Fifth Southeast Enzyme Conference Saturday, April 5, 2014

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Electromicrobial Transformations Using the Pyruvate Synthase System of Clostridium Sporogenes

I I I 1 Bioelec~rochemistryand Bioenergetics, 21 (1989) 245-259 A section of J. Electroanal. Cheni., and constituting Vol. 275 (1989) Elsevier Sequoia S.A.. Lausanne - Printed in The Netherlands b ' I L Electromicrobial transformations using the pyruvate synthase system of Clostridium sporogenes Neil M. Dixon, Eurig W. James, Robert W. Lovitt * and Douglas B. Kell Departmen1 o/ Biological Sciences, University College of IVules, Aberystwylh, Djfed SY23 3DA (Great Britain) (Received 3 December 1988; in revised form 17 January 1989) I I J A bioelectrochemical method by which the enzymology of reductive carboxylations (RCOOH +C02 +6 [H]+RCH2COOH+2 H,O) could be investigated is described. This method was used for a I detailed study of the enynnology of the overall reaction (viz. acetyl phosphate to pyruvate) catalysed by I pyruvate synthase in Clostridium sporogenes. The same method could be utilised to harness such reductive I carboxylations for commercial biotransformations of xenobiotics. By adjusting the reaction conditions it was possible to alter the proportions of the products synthesised, and to synthesise compounds more reduced and/or with a greater number of carbon atoms than pyruvate. INTRODUCTION ! The proteolytic clostridia have been the subject of renewed interest, with the attention being focussed upon biotechnologically useful enyzmes that these I organisms produce. Apart from extracellular hydrolases, most notable are enoate [I-41, nitroaryl [5],linoleate [6],2-oxoacid [7], proline [8] and glycine reductases [9]. Recent investigations in this laboratory have concentrated upon Clostridiunz sporo- 1 genes[lO-171. Dixon [I71 detailed the effects of CO, on both the inhibition/stimulation and induction/repression of some of the "capnic" enzymes of CI. -

1 Studies on 3-Hydroxypropionate Metabolism in Rhodobacter

Studies on 3-Hydroxypropionate Metabolism in Rhodobacter sphaeroides Dissertation Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University By Steven Joseph Carlson Graduate Program in Microbiology The Ohio State University 2018 Dissertation Committee Dr. Birgit E. Alber, Advisor Dr. F. Robert Tabita Dr. Venkat Gopalan Dr. Joseph A. Krzycki 1 Copyrighted by Steven Joseph Carlson 2018 2 Abstract In this work, the involvement of multiple biochemical pathways used by the metabolically versatile Rhodobacter sphaeroides to assimilate 3-hydroxypropionate was investigated. In Chapter 2, evidence of a 3-hydroxypropionate oxidative path is presented. The mutant RspdhAa2SJC was isolated which lacks pyruvate dehydrogenase activity and is unable to grow with pyruvate. Robust 3-hydropropionate growth with RspdhAa2SJC indicated an alternative mechanism exists to maintain the acetyl-CoA pool. Further, RsdddCMA4, lacking the gene encoding a possible malonate semialdehyde dehydrogenase, was inhibited for growth with 3-hydroxypropionate providing support for a 3-hydroxypropionate oxidative pathway which involves conversion of malonate semialdehyde to acetyl-CoA. We propose that the 3- hydroxypropionate growth of RspdhAa2SJC is due to the oxidative conversion of 3- hydroxypropionate to acetyl-CoA. In Chapter 3, the involvement of the ethylmalonyl-CoA pathway (EMCP) during growth with 3-hydroxypropionate was studied. Phenotypic analysis of mutants of the EMCP resulted in varying degrees of 3-hydroxypropionate growth. Specifically, a mutant lacking crotonyl-CoA carboxylase/reductase grew similar to wild type with 3- hydroxypropionate. However, mutants lacking subsequent enzymes in the EMCP exhibited 3-hydroxypropionate growth defects that became progressively more severe the ii later the enzyme participated in the EMCP. -

Supplement 1 Overview of Dystonia Genes

Supplement 1 Overview of genes that may cause dystonia in children and adolescents Gene (OMIM) Disease name/phenotype Mode of inheritance 1: (Formerly called) Primary dystonias (DYTs): TOR1A (605204) DYT1: Early-onset generalized AD primary torsion dystonia (PTD) TUBB4A (602662) DYT4: Whispering dystonia AD GCH1 (600225) DYT5: GTP-cyclohydrolase 1 AD deficiency THAP1 (609520) DYT6: Adolescent onset torsion AD dystonia, mixed type PNKD/MR1 (609023) DYT8: Paroxysmal non- AD kinesigenic dyskinesia SLC2A1 (138140) DYT9/18: Paroxysmal choreoathetosis with episodic AD ataxia and spasticity/GLUT1 deficiency syndrome-1 PRRT2 (614386) DYT10: Paroxysmal kinesigenic AD dyskinesia SGCE (604149) DYT11: Myoclonus-dystonia AD ATP1A3 (182350) DYT12: Rapid-onset dystonia AD parkinsonism PRKRA (603424) DYT16: Young-onset dystonia AR parkinsonism ANO3 (610110) DYT24: Primary focal dystonia AD GNAL (139312) DYT25: Primary torsion dystonia AD 2: Inborn errors of metabolism: GCDH (608801) Glutaric aciduria type 1 AR PCCA (232000) Propionic aciduria AR PCCB (232050) Propionic aciduria AR MUT (609058) Methylmalonic aciduria AR MMAA (607481) Cobalamin A deficiency AR MMAB (607568) Cobalamin B deficiency AR MMACHC (609831) Cobalamin C deficiency AR C2orf25 (611935) Cobalamin D deficiency AR MTRR (602568) Cobalamin E deficiency AR LMBRD1 (612625) Cobalamin F deficiency AR MTR (156570) Cobalamin G deficiency AR CBS (613381) Homocysteinuria AR PCBD (126090) Hyperphelaninemia variant D AR TH (191290) Tyrosine hydroxylase deficiency AR SPR (182125) Sepiaterine reductase -

1 Silencing Branched-Chain Ketoacid Dehydrogenase Or

bioRxiv preprint doi: https://doi.org/10.1101/2020.02.21.960153; this version posted February 22, 2020. The copyright holder for this preprint (which was not certified by peer review) is the author/funder, who has granted bioRxiv a license to display the preprint in perpetuity. It is made available under aCC-BY-NC-ND 4.0 International license. Silencing branched-chain ketoacid dehydrogenase or treatment with branched-chain ketoacids ex vivo inhibits muscle insulin signaling Running title: BCKAs impair insulin signaling Dipsikha Biswas1, PhD, Khoi T. Dao1, BSc, Angella Mercer1, BSc, Andrew Cowie1 , BSc, Luke Duffley1, BSc, Yassine El Hiani2, PhD, Petra C. Kienesberger1, PhD, Thomas Pulinilkunnil1†, PhD 1Department of Biochemistry and Molecular Biology, Dalhousie Medicine New Brunswick, Saint John, New Brunswick, Canada, 2Department of Physiology and Biophysics, Dalhousie University, Halifax, Nova Scotia, Canada. †Correspondence to Thomas Pulinilkunnil, PhD Department of Biochemistry and Molecular Biology, Faculty of Medicine, Dalhousie University Dalhousie Medicine New Brunswick, 100 Tucker Park Road, Saint John E2L4L5, New Brunswick, Canada. Telephone: (506) 636-6973; Fax: (506) 636-6001; email: [email protected]. 1 bioRxiv preprint doi: https://doi.org/10.1101/2020.02.21.960153; this version posted February 22, 2020. The copyright holder for this preprint (which was not certified by peer review) is the author/funder, who has granted bioRxiv a license to display the preprint in perpetuity. It is made available under aCC-BY-NC-ND 4.0 International -

SUPPY Liglucosexlmtdh

US 20100314248A1 (19) United States (12) Patent Application Publication (10) Pub. No.: US 2010/0314248 A1 Worden et al. (43) Pub. Date: Dec. 16, 2010 (54) RENEWABLE BOELECTRONIC INTERFACE Publication Classification FOR ELECTROBOCATALYTC REACTOR (51) Int. Cl. (76) Inventors: Robert M. Worden, Holt, MI (US); C25B II/06 (2006.01) Brian L. Hassler, Lake Orion, MI C25B II/2 (2006.01) (US); Lawrence T. Drzal, Okemos, GOIN 27/327 (2006.01) MI (US); Ilsoon Lee, Okemo s, MI BSD L/04 (2006.01) (US) C25B 9/00 (2006.01) (52) U.S. Cl. ............... 204/403.14; 204/290.11; 204/400; Correspondence Address: 204/290.07; 427/458; 204/252: 977/734; PRICE HENEVELD COOPER DEWITT & LIT 977/742 TON, LLP 695 KENMOOR, S.E., PO BOX 2567 (57) ABSTRACT GRAND RAPIDS, MI 495.01 (US) An inexpensive, easily renewable bioelectronic device useful for bioreactors, biosensors, and biofuel cells includes an elec (21) Appl. No.: 12/766,169 trically conductive carbon electrode and a bioelectronic inter face bonded to a surface of the electrically conductive carbon (22) Filed: Apr. 23, 2010 electrode, wherein the bioelectronic interface includes cata lytically active material that is electrostatically bound directly Related U.S. Application Data or indirectly to the electrically conductive carbon electrode to (60) Provisional application No. 61/172,337, filed on Apr. facilitate easy removal upon a change in pH, thereby allowing 24, 2009. easy regeneration of the bioelectronic interface. 7\ POWER 1 - SUPPY|- LIGLUCOSEXLMtDH?till pi 6.0 - esses&aaaas-exx-xx-xx-xx-xxxxixax-e- Patent Application Publication Dec. 16, 2010 Sheet 1 of 18 US 2010/0314248 A1 Potential (nV) Patent Application Publication Dec. -

Catabolic and Anabolic Enzyme Activities and Energetics of Acetone Metabolism of the Sulfate-Reducing Bacterium Desulfococcus Biacutus

JOURNAL OF BACTERIOLOGY, Jan. 1995, p. 277–282 Vol. 177, No. 2 0021-9193/95/$04.0010 Copyright q 1995, American Society for Microbiology Catabolic and Anabolic Enzyme Activities and Energetics of Acetone Metabolism of the Sulfate-Reducing Bacterium Desulfococcus biacutus PETER H. JANSSEN* AND BERNHARD SCHINK Fakulta¨t fu¨r Biologie, Universita¨t Konstanz, D-78434 Konstanz, Germany Received 1 August 1994/Accepted 7 November 1994 Acetone degradation by cell suspensions of Desulfococcus biacutus was CO2 dependent, indicating initiation by a carboxylation reaction, while degradation of 3-hydroxybutyrate was not CO2 dependent. Growth on 3-hydroxybutyrate resulted in acetate accumulation in the medium at a ratio of 1 mol of acetate per mol of substrate degraded. In acetone-grown cultures no coenzyme A (CoA) transferase or CoA ligase appeared to be involved in acetone metabolism, and no acetate accumulated in the medium, suggesting that the carboxylation of acetone and activation to acetoacetyl-CoA may occur without the formation of a free intermediate. Catab- olism of 3-hydroxybutyrate occurred after activation by CoA transfer from acetyl-CoA, followed by oxidation to acetoacetyl-CoA. In both acetone-grown cells and 3-hydroxybutyrate-grown cells, acetoacetyl-CoA was thiolyti- Downloaded from cally cleaved to two acetyl-CoA residues and further metabolized through the carbon monoxide dehydrogenase pathway. Comparison of the growth yields on acetone and 3-hydroxybutyrate suggested an additional energy requirement in the catabolism of acetone. This is postulated to be the carboxylation reaction (DG&* for the carboxylation of acetone to acetoacetate, 117.1 kJ z mol21). At the intracellular acyl-CoA concentrations measured, the net free energy change of acetone carboxylation and catabolism to two acetyl-CoA residues would be close to 0 kJ z mol of acetone21, if one mol of ATP was invested. -

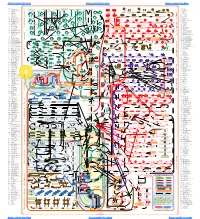

Generated by SRI International Pathway Tools Version 25.0, Authors S

Authors: Pallavi Subhraveti Peter D Karp Ingrid Keseler An online version of this diagram is available at BioCyc.org. Biosynthetic pathways are positioned in the left of the cytoplasm, degradative pathways on the right, and reactions not assigned to any pathway are in the far right of the cytoplasm. Transporters and membrane proteins are shown on the membrane. Anamika Kothari Periplasmic (where appropriate) and extracellular reactions and proteins may also be shown. Pathways are colored according to their cellular function. Gcf_000789375Cyc: Thermotoga sp. Cell2 Cellular Overview Connections between pathways are omitted for legibility. -

Dynamic Control Over Feedback Regulation Identifies Pyruvate-Ferredoxin Oxidoreductase As a Central Metabolic Enzyme in Stationary Phase E

bioRxiv preprint doi: https://doi.org/10.1101/2020.07.26.219949; this version posted August 10, 2020. The copyright holder for this preprint (which was not certified by peer review) is the author/funder. All rights reserved. No reuse allowed without permission. Dynamic control over feedback regulation identifies pyruvate-ferredoxin oxidoreductase as a central metabolic enzyme in stationary phase E. coli. 1,* 2,* 2 2 2,3, + Shuai Li , Zhixia Ye , Juliana Lebeau , Eirik A. Moreb ,and Michael D. Lynch 1 Department of Chemistry, Duke University 2 Department of Biomedical Engineering, Duke University *Authors contributed equally to this work. 3 To whom all correspondence should be addressed. [email protected] Abstract: We demonstrate the use of two-stage dynamic metabolic control to manipulate feedback regulation in central metabolism and improve stationary phase biosynthesis in engineered E. coli. Specifically, we report the impact of dynamic control over two enzymes: citrate synthase, and glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase, on stationary phase fluxes. Firstly, reduced citrate synthase levels lead to a reduction in 휶-ketoglutarate, which is an inhibitor of sugar transport, resulting in increased stationary phase glucose uptake and glycolytic fluxes. Reduced glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase activity activates the SoxRS regulon and expression of pyruvate-ferredoxin oxidoreductase, which is in turn responsible for large increases in acetyl-CoA production. The combined reduction in citrate synthase and glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase, leads to greatly enhanced stationary phase metabolism and the improved production of citramalic acid enabling titers of 126±7g/L. These results identify pyruvate oxidation via the pyruvate-ferredoxin oxidoreductase as a “central” metabolic pathway in stationary phase E. -

Index of Recommended Enzyme Names

Index of Recommended Enzyme Names EC-No. Recommended Name Page 1.2.1.10 acetaldehyde dehydrogenase (acetylating) 115 1.2.1.38 N-acetyl-y-glutamyl-phosphate reductase 289 1.2.1.3 aldehyde dehydrogenase (NAD+) 32 1.2.1.4 aldehyde dehydrogenase (NADP+) 63 1.2.99.3 aldehyde dehydrogenase (pyrroloquinoline-quinone) 578 1.2.1.5 aldehyde dehydrogenase [NAD(P)+] 72 1.2.3.1 aldehyde oxidase 425 1.2.1.31 L-aminoadipate-semialdehyde dehydrogenase 262 1.2.1.19 aminobutyraldehyde dehydrogenase 195 1.2.1.32 aminomuconate-semialdehyde dehydrogenase 271 1.2.1.29 aryl-aldehyde dehydrogenase 255 1.2.1.30 aryl-aldehyde dehydrogenase (NADP+) 257 1.2.3.9 aryl-aldehyde oxidase 471 1.2.1.11 aspartate-semialdehyde dehydrogenase 125 1.2.1.6 benzaldehyde dehydrogenase (deleted) 88 1.2.1.28 benzaldehyde dehydrogenase (NAD+) 246 1.2.1.7 benzaldehyde dehydrogenase (NADP+) 89 1.2.1.8 betaine-aldehyde dehydrogenase 94 1.2.1.57 butanal dehydrogenase 372 1.2.99.2 carbon-monoxide dehydrogenase 564 1.2.3.10 carbon-monoxide oxidase 475 1.2.2.4 carbon-monoxide oxygenase (cytochrome b-561) 422 1.2.1.45 4-carboxy-2-hydroxymuconate-6-semialdehyde dehydrogenase .... 323 1.2.99.6 carboxylate reductase 598 1.2.1.60 5-carboxymethyl-2-hydroxymuconic-semialdehyde dehydrogenase . 383 1.2.1.44 cinnamoyl-CoA reductase 316 1.2.1.68 coniferyl-aldehyde dehydrogenase 405 1.2.1.33 (R)-dehydropantoate dehydrogenase 278 1.2.1.26 2,5-dioxovalerate dehydrogenase 239 1.2.1.69 fluoroacetaldehyde dehydrogenase 408 1.2.1.46 formaldehyde dehydrogenase 328 1.2.1.1 formaldehyde dehydrogenase (glutathione) -

Investigation of the Anabolic Pyruvate Oxidoreductase And

INVESTIGATION OF THE ANABOLIC PYRUVATE OXIDOREDUCTASE AND THE FUNCTION OF POREF IN METHANOCOCCUS MARIPALUDIS by WINSTON CHI-KUANG LIN (under the direction of WILLIAM B. WHITMAN) ABSTRACT The pyruvate oxidoreductase (POR) catalyzes the reversible oxidation of pyruvate. For hydrogenotrophic methanogens, the anabolic POR catalyses the energetically unfavorable reductive carboxylation of acetyl-CoA to form pyruvate, a precursor of organic carbon synthesized in methanogens. Previously, the methanoccocal POR was purified to homogeneity. It contained five polypeptides, four of which were found to be similar to the four subunit (a, b, d, and g) POR. For further characterization, the por gene cluster was isolated and sequenced. Six open reading frames were found, porABCDEF. The gene porE encoded the fifth subunit that copurified with the POR. Also identified was porF, which was similar to porE. Both porE and porF contained high cysteinyl residue content and two Fe/S binding motifs, suggesting that porE and porF may serve as electron carriers for the methanococcal POR. To further elucidate the role of PorE and PorF, a deletional mutant strain JJ150 was constructed which lacked porEF. Growth of the mutant in minimal McN medium was slower than the growth of the wild type strain JJ1. POR, hydrogenase, and carbon monoxide dehydrogenase activities in JJ150 were similar to the wild type. In contrast, pyruvate-dependent methanogenesis was inhibited in JJ150. Complementation of the mutant with porEF restored growth and pyruvate-dependent methanogenesis to wild type levels. Partial complementation of porE or porF yielded different results. Partial complementation with porE restored methanogenesis but not growth. Complementation with porF did not restore methanogenesis but did partially restore growth. -

O O2 Enzymes Available from Sigma Enzymes Available from Sigma

COO 2.7.1.15 Ribokinase OXIDOREDUCTASES CONH2 COO 2.7.1.16 Ribulokinase 1.1.1.1 Alcohol dehydrogenase BLOOD GROUP + O O + O O 1.1.1.3 Homoserine dehydrogenase HYALURONIC ACID DERMATAN ALGINATES O-ANTIGENS STARCH GLYCOGEN CH COO N COO 2.7.1.17 Xylulokinase P GLYCOPROTEINS SUBSTANCES 2 OH N + COO 1.1.1.8 Glycerol-3-phosphate dehydrogenase Ribose -O - P - O - P - O- Adenosine(P) Ribose - O - P - O - P - O -Adenosine NICOTINATE 2.7.1.19 Phosphoribulokinase GANGLIOSIDES PEPTIDO- CH OH CH OH N 1 + COO 1.1.1.9 D-Xylulose reductase 2 2 NH .2.1 2.7.1.24 Dephospho-CoA kinase O CHITIN CHONDROITIN PECTIN INULIN CELLULOSE O O NH O O O O Ribose- P 2.4 N N RP 1.1.1.10 l-Xylulose reductase MUCINS GLYCAN 6.3.5.1 2.7.7.18 2.7.1.25 Adenylylsulfate kinase CH2OH HO Indoleacetate Indoxyl + 1.1.1.14 l-Iditol dehydrogenase L O O O Desamino-NAD Nicotinate- Quinolinate- A 2.7.1.28 Triokinase O O 1.1.1.132 HO (Auxin) NAD(P) 6.3.1.5 2.4.2.19 1.1.1.19 Glucuronate reductase CHOH - 2.4.1.68 CH3 OH OH OH nucleotide 2.7.1.30 Glycerol kinase Y - COO nucleotide 2.7.1.31 Glycerate kinase 1.1.1.21 Aldehyde reductase AcNH CHOH COO 6.3.2.7-10 2.4.1.69 O 1.2.3.7 2.4.2.19 R OPPT OH OH + 1.1.1.22 UDPglucose dehydrogenase 2.4.99.7 HO O OPPU HO 2.7.1.32 Choline kinase S CH2OH 6.3.2.13 OH OPPU CH HO CH2CH(NH3)COO HO CH CH NH HO CH2CH2NHCOCH3 CH O CH CH NHCOCH COO 1.1.1.23 Histidinol dehydrogenase OPC 2.4.1.17 3 2.4.1.29 CH CHO 2 2 2 3 2 2 3 O 2.7.1.33 Pantothenate kinase CH3CH NHAC OH OH OH LACTOSE 2 COO 1.1.1.25 Shikimate dehydrogenase A HO HO OPPG CH OH 2.7.1.34 Pantetheine kinase UDP- TDP-Rhamnose 2 NH NH NH NH N M 2.7.1.36 Mevalonate kinase 1.1.1.27 Lactate dehydrogenase HO COO- GDP- 2.4.1.21 O NH NH 4.1.1.28 2.3.1.5 2.1.1.4 1.1.1.29 Glycerate dehydrogenase C UDP-N-Ac-Muramate Iduronate OH 2.4.1.1 2.4.1.11 HO 5-Hydroxy- 5-Hydroxytryptamine N-Acetyl-serotonin N-Acetyl-5-O-methyl-serotonin Quinolinate 2.7.1.39 Homoserine kinase Mannuronate CH3 etc. -

Meta-Proteomics of Rumen Microbiota Indicates Niche

www.nature.com/scientificreports OPEN Meta-proteomics of rumen microbiota indicates niche compartmentalisation and Received: 7 June 2017 Accepted: 29 June 2018 functional dominance in a limited Published: xx xx xxxx number of metabolic pathways between abundant bacteria E. H. Hart, C. J. Creevey , T. Hitch & A. H. Kingston-Smith The rumen is a complex ecosystem. It is the primary site for microbial fermentation of ingested feed allowing conversion of a low nutritional feed source into high quality meat and milk products. However, digestive inefciencies lead to production of high amounts of environmental pollutants; methane and nitrogenous waste. These inefciencies could be overcome by development of forages which better match the requirements of the rumen microbial population. Although challenging, the application of meta-proteomics has potential for a more complete understanding of the rumen ecosystem than sequencing approaches alone. Here, we have implemented a meta-proteomic approach to determine the association between taxonomies of microbial sources of the most abundant proteins in the rumens of forage-fed dairy cows, with taxonomic abundances typical of those previously described by metagenomics. Reproducible proteome profles were generated from rumen samples. The most highly abundant taxonomic phyla in the proteome were Bacteriodetes, Firmicutes and Proteobacteria, which corresponded with the most abundant taxonomic phyla determined from 16S rRNA studies. Meta- proteome data indicated diferentiation between metabolic pathways of the most abundant phyla, which is in agreement with the concept of diversifed niches within the rumen microbiota. Te rumen plays host to a complex microbiome consisting of over seven thousand species from protozoa, archaea, bacteria and fungi and is the primary site for microbial fermentation of ingested feed in ruminants1.