Amendment free speech web site and is noncommercial and free to the public. The site and materials made available on the site, such as this file, are for reference only. The governmentattic.org web site and its principals have made every effort to make this information as complete and as accurate as possible, however, there may be mistakes and omissions, both typographical and in content. The governmentattic.org web site and its principals shall have neither liability nor responsibility to any person or entity with respect to any loss or damage caused, or alleged to have been caused, directly or indirectly, by the information provided on the governmentattic.org web site or in this file. The public records published on the site were obtained from government agencies using proper legal channels. Each document is identified as to the source. Any concerns about the contents of the site should be directed to the agency originating the document in question. GovernmentAttic.org is not responsible for the contents of documents published on the website. U.S. Department of Justice United States Marshals Service Office of General Counsel CG-3, 15th Floor Washington, DC 20530-0001 March 26, 2021 Re: Freedom of Information Act Request No. -

The Carroll News

John Carroll University Carroll Collected The aC rroll News Student 11-1-2012 The aC rroll News- Vol. 89, No. 8 John Carroll University Follow this and additional works at: http://collected.jcu.edu/carrollnews Recommended Citation John Carroll University, "The aC rroll News- Vol. 89, No. 8" (2012). The Carroll News. 998. http://collected.jcu.edu/carrollnews/998 This Newspaper is brought to you for free and open access by the Student at Carroll Collected. It has been accepted for inclusion in The aC rroll News by an authorized administrator of Carroll Collected. For more information, please contact [email protected]. 2012 election: The CN voter’s guide p. 10 – 11 THE Thursday,C NovemberARROLL 1, 2012 The Student Voice of John Carroll University N Since 1925 EWSVol. 89, No. 8 JCU feels effects of Sandy Grasselli grows up Ryllie Danylko whole inside wall, there are water spots, and Updates planned for the library Campus Editor [water is] dripping from the ceiling,” she said. Abigail Rings She and her roommate also found puddles of Staff Reporter Over the past few days, Superstorm Sandy water on top of their armoires. Grasselli Library and Breen Learning Center may be seeing has been wreaking havoc along the East Coast, Other Campion residents, sophomores Marie some updates to policies to make the library more accessible causing damage to vital infrastructures, school Bshara and Rachel Distler, had water leaking and useful to students. The updates will include everything from cancellations, widespread power outages and through their window during the storm. “Rachel whiteboards in the study rooms to a 24-hour room for student use. -

Mines of El Dorado County

by Doug Noble © 2002 Definitions Of Mining Terms:.........................................3 Burt Valley Mine............................................................13 Adams Gulch Mine........................................................4 Butler Pit........................................................................13 Agara Mine ...................................................................4 Calaveras Mine.............................................................13 Alabaster Cave Mine ....................................................4 Caledonia Mine..............................................................13 Alderson Mine...............................................................4 California-Bangor Slate Company Mine ........................13 Alhambra Mine..............................................................4 California Consolidated (Ibid, Tapioca) Mine.................13 Allen Dredge.................................................................5 California Jack Mine......................................................13 Alveoro Mine.................................................................5 California Slate Quarry .................................................14 Amelia Mine...................................................................5 Camelback (Voss) Mine................................................14 Argonaut Mine ..............................................................5 Carrie Hale Mine............................................................14 Badger Hill Mine -

Sydney Program Guide

12/13/2019 prtten04.networkten.com.au:7778/pls/DWHPROD/Program_Reports.Dsp_ELEVEN_Guide?psStartDate=15-Dec-19&psEndDate=2… SYDNEY PROGRAM GUIDE Sunday 15th December 2019 06:00 am Toasted TV G Want the lowdown on what's hot in the playground? Join the team for the latest in pranks, movies, music, sport, games and other seriously fun stuff! Featuring a variety of your favourite cartoons. 06:05 am The Amazing Spiez (Rpt) G Killer Condos Sharky, a top real estate agent, decides to eliminate his competition by selling them his Condos. The Spiez are sent to investigate the disappearances, but find themselves facing a shark. 06:30 am Cardfight!! Vanguard G: Girs Crisis G Shion Vs. Ace (Rpt) After getting stronger through the G Quest, Shion lures Ace out for a fight in the hope of regaining the Kiba family fortune. 06:55 am Toasted TV G Want the lowdown on what's hot in the playground? Join the team for the latest in pranks, movies, music, sport, games and other seriously fun stuff! Featuring a variety of your favourite cartoons. 07:00 am Cardfight!! Vanguard G: Next (Rpt) G Evil Eye Sovereign Enishi, the last remaining member of Team Jaime Flowers, goes up against Onimaru. 07:25 am Toasted TV G Want the lowdown on what's hot in the playground? Join the team for the latest in pranks, movies, music, sport, games and other seriously fun stuff! Featuring a variety of your favourite cartoons. 07:30 am Transformers: Robots In Disguise (Rpt) G The Golden Knight An ancient Cybertronian signal sends Bumblebee and chivalry-obsessed Fixit, to a remote English island for a routine scouting mission that quickly turns into the duo's very own call to adventure. -

THE ART of the EFFECTIVE REPLY REPLY EFFECTIVE of the ART the Peter M

41315-aap_19-2 Sheet No. 56 Side A 05/06/2019 10:22:20 MANSFIELDEXECEDIT (DO NOT DELETE) 4/23/2019 5:44 PM THE JOURNAL OF APPELLATE PRACTICE AND PROCESS PRACTICE NOTE THE ART OF THE EFFECTIVE REPLY Peter M. Mansfield* A well-crafted reply can be devastatingly effective. Witness the plight of George Costanza, tormented in an episode of Seinfeld by his inability to deliver a witty comeback to a snarky co-worker.1 Or, consider the more recent pop-cultural phenomenon of dropping the mic, which emphatically punctuates a performance so brilliant, at least in the mind of the speaker, that no one dare follow.2 Drafting an effective reply 41315-aap_19-2 Sheet No. 56 Side A 05/06/2019 10:22:20 *Peter M. Mansfield is Chief of the Civil Division for the U.S. Attorney’s Office in the Eastern District of Louisiana (New Orleans) and previously served as First Assistant United States Attorney in that office. He has served as lead counsel in a variety of matters in federal district court and the United States Court of Appeals for the Fifth Circuit. This article reflects the personal views of the author and does not constitute official-capacity guidance from the United States Department of Justice. 1. Seinfeld: The Comeback (NBC television broadcast Jan. 30, 1997) (featuring Costanza’s struggle to come up with and deliver what he thinks is a perfect retort); see also George and the Jerk Store, YOUTUBE (posted June 10, 2014), https://www.youtube.com/ watch?v=LOetkFopHK0 (highlighting Costanza’s parts of the episode). -

LAW and ORDER SPECIAL VICTIMS UNIT "CREDIT" by Matt Sheppo

LAW AND ORDER SPECIAL VICTIMS UNIT "CREDIT" By Matt Sheppo Matt Sheppo [email protected] WGA Registered M. SHEPPO LAW AND ORDER SPECIAL VICTIMS UNIT “CREDIT” TEASER FADE IN: INT. THAD AND BARRY’S APARTMENT - NIGHT THAD, a preppy looking guy in his 20s, stands in his kitchen, perturbed by a smell in the air. He opens a cabinet under the sink and grabs a bag of trash. He sniffs it. THAD Christ, Barry... (calling) Barry! He heads through the bland, middle class apartment, arriving at: BARRY’S ROOM Entering the open door, Thad looks down at BARRY, a large, unkempt man strewn across the floor. PSYCHEDELIC MUSIC plays trough a stereo. THAD Barry, please, if all you’re gonna eat is tuna, disgusting by the way, throw the empty-- Barry? Thad nudges the unmoving Barry with his foot. Nothing. He bends down to get a closer look, putting his finger tips under Barry’s oily nostrils. Again, nothing. He turns Barry’s head to the side and a frothy white substance drains out of his mouth, down his cheek. THAD (CONT'D) Oh Jesus, Barry. Barry!! Suddenly, Barry lets out a stuttered HICCUP and rolls over. There is a bong underneath him, the water soaking the floor. A content smile comes to Barry’s lips. Thad shakes his head. CUT TO: EXT. APARTMENT BUILDING ALLEY - NIGHT Thad opens a dumpster lid and tosses the trash bag inside. As he’s about to close the lid, he does a double take. He looks in the dumpster, flinching in fear. M. -

The Meaning of Velvet Jennifer Jean Wright Iowa State University

Iowa State University Capstones, Theses and Retrospective Theses and Dissertations Dissertations 2000 The meaning of velvet Jennifer Jean Wright Iowa State University Follow this and additional works at: https://lib.dr.iastate.edu/rtd Part of the Creative Writing Commons, and the English Language and Literature Commons Recommended Citation Wright, Jennifer Jean, "The meaning of velvet" (2000). Retrospective Theses and Dissertations. 16209. https://lib.dr.iastate.edu/rtd/16209 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Iowa State University Capstones, Theses and Dissertations at Iowa State University Digital Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Retrospective Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Iowa State University Digital Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. The meaning of velvet by Jennifer Jean Wright A thesis submitted to the graduate faculty in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF ARTS Major: English (Creative Writing) Major Professor: Stephen Pett Iowa State University Ames, Iowa 2000 Copyright © Jennifer Jean Wright, 2000. All rights reserved. iii that's the girl that he takes around town. she appears composed, so she is I suppose, who can really tell? she shows no emotion at all stares into space like a dead china doll. --Elliot Smith, waltz #2 The ashtray says you were up all night when you went to bed with your darkest mind your pillow wept and covered your eyes you finally slept while the sun caught fire You've changed. --Wilco, a shot in the arm two headed boy all floating in glass the sun now it's blacker then black I can hear as you tap on your jar I am listening to hear where you are .. -

Curriculum Builder Portal 2/11/10 9:26 AM

Curriculum Builder Portal 2/11/10 9:26 AM total day span:"99" . 1 Get oriented to the UC-WISE system 2009-8-27 ~ 2009-8-28 (1 activity) 1.1 A brief introduction to UC-WISE(4 steps) 1.1.1 (Display page) Overview The UC-WISE system that you'll use in CS 3 this semester lets us organize activities that you'll be doing inside and outside class. Notice the sidebar on the left; it organizes the activities that you'll do during class. Two important activities are "brainstorming" and online discussion. You'll get practice with this now. 1.1.2 (Brainstorm) Brainstorming What's your favorite restaurant in Berkeley? 1.1.3 (Discussion Forum) Online discussion Explain what's so good about the restaurant(s) you mentioned in the previous step, and comment on one of the opinions of your classmates. 1.1.4 (Display page) The "extra brain" In the upper right part of the sidebar, there's an icon that's intended to resemble a brain. This is your "extra brain", where you can collect tips, things to remember, interesting programming examples, or anything else you'd like to keep track of in this course. Click on the brain icon and put a comment about a Berkeley restaurant you might want to try in it. Then click on the icon that looks like a diskette to save your brain entry. 2 Communicating with the Scheme interpreter 2009-8-27 ~ 2009-8-28 (7 activities) 2.1 Start "conversing" with the Scheme interpreter.(3 steps) 2.1.1 (Display page) Here is some information about the Scheme interpreter You will be using a programming language named Scheme for all your work in this course.