What We Talk About When We Talk About Football by Luke Healey

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

“No Protest During Festive Season”

No326 K10 www.diggers.news Tuesday December 11, 2018 By Mirriam Chabala Police in Lusaka have denied the nine opposition political parties permission to conduct a peaceful protest against government expenditure of public resources, citing limited manpower in the service to protect them this festive season. Speaking shortly a er a POLICE STOP meeting with Lusaka Police Commissioner Nelson Phiri, ADD president Charles Milupi, who spoke on behalf of the other parties expressed disappointment that Police could deny them a permit when they had followed the necessary procedure. OPPOSITION Story page 4 “No protest during festive season” Lungu easiest to beat in 2021 - CK By Mirriam Chabala allow the Court of Appeal to eligible to contest the 2021 Chishimba Kambwili says determine the matter. general elections is a blessing the Constitutional Court’s In an interview, Kambwili in disguise because he is the decision to declare President said the ConCourt’s decision weakest opponent one can Edgar Lungu eligible to contest to declare President Lungu face. To page 3 the 2021 general elections is a blessing in disguise because he is the weakest opponent one can face. Murder accused tells And the embattled Roan PF member of parliament says PF Secretary General Davies Mwila should stop court he shot wife, pressurizing the Speaker of the National Assembly Patrick Former foreign a airs minister and 2021 presidential aspirant Harry Kalaba joins Matibini to declare the Roan lover in self defence an artist on stage during the Democratic Party’s fundraising dinner in Lusaka parliamentary seat vacant and Story page 3 Cops quiz Court deliberately Kay Figo Govt spent K943m on misinterpreted the over viral porn photo debt servicing in Nov, Constitution to favor By Mukosha Funga Police have warned and cautioned singer Cynthia reveals Mwanakatwe Lungu, says Chipimo Bwalya alias Kay Figo Story page 2 Story page 2 over her viral naked photo. -

La Gazette DE SAINT-SYMPH’

La Gazette DE SAINT-SYMPH’ VS SAMEDI 19 OCTOBRE - 20H00 STADE SAINT-SYMPHORIEN Édito Prochain match Infos Remonter la pente ! à Saint-Symphorien ! de la semaine Metz – Brest en Huit. C’est le nombre d’unités que Coupe de la Ligue ! compte le FC Metz après neuf journées Metz – Marseille : de championnat. Depuis, le passage de VS Réservez votre pack duo ! la victoire à trois points au sein de l’élite nationale, en 1994, c’est la deuxième fois que le dernier du classement compte SAMEDI 2 NOVEMBRE - 20H00 un total aussi élevé à ce stade de la FC METZ VS MONTPELLIER HSC compétition. Les Grenats feront leur entrée en lice à Un motif d’espoir parmi d’autres. Car, domicile en Coupe de la Ligue ! Habib Diallo DATE ET HORAIRES DÉFINITIFS jusqu’ici, le club à la Croix de Lorraine a et ses coéquipiers accueilleront le Stade prouvé à plusieurs reprises qu’il n’était Brestois 29 le mercredi 30 octobre à 21h05 au Stade Saint-Symphorien dans le cadre actuellement pas à sa place et possédait L’une des affiches les plus attendues de la des 1/16e de finale de la compétition. Les les capacités pour renouveler son bail en saison se déroulera le week-end du 13 et 14 places sont en vente au tarif unique de 8€ en Ligue 1 Conforama. Désormais, il reste à décembre, avec la venue de l’Olympique Boutique Tribunes Est et Ouest et de 13€ en Tribune confirmer ces arguments sur les différentes de Marseille à Saint-Symphorien. Réservez pelouses du championnat de France ! STADE SAINT-SYMPHORIEN Nord. -

Goalden Times: December, 2011 Edition

GOALDEN TIMES 0 December, 2011 1 GOALDEN TIMES Declaration: The views and opinions expressed in this magazine are those of the authors of the respective articles and do not necessarily reflect the official policy or position of Goalden Times. All the logos and symbols of teams are the respective trademarks of the teams and national federations. The images are the sole property of the owners. However none of the materials published here can fully or partially be used without prior written permission from Goalden Times. If anyone finds any of the contents objectionable for any reasons, do reach out to us at [email protected]. We shall take necessary actions accordingly. Cover Illustration: Neena Majumdar & Srinwantu Dey Logo Design: Avik Kumar Maitra Design and Concepts: Tulika Das Website: www.goaldentimes.org Email: [email protected] Facebook: Goalden Times http://www.facebook.com/pages/GOALden-Times/160385524032953 Twitter: http://twitter.com/#!/goaldentimes December, 2011 GOALDEN TIMES 2 GT December 2011 Team P.S. Special Thanks to Tulika Das for her contribution in the Compile&Publish Process December, 2011 3 GOALDEN TIMES | Edition V | First Whistle …………5 Goalden Times is all set for the New Year Euro 2012 Group Preview …………7 Building up towards EURO 2012 in Poland-Ukraine, we review one group at a time, starting with Group A. Is the easiest group really 'easy'? ‘Glory’ – We, the Hunters …………18 The internet-based football forums treat them as pests. But does a glory hunter really have anything to be ashamed of? Hengul -

Consulter Les Lots

COUTAU-BÉGARIE & ASSOCIÉS OVV COUTAU-BÉGARIE - AGRÉMENT 2002-113 OLIVIER COUTAU-BÉGARIE, ALEXANDRE DE LA FOREST DIvoNNE, commISSAIRES-PRISEURS ASSocIÉS. 60, AVENUE DE LA BOURDONNAIS - 75007 PARIS TEL. : 01 45 56 12 20 - FAX : 01 45 56 14 40 - WWW.coUTAUBEGARIE.com VENTE AU PROFIT DE L’ASSOCIATION LE COLLECTIF MON CARTABLE CONNECTÉ S AMEDI 14 D ÉCEMBRE 2019 V ENTE À 19 H 00, DE S LOT S 1 À 191 PARIS - HÔTEL DROUOT - SALLE 9 9, rue Drouot - 75009 Paris Tél. de la salle : +33 (0)1 48 00 20 09 EXPOSITION PUBLIQUE Samedi 14 décembre 2019 - de 11h00 à 18h00 ORDRES D’ACHAT [email protected] Fax : +33 (0)1 45 56 14 40 24h avant la vente EXPERT Jean-Marc LEYNET +33 (0)6 08 51 74 53 [email protected] RESPONSABLE DE VENTE Pierre MINIUSSI +33 (0)1 45 56 14 40 COUTAUBEGARIE.COM Toutes les illustrations de cette vente Suivez la vente en direct sont visibles sur notre site : www.coutaubegarie.com et enchérissez sur : www.drouotlive.com Un match pour la vie Les rêves d’enfant sont souvent peuplés de sportifs. Et les sportifs quels qu’ils soient, quelles qu’elles soient, ne l’oublient jamais. Avant un match ou en croisant un sourire émerveillé au moment des autographes. Tout sportif s’arrête pour cette petite fille, ce petit garçon. Car le sport est avant tout une enfance conservée, une enfance retrouvée. Cette vente doit beaucoup à leur générosité. Richard Gasquet, Jimmy Adjovi Boco, Roger Federer, Céline Dumerc, Olivier Echouafni, Corinne Diacre, Joël Muller, Sébastien Vahaamahina, Didier Deschamps et nos Bleus champions du monde de football, Eugenie Le Sommer, Philippe Hinschberger, Regis Brouard, Alain Cayzac, Nathalie Boy de la Tour, Said Chabane et tant d’autres dont vous retrouverez les tenues et dons dans ce catalogue qui conjugue altruisme et solidarité. -

Racism and Anti-Racism in Football

Racism and Anti-Racism in Football Jon Garland and Michael Rowe Racism and Anti-Racism in Football Also by Jon Garland THE FUTURE OF FOOTBALL: Challenges for the Twenty-First Century (co-editor with D. Malcolm and Michael Rowe) Also by Michael Rowe THE FUTURE OF FOOTBALL: Challenges for the Twenty-First Century (co-editor with Jon Garland and D. Malcolm) THE RACIALISATION OF DISORDER IN TWENTIETH CENTURY BRITAIN Racism and Anti-Racism in Football Jon Garland Research Fellow University of Leicester and Michael Rowe Lecturer in Policing University of Leicester © Jon Garland and Michael Rowe 2001 All rights reserved. No reproduction, copy or transmission of this publication may be made without written permission. No paragraph of this publication may be reproduced, copied or transmitted save with written permission or in accordance with the provisions of the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988, or under the terms of any licence permitting limited copying issued by the Copyright Licensing Agency, 90 Tottenham Court Road, London W1P 0LP. Any person who does any unauthorised act in relation to this publication may be liable to criminal prosecution and civil claims for damages. The authors have asserted their rights to be identified as the authors of this work in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988. First published 2001 by PALGRAVE Houndmills, Basingstoke, Hampshire RG21 6XS and 175 Fifth Avenue, New York, N. Y. 10010 Companies and representatives throughout the world PALGRAVE is the new global academic imprint of St. Martin’s Press LLC Scholarly and Reference Division and Palgrave Publishers Ltd (formerly Macmillan Press Ltd). -

Here Is No Shortage of Dangerous-Looking Designated Hosts Morocco Were So Concerned That They Teams in the Competition

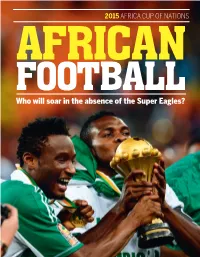

2015 AFRICA CUP OF NATIONS AFRICAN FOOT BALL Who will soar in the absence of the Super Eagles? NA0115.indb 81 13/12/2014 08:32 Edited and compiled by Colin Udoh Fears, tears and cheers n previous years, club versus country disputes have Ebebiyín might be even more troubling. It is even tended to dominate the headlines in the run-up to more remote than Mongomo, and does not seem to Africa Cup of Nations tournaments. The stories are have an airport nearby. The venue meanwhile can hold typically of European clubs, unhappy about losing just 5,000 spectators, a fraction of the 35,000 that the their African talent for two to three weeks in the national stadium in Bata can accommodate. middle of the season, pulling out all the stops in a Teams hoping to win the AFCON title will have to Ibid to hold on to their players. negotiate far more than just some transport problems. This time, however, the controversy centred on a much After all, although Nigeria and Egypt surprisingly failed more serious issue: Ebola. Whether rightly or wrongly, the to qualify, there is no shortage of dangerous-looking designated hosts Morocco were so concerned that they teams in the competition. The embarrassment of talent requested a postponement, then withdrew outright when enjoyed by the likes of Côte d’Ivoire, Ghana and Algeria the Confederation of African Football (CAF) turned will fill their opponents with fear, while so many of the down their request. teams once considered Africa’s minnows have grown in That is the reason Equatorial Guinea, who had been stature and quality in recent years. -

Sibiti À L'heure Des Grands Chantiers

L’ACTUALITÉAUQUOTIDIEN 200 FCFA www.lesdepechesdebrazzaville.com N°1911 MARDI 14 JANVIER 2014 Municipalisation accélérée Sibiti à l’heure des grands chantiers Le ministre Thierry Moungala et Edgard N’Guesso lors de la visite des chantiers À la faveur de la municipalisa- tiers avancent à pas de géant roulera le défilé civil et militaire teur du domaine présidentiel, pour que nous n’ayons pas à tion accélérée et de la célébra- dans le chef-lieu du départe- ont été, entre autres, visités sa- Edgar N’Guesso. Le ministre courir au dernier moment tion du 54e anniversaire de l’in- ment de la Lékoumou. L’aéro- medi par une délégation s’est dit satisfait de constater avec tout le stress lié à la pré- dépendance du Congo, en août port, le palais présidentiel, la conduite par le ministre « que les travaux ont com- cipitation ». prochain, de nombreux chan- place de la Concorde où se dé- Thierry Moungalla et le direc- mencé suffisamment à temps, Page 3 CHAN GESTION FORESTIÈRE Sortie manquée pour les Diables rouges Plus de 6 milliards FCFA Les Diables rouges, logés dans le groupe C, ont manqué leur première de taxes recouvrées en 2013 sortie au championnat d’Afrique des nations de football qui se joue en Le ministère de velles dispositions prises Afrique du sud, en s’inclinant un but l’Économie fores- par le Congo en matière à zéro face aux Blacks Stars du tière et du dévelop- d’exportation de bois. Ghana. pement durable a « Dans le cadre du respect Les Congolais qui retrouvent la com- enregistré, courant du quota des bois autorisé pétition de haut niveau, quatorze ans 2013, un gain de à l’exportation, une opé- après la CAN 2000, n’ont pas démé- rité face à une formation ghanéenne 6.662.408.735 FCFA ration de blocage des vo- mieux outillée et finaliste de la pre- issu des recouvre- lumes dépassant ledit mière édition, en 2009. -

Africa Cup of Nations 2013 Media Guide

Africa Cup of Nations 2013 Media Guide 1 Index The Mascot and the Ball ................................................................................................................ 3 Stadiums ........................................................................................................................................ 4 Is South Africa Ready? ................................................................................................................... 6 History ........................................................................................................................................... 9 Top Scorers .................................................................................................................................. 12 General Statistics ......................................................................................................................... 14 Groups ......................................................................................................................................... 16 South Africa ................................................................................................................................. 17 Angola ......................................................................................................................................... 22 Morocco ...................................................................................................................................... 28 Cape Verde ................................................................................................................................. -

PAT WELTON INTERVIEW ^EJ Fk^F Top Nostalgia" Buffs" "Arthur Godfrey and Dave Knight Take a Wander Down Memory Lane and Have a Few Pints With' Pat Welton

"N%? . Wl &• 's': PAT WELTON INTERVIEW ^EJ fK^f Top nostalgia" buffs" "Arthur Godfrey and Dave Knight take a wander down memory lane and have a few pints with' Pat Welton. Pat Welton joined the club as a goal- As Pat had a lot of family and frien- keeper in 1947. He had just come out ds up there, Alex Stock gave him spe- of the army and wasn't sure of what cial permisssion to stay behind and to do. His brother had been in the come back on the train. Pat didn t army with Arthur Banner (O's skipper think, there would be many 0's fans I at the time) and they arranged a tri- at Euston. But he couldn t have been al for Pat. He had his trial on a more wrong, and as soon as the fans I Tuesday and he played for the 0's on saw him he was carried shoulder high the Saturday. in triumph. Things may have worked out differ- ent because'1 during his army time Pat played basketball as well as football. • He had considered trying for a place in the British Olympic team, but opt- ed for football. Eventually he was signed as a pro- fessional so his wages were £7.00 during the season and £5.00 in the summer. He made his debut at Notts County in October 1949, where he cou- Idn't have had a more dramatic intro- duction to league football, the Magp- ies winning 7-1. The first thing he learnt was how to pick the ball out of the net. -

25 April 1987 Opposition: Everton Competition: League

March March 1987 2 5 Times Sunday Times Date: 25 April 1987 April1987 Opposition: Everton Competition: League Rush enters the gallery of legends with his sure-shot finishing Rush skill wins fierce classic Liverpool ........... 3 Everton ............. 1 Liverpool ....... 3 Everton ......... 1 The 136th Merseyside derby will feature in conversations for years to come and IAN RUSH, equalling the derby-goals, record of Dixie Dean, claimed not only will be recalled as more than a glittering jewel of a match. Like a sepia photograph history but the winners' spoils in a performance which means the championship is curled at the edges with nostalgia, it will provoke the memory of a significant not quite dead. But Everton, having lost the battle, should still win the war. moment in history. Watched by 44,827 in the stadium and by more than 40 nations via television Those who witnessed Saturday's event (Anfield was filled to capacity and outside the UK, the soul of English football, and of this city, was laid bare. The thousands were locked outside) will talk about the lean, dark-haired figure whose passion comes from the people who, despite the unemployment of one in four, final contribution to the local dispute earned him the right to be considered a still produce pounds 2m for wage bills per club per season to ensure Merseyside is legend. They may never see the like of Ian Rush again. a cut above the rest. This without doubt is the pulse of the English game: too fast His name, which echoed thunderously around the stadium throughout the closing to last, too fast for subtleties, but where in the world would you match the five minutes, is destined to be whispered on those same terraces for as long as physical spectacle, the unrelenting effort? For 25 years Merseyside has so the game is played there. -

Can I Kick It? Unit 4 How Money Took Over1 Football…

Unit 4 Can I Kick It? How Money Took over1 Football… in 1879 No turnstiles2, no tickets, no huge wage demands. Late 19th-century football was a serene place… until money came along and turned it into the monster we love and loathe3 today. The first recorded outbreak of ‘professionalism’ occurred in Lancashire when Darwen employed two Scots, Fergie Suter and James Love, in 1879. Though it caused a minor scandal, players had been secretly paid – in cash, fish, beer, whatever – for years. In 1885, professionalism was legalised and in 1901 a £4-a-week wage limit introduced. The Football Association (FA) tried to cling4 to amateur ideals, but in 1905 Middlesbrough broke the bank5, buying Sunderland’s Alf Common for a record £1,000. Boro had been languishing6 near the relegation places in Division One, but with Common on board, they leapt7 up to mid-table anonymity and languished there for a bit. By 1922 the maximum wage had grown to £8 a week (£6 in the summer), and clubs also gave a loyalty bonus of £650 after five years. The money no longer came from the club owners either – since Small Heath (Birmingham City) set the trend in 1888, clubs had been turning themselves into limited companies and directors saw football as a money-spinning8 pension plan. The first £10,000 transfer came in 1928 when Arsenal bought David Jack from Bolton (none of the money going to the player or his agent), but by the time Jimmy Guthrie took over as chairman of the Players’ Union in 1947, the maximum wage was still only £12 a week (£10 in the summer). -

Krajowy Punkt Informacyjny Ds. Imprez Sportowych 2021-09-26, 00:21

KRAJOWY PUNKT INFORMACYJNY DS. IMPREZ SPORTOWYCH http://www.kpk.policja.gov.pl/kpk/aktualnosci/1328,Zambia-lepsza-od-Wybrzeza-Kosci-Sloniowej.html 2021-09-26, 00:21 Strona znajduje się w archiwum. ZAMBIA LEPSZA OD WYBRZEŻA KOŚCI SŁONIOWEJ Reprezentacja Zambii po raz pierwszy w historii sięgnęła Puchar Narodów Afryki, w finale pokonując Wybrzeże Kości Słoniowej. Regulaminowy czas gry i dogrywka nie przyniosły goli, a o zwycięstwie zdecydował konkurs rzutów karnych. W regulaminowym czasie gry na prowadzenie WKS mógł wyprowadzić Didier Drogba, ale nie wykorzystał rzutu karnego. Mecz mógł rozpocząć się znakomicie dla piłkarzy Zambii. Po sprytnie rozegranym rzucie rożnym piłka trafiła do Sinkali, który mimo interwencji trzech obrońców "Słoni" oddał celny strzał. Dobrym refleksem wykazał się bramkarz Boubacar Barry, który obronił to uderzenie. W piątej minucie kontuzji doznał Joseph Musonda. Zastąpił go Mulenga. W 14. minucie strzał głową oddał Mayuka. Piłka wylądowała na siatce. W 30. minucie zespołowa akcja WKS. W polu karnym Didier Drogba odegrał do Yaya Toure, a ten minimalnie przestrzelił. Piłka minęła prawy słupek bramki Mweene'a. W 37. minucie bardzo ładną akcję przeprowadził Katongo, który ograł Zokorę. Nikt jednak nie doszedł do jego dośrodkowania. W drugiej części gry walka toczyła się głównie w środkowej strefie boiska. Defensywa Wybrzeża Kości Słoniowej dobrze spisywała się przy rzutach rożnych wykonywanych przez rywali. Senegalski sędzia Badara Diatta nie karał zawodników kartkami. Aż do 63. minuty. Wtedy ukarany został Tiote. Trzy minuty później "żółtko" zobaczył inny reprezentant WKS Babmba. W 69. minucie Mulenga sfaulował w polu karnym Gervinho i również został ukarany kartką. Do piłki ustawionej na 11 metrze podszedł Didier Drogba.