A Notable Pennsylvanian: Ida Minerva Tarbell, 1857-1944 Josephine D

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Ida M. Tarbell and the Rise of Documentary Evidence

UNIVERSITY-WIDE RESEARCH GRANTS FOR LIBRARIANS COVER SHEET NOTE: Grant proposals are confidential until funding decisions are made. INSTRUCTIONS: The applicant(s) must submit two (2) copies of their application packet. The application packet consists of the Cover Sheet and the Proposal. Applicants send 1 (one) printed copy of their application packet, with signatures, to the Chair of the divisional research committee, who forwards the packet to the Chair of the university-wide Research and Professional Development Committee. Applicants send the second copy of their application packet as an email attachment to the Chair of the divisional research committee who forwards it on to the Chair of the university-wide Research and Professional Development Committee. Date of Application: 12 January, 2011 Title of Proposal/Project: “Prepared Entirely From Documents and Contemporaneous Records”: Ida M. Tarbell and the Rise of Documentary Evidence in Journalism Expected Length of Project : 1 week for the archival research, 5 months to finish paper Total Funds Requested from LAUC University-Wide Research Funds: $1,924 Primary Applicant Your Name (include your signature on the paper copy): Dawn Schmitz Academic Rank and Working Title: Associate Librarian III, Archivist Bargaining Unit Member/Non-Member: Member Campus Surface Mail Address: P.O. Box 19557 Irvine, CA 92623-9557 Zot Code: 8100 Telephone and Email Address: 949-824-4935, [email protected] URL for home campus directory (will be used for link on LAUC University-Wide Funded Research Grants web page): http://directory.uci.edu/ Co-Applicant(s) 1 Name: Academic Rank and Working Title: Bargaining Unit Member/Non-Member: Campus Surface Mail Address: Telephone and Email Address: Proposal Abstract (not to exceed 250 words): This proposal is for funding to complete archival research for a paper that explores the early development of the use of public and corporate records in American investigative reporting. -

Clara E. Sipprell Papers

Clara E. Sipprell Papers An inventory of her papers at Syracuse University Finding aid created by: - Date: unknown Revision history: Jan 1984 additions, revised (ASD) 14 Oct 2006 converted to EAD (AMCon) Feb 2009 updated, reorganized (BMG) May 2009 updated 87-101 (MRC) 21 Sep 2017 updated after negative integration (SM) 9 May 2019 added unidentified and "House in Thetford, Vermont" (KD) extensively updated following NEDCC rehousing; Christensen 14 May 2021 correspondence added (MRC) Overview of the Collection Creator: Sipprell, Clara E. (Clara Estelle), 1885-1975. Title: Clara E. Sipprell Papers Dates: 1915-1970 Quantity: 93 linear ft. Abstract: Papers of the American photographer. Original photographs, arranged as character studies, landscapes, portraits, and still life studies. Correspondence (1929-1970), clippings, interviews, photographs of her. Portraits of Louis Adamic, Svetlana Allilueva, Van Wyck Brooks, Pearl S. Buck, Rudolf Bultmann, Charles E. Burchfield, Fyodor Chaliapin, Ralph Adams Cram, W.E.B. Du Bois, Albert Einstein, Dorothy Canfield Fisher, Ralph E. Flanders, Michel Fokine, Robert Frost, Eva Hansl, Roy Harris, Granville Hicks, Malvina Hoffman, Langston Hughes, Robinson Jeffers, Louis Krasner, Serge Koussevitzky, Luigi Lucioni, Emil Ludwig, Edwin Markham, Isamu Noguchi, Maxfield Parrish, Sergei Rachmaninoff, Eleanor Roosevelt, Dane Rudhyar, Ruth St. Denis, Otis Skinner, Ida Tarbell, Howard Thurman, Ridgely Torrence, Hendrik Van Loon, and others Language: English Repository: Special Collections Research Center, Syracuse University Libraries 222 Waverly Avenue Syracuse, NY 13244-2010 http://scrc.syr.edu Biographical History Clara E. Sipprell (1885-1975) was a Canadian-American photographer known for her landscapes and portraits of famous actors, artists, writers and scientists. Sipprell was born in Ontario, Canada, a posthumous child with five brothers. -

Not for Publication:__ Vicinity

NATIONAL HISTORIC LANDMARK NOMINATION NFS Form 10-900USDI/NPS NRHP Registration Form (Rev. 8-86) OMB No. 1024-0018 IDA TARBELL HOUSE Page 1 United States Department of the Interior, National Park Service National Register of Historic Places Registrauon Form 1. NAME OF PROPERTY Historic Name: Ida Tarbell House Other Name/Site Number: 2. LOCATION Street & Number: 320 Valley Road Not for publication:__ . City/Town: Easton Vicinity:__ State: CT County: Fairfield Code: 001 Zip Code: 06612 3. CLASSIFICATION Ownership of Property Category of Property Private: X Building(s): X Public-local:__ District:__ Public-State:__ Site:__ Public-Federal: Structure:__ Object:__ Number of Resources within Property Contributing Noncontributing 4 1 buildings ____ sites 1 structures ____ objects 2 Total Number of Contributing Resources Previously Listed in the National Register: 0 Name of related multiple property listing: N/A NFS Form 10-900USDI/NPS NRHP Registration Form (Rev. 8-86) OMB No. 1024-0018 IDA TARBELL HOUSE Page 2 United States Department of the Interior, National Park Service National Register of Historic Places Registration Form 4. STATE/FEDERAL AGENCY CERTIFICATION As the designated authority under the National Historic Preservation Act of 1986, as amended, I hereby certify that this ___ nomination ___ request for determination of eligibility meets the documentation standards for registering properties in the National Register of Historic Places and meets the procedural and professional requirements set forth in 36 CFR Part 60. In my opinion, the property ___ meets ___ does not meet the National Register Criteria. Signature of Certifying Official Date State or Federal Agency and Bureau In my opinion, the property ___ meets ___ does not meet the National Register criteria. -

Historical Magazine Volume 39 Winter, 1956 Number 4

The Westren Pennsylvania Historical Magazine Volume 39 Winter, 1956 Number 4 IDA TARBELL'S SECOND LOOK AT STANDARD OIL IDA M. TARBELL Edited by Ernest C.Miller* Minerva Tarbell was a remarkable woman who lived an active Idaand productive life during one of the most amazing periods of Ameri- can business development. As the second of those writers known as /he "muckrakers," 1 she was, in the eyes of early oildom, the most accurate and responsible of them all,and is best remembered today for her monumental work, The History of the Standard Oil Company. 2 Certain it is that of the early writers who wrote either for or against Standard Oil,none was so well equipped to do the job as was Ida Tarbell Miss Tarbell was born in a logcabin in Erie County, Pennsylvania, * Ernest C. Miller of Warren, Pennsylvania, has been an oil man all his life and is today vice-president of the West Perm Oil Company Inc., and of the West Penn Oil Company (Canada) Ltd. He is the author of three oil books and many pamphlets pertaining to early oildays. InVolume 31 of the Western Pennsylvania Historical Magazine Mr. Miller was the author of "John Wilkes Booth in the Pennsylvania Oil Region" and "Early Maps of the Pennsylvania Oil Fields." —Ed. 1 The first is generally assumed to De Henry Demarest Lloyd whose article "The Story of a Great Monopoly," appeared in the Atlantic Monthly, March, 1881, pp 317-334. Bunyan's Pilgrim's Progress provided the name "muckraker." Inthis work, the Man with the Muckrake was more occupied with raking filth than with future happiness. -

Biography Activity: Ida Tarbell

NAME _______________________________________________ CLASS ___________________ DATE _________________ BIOGRAPHY Ida Tarbell Among the muckrakers of the Progressive Era, none surpassed the careful reporting, clever pen, and moral outrage of Ida Tarbell. She took on the nation’s most powerful trust—Standard Oil—and its creator—the nation’s wealthiest man, John D. Rockefeller—in 18 installments of McClure’s magazine. As you read, think about how Ida Tarbell’s writing influenced her country’s history. Ida Tarbell developed her moral outrage at the and her experience with Standard Oil, McClure Standard Oil trust through personal family expe- assigned her to the story. Her father, recalling the rience. Soon after her birth in 1857 on a farm in trust’s ruthless tactics, pleaded, “Don’t do it, Ida.” Pennsylvania, oil was discovered in nearby Titus- Others also tried to warn her away from the trust’s ville. Her father, Franklin, saw an opportunity to “all-seeing eye and the all-powerful reach,” pre- make money in this promising new field. He became dicting, “they’ll get you in the end,” but Tarbell the first manufacturer of wooden tanks for the oil would not be stopped. For the next two years, she industry and established a prosperous business. researched the business practices of Standard Oil In time, however, the Standard Oil Company and then began writing her series. In the first began to force other oil suppliers out of business. installment, she described the hope, confidence, Standard Oil became Franklin’s only client, and and energy of pioneer oil men. “But suddenly, at refused to pay his prices. -

Chapter 18 Video, “The Stockyard Jungle,” Portrays the Horrors of the Meatpacking Industry First Investigated by Upton Sinclair

The Progressive Movement 1890–1919 Why It Matters Industrialization changed American society. Cities were crowded with new immigrants, working conditions were often bad, and the old political system was breaking down. These conditions gave rise to the Progressive movement. Progressives campaigned for both political and social reforms for more than two decades and enjoyed significant successes at the local, state, and national levels. The Impact Today Many Progressive-era changes are still alive in the United States today. • Political parties hold direct primaries to nominate candidates for office. • The Seventeenth Amendment calls for the direct election of senators. • Federal regulation of food and drugs began in this period. The American Vision Video The Chapter 18 video, “The Stockyard Jungle,” portrays the horrors of the meatpacking industry first investigated by Upton Sinclair. 1889 • Hull House 1902 • Maryland workers’ 1904 opens in 1890 • Ida Tarbell’s History of Chicago compensation laws • Jacob Riis’s How passed the Standard Oil the Other Half Company published ▲ Lives published B. Harrison Cleveland McKinley T. Roosevelt 1889–1893 ▲ 1893–1897 1897–1901 1901–1909 ▲ ▲ 1890 1900 ▼ ▼ ▼▼ 1884 1900 • Toynbee Hall, first settlement • Freud’s Interpretation 1902 house, established in London of Dreams published • Anglo-Japanese alliance formed 1903 • Russian Bolshevik Party established by Lenin 544 Women marching for the vote in New York City, 1912 1905 • Industrial Workers of the World founded 1913 1906 1910 • Seventeenth 1920 • Pure Food and • Mann-Elkins Amendment • Nineteenth Amendment Drug Act passed Act passed ratified ratified, guaranteeing women’s voting rights ▲ HISTORY Taft Wilson ▲ ▲ 1909–1913 ▲▲1913–1921 Chapter Overview Visit the American Vision 1910 1920 Web site at tav.glencoe.com and click on Chapter ▼ ▼ ▼ Overviews—Chapter 18 to preview chapter information. -

Press Conference at the National Women's Hall of Fame of Hon

10-07-00: PRESS CONFERENCE AT THE NATIONAL WOMEN'S HALL...NET RENO ATTORNEY GENERAL OF THE UNITED STATES NEW YORK PRESS CONFERENCE AT THE NATIONAL WOMEN'S HALL OF FAME OF HON. JANET RENO ATTORNEY GENERAL OF THE UNITED STATES Saturday, October 7, 2000 New York Chiropractic College Athletic Center 2360 State Route 89 Seneca Falls, New York 9:38 a.m. P R O C E E D I N G S CHAIR SANDRA BERNARD: Good morning and welcome to the National Women's Hall of Fame Honors Weekend and Induction Ceremony. I am Sandra Bernard, Chair of the weekend's events. Today, before a sell-out crowd, we will induct 19 remarkable women into the Hall of Fame. Now, those of you who are history buffs may know that the idea to form a Hall to honor, in perpetuity, the contributions to society of American women started, like so many other good things in Seneca Falls have, over tea. And just like the tea party that spawned the Women's Rights Convention, the concept of a National Women's Hall of Fame was an idea whose time has come. http://www.usdoj.gov/archive/ag/speeches/2000/10700agsenecafalls.htm (1 of 11) [4/20/2009 1:10:27 PM] 10-07-00: PRESS CONFERENCE AT THE NATIONAL WOMEN'S HALL...NET RENO ATTORNEY GENERAL OF THE UNITED STATES NEW YORK Our plans for the morning are to tell you a bit more about the mission, the moment and the meaning, and then to introduce you to the inductees. -

John Ahouse-Upton Sinclair Collection, 1895-2014

http://oac.cdlib.org/findaid/ark:/13030/c8cn764d No online items INVENTORY OF THE JOHN AHOUSE-UPTON SINCLAIR COLLECTION, 1895-2014, Finding aid prepared by Greg Williams California State University, Dominguez Hills Archives & Special Collections University Library, Room 5039 1000 E. Victoria Street Carson, California 90747 Phone: (310) 243-3895 URL: http://www.csudh.edu/archives/csudh/index.html ©2014 INVENTORY OF THE JOHN "Consult repository." 1 AHOUSE-UPTON SINCLAIR COLLECTION, 1895-2014, Descriptive Summary Title: John Ahouse-Upton Sinclair Collection Dates: 1895-2014 Collection Number: "Consult repository." Collector: Ahouse, John B. Extent: 12 linear feet, 400 books Repository: California State University, Dominguez Hills Archives and Special Collections Archives & Special Collection University Library, Room 5039 1000 E. Victoria Street Carson, California 90747 Phone: (310) 243-3013 URL: http://www.csudh.edu/archives/csudh/index.html Abstract: This collection consists of 400 books, 12 linear feet of archival items and resource material about Upton Sinclair collected by bibliographer John Ahouse, author of Upton Sinclair, A Descriptive Annotated Bibliography . Included are Upton Sinclair books, pamphlets, newspaper articles, publications, circular letters, manuscripts, and a few personal letters. Also included are a wide variety of subject files, scholarly or popular articles about Sinclair, videos, recordings, and manuscripts for Sinclair biographies. Included are Upton Sinclair’s A Monthly Magazine, EPIC Newspapers and the Upton Sinclair Quarterly Newsletters. Language: Collection material is primarily in English Access There are no access restrictions on this collection. Publication Rights All requests for permission to publish or quote from manuscripts must be submitted in writing to the Director of Archives and Special Collections. -

Unit 5- an Age of Reform

Unit 5- An Age of Reform Important People, Terms, and Places (know what it is and its significance) Civil service Gilded Age Primary Recall Initiative Referendum Muckraker Theodore Roosevelt Susan B Anthony Conservation William Howard Taft Jane Addams Woodrow Wilson Carrie Chapman Catt Suffragist Ida Tarbell Frances Willard Upton Sinclair Prohibition Temperance Lucretia Mott Carrie Nation Jacob Riis Booker T Washington W.E.B Dubois Robert LaFollette The Progressive Party 16th Amendment Spoils System Thomas Nast You should be able to write an essay discussing the following: 1. What were political reforms of the period that increased “direct” democracy? 2. The progressive policies of Theodore Roosevelt, William Howard Taft, and Woodrow Wilson. How did they expand the power of the federal government? 3. The role of the Muckrakers in creating change in America 4. Summarize the other reform movements of the Progressive era. 5. What was the impact of the Progressive Movement on women and blacks? 6. Compare and contrast the beliefs of Booker T. Washington and W.E.B Dubois Important Dates to Remember 1848 – Declaration of Sentiments written by Elizabeth Cady Stanton 1874 – Woman’s Christian Temperance Union formed. 1889 – Jane Addams founds Hull House 1890 – Jacob Riis publishes “How the Other Half Lives” 1895 – Anti Saloon League founded 1904 – Ida Tarbell publishes “The History of Standard Oil” 1906 – Upton Sinclair publishes “The Jungle” 1906 – Meat Inspection Act and Pure Food and Drug Act passed 1909 – National Association for the Advancement of Colored People founded. (NAACP) 1913 – 16th Amendment passed 1914 – Clayton Anti-Trust Act passed 1919 – 18th Amendment passed (prohibition) 1920 – 19th Amendment passed (women’s suffrage) . -

Vindicating Capitalism: the Real History of the Standard Oil Company

Vindicating Capitalism: The Real History of the Standard Oil Company By Alex Epstein Who were we that we should succeed where so many others failed? Of course, there was something wrong, some dark, evil mystery, or we never should have succeeded!1 —John D. Rockefeller The Standard Story of Standard Oil In 1881, The Atlantic magazine published Henry Demarest Lloyd’s essay “The Story of a Great Monopoly”—the first in- depth account of one of the most infamous stories in the history of capitalism: the “monopolization” of the oil refining market by the Standard Oil Company and its leader, John D. Rockefeller. “Very few of the forty millions of people in the United States who burn kerosene,” Lloyd wrote, know that its production, manufacture, and export, its price at home and abroad, have been controlled for years by a single corporation—the Standard Oil Company... The Standard produces only one fiftieth or sixtieth of our petroleum, but dictates the price of all, and refines nine tenths. This corporation has driven into bankruptcy, or out of business, or into union with itself, all the petroleum refineries of the country except five in New York, and a few of little consequence in Western Pennsylvania... the means by which they achieved monopoly was by conspiracy with the railroads... [Rockefeller] effected secret arrangements with the Pennsylvania, the New York Central, the Erie, and the Atlantic and Great Western... After the Standard had used the rebate to crush out the other refiners, who were its competitors in the purchase of petroleum at the wells, it became the only buyer, and dictated the price. -

Suffrage Organizations Chart.Indd

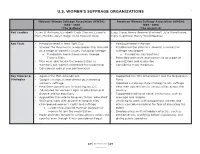

U.S. WOMEN’S SUFFRAGE ORGANIZATIONS 1 National Woman Suffrage Association (NWSA), American Woman Suffrage Association (AWSA), 1869 - 1890 1869 - 1890 “The National” “The American” Key Leaders Susan B. Anthony, Elizabeth Cady Stanton, Lucretia Lucy Stone, Henry Browne Blackwell, Julia Ward Howe, Mott, Matilda Joslyn Gage, Anna Howard Shaw Mary Livermore, Henry Ward Beecher Key Facts • Headquartered in New York City • Headquartered in Boston • Started The Revolution, a newspaper that focused • Established the Woman’s Journal, a successful on a range of women’s issues, including suffrage suffrage newspaper o Funded by a pro-slavery man, George o Funded by subscriptions Francis Train • Permitted both men and women to be a part of • Men were able to join the organization as organization and leadership members but women controlled the leadership • Considered more moderate • Considered radical and controversial Key Stances & • Against the 15th Amendment • Supported the 15th Amendment and the Republican Strategies • Sought a national amendment guaranteeing Party women’s suffrage • Adopted a state-by-state strategy to win suffrage • Held their conventions in Washington, D.C • Held their conventions in various cities across the • Advocated for women’s right to education and country divorce and for equal pay • Supported traditional social institutions, such as • Argued for the vote to be given to the “educated” marriage and religion • Willing to work with anyone as long as they • Unwilling to work with polygamous women and championed women’s rights and suffrage others considered radical, for fear of alienating the o Leadership allowed Mormon polygamist public women to join the organization • Employed less militant lobbying tactics, such as • Made attempts to vote in various places across the petition drives, testifying before legislatures, and country even though it was considered illegal giving public speeches © Better Days 2020 U.S. -

IDA M. TARBELL: the HISTORIAN a Master's Thesis by ONUR DĐZDAR

IDA M. TARBELL: THE HISTORIAN A Master’s Thesis by ONUR DĐZDAR Department of History Bilkent University Ankara September 2010 To My Family .. IDA M. TARBELL: THE HISTORIAN The Institute of Economics and Social Sciences of Bilkent University by ONUR DĐZDAR In Partial Fulfilment of the Requirements for the Degree of MASTER OF ARTS in THE DEPARTMENT OF HISTORY BILKENT UNIVERSITY ANKARA September 2010 I certify that I have read this thesis and have found that it is fully adequate, in scope and in quality, as a thesis for the degree of Master of Arts in History. Assist. Prof. Edward Kohn Supervisor I certify that I have read this thesis and have found that it is fully adequate, in scope and in quality, as a thesis for the degree of Master of Arts in History. Assist. Prof. Paul Latimer Examining Committee Member I certify that I have read this thesis and have found that it is fully adequate, in scope and in quality, as a thesis for the degree of Master of Arts in History. Assist. Prof. Dennis Bryson Examining Committee Member Approval of the Institute of Economics and Social Sciences Prof. Dr. Erdal Erel Director ABSTRACT IDA M. TARBELL: THE HISTORIAN Dizdar, Onur M.A., Department of History Supervisor: Assist. Prof Edward Kohn September 2010 This thesis focuses on Ida M. Tarbell, one of the most influential literary figures of the late 19th and early 20th century in the United States. She has been recognized as the pioneer of investigative journalism and generally referred to as a muckraker. This study, however, will argue that she was primarily a historian.