Regenerating the Human Right to a Clean and Healthy Environment in the Commons Renaissance

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

JAMES CUMMINS Bookseller Catalogue 121 James Cummins Bookseller Catalogue 121 to Place Your Order, Call, Write, E-Mail Or Fax

JAMES CUMMINS bookseller catalogue 121 james cummins bookseller catalogue 121 To place your order, call, write, e-mail or fax: james cummins bookseller 699 Madison Avenue, New York City, 10065 Telephone (212) 688-6441 Fax (212) 688-6192 e-mail: [email protected] jamescumminsbookseller.com hours: Monday – Friday 10:00 – 6:00, Saturday 10:00 – 5:00 Members A.B.A.A., I.L.A.B. front cover: item 20 inside front cover: item 12 inside rear cover: item 8 rear cover: item 19 catalogue photography by nicole neenan terms of payment: All items, as usual, are guaranteed as described and are returnable within 10 days for any reason. All books are shipped UPS (please provide a street address) unless otherwise requested. Overseas orders should specify a shipping preference. All postage is extra. New clients are requested to send remittance with orders. Libraries may apply for deferred billing. All New York and New Jersey residents must add the appropriate sales tax. We accept American Express, Master Card, and Visa. 1 ALBIN, Eleazar. A Natural History of English Insects Illustrated with a Hundred Copper Plates, Curiously Engraven from the Life: And (for those whose desire it) Exactly Coloured by the Author [With:] [Large Notes, and many Curious Observations. By W. Derham]. With 100 hand-colored engraved plates, each accompanied by a letterpress description. [2, title page dated 1720 (verso blank)], [2, dedica- tion by Albin], [4, preface], [4, list of subscribers], [2, title page dated 1724 (verso blank)], [2, dedication by Derham; To the Reader (on verso)], 26, [2, Index], [100] pp. -

Global Environmental Policy with a Case Study of Brazil

ENVS 360 Global Environmental Policy with a Case Study of Brazil Professor Pete Lavigne, Environmental Studies and Director of the Colorado Water Workshop Taylor Hall 312c Office Hours T–Friday 11:00–Noon or by appointment 970-943-3162 – Mobile 503-781-9785 Course Policies and Syllabus ENVS 360 Global Environmental Policy. This multi-media and discussion seminar critically examines key perspectives, economic and political processes, policy actors, and institutions involved in global environmental issues. Students analyze ecological, cultural, and social dimensions of international environmental concerns and governance as they have emerged in response to increased recognition of global environmental threats, globalization, and international contributions to understanding of these issues. The focus of the course is for students to engage and evaluate texts within the broad policy discourse of globalization, justice and the environment. Threats to Earth's environment have increasingly become globalized and in response to at least ten major global threats—including global warming, deforestation, population growth and persistent organic pollutants—countries, NGOs and corporations have signed hundreds of treaties, conventions and various other types of agreements designed to protect or at least mitigate and minimize damage to the environment. The course provides an overview of developments and patterns in the epistemological, political, social and economic dimensions of global environmental governance as they have emerged over the past three decades. We will also undertake a case study of the interactions of Brazilian environmental policy central to several global environmental threats, including global warming and climate change, land degradation, and freshwater pollution and scarcity. The case study will analyze the intersections of major local, national and international environmental policies. -

Subhankar Banerjee Resume

SUBHANKAR BANERJEE I was born in 1967 in Berhampore, a small town near Kolkata, India. My early experiences in my tropical home in rural Bengal fostered my life long interest in the value of land and it’s resources. In the cinemas of these small towns, I came to know the work of brilliant Bengali filmmakers including, Satyajit Ray, Mrinal Sen, and Ritwik Ghatak. I loved cinema and found their visual explorations of everyday life and larger social issues immensely inspiring. I asked my Great Uncle Bimal Mookerjee, a painter, to teach me how to paint. I created portraits and detailed rural scenes, but knew from growing up in a middle-income family that it would be nearly impossible for me to pursue a career in the arts. I chose instead the practical path of studying engineering in India and later earned master’s degrees in physics and computer science at New Mexico State University. In the New Mexican Desert, I fell in love with the open spaces of the American West. I hiked and backpacked frequently in New Mexico, Arizona, Colorado, and Utah, and bought a 35mm camera with which I began taking photographs. After finishing my graduate degrees in Physics and Computer Science, I moved to Seattle, Washington to take up a research job in the sciences. In the Pacific Northwest, my commitment to photography grew, and I photographed extensively during many outdoor trips in Washington, Oregon, Montana, Wyoming, California, New Hampshire, Vermont, Florida, British Columbia, Alberta, and Manitoba. In 2000, I decided to leave my scientific career behind and began a large-scale photography project in the American Arctic. -

This Is the Bennington Museum Library's “History-Biography” File, with Information of Regional Relevance Accumulated O

This is the Bennington Museum library’s “history-biography” file, with information of regional relevance accumulated over many years. Descriptions here attempt to summarize the contents of each file. The library also has two other large files of family research and of sixty years of genealogical correspondence, which are not yet available online. Abenaki Nation. Missisquoi fishing rights in Vermont; State of Vermont vs Harold St. Francis, et al.; “The Abenakis: Aborigines of Vermont, Part II” (top page only) by Stephen Laurent. Abercrombie Expedition. General James Abercrombie; French and Indian Wars; Fort Ticonderoga. “The Abercrombie Expedition” by Russell Bellico Adirondack Life, Vol. XIV, No. 4, July-August 1983. Academies. Reproduction of subscription form Bennington, Vermont (April 5, 1773) to build a school house by September 20, and committee to supervise the construction north of the Meeting House to consist of three men including Ebenezer Wood and Elijah Dewey; “An 18th century schoolhouse,” by Ruth Levin, Bennington Banner (May 27, 1981), cites and reproduces April 5, 1773 school house subscription form; “Bennington's early academies,” by Joseph Parks, Bennington Banner (May 10, 1975); “Just Pokin' Around,” by Agnes Rockwood, Bennington Banner (June 15, 1973), re: history of Bennington Graded School Building (1914), between Park and School Streets; “Yankee article features Ben Thompson, MAU designer,” Bennington Banner (December 13, 1976); “The fall term of Bennington Academy will commence (duration of term and tuition) . ,” Vermont Gazette, (September 16, 1834); “Miss Boll of Massachusetts, has opened a boarding school . ,” Bennington Newsletter (August 5, 1812; “Mrs. Holland has opened a boarding school in Bennington . .,” Green Mountain Farmer (January 11, 1811); “Mr. -

Promoting Political Rights to Protect the Environment

Promoting Political Rights to Protect the Environment Michael J. Kanel I. INTRODUCTION ................................................ 389 1I. POLITICAL RIGHTS AFFECTING ENVIRONMENTAL PROTECTION ................... 391 A. The Right to Freedom of Expression and PoliticalParticipation ............... 391 1. Indigenous Communities .................................... 391 2. IndividualActivists ......................................... 393 B. The Right to Know of EnvironmentalHazards .......................... 396 1. The Soviet Union .......................................... 396 2. The United States ......................................... 398 M. INSTrrUTIONS, POLICmS, AND PROGRAMS ............................... 399 A. The United Nations .......................................... 399 1. U.N. Bodies ............................................ 400 2. The InternationalLabor Organization............................. 401 3. U.N.-Sponsored Conferences ................................. 401 4. Recommendations ......................................... 403 B. Organizationof American States .................................. 404 C. Organization of African Unity ..................................... 405 D. Organizationfor Economic Cooperation and Development .................. 406 E. Group of Seven ............................................. 407 F. MultilateralDevelopment Banks .................................. 407 G. The United States ............................................ 410 IV. CONCLUSION ............................................... -

Young Alumni Embrace Tech Industry Catching up with George Carlisle

Alumni Horae ST. PAUL’S SCHOOL WINTER 2016 Young alumni embrace tech industry Catching up with George Carlisle Milkey ’74 reflects on landmark case SCHOOLHOUSE READING ROOM / PHOTO: PERRY SMITH 1 RECTOR Adapting for the Future As we began our It turns out my fears about the impact of such budgeting process a primitive technology as landline telephones PETER FINGER earlier this winter, were overblown, at least temporarily. Students our IT director sug- and teachers still communicated face-to-face, gested we discontinue still smiled at one another in person – they still technical support for do. But thinking back to those earlier concerns, it hard-wired phones seems FAT’s notion about the risks of technology in all student rooms. may not have been completely out of place. These He explained that our risks were recently summarized in the title of MIT students no longer sociologist Sherry Turkle’s book Alone Together: use landline phones. Why We Expect More from Technology and Less I was assured that discontinuing this service from Each Other. would not compromise the safety of our students, The complex issue of how technology is chang- who would still have landline access, if they ever ing relationships is very much on our minds at needed it, in their house common rooms. So, the School. In June, Dr. Turkle and other scholars landline phones died quietly in a budget meeting. and school leaders from around the country will I remember the introduction of phones in stu- join us for a St. Paul’s School symposium entitled dent rooms 20 years ago. -

This Is the Bennington Museum Library's “History-Biography” File, With

This is the Bennington Museum library’s “history-biography” file, with information of regional relevance accumulated over many years. Descriptions here attempt to summarize the contents of each file. The library also has two other large files of family research and of sixty years of genealogical correspondence, which are not yet available online. Abenaki Nation. Missisquoi fishing rights in Vermont; State of Vermont vs Harold St. Francis, et al.; “The Abenakis: Aborigines of Vermont, Part II” (top page only) by Stephen Laurent. Abercrombie Expedition. General James Abercrombie; French and Indian Wars; Fort Ticonderoga. “The Abercrombie Expedition” by Russell Bellico Adirondack Life, Vol. XIV, No. 4, July-August 1983. Academies. Reproduction of subscription form Bennington, Vermont (April 5, 1773) to build a school house by September 20, and committee to supervise the construction north of the Meeting House to consist of three men including Ebenezer Wood and Elijah Dewey; “An 18th century schoolhouse,” by Ruth Levin, Bennington Banner (May 27, 1981), cites and reproduces April 5, 1773 school house subscription form; “Bennington's early academies,” by Joseph Parks, Bennington Banner (May 10, 1975); “Just Pokin' Around,” by Agnes Rockwood, Bennington Banner (June 15, 1973), re: history of Bennington Graded School Building (1914), between Park and School Streets; “Yankee article features Ben Thompson, MAU designer,” Bennington Banner (December 13, 1976); “The fall term of Bennington Academy will commence (duration of term and tuition) . ,” Vermont Gazette, (September 16, 1834); “Miss Boll of Massachusetts, has opened a boarding school . ,” Bennington Newsletter (August 5, 1812; “Mrs. Holland has opened a boarding school in Bennington . .,” Green Mountain Farmer (January 11, 1811); “Mr. -

Download This Issue: 05142014 Issue.Pdf

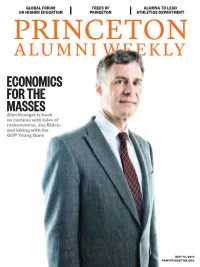

GLOBAL FORUM TREES OF ALUMNA TO LEAD ON HIGHER EDUCATION PRINCETON ATHLETICS DEPARTMENT PRINCETON ALUMNI WEEKLY ECONOMICS FOR THE MASSES Alan Krueger is back on campus with tales of rockonomics, Joe Biden, and biking with the GOP Young Guns MAY 14, 2014 PAW.PRINCETON.EDU 00paw0514_CovFinalSteve.indd 1 4/29/14 4:46 PM 140502_Deloitte.indd 1 2/26/14 3:25 PM 140502_Deloitte.indd 1 2/26/14 3:25 PM THANK YOU ALUMNI! W hen you remember your days at Princeton, was there someone who had a significant impact on your early career decisions? Someone who offered advice, who shared their insights, or advocated for you? Someone who helped shape your career direction? The Office of Career Services wishes to recognize the following alumni who partnered with our office and volunteered their time by participating in various student-alumni engagement programs and networking events this year. Now, more than ever, we appreciate the continued support of our dedicated alumni in helping students navigate the career decision-making process! Jamison O. Abbott ’96 S97 Leslie Conrad Dreibelbis ’77 S78 P07 P11 Frank N. Kotsen ’88 Kathryn E. Muessig ’02 David C. Schmidt ’02 Janet Y. Abrams *89 Janice K. Dru ’07 Ellen Kratzer ’84 Arka Mukherjee *95 Kurt A. Schoppe ’02 Mitchell A. Adler ’73 Lee L. Dudka *77 Alexandra N. Krupp ’10 Kunal G. Nayyar ’11 Stephen R. Schragger ’61 P93 Thomas S. Arias ’08 William H. Dwight ’84 S84 Allison L. Kuncik ’10 Paul B. Nehring ’10 S09 Bryton Ja-Shing Shang ’12 Michael Armstrong, Jr. ’85 S85 P14 P15 Kristin C. -

Proceedings of the Annual Meeting of the Association for Education in Journalism and Mass Communication (75Th, Montreal, Quebec, Canada, August 5-8, 1992). Part X: Health, Science

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 349 617 CS 507 964 TITLE Proceedings of the Annual Meeting of the Association for Education in Journalism and Mass Communication (75th, Montreal, Quebec, Canada, August 5-8, 1992). Part X: Health, Science, and the Environment. INSTITUTION Association for Education in Journalism and Mass Communication. PUB DATE Aug 92 NOTE 217p.; For other sections of these proceedings, see CS 507 955-970. For 1991 Proceedings, see ED 340 045. Some papers may contain light type. PUB TYPE Collected Works Conference Proceedings (021) Historical Materials (060) EDRS PRICE MF01/PC09 Plus Postage. DESCRIPTORS Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndrome; *Audience Response; Cognitive Processes; Communication Research; Foreign Countries; Media Research; *News Reporting; Programing (Broadcast); Risk; Science History; Sexuality; Space Exploration; Television IDENTIFIERS *Environmental Reporting; Health Communication; Print Media; Rhetorical Strategies; Science News; *Science Writing ABSTRACT The Health, Science, and the Environment section of these proceedings contains the following seven papers: "Columbus, Mars, and the Changing Images and Ideologies of Exploration: A Critical Examination" (Lin Bin and August T. Horvath); "Prime Time TV Portrayals of Sex, 'Safe Sex' and AIDS: A Longitudinal Analysis" (Dennis T. Lowry and Jon A. Shidler); "Reading Risk: Public Response to Print Media Accounts of Technological Risk" (Susanna Hornig and others); "Strategies of Evasion in Early 17th Century French Scientific Communication" (Jane Thornton Tolbert); "Words and Pictures: Expert and Lay Rationality in Television News" (Lee Wilkins); "News from the Rain Forest: The Social Integration of Environmental Journalism" (Allen Palmer); and "The Science Newswriting Process: A Study of Science Writers' Cognitive Processing of Information" (Jocelyn Steinke). (SR) *********************************************************************** AepioaucLIons suppiiea by taktb are tne best that can be made x * from the original document. -

Los Angeles Lawyer Magazine June 2018

LAWYER TO LAWYER THE MAGAZINE OF THE LOS ANGELES COUNTY BAR ASSOCIATION REFERRAL GUIDE2018 JUNE 2018 / $5 EARN MCLE CREDIT PLUS OPPOSITION RECOVERING TO SB 277 NAZI-LOOTED page 26 ART page 34 Indemnitor Liability page 14 Alimony Deduction Eliminated page 18 On Direct: Michael E. Meyer A Bridge page 10 to Justice Los Angeles Superior Court Judge Mark A. Juhas and attorney Maria E. Hall present a compelling case for the use of limited scope legal assistance page 20 FEATURES 20 A Bridge to Justice BY THE HONORABLE MARK A. JUHAS AND MARIA E. HALL Limited scope representation, or “unbundling,” offers a significant alternative for clients who require affordable legal assistance with partial or specific matters 26 Health First BY DENNIS F. HERNANDEZ The passage of SB 277 to eliminate the personal belief exemption for mandatory childhood vaccination raises serious issues about an individual’s right to liberty Plus: Earn MCLE credit. MCLE Test No. 279 appears on page 29. 34 Restoring Lost Legacies BY MARK I. LABATON Although legal hurdles remain, the Holocaust Expropriated Art Recovery Act of 2016 gives victims of Nazi plunder and their heirs a better opportunity to open the historical record and achieve a measure of justice 42 Special Section 2018 Lawyer-to-Lawyer Referral Guide Los Angeles Lawyer DEPARTME NTS the magazine of the Los Angeles County 8 LACBA Matters 18 Tax Tips Bar Association New study shows lawyers are America’s New federal law eliminates the alimony June 2018 loneliest professionals deduction BY STAN BISSEY BY PETER M. WALZER Volume 41, No. -

V·M·I University Microfilms International a Beil & Howell Information Company 300 ~~Orth Zeeb Road

The myth of the Amazon woman in Latin American literatures and cultures. Item Type text; Dissertation-Reproduction (electronic) Authors Dewey, Janice Laraine. Publisher The University of Arizona. Rights Copyright © is held by the author. Digital access to this material is made possible by the University Libraries, University of Arizona. Further transmission, reproduction or presentation (such as public display or performance) of protected items is prohibited except with permission of the author. Download date 07/10/2021 18:06:32 Link to Item http://hdl.handle.net/10150/185579 INFORMATION TO USERS This manuscript has been reproduced from the microfilm master. UMI films the text directly from the original or copy submitted. Thus, some thesis and dissertation copies are in typewriter face, while others may / be from any type of computer printer. The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. Broken or indistinct print, colored or poor quality illustrations and photographs, print bleedthrough, substandard margins, and improper alignment can adversely affect reproduction. In the unlikely event that the author did not send UMI a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if unauthorized copyright material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. Oversize materials (e.g., maps, drawings, charts) are reproduced by sectioning the original, beginning at the upper left-hand corner and continuing from left to right in equal sections with small overlaps. Each original is also photographed in one exposure and is included in reduced form at the back of the book. Photographs included in the original manuscript have been reproduced xerographically in this copy. -

CITIZENS of LONDON Lynne Olson

CITIZENS OF LONDON Lynne Olson NOTES INTRODUCTION xiii “convinced us”: Letter from unidentified sender, John Gilbert Winant scrap- book, in possession of Rivington Winant. xiv “We were”: Alex Danchev and Daniel Todman, eds., War Diaries, 1939–1945: Field Marshal Lord Alanbrooke (London: Weidenfeld & Nicolson, 2001), p. 248. “There were many”: John G. Winant, A Letter from Grosvenor Square: An Ac- count of a Stewardship (Boston: Houghton Mifflin, 1947), p. 3. “There was one man”: Times (London), April 24, 1946. “conveyed to the entire”: Wallace Carroll letter to Washington Post, undated, Winant papers, FDRL. xv “two prima donnas”: Robert E. Sherwood, Roosevelt and Hopkins: An Intimate History (New York: Harper and Brothers, 1948), p. 236. xvi “The British approached”: Carlo D’Este, Eisenhower: A Soldier’s Life (New York: Henry Holt, 2002), p. 337. xvii “It was not Mr. Winant”: “British Mourn Winant,” New York Times, Nov. 5, 1947. “Blacked out”: Donald L. Miller, Masters of the Air: America’s Bomber Boys Who Fought the Air War Against Nazi Germany (New York: Simon & Schuster, 2006), p. 137. xviii “This is an American- made”: Peter Clarke, The Last Thousand Days of the British Empire: Churchill, Roosevelt, and the Birth of the Pax Americana (New York: Bloomsbury, 2008), p. 103. “they needed to know”: Norman Longmate, The G.I.’s: The Americans in Brit- ain, 1942– 1945 (New York: Scribner, 1975), p. 376. “to concentrate on the things”: Star, Feb. 3, 1941. xix “must learn to live together”: Bernard Bellush, He Walked Alone: A Biography of John Gilbert Winant (The Hague: Mouton, 1968), p.