Commemorative Issue to Mark the Outbreak of World War

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

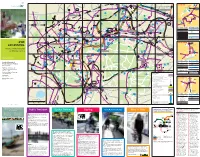

Bus Routes Running Every Day (Black Numbers)

Richmond Bus & Cycle M&G 26/01/2011 15:32 Page 1 2011 ABCDEFGH . E S E A to Heston Y A L Kew Bridge U O L OAD to W N I N N R KEW N Steam G O K BRENTFORD E RICHMOND R O L Ealing 267 V T G I A Museum BRIDGE E 391 Queen T N Y O U N A S A Orange Tree D R T Charlotte S A G S D O . E R 391 P U U O R T E Theatre D S C H R IN B O W H Hall/R.A.C.C. G 267 IS PAR H OAD R L W A . R L G 65 DE N A G K RO SYON LANE E IC T OLDHAW A Parkshot N E V R S GUNNERSBURY K CHISWICK D W O E D 267 T M D . N R E T Y 111 R O 65 BRIDGE ROAD BATH ROAD B P O . KEW K A H E PARK K GOLDHAWK ROAD W AT D T R D O H E M I W D H A W G R 267 E E H A L A A D LE G L R S H O R L 267 T R T D EY Little E I O O RE D R U HIGH ST ROAD N A Waterman’s R RO 391 TURNHAM L A H37.110 A D P B Green N A O S D Library R D Arts Centre G O GREEN D RICHMOND T H22 281 H37 OAD Kew Green W R E STAMFORD A G School K Richmond C U N STATION I ‘Bell’ Bus Station D DON 65 BROOK Richmond Q L A LON Green L R O B D E U N Theatre E 1 391 S CE A H RAVENSCOURT 1 E H D T E H to Hatton Cross and W LONDON D Main W A O R T HIGH STREET Thornbury A RS R R G S Kew Palace O Falcons PARK Heathrow Airport ISLEWORTH O Gate D O R O to F B Playing T R O D N E H37 A A ROAD H22 . -

ANNOUNCEMENTS by the MAYOR 1. on 5Th July 2012, I Was Delighted

ANNOUNCEMENTS BY THE MAYOR th 1. On 5 July 2012, I was delighted to attend Ealing Hammersmith & West London College, LLDD Awards Ceremony, Colet Gardens, W14 th 2. On 5 July, I attended the Standing Together event, Small Hall, HTH, W6 th 3. On 5 July, I was delighted to host and present with Cllr Greg Smith, HM The Queen’s (1952-2012) Diamond Jubilee Medals to members of staff from Parks Constabulary H&F, Mayor’s Parlour, HTH W6 th 4. On 5 July, accompanied by my consort, I attended The Regimental Cocktail Party, The Guards Museum, Wellington Barracks, Birdcage Walk SW1 th 5. On 6 July, I attended the Kumon Education Award Ceremony, W12 th 6. On 6 July, I attended the Mayor of Ealing’s Charity event, Ealing Town Hall, W5 th 7. On 7 July, accompanied by Cllr Frances Stainton, Deputy Mayor, I attended and officially opened ‘Fair on the Green’, Parsons Green, SW6 th 8. On 7 July, I attended All Saints School event, Bishops Park, SW6 th 9. On 7 July, I attended the National Childbirth Trust and Putney Branch Charity Fun Walk, FFC, SW6 th 10. On 7 July, I attended Addison Primary School event, W14 th 11. On 8 July, I attended the ‘Paggs Cup’ Football Tournament, South Park, SW6 th st 12. On 9 July, I attended the 21 Fulham Brownies charity cake sale in aid of Dementia UK, St Dionis Church Hall, St Dionis Road, SW6 th 13. On 9 July, I attended and spoke at the Business Awards, Basra Restaurant, W6 th 14. -

Members' Directory

ROYAL WARRANT HOLDERS ASSOCIATION MEMBERS’ DIRECTORY 2019–2020 SECRETARY’S FOREWORD 3 WELCOME Dear Reader, The Royal Warrant Holders Association represents one of the most diverse groups of companies in the world in terms of size and sector, from traditional craftspeople to global multinationals operating at the cutting edge of technology. The Members’ Directory lists companies by broad categories that further underline the range of skills, products and services that exist within the membership. Also included is a section dedicated to our principal charitable arm, the Queen Elizabeth Scholarship Trust (QEST), of which HRH The Prince of Wales is Patron. The section profiles the most recent alumni of scholars and apprentices to have benefited from funding, who have each developed their skills and promoted excellence in British craftsmanship. As ever, Royal Warrant holders and QEST are united in our dedication to service, quality and excellence as symbolised by the Royal Warrant of Appointment. We hope you find this printed directory of use when thinking of manufacturers and suppliers of products and services. An online version – which is regularly updated with company information and has enhanced search facilities – can be viewed on our website, www.royalwarrant.org “UNITED IN OUR DEDICATION TO Richard Peck SERVICE, QUALITY CEO & Secretary AND EXCELLENCE” The Royal Warrant Holders Association CONTENTS Directory of members Agriculture & Animal Welfare ...............................................................................................5 -

Healing Hidden Wounds

Veterans WORLD Issue 35 HEALING HIDDEN WOUNDS www.gov.uk/veterans-uk You can now find information about Veterans UK on GOV.UK. Whether you want information about how to apply for a medal, or need more urgent assistance as a veteran in a crisis, the Veterans UK webpages have information to help you. For further information please email [email protected] or call the Veterans UK Helpline on 0808 1914 2 18. July 2015 Veterans WORLD “However old you are, pick up the phone and get support. What’s the worst that could happen?” Update - Page 6 - Page 10 Dave Latimer 14 COntentS 4 News 6 The Armed Forces Covenant 8 Supporting, Enabling and Empowering 9 Pensions for Life 10 Healing Hidden Wounds 12 12 Driving Forward Employability for Veterans 14 Turn to Starboard to get back on track 16 RAF Veterans aided by new Advice Service 17 Pop-In for free advice 18 Welfare Staff out and about on Armed Forces Day 2015 The content of Veterans WORLD is provided to raise awareness of help, advice and support available to the 18 veterans community. Publication of articles on services Veterans World is distributed to those who work in an For information relating to War Pension/AFCS advisory role. claims please call the Veterans UK Helpline: provided or developments affecting To contact the Editor: 0808 1914 2 18. the veterans community does not Email: [email protected] mean that they are endorsed by For advertising opportunities please Email: Veterans WORLD or the Ministry of Want to make an editorial contribution? [email protected] Defence. -

FIND US Per Car Per Day Or £10 for Lunch Or Dinner Guests

BY ROA D From M25: leave at Junction 12 onto the M3, leading onto the (A316). Leave the (A316) at either the St Margaret’s Roundabout or Richmond Circus Roundabout. From St Margaret’s Roundabout (A316) – Follow St Margaret’s Road (A3004), past St Margaret’s Railway Station and continue to follow the road (A305) over Richmond Bridge. At mini- roundabout turn right onto the (A307) (signposted Kingston, Ham, Petersham). Follow Petersham Road (A307) for 300m before arrival. RICHMOND From Kew Road & Richmond Station (A307) – At Richmond Circus roundabout follow the signs for the (A307) (signposted Richmond). Continue past Richmond Station, turning left at traffic lights onto the one way system. Immediately move into the right-hand lane, turning right onto Eton Street and then again turning right onto Paradise Road. At T-junction turn left onto the (A307) (signposted Petersham, Kingston, Twickenham). At mini-roundabout continue onto the (A307) to Petersham Road for 300m before arrival. ST MARGARETS From Kingston & Ham – Follow the (A307) (signposted Richmond, Ham, Petersham). Continue past Ham Common and the Dysart Arms pub before turning left on the (A307) (signposted Richmond Town & Twickenham). Follow Petersham Road for 900m before arrival. BY T U B E Richmond upon Thames is served by the District Line. BY R A I L London Waterloo station can be reached directly in 20 EAST minutes allowing good connections to the city and TWICKENHAM 2 1 West End. The service also runs to Reading. BY B U S 3 The bus stop is immediately in front of Richmond Train Station. Number 65 heads towards Kingston, but get off at the 3rd stop (Compass Hill) in front of Richmond Brewery Stores. -

Richmond Upon Thames Lies 15 Miles Anniversary

www.visitrichmond.co.uk 2010 - 04 historic gems 2010 - 06 riverside retreat RICHMOND - 2010 08 breath of fresh air 2010 - 10 museums and galleries UPON 2010 - 12 eating out 2010 - 14 shopping 2010 - 16 history, ghosts and hauntings THAMES 2010 - 18 attractions 2010 - 26 map VisitRichmond Guide 2010 2010 - 30 richmond hill 2010 - 31 restaurants and bars 2010 - 36 accommodation 2010 - 46 venues 2010 - 50 travel information rrichmondichmond gguideuide 20102010 1 88/12/09/12/09 221:58:551:58:55 Full page advert ---- 2 - visitrichmond.co.uk rrichmondichmond gguideuide 20102010 2 88/12/09/12/09 221:59:221:59:22 Hampton Court Garden Welcome to Cllr Serge Lourie London’s Arcadia Richmond upon Thames lies 15 miles anniversary. The London Wetland Centre southwest of central London yet a fast in Barnes is an oasis of peace and a haven train form Waterloo Station will take you for wildlife close to the heart of the capital here in 15 minutes. When you arrive you while Twickenham Stadium the home of will emerge into a different world. England Rugby has a fantastic visitors centre which is open all year round. Defi ned by the Thames with over 16 miles of riverside we are without doubt the most I am extremely honoured to be Leader beautiful of the capitals 32 boroughs. It is of this beautiful borough. Our aim at the with good reason that we are known as Town Hall is to preserve and improve it for London’s Arcadia. everyone. Top of our agenda is protecting the environment and improving Richmond We really have something for everyone. -

October November 2018 Newsletter for Website

! ST ANDREW’S UNITED REFORMED CHURCH WALTON-ON-THAMES NEWSLETTER Volume 75 No 8 OCTOBER/NOVEMBER 2018 MINISTER CHURCH SECRETARY The Reverend Michael Hodgson Anna Crawford The Manse 23 Shaldon Way 3 Elgin Road Walton-on-Thames Weybridge KT12 3DJ KT13 8SN Tel: 01932 841382 Tel: 01932 244466 Email: [email protected] Email: [email protected] Website: www.standrewsurc.org © Te Royal Britsh Legion “We cherish, to, te Poppy red Tat grows on fields where valor led; It seems t signal t te skies Tat blood of heroes never dies…” Moina Michael From the Manse October 2018 I’d like to begin by thanking you for your kindness and care. As you know, both my parents have been very poorly this year but thankfully made remarkable recoveries from their earlier illnesses. In June we managed a family holiday in Sussex although during that week my sister and I realised that Dad was more frail than perhaps we’d realised. That being we had a wonderful week that we shall always look back on as being precious. Dad’s death came as a shock but two major heart attacks on consecutive days - well, it was obvious what was going to happen. I also think that there is some consolation in the knowledge that my father’s final illness wasn’t long and that if we think about what life was likely to hold for him had he lived, then the kindest thing for him is what did actually happen. The cards and messages and flowers we’ve received have been so very appreciated, a number containing all sorts of memories of him and his humour. -

Volunteering Events Calendar 2017 Richmond May Fair

Volunteering Events Calendar 2017 Richmond May Fair Richmond Green 13 May 2017, 10:00—18:00 The event Richmond May Fair is an annual community event taking place on Richmond Green. It features entertainment, food retailers, local community organisations and businesses and fairground rides and attractions. Volunteer roles The Poppy Factory has a stall at the event where we sell items from the shop, raise awareness of our work to the local community and promote our upcoming events. We will be looking for a team of volunteers for shifts throughout the day. Volunteers required 9 Trumpeters’ House Trumpeters’ House Garden Party Old Palace Yard, Richmond Green 28 May 2017, 13:00 - 17:30 The event Trumpeters’ House sits on the site of the old Richmond Palace, nestled between Richmond Green and the River Thames. Each year we give visitors the opportunity to explore the beautiful gardens, enjoy tea and cake on the lawn and join in with some garden games. Volunteer roles We are looking for a team of volunteers to help the event run smoothly on the day. There will be a variety of roles that we need help with on the day, including: Ticketing Information stand and guest hosting Running games Serving refreshments Clearing and washing up Volunteers required 25 Armed Forces Week Celebratory Concert St John the Divine Church, Kew Road 21 June 2017, 17:30 - 22:00 The event Each year we hold a summer concert to mark Armed Forces Week, celebrating the work of the Armed Forces and promoting our support of disabled veterans to the local community. -

Edition 0199

Est 2016 London Borough of Richmond upon Thames 0199 Contents TickerTape TwickerSeal C0VID-19 Borough Views History Through Postcards Never Mind - Never Mind - Petition for Richmond and Twickenham Anti-Social Behaviour Letters Twickenham Boatyards Marble Hill Marvels Film Screenings River Crane Sanctury Twickers Foodie Traveller’s Tales WIZ Tales - Samoa Eating Up Life Football Focus Contributors TwickerSeal Alan Winter Graeme Stoten Cllr Geoffrey Samuel TwickWatch Marble Hill House Richmond Film Society Sammi Macqueen Alison Jee Doug Goodman Bruce Lyons Mark Aspen James Dowden LBRuT Editors Berkley Driscoll Teresa Read 28th August 2020 TwickerRobin Photo by Berkley Driscoll TickerTape - News in Brief Pop-up coronavirus test centre available in Richmond this September People who think they may have contracted coronavirus can get tested at a temporary pop-up testing centre in Old Deer Park, on selected dates this September. You must not turn up without an appointment – if you have not booked you will not be tested. More information on being tested and how to book your test HERE Bank holiday waste and recycling collections one day later Following the Bank Holiday on Monday 31 August, Richmond Council will carry out general waste, food waste and recycling collections for domestic properties one day later than usual. Details HERE Twickenham Riverside Stakeholder Reference Group Meeting On Wednesday a ‘Zoom’ meeting of the Twickenham Riverside Stakeholder Reference Group was held. The council presented drawings and details of “Emerging design changes” of the proposed development. There are a number of changes, mostly driven by flood defences following discussions with the Environment Agency, resulting in the Wharf Lane buildings being pushed back from the river edge. -

Downloaded on 2017-02-12T08:16:26Z

Title Redefining military memorials and commemoration and how they have changed since the 19th century with a focus on Anglo-American practice Author(s) Levesque, J. M. André Publication date 2013 Original citation Levesque, J. M. A. 2013. Redefining military memorials and commemoration and how they have changed since the 19th century with a focus on Anglo-American practice. PhD Thesis, University College Cork. Type of publication Doctoral thesis Link to publisher's http://library.ucc.ie/record=b2095603 version Access to the full text of the published version may require a subscription. Rights © 2013, J. M. André Levesque. http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/3.0/ Embargo information No embargo required Item downloaded http://hdl.handle.net/10468/1677 from Downloaded on 2017-02-12T08:16:26Z REDEFINING MILITARY MEMORIALS AND COMMEMORATION AND HOW THEY HAVE TH CHANGED SINCE THE 19 CENTURY WITH A FOCUS ON ANGLO-AMERICAN PRACTICE Thesis presented for the degree of Ph.D. by Joseph Marc André Levesque, M.A. Completed under the supervision of Dr. Michael B. Cosgrave, School of History, National University of Ireland, Cork Head of School of History – Professor Geoffrey Roberts September 2013 1 2 ABSTRACT ....................................................................................................... 7 INTRODUCTION ............................................................................................. 9 CHAPTER 1 - LITERATURE REVIEW ........................................................ 15 Concepts and Sites of Collective -

Chapter 1: Local Socio-Economic/Demographic Profile

Chapter 1: Local Socio-Economic/Demographic Profile Local Implementation Plan London Borough of Richmond-upon-Thames CHAPTER 1 SOCIO-ECONOMIC/DEMOGRAPHIC PROFILE OF THE BOROUGH 1.1 Demographic Context 1.1.1 The Borough covers an area of 5,095 hectares in southwest London and is the only London Borough spanning both sides of the Thames, with river frontage of 34km. The Borough is made up of a series of towns and villages joined by suburban development, although more than a third of its land is open space. Appendix H – Map 2 provides an overview of the Borough. 1.1.2 The Borough is bordered by the London Boroughs of Hounslow, Hammersmith & Fulham, Wandsworth, and Kingston and to the west, by the Surrey Boroughs of Spelthorne and Elmbridge. 1.2 Key features 1.2.1 The Thames 1.2.1.1 The Thames offers many opportunities for active and passive recreation with public access to 27km of the 34km of riverbank in the Borough either by towpath or riverside open space. In addition, tributaries of the Thames, the Beverley Brook, the River Crane, the Duke of Northumberland's River, the Whitton Brook and the Longford River, all provide additional open space, with riverside walks and associated recreational activities. 1.2.2 Conservation Areas 1.2.2.1 The Borough has 70 Designated Conservation Areas and around 1200 listed buildings and 4,890 Buildings of Townscape Merit, key conservation areas include: • Royal Botanic Gardens Kew • Old Deer Park • The Wetland Centre Barnes • Richmond Park • Bushy Park • Crane Valley Nature Reserve 1.2.2.2 The local community has a clearly expressed view that the Borough’s natural and built environment, which is of the highest quality, should be protected and enhanced. -

3931 Knights Batchelor Service

Westminster Abbey A Service to Mark The Passing of The World War One Generation Wednesday 11 November 2009 10.55 am THE FIRST WORLD WAR At the eleventh hour, on the eleventh day of the eleventh month of 1918, the Armistice signed by Germany and the Allies in Marshal Foch’s railway carriage in the Forest of Compiegne came into effect, bringing to an end the hostilities that had involved millions of people from countries across the world. The First World War had lasted four years, four months, and fourteen days. More than one million men, women, and children, Service and civilian, from across the British Empire lost their lives. The War left an enduring impact on those who survived, and on the nation as a whole as the country struggled to come to terms with loss on such an unimaginable scale. They were determined that the sacrifices of the World War One generation would never be forgotten. In marking the passing of this remarkable generation today, and as the nation falls silent at 11.00 am, we honour that promise. THE PADRE’S FLAG The Union Flag hanging at this service over the Grave of the Unknown Warrior, sometimes called the Padre’s flag, was flown daily on a flag post, used on an improvised altar, or as a covering for the fallen, on the Western Front during the First World War. It covered the coffin of the Unknown Warrior at his funeral on 11 November 1920. After resting for a year on the grave it was presented to the Abbey on Armistice Day 1921 by the Reverend David Railton, the Army chaplain who used it during the war.