An Analysis of Fostering Intercultural Competence Among Host Communities in Hostels (Case Study: Hi Santa Monica)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Guidelines on Tour Operators and Travel Agents Licences

GUIDELINES ON TOUR OPERATORS AND TRAVEL AGENTS LICENCES TRANSPORT (TOUR OPERATORS AND TRAVEL AGENTS) ACT, 1982 AS AMENDED BY THE PACKAGE HOLIDAY AND TRAVEL TRADE ACT, 1995 These Guidelines are intended to be of practical assistance to licence applicants and members of the industry and do not purport to be a legal interpretation of the relevant legislation. Any further information required in connection with the Act or related Regulations may be obtained from: Commission for Aviation Regulation 3rd Floor, Alexandra House Earlsfort Terrace Dublin 2 Opening Hours: Monday – Friday 10 a.m. – 5 p.m. Lunch 1 - 2 p.m. Tel: +353 1 6611700 Fax: +353 1 6612092 E-mail: [email protected] 1 TABLE OF CONTENTS 1. INTRODUCTION ..................................................................................................................4 2. DEFINITIONS OF TOUR OPERATOR AND TRAVEL AGENT ....................................................7 3. TOUR OPERATORS LICENCE................................................................................................8 4. TRAVEL AGENTS LICENCE ...................................................................................................9 5. APPLYING FOR A LICENCE ................................................................................................10 6. DURATION OF LICENCES ..................................................................................................11 7. LICENCE FEES ...................................................................................................................12 -

21 Functions of Travel Agencies and Tour

Functions of Travel Agencies and Tour Operations MODULE – 6A Travel and Tour Operation Bussiness 21 FUNCTIONS OF TRAVEL Notes AGENCIES AND TOUR OPERA- TIONS Travel agents and tour operators play a major role in boosting tourism growth across the globe. They are today accepted as crucial component of travel and tourism industry. They contribute to revenue generation through travel trade operations by bringing together clients and suppliers. According to an estimate, they account for 70% of domestic and 90% of international tourists traffic globally. In this chapter we will discuss the major functions of travel agencies and tour operators such as marketing and publicity, booking of tickets, itinerary preparation, designing of tour packages, processing of travel documents, travel insurance, travel research, conducting tours etc. OBJECTIVES After studying this lesson, you will be able to: z explain the importance of Marketing and Publicity; z explain the functioning of the following, Reservation of Tickets, Reservation of Hotel Rooms, Reservation of Ground Services, Selling Cruise Package; z conduct research, training and development of marketing of tourism; z analyse the relevance of Corporate Social Responsibility; z design Package Tours; z conduct FIT, GIT and FAM Tours; TOURISM 13 MODULE – 6A Functions of Travel Agencies and Tour Operations Travel and Tour Operation Bussiness z to provide Travel Information; z coordinate with Public and Private Tour Organisations and z appreciate the role of Disaster Preparedness 21.1 MARKETING AND PUBLICITY Marketing and publicity of tourism products in general and tour packages and Notes other services in specific is one of the major functions of travel agencies and tour operators. -

Republic of the Philippines Department of Tourism Manila

REPUBLIC OF THE PHILIPPINES DEPARTMENT OF TOURISM MANILA RULES AND REGULATIONS TO GOVERN THE ACCREDITATION OF TRAVEL AND TOUR SERVICES PURSUANT TO THE PROVISIONS OF EXECUTIVE ORDER NO.120 IN RELATION TO REPUBLIC ACT NO.7160, OTHERWISE KNOWN AS THE LOCAL GOVERNMENT CODE OF 1991 ON THE DEVOLUTION OF THE LICENSING AND REGULATORY AUTHORITY OVER CERTAIN ESTABLISHMENTS, THE FOLLOWING RULES AND REGULATIONS TO GOVERN THE ACCREDITATION OF TOUR OPERATORS, TOURIST TRANSPORTOPERA TORS, TOUR GUIDES AND PROFESSIONAL CONGRESS ORGANIZERS ARE HEREBY PROMULGATED . CHAPTER I DEFINITION Section 1. Definition of Terms. For purposes of these Rules, the following shall mean: a. "Tour Operator" shall mean an entity which may either be a single proprietorship, partnership or corporation regularly engaged in the business of extending to individuals or groups, such services pertaining to arrangements and bookings for transportation and/or accommodation, handling and/or conduct of inbound tours whether or not for a fee, commission, or any form of compensation; b. "Inbound Tour" means a tour to or of the Philippines or any place within the Philippines; c. "Department" shall mean the Department of Tourism; d. "Accreditation" a certification issued by the Department that the holder is recognized by the Department as having complied with its minimum standards in the operation of the establishment concerned; e. "Tour Guide" shall mean an individual who guides tourists, both foreign and domestic, for a fee, commission, or any other form of lawful remuneration. f. "Tourist Land Transport Operator" - a person or entity which may either be a single proprietorship, partnership or corporation, regularly engaged in providing, for a fee or lawful consideration, tourist transport services as hereinafter defined, either on charter or regular run. -

Amsterdam, 21 January 2009

Amsterdam, 17 October 2013 Announcement of partnership with Hostelling International Dear ISIC issuers, We are very pleased to announce that a global Memorandum of Understanding (MoU) has been signed between the International Student Identity Card (ISIC) Association and Hostelling International (HI). In fact, this MoU is the renewal of our partnership dating back to 1993. The objective of this MoU between the ISIC Association and Hostelling International is to outline joint opportunities for areas to work together on a local level, and to introduce a cobranded HI-ISIC card as a possible Hostelling International membership card where appropriate locally. Through the contact list attached to the MoU, we encourage you to connect with Hostelling International on a country level in order to explore the potential relationship and/or co-brand opportunities. Hostelling International will today also be announcing the partnership with the ISIC Association to their local member organisations. About Hostelling International Hostelling International is a non-governmental, not-for-profit organisation representing 70 Member Associations and Associate Organisations all over the world. Hostelling International works closely with the United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organisation (UNESCO) and the World Tourism Organisation (UNWTO). Hostelling International has also been identified as the sixth largest provider of travel accommodation in the world. Membership With nearly four million guest members, HI is one of the world’s largest youth membership organisations and is the only global network of Youth Hostel Associations. Customers can choose from around 3,700 Youth Hostels, all meeting internationally agreed standards in order to guarantee guest a safe and friendly place to stay. -

Travel Leaders Echo Experts: Make Fact-Based Decisions About Traveling U.S

Travel Leaders Echo Experts: Make Fact-Based Decisions About Traveling U.S. Officials: "It Is Safe for Healthy Americans to Travel" WASHINGTON (March 10, 2020)—A coalition of 150 travel-related organizations issued the following statement on the latest developments around coronavirus (signatories below): "For the travel and hospitality industry, the safety of the traveling public, our guests and our employees is of the utmost importance. We are in daily contact with public health authorities and are acting on the most up-to-date information on the evolving coronavirus situation. "Health and government officials have continually assured the public that healthy Americans can 'confidently travel in this country.' While it's critically important to remain vigilant and take useful precautions in times like these, it's equally important to make calm, rational, and fact- based decisions. "Though the headlines may be worrisome, experts continue to say the overall coronavirus risk in the U.S. remains low. At-risk groups are older individuals and those with underlying health conditions, who should take extra precautions. "The latest expert guidance indicates that for the overwhelming majority, it's OK to live, work, play and travel in the U.S. By seeking and heeding the latest expert guidance—which includes vigorous use of good health practices, similar to the preventive steps recommended for the seasonal flu—America's communities will stay strong and continue to thrive. The decision to cancel travel and events has a trickle-down effect that threatens to harm the U.S. economy, from locally owned hotels, restaurants, travel advisors and tour operators to the service and frontline employees who make up the backbone of the travel industry and the American economy. -

Working with Otas

WORKING WITH OTAS How to Drive More Bookings, Make More Money and Not Lose Your Shirt HOLLIS THOMASES AUGUST 2018 +1 720.410.9395 www.arival.travel Boulder, CO [email protected] WHY YOU SHOULD READ THIS Over the past two decades, online travel agencies, or OTAs (companies such as Expedia, Priceline, TripAdvisor Experiences and Booking.com that sell travel online), have redefined how travelers book flights and hotels. Now they are going big into tours, activities and attractions. We have done the hard work of surveying and interviewing OTAs, tour and activity operators and industry experts to prepare this Arival Guide to Working with OTAs. Our goal: to help you succeed amid the growing and complex world of online activity sellers. ABOUT ARIVAL Arival advances the business of creating awesome in-destination experiences through events, insights and community for Tour, Activity & Attraction providers. Our mission: establish the Best Part of Travel as the major sector of the global travel, tourism and hospitality industry that it deserves to be. Page 2 Copyright 2018 Arival LLC All Rights Reserved www.arival.travel TABLE OF CONTENTS Online Travel Agencies: An Introduction 4 - What’s an OTA, and Why You Should Care - Where Should You Start? - What Tour, Activity & Attraction Operators Think about OTAs - What to Expect 5 M Your Guide to Working (and Winning) with OTAs - Commissions 9 - Terms & Conditions 12 - Product Setup 13 - Merchandising 17 - Pricing 19 - Guest Reviews 8 M 21 - Analytics 23 37 M Seven Strategic Takeaways (read this if nothing else) 25 Terms & Definitions 28 Page 3 Copyright 2018 Arival LLC All Rights Reserved www.arival.travel ONLINE TRAVEL AGENCIES: AN INTRODUCTION 1. -

Know Your Abcs When Choosing a Tour Operator

KNOW YOUR ABCS WHEN CHOOSING A TOUR OPERATOR Knowing the ABCs of choosing and working with a tour operator will ensure a successful pre-tour, on-tour and post-tour experience for your student group. Six Flags Great America So much to do. So Convenient. Let’s go! For an unforgettable student getaway, head to Lake County, Illinois, just 30 minutes north of Chicago. Experience the thrills on high-flying roller coasters and schedule a performance opportunity at Six Flags Great America. Splash down at the new Great Wolf Lodge Illinois indoor waterpark. Check out the largest outlet and shopping destination in Illinois at Gurnee Mills. Lake County has it all, so close together. Plan your group trip today! Find more group tour ideas and a sample student-themed itinerary at VisitLakeCounty.org/StudentSpaces, and request the free Lake County Visitors Guide by contacting Jayne Nordstrom at (800) 525-3669 or [email protected]. Great Wolf Lodge Illinois Gurnee Mills VisitLakeCounty.org Copyright © 2018 by Premier Travel Media. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, mechanical or electronic, including photocopying and recording, or by any information storage and retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publisher. Requests for permission or further information should be addressed to our offices at: 630-794-0696 Legal Notices While all attempts have been made to verify information provided in this publication, neither the author nor the publisher assumes any responsibility for errors, omissions or contrary interpretation of the subject matter herein. -

Introduction to Hostelling International

Information & Application Form May 2007 INTRODUCTION TO HOSTELLING INTERNATIONAL The Youth Hostel movement was founded in Germany in the early years of this century, and spread rapidly between the wars, especially in Europe. Today, Hostelling International offers you a choice of nearly 4,500 accommodation centres in more than 60 countries worldwide. In Malaysia, the Malaysian Youth Hostels Association - MYHA was formed in the early fifties. The MYHA offers two accommodation centres in Malaysia at Kuala Lumpur & Penang which are associate hostels. Kuala Lumpur: Wira Hotel (Associate Youth Hostel) 123, Jalan Thamboosamy off Jalan Putra 5035 Kuala Lumpur. Tel: 03-4042 3333 Penang: Naza Hostel (Associate Youth Hostel) 555, Jalan CM Hashim Tanjung Tokong 11200 Penang Tel: 04-8909300 NO AGE LIMIT Despite their name, hostels are open to people of all ages in virtually every country where they are located. Only a small number of hostels in Germany have an age restriction which is a requirement of the local legislation. Guests under 14 years of age should be accompanied by an adult. MEMBERSHIP To stay at a hostel, you MUST become a member of your National Youth Hostel Association (YHA). In Malaysia, you can become a member of the MYHA in order to access to the hostels all over the world at an affordable price. PRIVILEGES OF BEING A MEMBER OF THE YHA You can stay at any one of the 4500 hostels worldwide at an affordable price now that you are a member of the YHA. You also get the privilege to certain benefits including access to discounts worldwide. -

World Tourism Organization

Asamblea General A/22/10(III)(k) Vigésima segunda reunión Madrid, 14 de julio de 2017 Chengdu (China), 11-16 de septiembre de 2017 Original: inglés Punto 10 III) k) del orden del día provisional Informe del Secretario General Parte III: Asuntos administrativos y estatutarios k) Acuerdos alcanzados por la Organización I. Introducción 1. El artículo 12 de los Estatutos de la OMT, en relación con los acuerdos suscritos por la Organización, prevé lo siguiente: «La Asamblea podrá examinar toda cuestión y formular toda recomendación sobre cualquier tema que entre en el marco de competencia de la Organización. Además de las que por otra parte le han sido conferidas en los presentes Estatutos, sus atribuciones serán las siguientes: ... l) aprobar o delegar los poderes con vistas a aprobar la conclusión de acuerdos con los gobiernos y las organizaciones internacionales; m) aprobar o delegar los poderes con vistas a aprobar la conclusión de acuerdos con organismos o entidades privadas; …». 2. En virtud de estas disposiciones, se presentan a la Asamblea General los siguientes acuerdos y pactos de trabajo alcanzados con gobiernos, organizaciones intergubernamentales y entidades no gubernamentales. En la Secretaría se pueden consultar todos los acuerdos alcanzados por la Organización. II. Actuaciones propuestas a la Asamblea General 3. Se invita a la Asamblea General a que: a) Tome nota del informe del Secretario General sobre los acuerdos y pactos de trabajo Se ruega reciclar Organización Mundial del Turismo (UNWTO) – Organismo especializado de las Naciones Unidas Capitán Haya 42, 28020 Madrid (España) Tel.: (34) 91 567 81 00 / Fax: (34) 91 571 37 33 – [email protected] / unwto.org A/22/10(III)(k) concluidos, conforme al artículo 12 de los Estatutos, con Gobiernos, organizaciones intergubernamentales y organizaciones no gubernamentales; y b) Apruebe los acuerdos enumerados en el anexo. -

Product Packaging

HISTORY OF PRODUCT PACKAGE TOURS Since their establishment in the 1960's, package tours and the number of receptive tour operators have steadily grown in importance to all aspects of Canadian tourism. It is commonly perceived as a growth opportunity for both travel volume and type of tour package offered. A number of factors contributed to the popularity of packaged tours but the single largest factor was the airlines participation in creating packages to promote their inventory of seats. This not only widened travel options and destinations but also increased the number of travelers. Package tours have several key advantages for the northern traveler including discounted rates for transportation and accommodation, convenience of one-time payment for all or most travel services, ease of vacation planning, and more travel opportunities. THE PRINCIPLES OF PRODUCT PACKAGE DEVELOPMENT Tourists do not visit Toronto just to stay at the Royal York Hotel or travel to Vancouver to visit the Aquarium. Visitors are attracted for a number of widely diverse reasons: • History • Culture • Scenic Splendor (Spectacular) • Unique and different destination They are drawn to a destination because of what they have seen, read, or heard, about an area's attractions. Today most people learn about a destination through the media: • Newspaper • Magazines • Television • Internet/web Travel patterns evolve from this point and invariably centre on the individual's interest in a particular area but seldom on one specific service element. It is here that the convenience and organized structure of a complete travel program becomes the reason for making the choice of destinations. These arrangements can come in a varied assortment of components known as PACKAGE TOURS. -

Working with Inbound Tour Operators

INTERNATIONAL WORKING WITH INBOUND TOUR OPERATORS WHAT IS AN INBOUND TOUR OPERATOR? An inbound tour operator (ITO) is an Australian based business that provides itinerary planning, product selection and coordinates the reservation, confirmation and payment of travel arrangements on behalf of their overseas clients such as wholesaler or retail travel agents. They bring components such as accommodation, tours, transport and meals together to create a fully inclusive itinerary. ITOs are also known as ground operators or destination management companies (DMCs). WHAT DO ITOs DO? The ITO’s role as the local product expert in Australia is to select and agree to work with export ready products. These products are then promoted via overseas travel distributors that sell them, such as wholesalers, direct sellers, travel agents, meeting planners and incentive houses. ITOs choose to work with products that will appeal to the customers that their overseas clients are selling to. They do not work in isolation when selecting suitable product to work with, but are influenced by the needs of their partners overseas. WHAT IS IMPORTANT TO AN ITO? ITOs are looking for: • A tried and tested product that has preferably been operating in the domestic market for a minimum of one to two years with success and fills a need in the markets being targeted • A product that represents good value for money, particularly in markets where the Australian Dollar is strong • A good quality product that is delivered with consistency and excellent customer service • A product that offers the customer a unique experience (so it’s important to know your unique selling point) • Regular availability. -

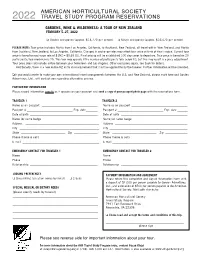

Reservation Form

AMERICAN HORTICULTURAL SOCIETY 2022 TRAVEL STUDY PROGRAM RESERVATIONS GARDENS, WINE & WILDERNESS: A TOUR OF NEW ZEALAND FEBRUARY 5–27, 2022 o Double occupancy (approx. $13,770 per person) o Single occupancy (approx. $16,470 per person) PLEASE NOTE: Tour price includes flights from Los Angeles, California, to Auckland, New Zealand, all travel within New Zealand, and flights from Auckland, New Zealand, to Los Angeles, California. Changes in exchange rates may affect tour price at time of final invoice. Current tour price is based on exchange rate of $1NZ = $0.65 US. Final pricing will be established 100 days prior to departure. Tour price is based on 20 participants; tour maximum is 25. This tour may operate if the number of participants falls below 20, but this may result in a price adjustment. Tour price does not include airfare between your hometown and Los Angeles. Other exclusions apply, see back for details. Additionally, there is a new online NZ entry visa requirement that must be applied for by the traveler. Further information will be provided. o If you would prefer to make your own international travel arrangements between the U.S. and New Zealand, please mark here and Garden Adventures, Ltd., will contact you regarding alternative pricing. PARTICIPANT INFORMATION Please record information exactly as it appears on your passport and send a copy of your passport photo page with the reservations form. TRAVELER 1 TRAVELER 2 Name as on passport ______________________________________ Name as on passport ______________________________________