This Is Not Just the History of a Cycling Club

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Lake District Classic Rally

Steven & David Byrne : Lake District Classic Rally : Photo - Chris Ellison Chairmans Chat Contents It must be summer because instead of power washing mud off Front Cover : Lake District Classic Rally the car after marshalling on a stage rally I spent an hour vac- Pg. 2 Chairman's Chat uuming dust out of the car after the Greystoke Stages ! Being Pg. 3 Member Club Contacts at the start and later the stop line the dust wasn't too bad until the crew of a low numbered car managed to totally ignore the Pg. 4 More SD34MSG Contacts 3, 2, 1 and stop boards and pass at high speed and covering Pg. 5 Around the Clubs (1) every one and thing in a liberal covering !! Pg. 6 Around the Clubs (2) I would like to welcome Lancashire Automobile Club back to SD34 MSG after they recently rejoined and you can read an Pg. 7 2013 SD34MSG Calendar article about the club on page 13. In anticipation of the club Pg. 8 2013 Championship Rounds at a glance rejoining we had invited their co-promoted 3 Sisters Sprint on Pg. 9 SD34MSG Championship Registration 4th August to our championship but in future the event will automatically be included. Apart from the sprint the club is pri- Pg. 10 2013 SD34 MSG Championship Tables marily involved in historic events so this aspect of our sport will Pg. 11 2013 SD34 MSG Marshals Championship give an interesting addition to our members. Pg. 12 2013 SD34 MSG Inter-Club League SD34 MSG Meeting Highlights Pg. 13 Welcome Back - Lancashire A.C Meeting 17th July 2013 David Bell of Lancashire Automobile Club gave a summary of Pg. -

NR05 Oxford TWAO

OFFICIAL Rule 10(2)(d) Transport and Works Act 1992 The Transport and Works (Applications and Objections Procedure) (England and Wales) Rules 2006 Network Rail (Oxford Station Phase 2 Improvements (Land Only)) Order 202X Report summarising consultations undertaken 1 Introduction 1.1 Network Rail Infrastructure Limited ('Network Rail') is making an application to the Secretary of State for Transport for an order under the Transport and Works Act 1992. The proposed order is termed the Network Rail (Oxford Station Phase 2 Improvements (Land Only)) Order ('the Order'). 1.2 The purpose of the Order is to facilitate improved capacity and capability on the “Oxford Corridor” (Didcot North Junction to Aynho Junction) to meet the Strategic Business Plan objections for capacity enhancement and journey time improvements. As well as enhancements to rail infrastructure, improvements to highways are being undertaken as part of the works. Together, these form part of Oxford Station Phase 2 Improvements ('the Project'). 1.3 The Project forms part of a package of rail enhancement schemes which deliver significant economic and strategic benefits to the wider Oxford area and the country. The enhanced infrastructure in the Oxford area will provide benefits for both freight and passenger services, as well as enable further schemes in this strategically important rail corridor including the introduction of East West Rail services in 2024. 1.4 The works comprised in the Project can be summarised as follows: • Creation of a new ‘through platform’ with improved passenger facilities. • A new station entrance on the western side of the railway. • Replacement of Botley Road Bridge with improvements to the highway, cycle and footways. -

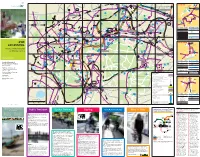

Bus Routes Running Every Day (Black Numbers)

Richmond Bus & Cycle M&G 26/01/2011 15:32 Page 1 2011 ABCDEFGH . E S E A to Heston Y A L Kew Bridge U O L OAD to W N I N N R KEW N Steam G O K BRENTFORD E RICHMOND R O L Ealing 267 V T G I A Museum BRIDGE E 391 Queen T N Y O U N A S A Orange Tree D R T Charlotte S A G S D O . E R 391 P U U O R T E Theatre D S C H R IN B O W H Hall/R.A.C.C. G 267 IS PAR H OAD R L W A . R L G 65 DE N A G K RO SYON LANE E IC T OLDHAW A Parkshot N E V R S GUNNERSBURY K CHISWICK D W O E D 267 T M D . N R E T Y 111 R O 65 BRIDGE ROAD BATH ROAD B P O . KEW K A H E PARK K GOLDHAWK ROAD W AT D T R D O H E M I W D H A W G R 267 E E H A L A A D LE G L R S H O R L 267 T R T D EY Little E I O O RE D R U HIGH ST ROAD N A Waterman’s R RO 391 TURNHAM L A H37.110 A D P B Green N A O S D Library R D Arts Centre G O GREEN D RICHMOND T H22 281 H37 OAD Kew Green W R E STAMFORD A G School K Richmond C U N STATION I ‘Bell’ Bus Station D DON 65 BROOK Richmond Q L A LON Green L R O B D E U N Theatre E 1 391 S CE A H RAVENSCOURT 1 E H D T E H to Hatton Cross and W LONDON D Main W A O R T HIGH STREET Thornbury A RS R R G S Kew Palace O Falcons PARK Heathrow Airport ISLEWORTH O Gate D O R O to F B Playing T R O D N E H37 A A ROAD H22 . -

German Jews in the United States: a Guide to Archival Collections

GERMAN HISTORICAL INSTITUTE,WASHINGTON,DC REFERENCE GUIDE 24 GERMAN JEWS IN THE UNITED STATES: AGUIDE TO ARCHIVAL COLLECTIONS Contents INTRODUCTION &ACKNOWLEDGMENTS 1 ABOUT THE EDITOR 6 ARCHIVAL COLLECTIONS (arranged alphabetically by state and then city) ALABAMA Montgomery 1. Alabama Department of Archives and History ................................ 7 ARIZONA Phoenix 2. Arizona Jewish Historical Society ........................................................ 8 ARKANSAS Little Rock 3. Arkansas History Commission and State Archives .......................... 9 CALIFORNIA Berkeley 4. University of California, Berkeley: Bancroft Library, Archives .................................................................................................. 10 5. Judah L. Mages Museum: Western Jewish History Center ........... 14 Beverly Hills 6. Acad. of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences: Margaret Herrick Library, Special Coll. ............................................................................ 16 Davis 7. University of California at Davis: Shields Library, Special Collections and Archives ..................................................................... 16 Long Beach 8. California State Library, Long Beach: Special Collections ............. 17 Los Angeles 9. John F. Kennedy Memorial Library: Special Collections ...............18 10. UCLA Film and Television Archive .................................................. 18 11. USC: Doheny Memorial Library, Lion Feuchtwanger Archive ................................................................................................... -

ANNOUNCEMENTS by the MAYOR 1. on 5Th July 2012, I Was Delighted

ANNOUNCEMENTS BY THE MAYOR th 1. On 5 July 2012, I was delighted to attend Ealing Hammersmith & West London College, LLDD Awards Ceremony, Colet Gardens, W14 th 2. On 5 July, I attended the Standing Together event, Small Hall, HTH, W6 th 3. On 5 July, I was delighted to host and present with Cllr Greg Smith, HM The Queen’s (1952-2012) Diamond Jubilee Medals to members of staff from Parks Constabulary H&F, Mayor’s Parlour, HTH W6 th 4. On 5 July, accompanied by my consort, I attended The Regimental Cocktail Party, The Guards Museum, Wellington Barracks, Birdcage Walk SW1 th 5. On 6 July, I attended the Kumon Education Award Ceremony, W12 th 6. On 6 July, I attended the Mayor of Ealing’s Charity event, Ealing Town Hall, W5 th 7. On 7 July, accompanied by Cllr Frances Stainton, Deputy Mayor, I attended and officially opened ‘Fair on the Green’, Parsons Green, SW6 th 8. On 7 July, I attended All Saints School event, Bishops Park, SW6 th 9. On 7 July, I attended the National Childbirth Trust and Putney Branch Charity Fun Walk, FFC, SW6 th 10. On 7 July, I attended Addison Primary School event, W14 th 11. On 8 July, I attended the ‘Paggs Cup’ Football Tournament, South Park, SW6 th st 12. On 9 July, I attended the 21 Fulham Brownies charity cake sale in aid of Dementia UK, St Dionis Church Hall, St Dionis Road, SW6 th 13. On 9 July, I attended and spoke at the Business Awards, Basra Restaurant, W6 th 14. -

WIN a ONE NIGHT STAY at the OXFORD MALMAISON | OXFORDSHIRE THAMES PATH | FAMILY FUN Always More to Discover

WIN A ONE NIGHT STAY AT THE OXFORD MALMAISON | OXFORDSHIRE THAMES PATH | FAMILY FUN Always more to discover Tours & Exhibitions | Events | Afternoon Tea Birthplace of Sir Winston Churchill | World Heritage Site BUY ONE DAY, GET 12 MONTHS FREE ATerms precious and conditions apply.time, every time. Britain’sA precious time,Greatest every time.Palace. Britain’s Greatest Palace. www.blenheimpalace.com Contents 4 Oxford by the Locals Get an insight into Oxford from its locals. 8 72 Hours in the Cotswolds The perfect destination for a long weekend away. 12 The Oxfordshire Thames Path Take a walk along the Thames Path and enjoy the most striking riverside scenery in the county. 16 Film & TV Links Find out which famous films and television shows were filmed around the county. 19 Literary Links From Alice in Wonderland to Lord of the Rings, browse literary offerings and connections that Oxfordshire has created. 20 Cherwell the Impressive North See what North Oxfordshire has to offer visitors. 23 Traditions Time your visit to the county to experience at least one of these traditions! 24 Transport Train, coach, bus and airport information. 27 Food and Drink Our top picks of eateries in the county. 29 Shopping Shopping hotspots from around the county. 30 Family Fun Farm parks & wildlife, museums and family tours. 34 Country Houses and Gardens Explore the stories behind the people from country houses and gardens in Oxfordshire. 38 What’s On See what’s on in the county for 2017. 41 Accommodation, Tours Broughton Castle and Attraction Listings Welcome to Oxfordshire Connect with Experience Oxfordshire From the ancient University of Oxford to the rolling hills of the Cotswolds, there is so much rich history and culture for you to explore. -

Apartment 3, 91 Islip Road, North Oxford, OX2 7SQ Maps

Apartment 3, 91 Islip Road, North Oxford, OX2 7SQ maps Immaculately presented purpose built apartment situated in a small select development. The spacious accommodation comprises two double bedrooms including an ensuite shower room to the master bedroom, a contemporary style bathroom, a light open plan kitchen and southerly facing living area, and secure gated parking to the rear. The property is conveniently located for access to Oxford City Centre and the Summertown shopping parade and many amenities. Bedrooms 2 | Bathrooms 2 | Receptions 1 maps Key features • Fitted Kitchen with Integrated Washer Dryer, Fridge Freezer, Oven & Electric Hob • Open Plan Kitchen Living Area with Southerly Aspect • Wooden Flooring to the Hallway & Kitchen Living Room • Two Double Bedrooms; with Fitted Wardrobes & a Patio Door in the Master Bedroom • Contemporary White Suite Bathroom with Over Shower & Ensuite Shower Room • Gas Central Heating to Radiators • Double Glazing Throughout • Allocated Gated Parking Space & Bike Store • Video Entry Phone • Leasehold Location Summertown Shops c. 0.6 miles, Oxford City Centre c. 2.3 miles, Oxford Parkway Railway Station (Mainline Marylebone) c. 1. 8 miles, Oxford Railway Station (Mainline Paddington) c. 2.8 miles, London & Airport Buses c. 2.3 miles, M40 Junction 8a c. 9.1 miles For more information or to arrange a viewing contact: Nicola Horner The following details have been prepared in good faith, they are not intended to constitute 205a Banbury Road part of an offer of contract. Any information contained herein (whether in text, plans or Summertown, Oxford OX2 7HQ photographs) is given in good faith but should not be relied upon as being a statement of T: 01865 553900 representation of fact. -

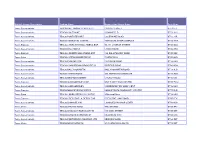

Multiple Group Description Trading Name Number and Street Name

Multiple Group Description Trading Name Number And Street Name Post Code Tesco Supermarkets TESCO BALLYMONEY CASTLE ST CASTLE STREET BT53 6JT Tesco Supermarkets TESCO COLERAINE 2 BANNFIELD BT52 1HU Tesco Supermarkets TESCO PORTSTEWART COLERAINE ROAD BT55 7JR Tesco Supermarkets TESCO YORKGATE CENTRE YORKGATE SHOP COMPLEX BT15 1WA Tesco Express TESCO CHURCH ST BALLYMENA EXP 99-111 CHURCH STREET BT43 8DG Tesco Supermarkets TESCO BALLYMENA LARNE ROAD BT42 3HB Tesco Express TESCO CARNINY BALLYMENA EXP 144 BALLYMONEY ROAD BT43 5BZ Tesco Extra TESCO ANTRIM MASSEREENE CASTLEWAY BT41 4AB Tesco Supermarkets TESCO ENNISKILLEN 11 DUBLIN ROAD BT74 6HN Tesco Supermarkets TESCO COOKSTOWN BROADFIELD ORRITOR ROAD BT80 8BH Tesco Supermarkets TESCO BALLYGOMARTIN BALLYGOMARTIN ROAD BT13 3LD Tesco Supermarkets TESCO ANTRIM ROAD 405 ANTRIM RD STORE439 BT15 3BG Tesco Supermarkets TESCO NEWTOWNABBEY CHURCH ROAD BT36 6YJ Tesco Express TESCO GLENGORMLEY EXP UNIT 5 MAYFIELD CENTRE BT36 7WU Tesco Supermarkets TESCO GLENGORMLEY CARNMONEY RD SHOP CENT BT36 6HD Tesco Express TESCO MONKSTOWN EXPRES MONKSTOWN COMMUNITY CENTRE BT37 0LG Tesco Extra TESCO CARRICKFERGUS CASTLE 8 Minorca Place BT38 8AU Tesco Express TESCO CRESCENT LK DERRY EXP CRESCENT LINK ROAD BT47 5FX Tesco Supermarkets TESCO LISNAGELVIN LISNAGELVIN SHOP CENTR BT47 6DA Tesco Metro TESCO STRAND ROAD THE STRAND BT48 7PY Tesco Supermarkets TESCO LIMAVADY ROEVALLEY NI 119 MAIN STREET BT49 0ET Tesco Supermarkets TESCO LURGAN CARNEGIE ST MILLENIUM WAY BT66 6AS Tesco Supermarkets TESCO PORTADOWN MEADOW CTR MEADOW -

Council Letter Template

Agenda Item 4 WEST AREA PLANNING COMMITTEE 7th July 2020 Application number: 20/00182/VAR Decision due by 25th March 2020 Extension of time To be agreed Proposal Removal of condition 7 (Time limit of 6 years from occupation) of planning permission 15/03087/VAR (Variation of condition 7 (Time limit of 3 years) of prior approval 15/00096/PA18 (Application seeking prior approval for development comprising extension to the length of existing north bay platforms, replacement platform canopies, new re-locatable rail staff accommodation building and reconfiguration of short stay and staff car parking under Part 11 Class A Schedule 2 of the Town and Country Planning (General Permitted Development) Order 1995.)) to allow the approved TOC accommodation building to remain permanently.(amended description) Site address Oxford Railway Station , Park End Street, Oxford, OX1 1HS – see Appendix 1 for site plan Ward Jericho And Osney Ward Case officer Robert Fowler Agent: N/A Applicant: Mr Ian Wheaton Reason at Committee The application is before the committee because the previous decision to grant planning permission for the building was approved at committee (15/00096/PA11); this application represents a significant amendment to that application. 1. RECOMMENDATION 1.1. West Area Planning Committee is recommended to: 1.1.1. approve the application for the reasons given in the report and subject to the required planning conditions set out in section 12 of this report and grant planning permission. 1.1.2. agree to delegate authority to the Head of Planning Services to: finalise the recommended conditions as set out in this report including such refinements, amendments, additions and/or deletions as the Head of 97 Planning Services considers reasonably necessary 2. -

Members' Directory

ROYAL WARRANT HOLDERS ASSOCIATION MEMBERS’ DIRECTORY 2019–2020 SECRETARY’S FOREWORD 3 WELCOME Dear Reader, The Royal Warrant Holders Association represents one of the most diverse groups of companies in the world in terms of size and sector, from traditional craftspeople to global multinationals operating at the cutting edge of technology. The Members’ Directory lists companies by broad categories that further underline the range of skills, products and services that exist within the membership. Also included is a section dedicated to our principal charitable arm, the Queen Elizabeth Scholarship Trust (QEST), of which HRH The Prince of Wales is Patron. The section profiles the most recent alumni of scholars and apprentices to have benefited from funding, who have each developed their skills and promoted excellence in British craftsmanship. As ever, Royal Warrant holders and QEST are united in our dedication to service, quality and excellence as symbolised by the Royal Warrant of Appointment. We hope you find this printed directory of use when thinking of manufacturers and suppliers of products and services. An online version – which is regularly updated with company information and has enhanced search facilities – can be viewed on our website, www.royalwarrant.org “UNITED IN OUR DEDICATION TO Richard Peck SERVICE, QUALITY CEO & Secretary AND EXCELLENCE” The Royal Warrant Holders Association CONTENTS Directory of members Agriculture & Animal Welfare ...............................................................................................5 -

Monarch Assurance International Open Chess

Isle of Man (IoM) Open The event of 2016 definitely got the Isle of Man back on the international chess map! Isle of Man (IoM) Open has been played under three different labels: Monarch Assurance International Open Chess Tournament at the Cherry Orchard Hotel (1st-10th), later Ocean Castle Hotel (11th-16th), always in Port Erin (1993 – 2007, in total 16 annual editions) PokerStars Isle of Man International (2014 & 15) in the Royal Hall at the Villa Marina in Douglas Chess.com Isle of Man International (since 2016) in the Royal Hall at the Villa Marina in Douglas The Isle of Man is a self-governing Crown dependency in the Irish Sea between England and Northern Ireland. The island has been inhabited since before 6500 BC. In the 9th century, Norsemen established the Kingdom of the Isles. Magnus III, King of Norway, was also known as King of Mann and the Isles between 1099 and 1103. In 1266, the island became part of Scotland and came under the feudal lordship of the English Crown in 1399. It never became part of the Kingdom of Great Britain or its successor the United Kingdom, retaining its status as an internally self-governing Crown dependency. http://iominternationalchess.com/ For a small country, sport in the Isle of Man plays an important part in making the island known to the wider world. The principal international sporting event held on the island is the annual Isle of Man TT motorcycling event: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Sport_in_the_Isle_of_Man#Other_sports Isle of Man also organized the 1st World Senior Team Chess Championship, In Port Erin, Isle Of Man, 5-12 October 2004 http://www.saund.co.uk/britbase/worldseniorteam2004/ Korchnoi who had to hurry up to the forthcoming 2004 Chess Olympiad at Calvià, agreed to play the first four days for the team of Switzerland which took finally the bronze medal, performing at 3.5/4, drawing vs. -

Healing Hidden Wounds

Veterans WORLD Issue 35 HEALING HIDDEN WOUNDS www.gov.uk/veterans-uk You can now find information about Veterans UK on GOV.UK. Whether you want information about how to apply for a medal, or need more urgent assistance as a veteran in a crisis, the Veterans UK webpages have information to help you. For further information please email [email protected] or call the Veterans UK Helpline on 0808 1914 2 18. July 2015 Veterans WORLD “However old you are, pick up the phone and get support. What’s the worst that could happen?” Update - Page 6 - Page 10 Dave Latimer 14 COntentS 4 News 6 The Armed Forces Covenant 8 Supporting, Enabling and Empowering 9 Pensions for Life 10 Healing Hidden Wounds 12 12 Driving Forward Employability for Veterans 14 Turn to Starboard to get back on track 16 RAF Veterans aided by new Advice Service 17 Pop-In for free advice 18 Welfare Staff out and about on Armed Forces Day 2015 The content of Veterans WORLD is provided to raise awareness of help, advice and support available to the 18 veterans community. Publication of articles on services Veterans World is distributed to those who work in an For information relating to War Pension/AFCS advisory role. claims please call the Veterans UK Helpline: provided or developments affecting To contact the Editor: 0808 1914 2 18. the veterans community does not Email: [email protected] mean that they are endorsed by For advertising opportunities please Email: Veterans WORLD or the Ministry of Want to make an editorial contribution? [email protected] Defence.