Proceedings of the Indiana Academy of Science

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Abacca Mosaic Virus

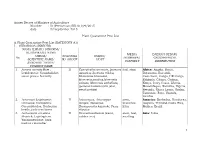

Annex Decree of Ministry of Agriculture Number : 51/Permentan/KR.010/9/2015 date : 23 September 2015 Plant Quarantine Pest List A. Plant Quarantine Pest List (KATEGORY A1) I. SERANGGA (INSECTS) NAMA ILMIAH/ SINONIM/ KLASIFIKASI/ NAMA MEDIA DAERAH SEBAR/ UMUM/ GOLONGA INANG/ No PEMBAWA/ GEOGRAPHICAL SCIENTIFIC NAME/ N/ GROUP HOST PATHWAY DISTRIBUTION SYNONIM/ TAXON/ COMMON NAME 1. Acraea acerata Hew.; II Convolvulus arvensis, Ipomoea leaf, stem Africa: Angola, Benin, Lepidoptera: Nymphalidae; aquatica, Ipomoea triloba, Botswana, Burundi, sweet potato butterfly Merremiae bracteata, Cameroon, Congo, DR Congo, Merremia pacifica,Merremia Ethiopia, Ghana, Guinea, peltata, Merremia umbellata, Kenya, Ivory Coast, Liberia, Ipomoea batatas (ubi jalar, Mozambique, Namibia, Nigeria, sweet potato) Rwanda, Sierra Leone, Sudan, Tanzania, Togo. Uganda, Zambia 2. Ac rocinus longimanus II Artocarpus, Artocarpus stem, America: Barbados, Honduras, Linnaeus; Coleoptera: integra, Moraceae, branches, Guyana, Trinidad,Costa Rica, Cerambycidae; Herlequin Broussonetia kazinoki, Ficus litter Mexico, Brazil beetle, jack-tree borer elastica 3. Aetherastis circulata II Hevea brasiliensis (karet, stem, leaf, Asia: India Meyrick; Lepidoptera: rubber tree) seedling Yponomeutidae; bark feeding caterpillar 1 4. Agrilus mali Matsumura; II Malus domestica (apel, apple) buds, stem, Asia: China, Korea DPR (North Coleoptera: Buprestidae; seedling, Korea), Republic of Korea apple borer, apple rhizome (South Korea) buprestid Europe: Russia 5. Agrilus planipennis II Fraxinus americana, -

A Checklist of the Vascular Flora of the Mary K. Oxley Nature Center, Tulsa County, Oklahoma

Oklahoma Native Plant Record 29 Volume 13, December 2013 A CHECKLIST OF THE VASCULAR FLORA OF THE MARY K. OXLEY NATURE CENTER, TULSA COUNTY, OKLAHOMA Amy K. Buthod Oklahoma Biological Survey Oklahoma Natural Heritage Inventory Robert Bebb Herbarium University of Oklahoma Norman, OK 73019-0575 (405) 325-4034 Email: [email protected] Keywords: flora, exotics, inventory ABSTRACT This paper reports the results of an inventory of the vascular flora of the Mary K. Oxley Nature Center in Tulsa, Oklahoma. A total of 342 taxa from 75 families and 237 genera were collected from four main vegetation types. The families Asteraceae and Poaceae were the largest, with 49 and 42 taxa, respectively. Fifty-eight exotic taxa were found, representing 17% of the total flora. Twelve taxa tracked by the Oklahoma Natural Heritage Inventory were present. INTRODUCTION clayey sediment (USDA Soil Conservation Service 1977). Climate is Subtropical The objective of this study was to Humid, and summers are humid and warm inventory the vascular plants of the Mary K. with a mean July temperature of 27.5° C Oxley Nature Center (ONC) and to prepare (81.5° F). Winters are mild and short with a a list and voucher specimens for Oxley mean January temperature of 1.5° C personnel to use in education and outreach. (34.7° F) (Trewartha 1968). Mean annual Located within the 1,165.0 ha (2878 ac) precipitation is 106.5 cm (41.929 in), with Mohawk Park in northwestern Tulsa most occurring in the spring and fall County (ONC headquarters located at (Oklahoma Climatological Survey 2013). -

LUNDY FUNGI: FURTHER SURVEYS 2004-2008 by JOHN N

Journal of the Lundy Field Society, 2, 2010 LUNDY FUNGI: FURTHER SURVEYS 2004-2008 by JOHN N. HEDGER1, J. DAVID GEORGE2, GARETH W. GRIFFITH3, DILUKA PEIRIS1 1School of Life Sciences, University of Westminster, 115 New Cavendish Street, London, W1M 8JS 2Natural History Museum, Cromwell Road, London, SW7 5BD 3Institute of Biological Environmental and Rural Sciences, University of Aberystwyth, SY23 3DD Corresponding author, e-mail: [email protected] ABSTRACT The results of four five-day field surveys of fungi carried out yearly on Lundy from 2004-08 are reported and the results compared with the previous survey by ourselves in 2003 and to records made prior to 2003 by members of the LFS. 240 taxa were identified of which 159 appear to be new records for the island. Seasonal distribution, habitat and resource preferences are discussed. Keywords: Fungi, ecology, biodiversity, conservation, grassland INTRODUCTION Hedger & George (2004) published a list of 108 taxa of fungi found on Lundy during a five-day survey carried out in October 2003. They also included in this paper the records of 95 species of fungi made from 1970 onwards, mostly abstracted from the Annual Reports of the Lundy Field Society, and found that their own survey had added 70 additional records, giving a total of 156 taxa. They concluded that further surveys would undoubtedly add to the database, especially since the autumn of 2003 had been exceptionally dry, and as a consequence the fruiting of the larger fleshy fungi on Lundy, especially the grassland species, had been very poor, resulting in under-recording. Further five-day surveys were therefore carried out each year from 2004-08, three in the autumn, 8-12 November 2004, 4-9 November 2007, 3-11 November 2008, one in winter, 23-27 January 2006 and one in spring, 9-16 April 2005. -

State of New York City's Plants 2018

STATE OF NEW YORK CITY’S PLANTS 2018 Daniel Atha & Brian Boom © 2018 The New York Botanical Garden All rights reserved ISBN 978-0-89327-955-4 Center for Conservation Strategy The New York Botanical Garden 2900 Southern Boulevard Bronx, NY 10458 All photos NYBG staff Citation: Atha, D. and B. Boom. 2018. State of New York City’s Plants 2018. Center for Conservation Strategy. The New York Botanical Garden, Bronx, NY. 132 pp. STATE OF NEW YORK CITY’S PLANTS 2018 4 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY 6 INTRODUCTION 10 DOCUMENTING THE CITY’S PLANTS 10 The Flora of New York City 11 Rare Species 14 Focus on Specific Area 16 Botanical Spectacle: Summer Snow 18 CITIZEN SCIENCE 20 THREATS TO THE CITY’S PLANTS 24 NEW YORK STATE PROHIBITED AND REGULATED INVASIVE SPECIES FOUND IN NEW YORK CITY 26 LOOKING AHEAD 27 CONTRIBUTORS AND ACKNOWLEGMENTS 30 LITERATURE CITED 31 APPENDIX Checklist of the Spontaneous Vascular Plants of New York City 32 Ferns and Fern Allies 35 Gymnosperms 36 Nymphaeales and Magnoliids 37 Monocots 67 Dicots 3 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY This report, State of New York City’s Plants 2018, is the first rankings of rare, threatened, endangered, and extinct species of what is envisioned by the Center for Conservation Strategy known from New York City, and based on this compilation of The New York Botanical Garden as annual updates thirteen percent of the City’s flora is imperiled or extinct in New summarizing the status of the spontaneous plant species of the York City. five boroughs of New York City. This year’s report deals with the City’s vascular plants (ferns and fern allies, gymnosperms, We have begun the process of assessing conservation status and flowering plants), but in the future it is planned to phase in at the local level for all species. -

Explain Kotar Classification

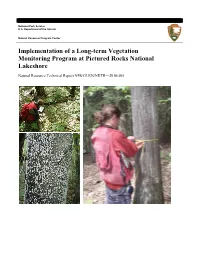

National Park Service U.S. Department of the Interior Natural Resource Program Center Implementation of a Long-term Vegetation Monitoring Program at Pictured Rocks National Lakeshore Natural Resource Technical Report NPS/GLKN/NRTR—2010/405 ON THE COVER Clockwise from top left: recording the groundlayer in 1m2 quadrat; measuring tree DBH; beech bark disease. Photographs by: GLKN vegetation monitoring field crew Implementation of a Long-term Vegetation Monitoring Program at Pictured Rocks National Lakeshore Natural Resource Technical Report NPS/GLKN/NRTR—2010/405 Suzanne Sanders and Jessica Grochowski National Park Service Great Lakes Inventory & Monitoring Network 2800 Lake Shore Dr. East Ashland, WI 54806 FortNovember Collins, 2010 Colorado U.S. Department of the Interior National Park Service Natural Resource Program Center Fort Collins, Colorado The National Park Service, Natural Resource Program Center publishes a range of reports that address natural resource topics of interest and applicability to a broad audience in the National Park Service and others in natural resource management, including scientists, conservation and environmental constituencies, and the public. The Natural Resource Technical Report Series is used to disseminate results of scientific studies in the physical, biological, and social sciences for both the advancement of science and the achievement of the National Park Service mission. The series provides contributors with a forum for displaying comprehensive data that are often deleted from journals because of page limitations. All manuscripts in the series receive the appropriate level of peer review to ensure that the information is scientifically credible, technically accurate, appropriately written for the intended audience, and designed and published in a professional manner. -

Vascular Plant Inventory of Mount Rainier National Park

National Park Service U.S. Department of the Interior Natural Resource Program Center Vascular Plant Inventory of Mount Rainier National Park Natural Resource Technical Report NPS/NCCN/NRTR—2010/347 ON THE COVER Mount Rainier and meadow courtesy of 2007 Mount Rainier National Park Vegetation Crew Vascular Plant Inventory of Mount Rainier National Park Natural Resource Technical Report NPS/NCCN/NRTR—2010/347 Regina M. Rochefort North Cascades National Park Service Complex 810 State Route 20 Sedro-Woolley, Washington 98284 June 2010 U.S. Department of the Interior National Park Service Natural Resource Program Center Fort Collins, Colorado The National Park Service, Natural Resource Program Center publishes a range of reports that address natural resource topics of interest and applicability to a broad audience in the National Park Service and others in natural resource management, including scientists, conservation and environmental constituencies, and the public. The Natural Resource Technical Report Series is used to disseminate results of scientific studies in the physical, biological, and social sciences for both the advancement of science and the achievement of the National Park Service mission. The series provides contributors with a forum for displaying comprehensive data that are often deleted from journals because of page limitations. All manuscripts in the series receive the appropriate level of peer review to ensure that the information is scientifically credible, technically accurate, appropriately written for the intended audience, and designed and published in a professional manner. This report received informal peer review by subject-matter experts who were not directly involved in the collection, analysis, or reporting of the data. -

The New York Botanical Garden

Vol. XV DECEMBER, 1914 No. 180 JOURNAL The New York Botanical Garden EDITOR ARLOW BURDETTE STOUT Director of the Laboratories CONTENTS PAGE Index to Volumes I-XV »33 PUBLISHED FOR THE GARDEN AT 41 NORTH QUBKN STRHBT, LANCASTER, PA. THI NEW ERA PRINTING COMPANY OFFICERS 1914 PRESIDENT—W. GILMAN THOMPSON „ „ _ i ANDREW CARNEGIE VICE PRESIDENTS J FRANCIS LYNDE STETSON TREASURER—JAMES A. SCRYMSER SECRETARY—N. L. BRITTON BOARD OF- MANAGERS 1. ELECTED MANAGERS Term expires January, 1915 N. L. BRITTON W. J. MATHESON ANDREW CARNEGIE W GILMAN THOMPSON LEWIS RUTHERFORD MORRIS Term expire January. 1916 THOMAS H. HUBBARD FRANCIS LYNDE STETSON GEORGE W. PERKINS MVLES TIERNEY LOUIS C. TIFFANY Term expire* January, 1917 EDWARD D. ADAMS JAMES A. SCRYMSER ROBERT W. DE FOREST HENRY W. DE FOREST J. P. MORGAN DANIEL GUGGENHEIM 2. EX-OFFICIO MANAGERS THE MAYOR OP THE CITY OF NEW YORK HON. JOHN PURROY MITCHEL THE PRESIDENT OP THE DEPARTMENT OP PUBLIC PARES HON. GEORGE CABOT WARD 3. SCIENTIFIC DIRECTORS PROF. H. H. RUSBY. Chairman EUGENE P. BICKNELL PROF. WILLIAM J. GIES DR. NICHOLAS MURRAY BUTLER PROF. R. A. HARPER THOMAS W. CHURCHILL PROF. JAMES F. KEMP PROF. FREDERIC S. LEE GARDEN STAFF DR. N. L. BRITTON, Director-in-Chief (Development, Administration) DR. W. A. MURRILL, Assistant Director (Administration) DR. JOHN K. SMALL, Head Curator of the Museums (Flowering Plants) DR. P. A. RYDBERG, Curator (Flowering Plants) DR. MARSHALL A. HOWE, Curator (Flowerless Plants) DR. FRED J. SEAVER, Curator (Flowerless Plants) ROBERT S. WILLIAMS, Administrative Assistant PERCY WILSON, Associate Curator DR. FRANCIS W. PENNELL, Associate Curator GEORGE V. -

Grasses-Accts 4

MELICA Oniongrass The name Melica comes directly from the Italian name for a kind of sorghum. The genus Melica resembles Bromus in the overall appearance of the flowerhead, which may vary from a form with open spreading branches to a tight, slightly closed spike. To confuse things even more, Melica smithii has two small teeth at the tip of the lemma where the awn meets the lemma, which is a standard character used to differentiate Bromus from other genera. The two genera differ in that Melica has spikelets with two to four sterile flowers above the fertile flowers and these are almost like scales. This gives the spikelet a more pointed or sometimes a more open appearance because the lemma is not full. The glumes are shorter than the first lemma and are thin, papery, and transparent. The sheath is closed to near the point where it meets the blade. The ligules are membrane-like and often closed in the front. In addition, there are no auricles and the callus is not bearded. This genus has a few species that are bulbous at the base of the stem. Important features to look for are the bulbous stem base and whether or not awns are present. Three of the four species of Melica found in the Columbia Basin region are Blue listed by the B.C. Conservation Database Centre in Douglas et al. (1998). In some cases this rarity is the result of the type of specialized habitat re- quirements of the species. In other cases, the species are at the limit of their range. -

Report on RPD No

report on RPD No. 627 PLANT February 1982 DEPARTMENT OF CROP SCIENCES DISEASE UNIVERSITY OF ILLINOIS AT URBANA-CHAMPAIGN HOLLYHOCK RUST Rust caused by the fungus Puccinia malvacearum is the most common and widespread disease of hollyhock (Althaea rosea). Hollyhock rust was first reported in 1852 in Chile, where it is indigenous. In 1857 it was observed in Australia, and in 1869 in Spain, from where it spread rapidly over the rest of Europe. By 1875, rust was reported in South Africa, and it reached the United States in 1886. Today, the disease occurs worldwide. Severely rusted leaves turn yellow, wither, and drop prematurely. Ragged and unsightly plants result, but Figure 1. Hollyhock rust pustules (sori) on the upper hollyhocks infected with rust are rarely killed. It is not and lower sides of hollyhock leaf. uncommon to find the disease severe in the spring and autumn but declining in midsummer, especially during drought periods. The same rust fungus attacks about fifty species in ten genera of the mallow family (Malvaceae) including species of Althaea, Brotex, Kitaibelia, Lavatera, Malope, Malva, Malvastrum, and Sidalcea. Rust is prevalent on common or roundleaf mallow (Malva rotundifolia), a common weed closely related to hollyhock. SYMPTOMS Rust first appears primarily on the undersides of the lower leaves as lemon yellow to orange, almost waxy pustules (or sori) that turn reddish brown to chocolate brown with age. Larger, bright yellow to orange spots with reddish centers develop on the leaf surface opposite the pustules. The rust quickly spreads to other leaves, which become covered with small, reddish brown to chocolate brown pustules. -

Part 2 – Fruticose Species

Appendix 5.2-1 Vegetation Technical Appendix APPENDIX 5.2‐1 Vegetation Technical Appendix Contents Section Page Ecological Land Classification ............................................................................................................ A5.2‐1‐1 Geodatabase Development .............................................................................................. A5.2‐1‐1 Vegetation Community Mapping ..................................................................................... A5.2‐1‐1 Quality Assurance and Quality Control ............................................................................ A5.2‐1‐3 Limitations of Ecological Land Classification .................................................................... A5.2‐1‐3 Field Data Collection ......................................................................................................... A5.2‐1‐3 Supplementary Results ..................................................................................................... A5.2‐1‐4 Rare Vegetation Species and Rare Ecological Communities ........................................................... A5.2‐1‐10 Supplementary Desktop Results ..................................................................................... A5.2‐1‐10 Field Methods ................................................................................................................. A5.2‐1‐16 Supplementary Results ................................................................................................... A5.2‐1‐17 Weed Species -

Floristic Quality Assessment Report

FLORISTIC QUALITY ASSESSMENT IN INDIANA: THE CONCEPT, USE, AND DEVELOPMENT OF COEFFICIENTS OF CONSERVATISM Tulip poplar (Liriodendron tulipifera) the State tree of Indiana June 2004 Final Report for ARN A305-4-53 EPA Wetland Program Development Grant CD975586-01 Prepared by: Paul E. Rothrock, Ph.D. Taylor University Upland, IN 46989-1001 Introduction Since the early nineteenth century the Indiana landscape has undergone a massive transformation (Jackson 1997). In the pre-settlement period, Indiana was an almost unbroken blanket of forests, prairies, and wetlands. Much of the land was cleared, plowed, or drained for lumber, the raising of crops, and a range of urban and industrial activities. Indiana’s native biota is now restricted to relatively small and often isolated tracts across the State. This fragmentation and reduction of the State’s biological diversity has challenged Hoosiers to look carefully at how to monitor further changes within our remnant natural communities and how to effectively conserve and even restore many of these valuable places within our State. To meet this monitoring, conservation, and restoration challenge, one needs to develop a variety of appropriate analytical tools. Ideally these techniques should be simple to learn and apply, give consistent results between different observers, and be repeatable. Floristic Assessment, which includes metrics such as the Floristic Quality Index (FQI) and Mean C values, has gained wide acceptance among environmental scientists and decision-makers, land stewards, and restoration ecologists in Indiana’s neighboring states and regions: Illinois (Taft et al. 1997), Michigan (Herman et al. 1996), Missouri (Ladd 1996), and Wisconsin (Bernthal 2003) as well as northern Ohio (Andreas 1993) and southern Ontario (Oldham et al. -

Baja California, Mexico, and a Vegetation Map of Colonet Mesa Alan B

Aliso: A Journal of Systematic and Evolutionary Botany Volume 29 | Issue 1 Article 4 2011 Plants of the Colonet Region, Baja California, Mexico, and a Vegetation Map of Colonet Mesa Alan B. Harper Terra Peninsular, Coronado, California Sula Vanderplank Rancho Santa Ana Botanic Garden, Claremont, California Mark Dodero Recon Environmental Inc., San Diego, California Sergio Mata Terra Peninsular, Coronado, California Jorge Ochoa Long Beach City College, Long Beach, California Follow this and additional works at: http://scholarship.claremont.edu/aliso Part of the Biodiversity Commons, Botany Commons, and the Ecology and Evolutionary Biology Commons Recommended Citation Harper, Alan B.; Vanderplank, Sula; Dodero, Mark; Mata, Sergio; and Ochoa, Jorge (2011) "Plants of the Colonet Region, Baja California, Mexico, and a Vegetation Map of Colonet Mesa," Aliso: A Journal of Systematic and Evolutionary Botany: Vol. 29: Iss. 1, Article 4. Available at: http://scholarship.claremont.edu/aliso/vol29/iss1/4 Aliso, 29(1), pp. 25–42 ’ 2011, Rancho Santa Ana Botanic Garden PLANTS OF THE COLONET REGION, BAJA CALIFORNIA, MEXICO, AND A VEGETATION MAPOF COLONET MESA ALAN B. HARPER,1 SULA VANDERPLANK,2 MARK DODERO,3 SERGIO MATA,1 AND JORGE OCHOA4 1Terra Peninsular, A.C., PMB 189003, Suite 88, Coronado, California 92178, USA ([email protected]); 2Rancho Santa Ana Botanic Garden, 1500 North College Avenue, Claremont, California 91711, USA; 3Recon Environmental Inc., 1927 Fifth Avenue, San Diego, California 92101, USA; 4Long Beach City College, 1305 East Pacific Coast Highway, Long Beach, California 90806, USA ABSTRACT The Colonet region is located at the southern end of the California Floristic Province, in an area known to have the highest plant diversity in Baja California.