Testimony Before the U.S.-China Economic and Security Review Commission

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The China Quarterly Satisfaction with the Standard of Living in Reform

The China Quarterly http://journals.cambridge.org/CQY Additional services for The China Quarterly: Email alerts: Click here Subscriptions: Click here Commercial reprints: Click here Terms of use : Click here Satisfaction with the Standard of Living in Reform Era China Chunping Han The China Quarterly / FirstView Article / February 2013, pp 1 22 DOI: 10.1017/S0305741012001233, Published online: 07 December 2012 Link to this article: http://journals.cambridge.org/abstract_S0305741012001233 How to cite this article: Chunping Han Satisfaction with the Standard of Living in ReformEra China. The China Quarterly, Available on CJO 2012 doi:10.1017/S0305741012001233 Request Permissions : Click here Downloaded from http://journals.cambridge.org/CQY, IP address: 139.82.115.34 on 01 Mar 2013 1 Satisfaction with the Standard of Living in Reform-Era China* Chunping Han† Abstract Popular satisfaction with current standards of living in reform-era China is explored in this article, using survey data from the 2004 China Inequality and Distributive Justice Project. Three major patterns are found: first, people of rural origin, with low levels of education and living in the west region, who are disadvantaged in the inequality hierarchy, report greater sat- isfaction with current standards of living than do privileged urbanites, the highly educated and residents in the coastal east. Second, inequality-related negative life experiences and social cognitive processes including temporal and social comparisons, material aspirations, and life goal orientations med- iate the effects of socioeconomic characteristics. Third, the social sources of satisfaction with current standards of living vary across urban, rural and migrant residents. It is suggested that these patterns have largely stemmed from the unique political economic institutional arrangement and stratifica- tion system in China. -

Hong Kong SAR

China Data Supplement November 2006 J People’s Republic of China J Hong Kong SAR J Macau SAR J Taiwan ISSN 0943-7533 China aktuell Data Supplement – PRC, Hong Kong SAR, Macau SAR, Taiwan 1 Contents The Main National Leadership of the PRC 2 LIU Jen-Kai The Main Provincial Leadership of the PRC 30 LIU Jen-Kai Data on Changes in PRC Main Leadership 37 LIU Jen-Kai PRC Agreements with Foreign Countries 47 LIU Jen-Kai PRC Laws and Regulations 50 LIU Jen-Kai Hong Kong SAR 54 Political, Social and Economic Data LIU Jen-Kai Macau SAR 61 Political, Social and Economic Data LIU Jen-Kai Taiwan 65 Political, Social and Economic Data LIU Jen-Kai ISSN 0943-7533 All information given here is derived from generally accessible sources. Publisher/Distributor: GIGA Institute of Asian Affairs Rothenbaumchaussee 32 20148 Hamburg Germany Phone: +49 (0 40) 42 88 74-0 Fax: +49 (040) 4107945 2 November 2006 The Main National Leadership of the PRC LIU Jen-Kai Abbreviations and Explanatory Notes CCP CC Chinese Communist Party Central Committee CCa Central Committee, alternate member CCm Central Committee, member CCSm Central Committee Secretariat, member PBa Politburo, alternate member PBm Politburo, member Cdr. Commander Chp. Chairperson CPPCC Chinese People’s Political Consultative Conference CYL Communist Youth League Dep. P.C. Deputy Political Commissar Dir. Director exec. executive f female Gen.Man. General Manager Gen.Sec. General Secretary Hon.Chp. Honorary Chairperson H.V.-Chp. Honorary Vice-Chairperson MPC Municipal People’s Congress NPC National People’s Congress PCC Political Consultative Conference PLA People’s Liberation Army Pol.Com. -

Charitable Crowdfunding in China: an Emergent Channel for Setting Policy Agendas? Kellee S

936 Charitable Crowdfunding in China: An Emergent Channel for Setting Policy Agendas? Kellee S. Tsai* and Qingyan Wang†,‡ Abstract Social media in China has not only become a popular means of communi- cation, but also expanded the interaction between the government and online citizens. Why have some charitable crowdfunding campaigns had agenda-setting influence on public policy, while others have had limited or no impact? Based on an original database of 188 charitable crowdfunding projects currently active on Sina Weibo, we observe that over 80 per cent of long-term campaigns do not have explicit policy aspirations. Among those pursuing policy objectives, however, nearly two-thirds have had either agenda-setting influence or contributed to policy change. Such cam- paigns complement, rather than challenge existing government priorities. Based on field interviews (listed in Appendix A), case studies of four micro-charities – Free Lunch for Children, Love Save Pneumoconiosis, Support Relief of Rare Diseases, and Water Safety Program of China – are presented to highlight factors that contributed to their variation in public outcomes at the national level. The study suggests that charitable crowd- funding may be viewed as an “input institution” in the context of responsive authoritarianism in China, albeit within closely monitored parameters. Keywords: social media; charitable crowdfunding; China; agenda-setting; policy advocacy; responsive authoritarianism We should be fully aware of the role of the internet in national management and social governance. (Xi Jinping, 2016) The use of social media helps reduce costs for …resource-poor grassroots organizations without hurting their capacities to publicize their projects and increase their social influence, credibility and legitimacy. -

Xi Jinping's War on Corruption

University of Mississippi eGrove Honors College (Sally McDonnell Barksdale Honors Theses Honors College) 2015 The Chinese Inquisition: Xi Jinping's War on Corruption Harriet E. Fisher University of Mississippi. Sally McDonnell Barksdale Honors College Follow this and additional works at: https://egrove.olemiss.edu/hon_thesis Part of the Political Science Commons Recommended Citation Fisher, Harriet E., "The Chinese Inquisition: Xi Jinping's War on Corruption" (2015). Honors Theses. 375. https://egrove.olemiss.edu/hon_thesis/375 This Undergraduate Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Honors College (Sally McDonnell Barksdale Honors College) at eGrove. It has been accepted for inclusion in Honors Theses by an authorized administrator of eGrove. For more information, please contact [email protected]. The Chinese Inquisition: Xi Jinping’s War on Corruption By Harriet E. Fisher A thesis presented in partial fulfillment of the requirements for completion Of the Bachelor of Arts degree in International Studies at the Croft Institute for International Studies and the Sally McDonnell Barksdale Honors College The University of Mississippi University, Mississippi May 2015 Approved by: ______________________________ Advisor: Dr. Gang Guo ______________________________ Reader: Dr. Kees Gispen ______________________________ Reader: Dr. Peter K. Frost i © 2015 Harriet E. Fisher ALL RIGHTS RESERVED ii For Mom and Pop, who taught me to learn, and Helen, who taught me to teach. iii Acknowledgements I am indebted to a great many people for the completion of this thesis. First, I would like to thank my advisor, Dr. Gang Guo, for all his guidance during the thesis- writing process. His expertise in China and its endemic political corruption were invaluable, and without him, I would not have had a topic, much less been able to complete a thesis. -

China's Domestic Politics and Foreign Policy After the 19Th Party Congress

China's Domestic Politics and Foreign Policy after the 19th Party Congress Paper presented to Japanese Views on China and Taiwan: Implications for U.S.-Japan Alliance March 1, 2018 Center for Strategic & International Studies Washington, D.C. Akio Takahara Professor of Contemporary Chinese Politics The Graduate School of Law and Politics, The University of Tokyo Abstract At the 19th Party Congress Xi Jinping proclaimed the advent of a new era. With the new line-up of the politburo and a new orthodox ideology enshrined under his name, he has successfully strengthened further his power and authority and virtually put an end to collective leadership. However, the essence of his new “thought” seems only to be an emphasis of party leadership and his authority, which is unlikely to deliver and meet the desires of the people and solve the contradiction in society that Xi himself acknowledged. Under Xi’s “one-man rule”, China’s external policy could become “soft” and “hard” at the same time. This is because he does not have to worry about internal criticisms for being weak-kneed and also because his assertive personality will hold sway. Introduction October 2017 marked the beginning of the second term of Xi Jinping's party leadership, following the 19th National Congress of the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) and the First Plenary Session of the 19th Central Committee of the CCP. Although the formal election of the state organ members must wait until the National People's Congress to be held in March 2018, the appointees of major posts would already have been decided internally by the CCP. -

Continuing Crackdown in Inner Mongolia

CONTINUING CRACKDOWN IN INNER MONGOLIA Human Rights Watch/Asia (formerly Asia Watch) CONTINUING CRACKDOWN IN INNER MONGOLIA Human Rights Watch/Asia (formerly Asia Watch) Human Rights Watch New York $$$ Washington $$$ Los Angeles $$$ London Copyright 8 March 1992 by Human Rights Watch All rights reserved. Printed in the United States of America. ISBN 1-56432-059-6 Human Rights Watch/Asia (formerly Asia Watch) Human Rights Watch/Asia was established in 1985 to monitor and promote the observance of internationally recognized human rights in Asia. Sidney Jones is the executive director; Mike Jendrzejczyk is the Washington director; Robin Munro is the Hong Kong director; Therese Caouette, Patricia Gossman and Jeannine Guthrie are research associates; Cathy Yai-Wen Lee and Grace Oboma-Layat are associates; Mickey Spiegel is a research consultant. Jack Greenberg is the chair of the advisory committee and Orville Schell is vice chair. HUMAN RIGHTS WATCH Human Rights Watch conducts regular, systematic investigations of human rights abuses in some seventy countries around the world. It addresses the human rights practices of governments of all political stripes, of all geopolitical alignments, and of all ethnic and religious persuasions. In internal wars it documents violations by both governments and rebel groups. Human Rights Watch defends freedom of thought and expression, due process and equal protection of the law; it documents and denounces murders, disappearances, torture, arbitrary imprisonment, exile, censorship and other abuses of internationally recognized human rights. Human Rights Watch began in 1978 with the founding of its Helsinki division. Today, it includes five divisions covering Africa, the Americas, Asia, the Middle East, as well as the signatories of the Helsinki accords. -

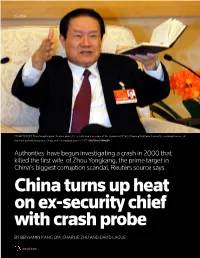

China Turns up Heat on Ex-Security Chief with Crash Probe

CHINA PRIME TARGET: Zhou Yongkang was head of domestic security and a member of the Communist Party Standing Politburo Committee, making him one of the most powerful people in China, until he stepped down in 2012. REUTERS/STRINGER Authorities have begun investigating a crash in 2000 that killed the first wife of Zhou Yongkang, the prime target in China’s biggest corruption scandal, Reuters source says. China turns up heat on ex-security chief with crash probe BY BENJAMIN KANG LIM, CHARLIE ZHU AND DAVID LAGUE SPECIAL REPORT 1 CHINA’S POWER STRUGGLE BEIJING/HONG KONG, SEPTEMBER 12, 2014 ittle is known about the exact circum- stances in which Wang Shuhua was Lkilled. What has been reported, in the Chinese media, is that she died in a road ac- cident sometime in 2000, shortly after she was divorced from her husband. And that at least one vehicle with a military license plate may have been involved in the crash. Fourteen years later, investigators are looking into her death. Their sudden inter- est has nothing to do with Wang herself. It has to do with the identity of her ex-hus- band – once one of China’s most powerful men and now the prime target in President Xi Jinping’s anti-corruption campaign. Investigators are probing the death of the first wife of Zhou Yongkang, China’s HUNTING TIGERS: President Xi Jinping has launched the biggest corruption crackdown since the retired security czar, a source with di- communists came to power in 1949, going after “tigers” or high-ranking officials as well as “flies”. -

Elite Politics and the Fourth Generation of Chinese Leadership

Elite Politics and the Fourth Generation of Chinese Leadership ZHENG YONGNIAN & LYE LIANG FOOK* The personnel reshuffle at the 16th National Congress of the Chinese Communist Party is widely regarded as the first smooth and peaceful transition of power in the Party’s history. Some China observers have even argued that China’s political succession has been institutionalized. While this paper recognizes that the Congress may provide the most obvious manifestation of the institutionalization of political succession, this does not necessarily mean that the informal nature of politics is no longer important. Instead, the paper contends that Chinese political succession continues to be dictated by the rule of man although institutionalization may have conditioned such a process. Jiang Zemin has succeeded in securing a legacy for himself with his “Three Represents” theory and in putting his own men in key positions of the Party and government. All these present challenges to Hu Jintao, Jiang’s successor. Although not new to politics, Hu would have to tread cautiously if he is to succeed in consolidating power. INTRODUCTION Although the 16th Chinese Communist Party (CCP) Congress ended almost a year ago, the outcomes and implications of the Congress continue to grip the attention of China watchers, including government leaders and officials, academics and businessmen. One of the most significant outcomes of the Congress, convened in Beijing from November 8-14, 2002, was that it marked the first ever smooth and peaceful transition of power since the Party was formed more than 80 years ago.1 Neither Mao Zedong nor Deng Xiaoping, despite their impeccable revolutionary credentials, successfully transferred power to their chosen successors. -

Journal of Current Chinese Affairs

China Data Supplement March 2008 J People’s Republic of China J Hong Kong SAR J Macau SAR J Taiwan ISSN 0943-7533 China aktuell Data Supplement – PRC, Hong Kong SAR, Macau SAR, Taiwan 1 Contents The Main National Leadership of the PRC ......................................................................... 2 LIU Jen-Kai The Main Provincial Leadership of the PRC ..................................................................... 31 LIU Jen-Kai Data on Changes in PRC Main Leadership ...................................................................... 38 LIU Jen-Kai PRC Agreements with Foreign Countries ......................................................................... 54 LIU Jen-Kai PRC Laws and Regulations .............................................................................................. 56 LIU Jen-Kai Hong Kong SAR ................................................................................................................ 58 LIU Jen-Kai Macau SAR ....................................................................................................................... 65 LIU Jen-Kai Taiwan .............................................................................................................................. 69 LIU Jen-Kai ISSN 0943-7533 All information given here is derived from generally accessible sources. Publisher/Distributor: GIGA Institute of Asian Studies Rothenbaumchaussee 32 20148 Hamburg Germany Phone: +49 (0 40) 42 88 74-0 Fax: +49 (040) 4107945 2 March 2008 The Main National Leadership of the -

China's Domestic Politicsand

China’s Domestic Politics and Foreign Policies and Major Countries’ Strategies toward China edited by Jung-Ho Bae and Jae H. Ku China’s Domestic Politics and Foreign Policies and Major Countries’ Strategies toward China 1SJOUFE %FDFNCFS 1VCMJTIFE %FDFNCFS 1VCMJTIFECZ ,PSFB*OTUJUVUFGPS/BUJPOBM6OJGJDBUJPO ,*/6 1VCMJTIFS 1SFTJEFOUPG,*/6 &EJUFECZ $FOUFSGPS6OJGJDBUJPO1PMJDZ4UVEJFT ,*/6 3FHJTUSBUJPO/VNCFS /P "EESFTT SP 4VZVEPOH (BOHCVLHV 4FPVM 5FMFQIPOF 'BY )PNFQBHF IUUQXXXLJOVPSLS %FTJHOBOE1SJOU )ZVOEBJ"SUDPN$P -UE $PQZSJHIU ,*/6 *4#/ 1SJDF G "MM,*/6QVCMJDBUJPOTBSFBWBJMBCMFGPSQVSDIBTFBUBMMNBKPS CPPLTUPSFTJO,PSFB "MTPBWBJMBCMFBU(PWFSONFOU1SJOUJOH0GGJDF4BMFT$FOUFS4UPSF 0GGJDF China’s Domestic Politics and Foreign Policies and Major Countries’ Strategies toward China �G 1SFGBDF Jung-Ho Bae (Director of the Center for Unification Policy Studies at Korea Institute for National Unification) �G *OUSPEVDUJPO 1 Turning Points for China and the Korean Peninsula Jung-Ho Bae and Dongsoo Kim (Korea Institute for National Unification) �G 1BSUEvaluation of China’s Domestic Politics and Leadership $IBQUFS 19 A Chinese Model for National Development Yong Shik Choo (Chung-Ang University) $IBQUFS 55 Leadership Transition in China - from Strongman Politics to Incremental Institutionalization Yi Edward Yang (James Madison University) $IBQUFS 81 Actors and Factors - China’s Challenges in the Crucial Next Five Years Christopher M. Clarke (U.S. State Department’s Bureau of Intelligence and Research-INR) China’s Domestic Politics and Foreign Policies -

Rise of Totalitarianism Ch

RISE OF TOTALITARIANISM CH. 14.1-Revolutions in Russia Objective Review 1. What led to the Russian Revolution? 2. What was the March Revolution? 3. What were Lenin’s reforms? Bolshevik Revolution • Lenin returns: Lenin in disguise, Petrograd, April 1917 w/o beard – Germany knows Lenin would stir unrest • Hurt Russian war effort • Returns in armored RR car, under German protection –* “Peace, Land, and Bread” Bolsheviks in Power • Red Guard – Armed Bolshevik enforcers • Arrest Provisional govt. officials, later disappear… • Royal family Murdered • * Russians support Bolsheviks -Call for Immediate peace with the Germans in WWI – Peasants receive farmland – Workers control factories – March 1918 sign Treaty of Brest-Litovsk Civil War Rages in Russia 1918-1920 • Red Army 1920 Lenin cleanses the earth – Bolsheviks • Vladimir Lenin is leader – Leon Trotsky military genius – Joseph Stalin political genius • White Army – Any one who was not a Bolshevik – Western nations, U.S. (sent aid) • Bolsheviks victorious • 14 million die (Due to Revolution) Lenin Restores Order • Lenin needs to restore industry • 1921 New Economic Policy (NEP) – Major industries, banks, ran by the state – Some small businesses, foreign investment encouraged – 1928 econ. back to pre- WWI levels Political Reforms • Nationalism seen as a threat Karl Marx 1818-1883 – Russia organized into small, self ran republics Known as: Union of Soviet Socialist Republics AKA: USSR, or Soviet Union • Bolshevik party becomes the Communist Party – Idea from Karl Marx – Est. dictatorship of the Communist Party not of the proletariat like Marx said Stalin Becomes dictator • 1922 Lenin suffers Leon Trotsky stroke – Who will take power? • Trotsky or Stalin • 1922-1929 struggle Joseph Stalin ensues – 1929 Stalin (political genius) forces Trotsky into exile – Stalin becomes leader (dictator) ET FINISH ALL NOTES 55…#13…BUT WAIT FOR MORE INSTRUCTIONS! Totalitarianism Chapter 14, Section 2 What is Totalitarianism? • A government that takes total control over every aspect of public and private life. -

The Communist Party's Strategy for Dealing With

2nd Berlin Conference on Asian Security (Berlin Group) Berlin, 4/5 October 2007 A conference jointly organised by Stiftung Wissenschaft und Politik (SWP), Berlin, and the Federal Ministry of Defence, Berlin Discussion Paper Do Note Cite or Quote without Author’s Permission Stiftung Wissenschaft und Politik CHINESE COMMUNIST PARTY STRATEGIES FOR CONTAINING SOCIAL PROTEST1 Murray Scott Tanner German Institute for International and Security Affairs 1 After most of the research on this project was completed, the author joined the U.S. Congressional Executive Commission on China. All of the views contained in this article are solely those of the author, and do not necessarily represent those of the CECC, its Commissioners, or staff. The present draft is not for citation, quotation or further attribution without the authors’s permission. SWP Ludwigkirchplatz 3–4 10719 Berlin Phone +49 30 880 07-0 Fax +49 30 880 07-100 www.swp-berlin.org MAJOR ELEMENTS OF THE CCP’S SOCIAL STABILITY STRATEGY During CCP General Secretary Hu Jintao first term, the CCP leadership has developed a multi-pronged long-term strategy aimed at confronting and containing China’s high levels of social protest and reinforcing the Party’s power over society. The Hu leadership’s strategy is based on the thesis that China’s decade-long increases in social disorder reflect China’s passage into a critical transitional stage of development that the CCP must carefully navigate if it is to survive in power. In his February 2005 major address on forging an “harmonious socialist society,”